Extreme Office Makeover: The O Magazine Edition

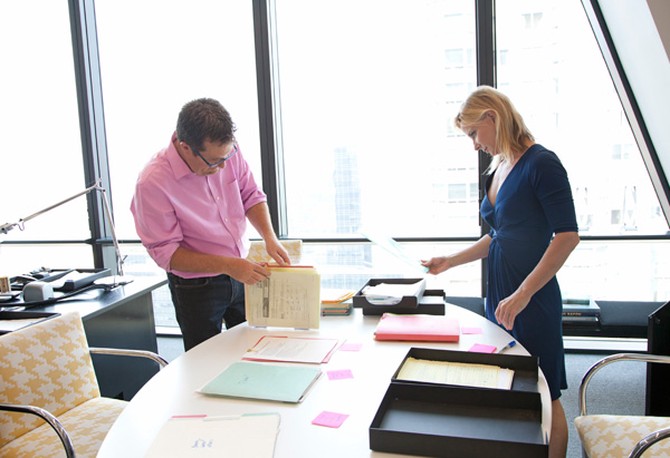

Master organizer Peter Walsh takes on the tsunami of books, gifts, food, and—yes—Betamax tapes threatening to engulf O magazine.

By Meredith Bryan

Photo: Jessica Antola

On his show Enough Already! on OWN, organizing genius Peter Walsh regularly confronts hoarders with bizarre psychological attachments to the junk ransacking their homes. But he's never seen anything like the O staff's stubborn devotion to...well, O. We keep entire libraries of back issues at our desks; we stuff them in every available closet; we stack them in boxes on the floor. Deep down, most of us probably know we'll never be seized by an urgent need to reread that eight-step guide to getting dumped we published in June 2001 (step 6: "If at all possible, get yourself to a small Himalayan Buddhist kingdom"). But we put our collective heart and soul into crafting this magazine. And when it comes to parting ways, we have (as deputy editor Lucy Kaylin says) "emotional baggage."

Walsh calls it something else: "Unhealthy." And so, after trying unsuccessfully to move the mountains of printed matter ourselves, we've summoned him to New York to help us organize our workspace and increase our productivity (okay, fine, we were cited for safety infractions during our last building inspection). He immediately concludes that our excess magazines contribute to a general sense of claustrophobia and helplessness. "Every time I walk in here," he quips, "I feel like I'm drowning."

Of course, he's not talking about just our back-issue issues. Our airy expanse of cubicles is weighed down by papers, stuffed animals, dead orchids, piles of unopened mail, jars of hand cream, yoga DVDs, novels, half-eaten rice cakes, wilted birthday balloons, and framed photos of Oprah and Michael Jackson from the '90s. Yes, we at O, who traffic in insight and enlightenment, who have published a special "De-Clutter Your Life!" issue for the past two years, are in the grips of a mass material psychosis.

"I can help you enormously," Walsh says, his face betraying both pity and weariness. "But there's going to be a bit of pain."

Walsh calls it something else: "Unhealthy." And so, after trying unsuccessfully to move the mountains of printed matter ourselves, we've summoned him to New York to help us organize our workspace and increase our productivity (okay, fine, we were cited for safety infractions during our last building inspection). He immediately concludes that our excess magazines contribute to a general sense of claustrophobia and helplessness. "Every time I walk in here," he quips, "I feel like I'm drowning."

Of course, he's not talking about just our back-issue issues. Our airy expanse of cubicles is weighed down by papers, stuffed animals, dead orchids, piles of unopened mail, jars of hand cream, yoga DVDs, novels, half-eaten rice cakes, wilted birthday balloons, and framed photos of Oprah and Michael Jackson from the '90s. Yes, we at O, who traffic in insight and enlightenment, who have published a special "De-Clutter Your Life!" issue for the past two years, are in the grips of a mass material psychosis.

"I can help you enormously," Walsh says, his face betraying both pity and weariness. "But there's going to be a bit of pain."

Photo: Jessica Antola

"A Purgatory of Stuff"

In some ways, O is like any office. We have our neatniks, like copy director Stephanie Makrias, whose cabinets are bare save for "terrorism sneakers" she'll use to sprint out of Manhattan in a pinch, and our pack rats, like assistant managing editor Ryan Purdy, who rarely meets a free book he doesn't wish to stash at his desk, er, read. But there is one problem at O that transcends any individual: our office giveaway table. Located treacherously close to the coffee machine, this bounty of self-help tomes, olive oils, doggie outfits, BPA-free water bottles, biscotti, shapewear, plastic martini glasses, flip-flops, and organic cleaning products is replenished daily with items left over from photo shoots or sent by helpful publicists. Most of us graze constantly on these freebies, vaguely intending to take them home—a set of Tupperware, maybe an orange pen we featured in "The O List." But the stuff we don't want, we feel bad throwing away. So it piles up until we have a situation not unlike the one outside editor at large Gayle King's office, where an accumulation of granola bars, decorative pillows, self-published memoirs, and gifts from readers—homemade coffee cakes; framed charcoal sketches of Oprah; rag, felt, and yarn dolls in Oprah's likeness—threaten at any moment to bury her assistant.

The prevailing office attitude toward all this clutter can best be approximated as: "We're too busy working on Very Important Things to notice that no one has seen the top of the communal banks of filing cabinets since 2006."

But to Walsh, a clean, organized office is about more than aesthetics. "It's like approaching a blank canvas every morning," he explains. "It fosters creativity." A messy space, on the other hand, makes you feel overwhelmed before you even start working. It also projects the wrong message, Walsh says: "You want your office to say to writers and advertisers, These people are in command of their area. They know what they're doing." Instead of, These people have a thing for cupcakes and books about the spiritual side of weight loss.

Walsh asks editor in chief Susan Casey—whose office is stocked with Ethiopian coffee beans, coconut water, bottles of wine, plush pink bathrobes, a Christmas gift she never got around to sending to her brother in Canada, and four different umbrellas—why she doesn't just take the excess stuff home, where it won't obstruct her desk and keep her from finding important documents. "I guess the question is, do I want all this stuff in my apartment?" Casey says. "And the answer is probably no. So it's a purgatory of stuff. A purgatory of well-intentioned stuff."

"Decision to Keep"

We begin the way Walsh starts all his projects: with a purge. He says our problem is not the incoming volume of stuff; it's that we delay making decisions about what to do with it. That's why today, everything that serves no essential work purpose will be emptied into the aisles between cubicles to be donated or packed into Dumpsters; items we want to keep that do not help us do our jobs will be placed in bags to be taken home. "You can keep whatever you want," Walsh assures us. "But make a decision to keep. The minute you say, 'I'll deal with it later,' the battle is lost." Soon the hall is filling with cans of Red Bull, mouse pads, mojito mix, an avocado slicer, multiple copies of The Kite Runner. "Keep walking!" Walsh barks when passersby gaze greedily at the castoffs.

The prevailing office attitude toward all this clutter can best be approximated as: "We're too busy working on Very Important Things to notice that no one has seen the top of the communal banks of filing cabinets since 2006."

But to Walsh, a clean, organized office is about more than aesthetics. "It's like approaching a blank canvas every morning," he explains. "It fosters creativity." A messy space, on the other hand, makes you feel overwhelmed before you even start working. It also projects the wrong message, Walsh says: "You want your office to say to writers and advertisers, These people are in command of their area. They know what they're doing." Instead of, These people have a thing for cupcakes and books about the spiritual side of weight loss.

Walsh asks editor in chief Susan Casey—whose office is stocked with Ethiopian coffee beans, coconut water, bottles of wine, plush pink bathrobes, a Christmas gift she never got around to sending to her brother in Canada, and four different umbrellas—why she doesn't just take the excess stuff home, where it won't obstruct her desk and keep her from finding important documents. "I guess the question is, do I want all this stuff in my apartment?" Casey says. "And the answer is probably no. So it's a purgatory of stuff. A purgatory of well-intentioned stuff."

"Decision to Keep"

We begin the way Walsh starts all his projects: with a purge. He says our problem is not the incoming volume of stuff; it's that we delay making decisions about what to do with it. That's why today, everything that serves no essential work purpose will be emptied into the aisles between cubicles to be donated or packed into Dumpsters; items we want to keep that do not help us do our jobs will be placed in bags to be taken home. "You can keep whatever you want," Walsh assures us. "But make a decision to keep. The minute you say, 'I'll deal with it later,' the battle is lost." Soon the hall is filling with cans of Red Bull, mouse pads, mojito mix, an avocado slicer, multiple copies of The Kite Runner. "Keep walking!" Walsh barks when passersby gaze greedily at the castoffs.

Photo: Jessica Antola

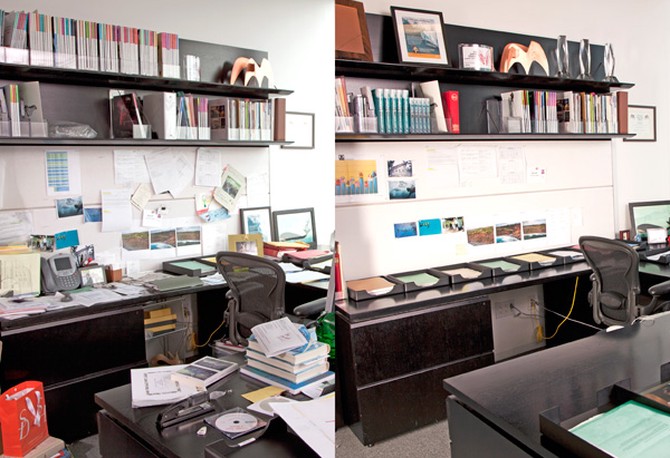

Once we've cleared our desks, the floor, and the communal storage spaces around the office, Walsh asks us to set limits for the future: Everyone gets one file drawer for personal belongings (currently, an average bank of filing cabinets contains one drawer for files and ten for shoes, packaged snacks, and old cell phone chargers). When our drawer no longer closes, we must remove something before adding new items.

Certain high-volume objects get a "system." Take King's books. She receives dozens every month, most sent by people hoping to appear on her show on OWN. Editorial assistant Arianna Davis stacks the books on one of the aforementioned communal filing cabinets, where they remain in perpetuity, claiming more and more surface area, even though King will never open many of them. Meanwhile, five feet away, a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf is being used to display framed photos of everyone Oprah has ever interviewed for the magazine. Walsh asks a simple question: Why not move the books to the bookshelf?

At this, everyone looks confused. Our editorial business coordinator, Kori Scott, suggests that Walsh ask Kaylin for permission to relocate the photos; Kaylin directs Walsh to Casey; Casey, recalling that Oprah herself gave the pictures to King as a gift, refers him to Davis; Davis e-mails King, who is in Chicago.

King's speedy yes bolsters everyone—hooray for small victories!—and Walsh stakes out space for the photos on an empty stretch of white wall. As he helps transfer King's books to their new shelves, he explains that Davis will be in charge of quantity control: Each week's arrivals will get their own shelf, until all five are full. Then the five-week-old books will be donated in order to make room for the current week's stock, and so on.

The interns, meanwhile, are tackling the largest task of all: the row of tall cabinets stuffed with old O's. After several huddled discussions and a few phone calls to various company executives, we've reluctantly agreed to part with all but ten copies of each back issue. This will clear up space for the food department's library of cookbooks, currently monopolizing the bookshelf in the books department and leaving the books editors with no shelves at all.

As he gleefully flings issues from 2001 into a Dumpster, Walsh lets out a muffled shriek. He's stumbled upon a long-forgotten stash of VHS and Betamax tapes. "It's like gazing into 1985!" he gasps, looking genuinely stricken. Several people actually blush. We work at a modern media company, after all; we publish an iPad app and live-tweet our workdays. Still, no one will authorize the disposal of the tapes. It's becoming clear that a peculiar power vacuum is part of our problem. Since no one is in charge of keeping order, no one feels qualified to make decisions. Everyone is relieved when Davis finally thinks to call the former editor in chief's former assistant, who grants permission to throw the tapes away.

Certain high-volume objects get a "system." Take King's books. She receives dozens every month, most sent by people hoping to appear on her show on OWN. Editorial assistant Arianna Davis stacks the books on one of the aforementioned communal filing cabinets, where they remain in perpetuity, claiming more and more surface area, even though King will never open many of them. Meanwhile, five feet away, a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf is being used to display framed photos of everyone Oprah has ever interviewed for the magazine. Walsh asks a simple question: Why not move the books to the bookshelf?

At this, everyone looks confused. Our editorial business coordinator, Kori Scott, suggests that Walsh ask Kaylin for permission to relocate the photos; Kaylin directs Walsh to Casey; Casey, recalling that Oprah herself gave the pictures to King as a gift, refers him to Davis; Davis e-mails King, who is in Chicago.

King's speedy yes bolsters everyone—hooray for small victories!—and Walsh stakes out space for the photos on an empty stretch of white wall. As he helps transfer King's books to their new shelves, he explains that Davis will be in charge of quantity control: Each week's arrivals will get their own shelf, until all five are full. Then the five-week-old books will be donated in order to make room for the current week's stock, and so on.

The interns, meanwhile, are tackling the largest task of all: the row of tall cabinets stuffed with old O's. After several huddled discussions and a few phone calls to various company executives, we've reluctantly agreed to part with all but ten copies of each back issue. This will clear up space for the food department's library of cookbooks, currently monopolizing the bookshelf in the books department and leaving the books editors with no shelves at all.

As he gleefully flings issues from 2001 into a Dumpster, Walsh lets out a muffled shriek. He's stumbled upon a long-forgotten stash of VHS and Betamax tapes. "It's like gazing into 1985!" he gasps, looking genuinely stricken. Several people actually blush. We work at a modern media company, after all; we publish an iPad app and live-tweet our workdays. Still, no one will authorize the disposal of the tapes. It's becoming clear that a peculiar power vacuum is part of our problem. Since no one is in charge of keeping order, no one feels qualified to make decisions. Everyone is relieved when Davis finally thinks to call the former editor in chief's former assistant, who grants permission to throw the tapes away.

Photo: Jessica Antola

Walsh shares his flat-surfaces principle with editor in chief Susan Casey. "You have to keep these surfaces clear, because they're work spaces, not storage space," he says. Together they organize Casey's office by storing like with like—contracts go with other contracts, story drafts stay with others from the same month.

Photo: Jessica Antola

Casey initially told Walsh she was "beyond help," but by now she's purged her office of Post-its, file folders, therapeutic travel pillows, excess copies of her recent best-selling book, The Wave, and a salt shaker in the shape of a shark fin. Her space feels bright and crisp. Walsh empowers Karla Gonzalez, Casey's assistant, to "manage upward," carving out five minutes at the end of each day to help Casey clear surface areas and pack up anything she wants to take home. (When other assistants see clutter building near their areas, they, too, are instructed to ask for permission to throw it away—or better yet, just throw it away.)

A few days after Walsh returns to California, a new calm has set in. "It's amazing," says Casey. "By de-cluttering and organizing, it's like you open up an energetic space to get things done. I got so excited that I went home and cleaned my apartment, too."

A few days after Walsh returns to California, a new calm has set in. "It's amazing," says Casey. "By de-cluttering and organizing, it's like you open up an energetic space to get things done. I got so excited that I went home and cleaned my apartment, too."

Published 08/16/2011