My Mother's Nature

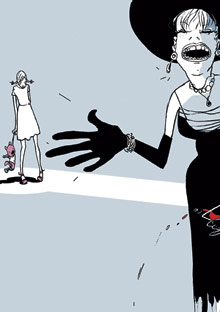

Illustration: Istvan Banyai

It's usually about nurturing her child—not swilling vodka, hitting on her daughter's boyfriends, and setting her up with frat boys by stranding her at the bar. A daughter relives her stormy relationship with her mother and the way she finally found the calm within it.

Lots of daughters have difficult mothers. I knew that. So I didn't spend a lot of time questioning my own mother's eccentricities. The Thanksgiving I went to stay with her and my stepfather, Butch, at their Florida vacation condo, for instance, I was only hoping the change of scenery might distract her from her usual mission of trying to get it through my head just how much I was screwing up my life. Instead my mother directed Butch to drive straight from the airport to a noisy college bar. She ordered a double vodka and struck up a conversation with the baseball-capped frat boys at the next table. “They're nice! And good-lookin', too!” she shouted across the table at me. “Why don't you move over here by me and talk to them? You're not going to get a boyfriend sitting there waiting for Prince Charming to find you!”

“Mom,” I feebly protested. “They're too young for me.”

“Bullshit!” she declared and launched into a boilerplate tirade, which might have been titled “Why You Are a Dumb-ass Who Wouldn't Know an Eligible Bachelor If He Hit You on the Head with a Dead Polecat.”

My mother never met an adult male I wouldn't have been better off marrying rather than doing whatever it was I thought I was doing up in New York. I excused myself to go to the ladies' room. I'd sat through the speech. All I had to do now was sit through a plate of chicken wings and some nachos.

When I came back, my mother and Butch weren't at the table. I looked around. They weren't anywhere in the restaurant.

One of the frat boys leaned over and said, “Your mother said she had to go. She asked if we'd give you a ride home.”

My mother was right about one thing. The frat boys were nice. But I had only a vague notion of where “home” was (I'd visited the condo briefly once before) and had no phone number or address. I sat in on the boys' night out for hours, feeling as though there was a large rock in my rib cage, trying to let them carry on the kind of conversations 20-year-old guys usually have, instead of the kind they have when an older woman has been foisted upon them by her mother. Sometime much later, a couple of them drove me around for an hour or so, until eventually a road looked familiar, and then another road, and then another.

The next day, my mother greeted me with a cheery “Did you have fun?” With all the gumption I could muster, I said, “Not really.”

“Well, that doesn't surprise me,” she said. “You're not a people person like me. You're more like your daddy—as mean as a snake.” This snake business was a favorite leitmotif of Mom's. I had never thought my father was mean. It's true that I didn't spend as much time with him as with my mother (his second wife didn't much welcome my brother and me), but to my mind the man bore more resemblance to a Labrador retriever than he did to a snake.

My mother, however, is a people person—if being a people person means loving an audience. She's a flamboyant former Southern belle, Tallulah Bankhead playing the role of Carol Brady. As you'd expect, the miscasting did make for moments of comedy. My friends thought my mother was a blast, since she told dirty jokes and smoked and drank with us. The local society portrait painter—adored by my mother's country club friends for portraying them as, say, wood nymphs in paintings with titles like Starshine and Raindance—pretty much nailed our relationship: She painted my mother as the sun, smiling and surrounded by a dazzling nimbus of gold rays. I became the moon, looking wan on a blue background and draped in ghostly white. My mother hung her portrait over the mantelpiece in her living room. She hung mine on the landing of the stairs leading up to the spare bedroom.