Are You Ready for a Birth Control Makeover?

Even if you've been using the same method for a decade (make that especially if), it may be time to reassess your options.

By Corrie Pikul

Photo: Thinkstock

Finding the right birth control can be like finding the right hairstyle: Once we've got one that works, we tend to stick with it—even when there might be something else out there that's better. Maybe you're in a different relationship situation now, or you've grown weary of popping a pill every day or putting in a ring every month. Or perhaps you've heard news reports that concerned you or stories from friends that intrigued you. While there aren't many brand new options on the market, some of the old classics have been recently updated. This slideshow, with information about the most popular forms of birth control in the United States, can help you decide if you're ready for a change.

Photo: Thinkstock

Condoms

What: Drugstores now offer as many options and flavors as a Baskin-Robbins. We all scream for Tropical Premiums!

Failure rate*: 2–18%

Who: Single women who are as concerned about getting sexually transmitted diseases as about getting pregnant; women who are looking for no-commitment birth control.

Why:

*Failure rate: the percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of perfect use and the first year of typical use of contraception.

Source: Contraceptive Failure in the United States by James Trussell at the Office of Population Research, 2011 (provided by Planned Parenthood)

Failure rate*: 2–18%

Who: Single women who are as concerned about getting sexually transmitted diseases as about getting pregnant; women who are looking for no-commitment birth control.

Why:

- Latex rubber condoms are the best line of defense (besides abstinence) against STDs for which there is no known cure, like herpes, HPV and HIV.

- They allow for spontaneity, they're discreet, and they're relatively cheap. Value packs cost just $25 for 36 condoms—three of those would be more than enough to accommodate the average woman's yearly sexual activity.

- They absolutely require a man's cooperation. But the new generation may be more receptive: The CDC just reported that use of condoms by male teens is on the rise.

- An allergic reaction to latex can cause severe reactions, so women with this issue should look for polyurethane plastic. However, latex allergies only affect about six in 100 women (interestingly, they may also have a sensitivity toward bananas, avocados and kiwi fruit, which share similar proteins). More often, it's the spermicide that's causing vaginal irritation, says Daniela Carusi, MD, the director of general gynecology at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. As an alternative for the irritation-prone, Carusi suggests spermicide-free condoms with a water-based lubricant like K-Y Brand Jelly.

*Failure rate: the percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of perfect use and the first year of typical use of contraception.

Source: Contraceptive Failure in the United States by James Trussell at the Office of Population Research, 2011 (provided by Planned Parenthood)

Photo: Thinkstock

The Sponge

What: Remember the Seinfeld episode where Elaine freaked out when she heard her beloved Today Sponge was going off the market? She'd be happy to know that it has recently returned. It's still the same product since 1983 but with new blue packaging that looks more sea sponge than dishwashing sponge.

Failure rate*: It is 9 to 12 percent for those who have never given birth and 20 to 24 percent for those who have. The drop in effectiveness for mothers isn't completely understood, says David Mayer, founder of Mayer Laboratories (the makers of the Today Sponge), but the theory is that giving birth can stretch the opening between the vaginal canal and the uterus, possibly compromising the fit of the sponge. Mayer adds that a large international clinical study (posted on the product website) showed lower rates of pregnancy for women who have had children—equal to the rate for women with no children.

Who: Younger women who have never been pregnant and who are comfortable enough with their anatomy to make sure the sponge fully covers the cervix; couples looking for a "next step" birth control after condoms; women who are uncertain about hormonal contraceptives.

Why:

Failure rate*: It is 9 to 12 percent for those who have never given birth and 20 to 24 percent for those who have. The drop in effectiveness for mothers isn't completely understood, says David Mayer, founder of Mayer Laboratories (the makers of the Today Sponge), but the theory is that giving birth can stretch the opening between the vaginal canal and the uterus, possibly compromising the fit of the sponge. Mayer adds that a large international clinical study (posted on the product website) showed lower rates of pregnancy for women who have had children—equal to the rate for women with no children.

Who: Younger women who have never been pregnant and who are comfortable enough with their anatomy to make sure the sponge fully covers the cervix; couples looking for a "next step" birth control after condoms; women who are uncertain about hormonal contraceptives.

Why:

- It can be inserted up to 24 hours before having sex.

- Once it's in place, it's working, and it can't be felt by a woman or her partner.

- It's safe for most women, with almost no side effects.

- When used with condoms, it provides extra reassurance.

- The effectiveness data isn't as reassuring as other methods.

- It needs to remain in place for at least six hours after sex.

- Insertion and removal take practice.

Photo: Thinkstock

The Diaphragm

What: This low-tech invention still works the same way that it did when reproductive rights activist Margaret Sanger introduced it to the United States in 1916: A small silicone dome that looks like a kitchen spice cup is filled with spermicide and manually inserted into the vagina to cover the cervix. This prevents sperm from meeting up with an egg.

Failure rate*: 6–12%

Who: CDC data shows that the diaphragm has virtually disappeared from the purses and nightstands of American women. Carusi says that she rarely sees patients who still use it, and those who do are somewhat older and tend to have issues with hormonal birth control or with condoms. Other potential users include fans of vintage clothing and midcentury feminist novels, like The Group by Mary McCarthy.

Why:

Failure rate*: 6–12%

Who: CDC data shows that the diaphragm has virtually disappeared from the purses and nightstands of American women. Carusi says that she rarely sees patients who still use it, and those who do are somewhat older and tend to have issues with hormonal birth control or with condoms. Other potential users include fans of vintage clothing and midcentury feminist novels, like The Group by Mary McCarthy.

Why:

- It's a barrier method that women can control.

- When used with condoms, it provides extra reassurance to those who really don't want to get pregnant.

- It's hormone free.

- The spermicidal gel can be messy and awkward.

- The diaphragm requires regular cleaning and care—kind of like dentures. This can make women feel mature, but in a grown-up kind of way, not an X-rated "adult" kind of way.

- Use of these devices has been linked to an increased risk of bladder infections, says Carusi.

- Current models need to be fitted to the cervix by a doctor. However, like swing coats, pumps and other Mad Men era accessories, the diaphragm may be ready for a refresh. Seattle-based health nonprofit called PATH has been working on a sleeker, user-friendly, one-size-fits-most diaphragm (no fitting necessary) in a splashy purple color. They plan to submit an application for the SILCS diaphragm to the FDA next year. This product could be available in the U.S. within the next couple of years.

Photo: Thinkstock

The Pill

What: A big CDC survey issued last year found that the pill is the most popular form of birth control in America (used by 28 percent of women using contraception). The most common types of pills contain two hormones: estrogen and progestin (a synthetic form of progesterone), which together prevent the ovaries from releasing eggs, thicken the cervical mucus to keep sperm from joining with an egg and thin the uterine lining so that a fertilized egg would have trouble attaching.

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: Women who are more concerned with avoiding pregnancy than getting an STD; younger women who don't have kids; women who are committed to habits like flossing.

Why:

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: Women who are more concerned with avoiding pregnancy than getting an STD; younger women who don't have kids; women who are committed to habits like flossing.

Why:

- They help regulate periods. (By the way, women on the pill don't release an egg a month like they normally would; the "period" is actually a withdrawal bleed in response to fluctuating hormone levels.)

- Carusi says the pill can clear up acne, help with heavy periods (as well as side effects like cramping), forestall bone thinning and protect against endometrial, uterine and ovarian cancers as well as serious infection in the ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus. The pill is sometimes prescribed to women who carry a gene for ovarian cancer, Carusi says, because ovaries that aren't ovulating are less prone to this disease (unfortunately, this doesn't mean that the pill stops the ovaries from aging).

- They require a major commitment. The website Bedsider also offers a free reminder service where they'll send a daily text or email letting you know it's time to take your pill.

- Your gynecologist can help you find a hormone level that works for you. The problem is that this trial-and-error phase can involve estrogen-related glitches like irregular and breakthrough bleeding, a flagging sex drive (due to a decrease in the amount of testosterone released by the ovaries) and brown splotches on the face.

- Many women are concerned about gaining weight, but Carusi says this is relatively uncommon and that early studies showing a correlation between the pill and extra pounds involved college students whose gains were likely due to the "freshman 15."

- It's a myth that you need to "flush the pill out of your system" before trying to conceive. The estrogen and progestin are gone within a few days. However, it's not uncommon for a woman's natural hormone levels to take two or three months to adjust to normal, which can make it tricky to predict ovulation (and therefore, to time a pregnancy).

- It's important to be aware that all contraceptives that contain estrogen—the pill, the ring, the patch, the shot—can increase the risk of blood clots, heart attacks and strokes, and they can be dangerous for women with certain risk factors (check with your doctor). Studies have reported an even greater risk for pills containing a variation of progestin called drospirenone, including Yaz and Yasmin. The FDA is currently examining this link. "I tell patients interested in Yasmin that the blood clot risk may be doubled from about three in 10,000 to six in 10,000," says Carusi. "Many women are still comfortable with this."

- Progestin-only pills, or minipills, don't have any estrogen at all. These need to be taken at the same time each day, making them an unrealistic option for those who can't stick to a routine. They also tend to cause more spotting than combo pills.

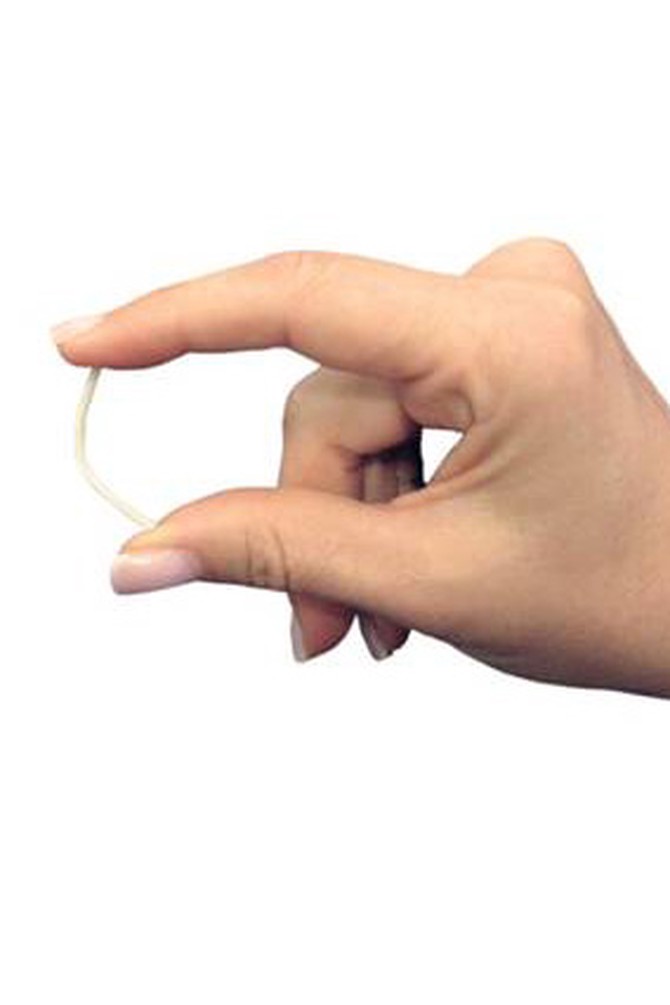

Photo: Merck

The Ring

What: The NuvaRing is a flexible, transparent ring that is inserted into the vagina once a month, where it releases a low dose of estrogen and progestin. To get a sense of how big it is, touch your pointer finger to your thumb to make the "okay" sign.

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: Women who are happy with the pill but have trouble remembering to take it every day.

Why:

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: Women who are happy with the pill but have trouble remembering to take it every day.

Why:

- After it's inserted, women can forget about it for the next three weeks.

- The lower dose of estrogen means that side effects (like facial hyperpigmentation) tend to be less noticeable.

- Some women find that the ring also makes their periods shorter and lighter.

- As noted on the NuvaRing inserts, cardiovascular risks may be higher with the ring than with some pills—especially for smokers and women over 35.

- Carusi says that a lot of younger women are uncomfortable about getting personal with their vaginas, and the ring involves hands-on attention. Long fingernails can be a liability.

- It occasionally makes its presence known during sex—and sometimes even slips out. To remain effective, it then needs to be rinsed with lukewarm water and reinserted within three hours.

- "Many women think it's too expensive," says Carusi (co-pays vary, but the average cost is $34). Unlike the pill, the NuvaRing isn't available in a discounted generic version.

Photo: Thinkstock

The Shot (Depo-Provera)

What: One injection of progestin into the upper arm, administered in a doctor's office, is effective at preventing pregnancy for three months.

Failure rate*: 0.2–6%

Who: Women who can never remember to take their pill; women who don't plan to get pregnant in the near future.

Why:

Failure rate*: 0.2–6%

Who: Women who can never remember to take their pill; women who don't plan to get pregnant in the near future.

Why:

- One quick pinch means women don't need to worry about pregnancy or periods for three months.

- No estrogen means no estrogen-related complications.

- It can be an effective treatment for pelvic pain caused by intense periods or endometriosis, says Carusi.

- It's not a reliable long-term plan because it can deplete calcium stored in the bones, and the manufacturer warns against using the shot for longer than two years. Carusi says that her office counsels teens, whose bones are still forming, and perimenopausal women, whose bones may be weakening, to consider other methods after a year or two.

- Some women don't do shots, period.

- Weight gain is common.

- If you happen to experience negative side effects, like hair loss, depression, or a change in sex drive, appetite or weight, you'll have to deal with them for 12 to 14 weeks until the shot wears off.

- It can take months to a year for a woman to become pregnant after stopping the medication, Carusi says.

Photo: Ortho Evra

The Patch (Ortho Evra)

What: Every week for three weeks, you stick a plastic, Band-Aid-like patch on your skin, and it emits estrogen and progestin through your skin and into your bloodstream. After the third week, you go patchless for a week and then slap on a new one.

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: "It's mostly for women who won't use anything else, as some birth control is better than nothing," says Carusi. "We don't prescribe it that often."

Why:

Failure rate*: 0.3–9%

Who: "It's mostly for women who won't use anything else, as some birth control is better than nothing," says Carusi. "We don't prescribe it that often."

Why:

- It's doesn't involve needles.

- You don't need to stick anything inside you.

- You can choose where to put it (back, lower abdomen, upper arm, etc.).

- Because hormones enter the blood directly and are processed by the body differently than hormones in the pill, women on the patch are exposed to about 60 percent more estrogen. This raises their risk of estrogen-related side effects (including everything from a dampened sex drive to a dangerous blood clot).

- Excessive sweating can cause the patch to fall off.

- If you forget to change the patch on time, the next-step instructions can be confusing and may require you to use a backup form of contraception.

- The near-constant presence of the patch can irritate the skin.

- The patch is not recommended for women who weigh more than 198 pounds, or smokers over the age of 35.

Photo: Thinkstock

The Intrauterine Device (IUD)

What: An IUD is a tiny T-shaped device that is implanted into the uterus by a doctor. It has a cord dangling down into the upper part of the vagina and remains in the uterus for five to 10 years, when it is time to remove it and insert a new one. IUDs work by creating a uterine environment that is inhospitable to sperm, and one type also secretes progestin as a backup. These devices were horribly maligned after the Dalkon Shield medical debacle of the '70s (rightfully so) but now seem poised to make a comeback. Manufacturers say that flaws in the design and procedure that made old IUDs so dangerous for women (like the Shield's woven double strands that transmitted dangerous bacteria) have been fixed, and the CDC has approved IUDs as safe for women at low risk for STDs. Among reproductive researchers and healthcare providers, at least, the IUD has become the new "it" contraceptive. The percent of women on birth control who favor the IUD has increased to 5.5 percent from 1.3 percent in 1995, and Carusi says that she and her colleagues have seen a big uptick in the number of Boston users in the past few years. There are two types of IUDs currently available in the United States:

Who: Currently most popular with women with at least one child, it has started catching on with women without kids. The CDC acknowledges that while "well-conducted studies" show no increased risk to fertility, there is some conflict over the data—despite that, IUDs are CDC-approved for women with children as well as those without.

Why:

- The ParaGard is made of copper. It's been around since 1984 and doesn't contain hormones but has been known to cause heavy periods, breakthrough bleeding and uncomfortable cramps. It can be left in the uterus for up to 10 years.

ParaGard failure rate: 0.6–0.8% - The Mirena is made of plastic and contains a progestin hormone called levonorgestrel that is often used in birth control pills. It's estrogen free, and can be safely left in the uterus for up to five years. This type of IUD, which the FDA approved as a contraceptive in 2000 and as a treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding in 2009, is more commonly chosen by women.

Mirena failure rate: 0.2%

Who: Currently most popular with women with at least one child, it has started catching on with women without kids. The CDC acknowledges that while "well-conducted studies" show no increased risk to fertility, there is some conflict over the data—despite that, IUDs are CDC-approved for women with children as well as those without.

Why:

- It doesn't require another thought for at least half a decade.

- It's more reliable than birth control pills.

- There's no estrogen involved.

- When it's inserted correctly, women can't feel it—nor can their partners.

- It can be inserted as early as six weeks after a woman gives birth and is then safe for use during breastfeeding.

- It's reversible.

- The cost for the IUD and the insertion ranges from $500 to $1,000. While affordable when amortized over the life span of the device, it's a lot to pay up front. The cost barrier should disappear in 2013 when insurance plans will be required to cover FDA-approved contraception.

- The insertion doesn't tickle; Carusi describes it as a "visceral, internal pain" (usually less intense for women whose cervixes have been stretched by giving birth). One writer described it as "a spasm unlike any cramp...like something deep inside me being twisted up and wrung out." The procedure only lasts a few minutes, and Carusi said the pain goes away as soon as it's over, but some women experience lingering cramps for a few days.

- While IUDs alone haven't been proven to cause infertility, catching an STD like chlamydia or gonorrhea while using an IUD is extremely dangerous and can cause infections that result in infertility. Because of this risk, many single women opt to double-up protection with a condom.

- Researchers will admit that they don't know exactly why the insertion of this device in the uterus why it works so well as a contraceptive, even without hormones.

- IUDs have a scary history, and for some women, that history involved their moms and aunts.

Photo: Merck

The Implant (Implanon)

What: Approved by the FDA in 2006, this is a matchstick-size rod that is implanted by a doctor under the skin of the upper arm, where it releases a low dose of progestin (etonogestrel). It stays in place, invisible but detectable with a little prodding, for up to three years.

Failure rate*: 0.05%

Who: Women who have just given birth and know they won't remember or have time to return to the doctor for an IUD; women who have grown weary of the pill; women who would rather have something implanted in their arm than their uterus.

Why:

Failure rate*: 0.05%

Who: Women who have just given birth and know they won't remember or have time to return to the doctor for an IUD; women who have grown weary of the pill; women who would rather have something implanted in their arm than their uterus.

Why:

- It's impressively effective for three years—which is just slightly longer than the average American family waits to have another baby.

- It's safe to use after giving birth, says Carusi.

- There's nothing to remember.

- The implantation is a minor surgery and must take place in a doctor's office.

- The idea of having a device under their skin makes some women uncomfortable.

- According to the manufacturer, it is unknown if the risk of blood clots with the implant is different than with birth control pills.

- There's not a lot of data on the effectiveness for overweight women.

- Carusi says that some women report irregular, hard-to-predict bleeding.

- A botched insertion or removal, while rare, could lead to serious problems.

- It takes time to get used to. Carusi often advises patients to give it six months to a year.

Published 10/19/2011

As a reminder, always consult your doctor for medical advice and treatment before starting any program.