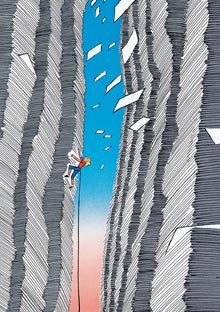

All Work, No Life

A new job fervor is making old-fashioned workaholism look like slacking.

Illustration: Guy Billout

They use their jobs like amphetamines, eagerly clock Herculean hours, and find the career rush far more satisfying than the money they make. According to a recent study in the Harvard Business Review, "extreme" workers are on the rise. Cultural critic Catherine Orenstein calls the phenomenon "the American Dream on steroids."

Extreme jobs, according to the study, meet five of ten criteria: unpredictable flow of work, inordinate scope of responsibility, tight deadlines, work-related events outside regular hours, availability to clients 24/7, accountability for profit/loss, recruiting and mentoring, heavy travel, large number of direct reports, and physical presence at the workplace at least ten hours a day. In the study, 21 percent of high earners had this type of job.

"We're a culture of thrill-seekers, and these people really do see their jobs as an adrenaline-pumping sport," says study coauthor Sylvia Ann Hewlett, PhD, founding president of the Center for Work-Life Policy in New York City. The performance high, however, comes at a price: Fifty-seven percent of the women in the nationwide survey said they didn't want to sustain their current lifestyle for more than a year, and most reported that their jobs were negatively affecting their relationships and health. (Men, who were twice as likely to have the support of a stay-at-home partner, were less worried on most counts.)

What's the hook?

The appeal of such radical workaholism may be part of a vicious cycle. "We've flipped work and life," says Arlie Russell Hochschild, PhD, a professor of sociology at the University of California at Berkeley and author of The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. Because we're pegging longer hours, she maintains, private lives are getting emptier, and, in turn, we're avoiding them; it's easier to go to the office.

Dialing Down

Several experts believe that über-professionals should recalibrate their priorities—in fact, they can approach the task the same way they go for results in their careers. Stew Friedman, PhD, director of the Wharton School Work/Life Integration Project, points out, "To be successful, you don't have to be extreme, but you need to be innovative, experimenting with how to get things done."

Friedman recommends a couple of exercises. Begin by writing a narrative of yourself 15 years from now ("I'm living with my husband in Pasadena, and we've just opened a restaurant..."). Next, jot down these four categories: work, home/family, community/society, and self.

Under each heading, include important elements: home (husband, kids), self (health, spirit), and so on. Then rank each element on your list from zero to 100 according to (a) its importance to you and (b) how much attention it gets each week. How closely do the numbers match? Finally, in each category, look at the three to five entries you rated most important: Ask yourself what the expectations are (your husband's, clients', your own) and how well you're meeting them. With this knowledge, you can figure out better work-life deals for yourself. "The solution," Friedman says, "shouldn't be how to compromise your career but how to enhance performance overall—professional and personal."

Going nowhere fast? Here's how to get ahead at work