6 Things Everyone Living With Chronic Pain Should Know

Having dealt with a debilitating chronic illness for two decades, Karen Duffy shares how she's learned to be the boss of her pain.

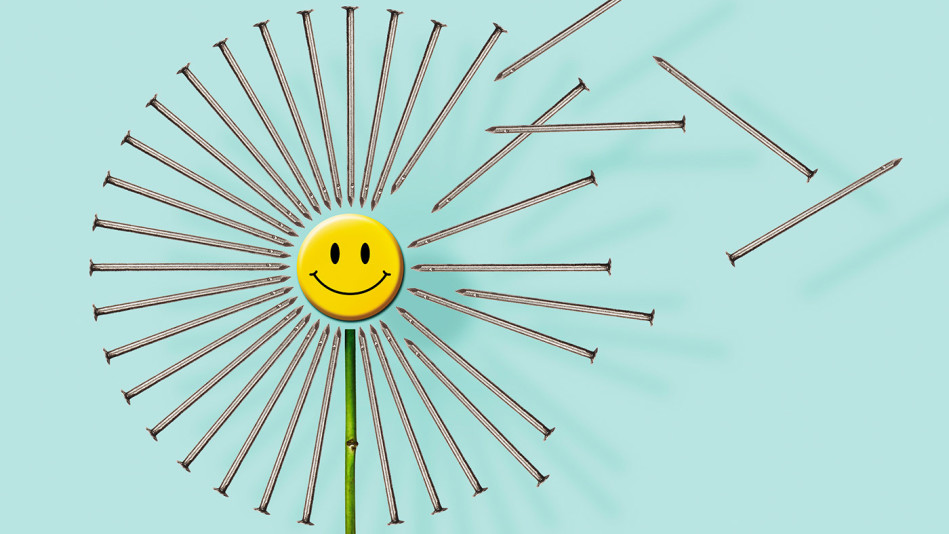

Illustration: Matt Chase

If you came of age in the 1980s or '90s, you watched MTV. And if you watched MTV, you knew about the cool-girl VJ Karen Duffy—or Duff, as everyone still calls her. What you probably don't know is that in 1996, after years of mysterious headaches and bouts of pneumonia, Duffy was diagnosed with sarcoidosis, an incurable disease that caused clusters of inflammatory cells, or granulomas, to grow in her brain, central nervous system, and lungs—resulting in constant pain.

For a while, Duffy muscled through, continuing to model and work on TV. But the discomfort never subsided. Today, before she even opens her eyes in the morning, searing pain fires on the right side of her head and shoots down her neck, shoulder, and spine. A burning sensation radiates from her left elbow, causing her fingers to involuntarily contract, making it difficult for her to grasp items. A few days a week, she hurts too much to leave the house. Still, Duffy, now 55, manages to be an enthusiastic hockey mom to her 14-year-old son; attend charity fundraisers with her husband, John Lambros; and occasionally appear at events to support friends' projects, despite daily "nerve-jangling" pain. Now, in her new book, Backbone: Living with Chronic Pain Without Turning into One, she draws on her experience as a patient and advocate to show—with tips, jokes, illustrations, and thoughtful advice—that chronic illness doesn't have to ruin your life. We asked her to tell us more.

O: How do you handle the frustration of not being able to do all the things you want to do?

KD: There's a lot of shame involved with chronic illness because you worry that people think you're a slacker. I would love to be able to play tennis with my husband and be at every hockey practice with my son, but monkeys will fly out of my butt first. I don't think it's good for my family to see me beat myself up with guilt. Living with pain is a bummer, but it's not all bad. Maybe my son is more independent and compassionate because I don't have the strength in my hands to help him pack his hockey bag, and he's learned to be a great storyteller by remembering funny things to tell me later.

Illustration: Matt Chase

O: Does medication help?

KD: I'm deeply grateful for the strong prescription medications I take daily. I rely on extended-release morphine pills and lidocaine patches on my neck. They don't give me a buzz or cause any mood changes; they just provide some relief. I also periodically take oral steroids, and sometimes I'm given megadoses of steroids through an IV.

O: How do you deal with side effects?

KD: The medicine can be as uncomfortable and complicated as the illness. With steroids, I've experienced chipmunk cheeks, the "buffalo hump" of extra back fat, and facial hair—I was the only Revlon model who could also do an aftershave commercial. I had to learn to love the chub and adapt my wardrobe. I've developed glaucoma that's required multiple surgeries, and I wear special lenses. But I'm thankful for steroids: They help with joint pain and mobility. Neuropathy from chemo made my feet numb, and one year I was stubbing them so hard, I broke the left, the right, then the left again—so I wore a walking boot spray-painted gold to report from red carpets for HBO. I was on methotrexate for my fertile years, so I'd count missing my fertility window as the most difficult side effect of all. I dealt with that one by having my eggs implanted in a surrogate mom—my womb mate—and the result was the handsomest, funniest member of our family.

O: What about alternative therapies?

KD: Reading is my complementary therapy. It helps distract me from discomfort. I can do it in bed, and I can prop up a digital device when my hands are too weak to hold a book. There's nothing I'd rather do than read—which is good, because I can't exactly ski anymore.

O: You write about helping people even when you're barely functional, and after your diagnosis, you trained to become a hospital chaplain. Why is service to others so important to you?

KD: When people hear that I have a chronic illness, they'll say things like "Focus on you." Well, my spiritual and emotional fulfillment is based not on who I am but on what I can give. Plus, many of my favorite philosophers suggested that self-fulfillment is found through service. Who am I to argue with them?

O: After dealing with extreme pain for so long, how do you keep from going to a dark place—and staying there?

KD: When you're juggling a chronic condition and multiple treatments, you learn to expect problems. It's up to me to make the best of things before they go sideways. My son recently told some friends, "It's like I have two mothers: the cavewoman and the one-woman conga line." Maybe I push extra hard to make up for the down days.

For a while, Duffy muscled through, continuing to model and work on TV. But the discomfort never subsided. Today, before she even opens her eyes in the morning, searing pain fires on the right side of her head and shoots down her neck, shoulder, and spine. A burning sensation radiates from her left elbow, causing her fingers to involuntarily contract, making it difficult for her to grasp items. A few days a week, she hurts too much to leave the house. Still, Duffy, now 55, manages to be an enthusiastic hockey mom to her 14-year-old son; attend charity fundraisers with her husband, John Lambros; and occasionally appear at events to support friends' projects, despite daily "nerve-jangling" pain. Now, in her new book, Backbone: Living with Chronic Pain Without Turning into One, she draws on her experience as a patient and advocate to show—with tips, jokes, illustrations, and thoughtful advice—that chronic illness doesn't have to ruin your life. We asked her to tell us more.

O: How do you handle the frustration of not being able to do all the things you want to do?

KD: There's a lot of shame involved with chronic illness because you worry that people think you're a slacker. I would love to be able to play tennis with my husband and be at every hockey practice with my son, but monkeys will fly out of my butt first. I don't think it's good for my family to see me beat myself up with guilt. Living with pain is a bummer, but it's not all bad. Maybe my son is more independent and compassionate because I don't have the strength in my hands to help him pack his hockey bag, and he's learned to be a great storyteller by remembering funny things to tell me later.

Illustration: Matt Chase

O: Does medication help?

KD: I'm deeply grateful for the strong prescription medications I take daily. I rely on extended-release morphine pills and lidocaine patches on my neck. They don't give me a buzz or cause any mood changes; they just provide some relief. I also periodically take oral steroids, and sometimes I'm given megadoses of steroids through an IV.

O: How do you deal with side effects?

KD: The medicine can be as uncomfortable and complicated as the illness. With steroids, I've experienced chipmunk cheeks, the "buffalo hump" of extra back fat, and facial hair—I was the only Revlon model who could also do an aftershave commercial. I had to learn to love the chub and adapt my wardrobe. I've developed glaucoma that's required multiple surgeries, and I wear special lenses. But I'm thankful for steroids: They help with joint pain and mobility. Neuropathy from chemo made my feet numb, and one year I was stubbing them so hard, I broke the left, the right, then the left again—so I wore a walking boot spray-painted gold to report from red carpets for HBO. I was on methotrexate for my fertile years, so I'd count missing my fertility window as the most difficult side effect of all. I dealt with that one by having my eggs implanted in a surrogate mom—my womb mate—and the result was the handsomest, funniest member of our family.

O: What about alternative therapies?

KD: Reading is my complementary therapy. It helps distract me from discomfort. I can do it in bed, and I can prop up a digital device when my hands are too weak to hold a book. There's nothing I'd rather do than read—which is good, because I can't exactly ski anymore.

O: You write about helping people even when you're barely functional, and after your diagnosis, you trained to become a hospital chaplain. Why is service to others so important to you?

KD: When people hear that I have a chronic illness, they'll say things like "Focus on you." Well, my spiritual and emotional fulfillment is based not on who I am but on what I can give. Plus, many of my favorite philosophers suggested that self-fulfillment is found through service. Who am I to argue with them?

O: After dealing with extreme pain for so long, how do you keep from going to a dark place—and staying there?

KD: When you're juggling a chronic condition and multiple treatments, you learn to expect problems. It's up to me to make the best of things before they go sideways. My son recently told some friends, "It's like I have two mothers: the cavewoman and the one-woman conga line." Maybe I push extra hard to make up for the down days.