The Effects of Child Neglect

What happens to a child who grows up with virtually no parenting, love, affection or human touch? "Nearly everything we learn about being human—how to speak, how to walk, everything—comes from the people who raise us," Oprah says. "Today, we're going to look at what happens when nobody does."

Experts say we can learn a lot about our own humanity by studying children who have been robbed of theirs. Over the years, cases of severe neglect have shocked and appalled people around the world.

In March 2008, a Honduran boy named Jason was rescued from a small, dark room where he was kept for years. At just 15 pounds, he was the size of an average 2 year old, but shockingly, he was 9 years old.

These incidents also happen close to home. In 1997, Texas authorities discovered a 9-year-old girl living in squalor. Her name was Victoria, and she couldn't speak or make eye contact. At the time, she hated wearing clothes and feared cars, doorways and toilets.

Victoria was taken in by a foster family, and since then, she's learned to use the bathroom, dress herself and communicate using simple sign language.

Experts say we can learn a lot about our own humanity by studying children who have been robbed of theirs. Over the years, cases of severe neglect have shocked and appalled people around the world.

In March 2008, a Honduran boy named Jason was rescued from a small, dark room where he was kept for years. At just 15 pounds, he was the size of an average 2 year old, but shockingly, he was 9 years old.

These incidents also happen close to home. In 1997, Texas authorities discovered a 9-year-old girl living in squalor. Her name was Victoria, and she couldn't speak or make eye contact. At the time, she hated wearing clothes and feared cars, doorways and toilets.

Victoria was taken in by a foster family, and since then, she's learned to use the bathroom, dress herself and communicate using simple sign language.

Dr. Bruce Perry is a world-renowned child psychiatrist and the author of The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog, one of the foremost books on extreme child abuse. Oprah says he's also the first person she called when she had a crisis at the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy in 2007.

While extreme cases of child neglect may make headlines, Dr. Perry says these examples are just the tip of the iceberg. "Most people don't realize this, but there are twice as many neglected children in the United States as there are physically and sexually abused combined," he says.

Dr. Perry says at least 500,000 children every year are neglected by their caregivers. "It's like a silent epidemic," he says. "From a functional perspective for the developing child, neglect is the absence of necessary stimulation required to build a certain part of the brain so it can function normally."

When a child doesn't get enough stimulation early in life, Dr. Perry says the brain may develop differently. "That changes all kinds of functions, including the ability to form and maintain relationships," he says.

While extreme cases of child neglect may make headlines, Dr. Perry says these examples are just the tip of the iceberg. "Most people don't realize this, but there are twice as many neglected children in the United States as there are physically and sexually abused combined," he says.

Dr. Perry says at least 500,000 children every year are neglected by their caregivers. "It's like a silent epidemic," he says. "From a functional perspective for the developing child, neglect is the absence of necessary stimulation required to build a certain part of the brain so it can function normally."

When a child doesn't get enough stimulation early in life, Dr. Perry says the brain may develop differently. "That changes all kinds of functions, including the ability to form and maintain relationships," he says.

Photo: Melissa Lyttle/St. Petersburg Times/ZUMA

In the summer of 2008, The St. Petersburg Times broke a story of extreme child neglect that caused public outcry across the state of Florida and beyond. The story centered on a little girl named Danielle...a child no one knew existed.

Neighbors knew a woman lived with her boyfriend and two sons in a house on their street but said they had never seen Danielle. Then, one day, a neighbor told authorities that she saw a little girl lift a dirty blanket and peer out of a broken window.

On July 13, 2005, police officers responded to the neighbor's call and went to the home in question. Once inside, Detective Mark Holste says he was struck by the living conditions. "There was animal feces on the floor. There was chewed-up food everywhere," he says. "There were cigarette butts everywhere, and there were spider webs hanging from the ceiling. There were thousands and thousands of cockroaches."

Watch Detective Holste return to the crime scene.

The officers found Danielle in one of the bedrooms. "When she saw me, her mouth dropped open, and she did the little crab walk into the corner, tucked her knees up to her, wrapped her hands around her knees and started making grunting noises," Detective Holste says. "I noticed she had insect bites from the top of her head to the tips of her toes. The only thing she was wearing was a diaper, which had been soiled for quite some time, and she weighed nothing."

Detective Holste says he picked Danielle up into his arms and carried her into the living room, where her mother was waiting. "I said: 'How could this happen? How could you let this happen?'" he says. "And she said, 'I'm doing the very best I can.' And I told her, 'Your best is not good enough.'"

At the time, Danielle was 6 years old and weighed just 43 pounds.

Neighbors knew a woman lived with her boyfriend and two sons in a house on their street but said they had never seen Danielle. Then, one day, a neighbor told authorities that she saw a little girl lift a dirty blanket and peer out of a broken window.

On July 13, 2005, police officers responded to the neighbor's call and went to the home in question. Once inside, Detective Mark Holste says he was struck by the living conditions. "There was animal feces on the floor. There was chewed-up food everywhere," he says. "There were cigarette butts everywhere, and there were spider webs hanging from the ceiling. There were thousands and thousands of cockroaches."

Watch Detective Holste return to the crime scene.

The officers found Danielle in one of the bedrooms. "When she saw me, her mouth dropped open, and she did the little crab walk into the corner, tucked her knees up to her, wrapped her hands around her knees and started making grunting noises," Detective Holste says. "I noticed she had insect bites from the top of her head to the tips of her toes. The only thing she was wearing was a diaper, which had been soiled for quite some time, and she weighed nothing."

Detective Holste says he picked Danielle up into his arms and carried her into the living room, where her mother was waiting. "I said: 'How could this happen? How could you let this happen?'" he says. "And she said, 'I'm doing the very best I can.' And I told her, 'Your best is not good enough.'"

At the time, Danielle was 6 years old and weighed just 43 pounds.

Officers removed Danielle from her home and took her straight to the emergency room. Dr. Rodriguez, the physician who treated her, says that although Danielle was almost 7 years old, her behavior and language skills were similar to those of a 6-month-old baby.

"She wasn't able to feed herself, but she would feed from a bottle," Dr. Rodriguez says. "Danielle was malnourished, and she was dirty and had several insect bites."

Danielle's physical appearance wasn't what shocked Dr. Rodriguez most. The most profound effect of her neglect was how she reacted to human beings. "She wouldn't make eye contact. She frequently pushed us away, kicked us away," Dr. Rodriguez says. "[She] would snarl at us, frankly. She behaved like an injured animal. We realized the safest place would be one of the caged cribs."

"She wasn't able to feed herself, but she would feed from a bottle," Dr. Rodriguez says. "Danielle was malnourished, and she was dirty and had several insect bites."

Danielle's physical appearance wasn't what shocked Dr. Rodriguez most. The most profound effect of her neglect was how she reacted to human beings. "She wouldn't make eye contact. She frequently pushed us away, kicked us away," Dr. Rodriguez says. "[She] would snarl at us, frankly. She behaved like an injured animal. We realized the safest place would be one of the caged cribs."

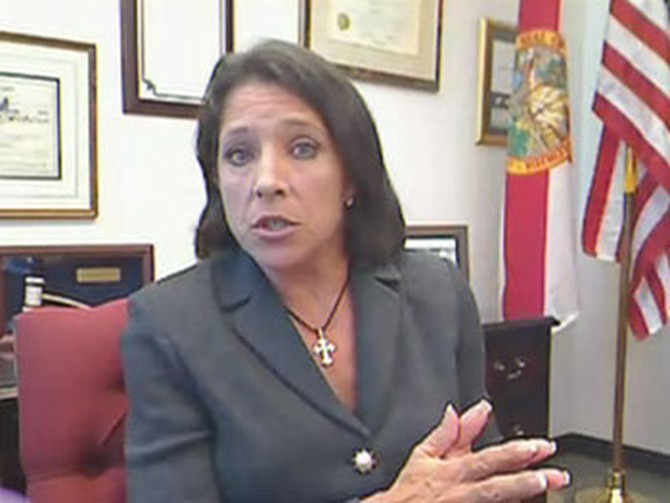

Once Danielle was safe, Tracy Sheehan—an attorney who has since become a circuit court judge—was appointed as her legal advocate. Judge Sheehan became Danielle's voice in the courtroom.

In all her years in public service, Judge Sheehan says she's never seen anything like Danielle's case. "I daresay most of us have not. It was really mind-boggling that a child was so devoid of social skills. She couldn't grab her sippy cup. She couldn't do positive/negative reinforcement regarding potty training," she says. "It was just the saddest thing that this child ... was being raised like a potted plant, literally."

In all her years in public service, Judge Sheehan says she's never seen anything like Danielle's case. "I daresay most of us have not. It was really mind-boggling that a child was so devoid of social skills. She couldn't grab her sippy cup. She couldn't do positive/negative reinforcement regarding potty training," she says. "It was just the saddest thing that this child ... was being raised like a potted plant, literally."

After Danielle's story broke, documents surfaced that showed Florida's Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) had received previous complaints about Danielle's mother. Child advocates made two visits to the home in 2002—three years prior to her rescue—but they rated Danielle's risk as "low" and left her in her mother's care.

At the time, Judge Sheehan says the allegation was that 4-year-old Danielle was being left with inappropriate caretakers while her mother was out of the house. "Our social service agency responded to the home, and the reports indicated that the child was sleeping on one occasion," she says. "They didn't get her up and speak to her and put themselves in a position to assess her developmental skills."

Though DCFS agents offered Danielle's mother a daycare referral, reports indicate that she was not receptive. "[They] encouraged her to put the child in daycare. She refused," Judge Sheehan says. "She later testified at trial she didn't think she needed any services. She was doing the best she could, and of course, hindsight is 20/20. Had we known what we know now, we would have removed her. Certainly, it would have been better to have done that."

By the time she got the case, Judge Sheehan says it was time to look forward and try to help Danielle, as opposed to dwelling on the past.

At the time, Judge Sheehan says the allegation was that 4-year-old Danielle was being left with inappropriate caretakers while her mother was out of the house. "Our social service agency responded to the home, and the reports indicated that the child was sleeping on one occasion," she says. "They didn't get her up and speak to her and put themselves in a position to assess her developmental skills."

Though DCFS agents offered Danielle's mother a daycare referral, reports indicate that she was not receptive. "[They] encouraged her to put the child in daycare. She refused," Judge Sheehan says. "She later testified at trial she didn't think she needed any services. She was doing the best she could, and of course, hindsight is 20/20. Had we known what we know now, we would have removed her. Certainly, it would have been better to have done that."

By the time she got the case, Judge Sheehan says it was time to look forward and try to help Danielle, as opposed to dwelling on the past.

Oprah Show producers contacted Florida's DCFS to find out why Danielle hadn't been removed from the home sooner.

They said: "It is sad to realize the Department of Children and Families was in a position to help Danielle years before her suffering became widely known. We understand that speaking to Danielle during the first investigation would have allowed us more insight into the environment she was forced to endure. We have worked tirelessly to improve our child protective system."

They said: "It is sad to realize the Department of Children and Families was in a position to help Danielle years before her suffering became widely known. We understand that speaking to Danielle during the first investigation would have allowed us more insight into the environment she was forced to endure. We have worked tirelessly to improve our child protective system."

Dr. Perry has treated children who've survived genocides, as well as boys and girls raised in closets and cages. These obvious incidents of trauma and neglect can alter young lives forever. In homes across the country, however, Dr. Perry says parents may be stunting their child's development unintentionally.

"Our modern world is very different than the world that our brain is engineered for. In the world that human beings have lived in for centuries, there were many, many, many more people in our lives—aunties, grannies, extended family. We were in continuous relational interaction with each other," he says. "The developing child under the age of 6 had at least, in those typical settings, four developmentally mature individuals who would help protect, enrich and nurture these kids."

Thanks to the loving attention of many family members, Dr. Perry says the part of the brain involved in relational interaction got lots of stimulation. This helped people grow up with a tremendous sense of empathy.

Over the years, things have changed. "In the modern world, we have childcare settings where there's one adult and eight, nine, 10 kids," he says. "Then, in a home, you've got a poor, isolated mother who's got multiple children."

The consequence isn't what Dr. Perry would call neglect. "I would say that it is underdevelopment of a potential," he says. "Broadly, we are underexpressing the potential of our children to be humane. ... We aren't providing equal amounts of social, relational and emotional experiences to help them be compassionate."

"Our modern world is very different than the world that our brain is engineered for. In the world that human beings have lived in for centuries, there were many, many, many more people in our lives—aunties, grannies, extended family. We were in continuous relational interaction with each other," he says. "The developing child under the age of 6 had at least, in those typical settings, four developmentally mature individuals who would help protect, enrich and nurture these kids."

Thanks to the loving attention of many family members, Dr. Perry says the part of the brain involved in relational interaction got lots of stimulation. This helped people grow up with a tremendous sense of empathy.

Over the years, things have changed. "In the modern world, we have childcare settings where there's one adult and eight, nine, 10 kids," he says. "Then, in a home, you've got a poor, isolated mother who's got multiple children."

The consequence isn't what Dr. Perry would call neglect. "I would say that it is underdevelopment of a potential," he says. "Broadly, we are underexpressing the potential of our children to be humane. ... We aren't providing equal amounts of social, relational and emotional experiences to help them be compassionate."

Danielle's biological mother is a 51-year-old single mom with two sons in their 20s. After Danielle was taken out of their home, her mother was arrested. After being released, she agreed to give this interview to Bay News 9, a local television station.

Reporter: They say Danielle was a feral child.

Danielle's mother: I don't know what that...

Reporter: Meaning that she never had any interaction with humans.

Danielle's mother: No, that is not true. They accused me of making her autistic—environmental. And that's a crock. You cannot make a child autistic. You cannot make a child retarded. They just made me sound like I was some kind of a monster, and I'm not a monster. I love my baby. The only thing I was guilty of was a dirty house, and it cost me my child. I'm sorry. I love that baby. She's my life.

Reporter: They say Danielle was a feral child.

Danielle's mother: I don't know what that...

Reporter: Meaning that she never had any interaction with humans.

Danielle's mother: No, that is not true. They accused me of making her autistic—environmental. And that's a crock. You cannot make a child autistic. You cannot make a child retarded. They just made me sound like I was some kind of a monster, and I'm not a monster. I love my baby. The only thing I was guilty of was a dirty house, and it cost me my child. I'm sorry. I love that baby. She's my life.

Lane DeGregory, the St. Petersburg Times reporter who broke Danielle's story, says she was surprised by the responses Danielle's mother gave during her interview. "She didn't think she'd done anything wrong. Despite all the evidence from the doctors and the detectives and the social workers, she just kept saying that she took care of Danielle the best she could," Lane says. "[She said] 'Danielle ate out of a baby bottle. She was hungry all the time. She was only skinny because her mother herself had been skinny when she was young and there was nothing wrong with her.'"

As for her state of mind, Lane says Danielle's mother was in denial. "She didn't take any responsibility for her actions. She felt a victim herself of bad luck, of the system, of police not talking to her."

When Lane asked if she had anything to regret, she says Danielle's mother said she regretted moving to Florida. "That was it. There was nothing about what had happened to her daughter or the condition that her daughter was in," Lane says. "Her only regret was moving here."

As for her state of mind, Lane says Danielle's mother was in denial. "She didn't take any responsibility for her actions. She felt a victim herself of bad luck, of the system, of police not talking to her."

When Lane asked if she had anything to regret, she says Danielle's mother said she regretted moving to Florida. "That was it. There was nothing about what had happened to her daughter or the condition that her daughter was in," Lane says. "Her only regret was moving here."

Keep Reading

According to Judge Sheehan, the state of Florida charged Danielle's mother with child neglect, and her parental rights were terminated. "After she had her rights terminated, she actually appealed not only to the first layer of the Appellate Courts but to the Florida Supreme Court," Judge Sheehan says. "She fought very vigorously for her parental rights."

Eight months after Danielle was rescued, her mother was finally arrested. "She spent about 26 hours in jail, was released and vigorously fought against the criminal charges," Judge Sheehan says. "Ultimately, she entered a plea and the state gave her a deal." Danielle's mother was sentenced two years of house arrest followed by three years of probation.

"So she, all along—other than that 26 hours—is a free woman who is out to go on about life," she says. "Poor Danielle is left with the horrible effects for the rest of her life."

The Oprah Winfrey Show contacted Danielle's biological mother for a statement through her attorney. Her attorney has not returned our calls.

Eight months after Danielle was rescued, her mother was finally arrested. "She spent about 26 hours in jail, was released and vigorously fought against the criminal charges," Judge Sheehan says. "Ultimately, she entered a plea and the state gave her a deal." Danielle's mother was sentenced two years of house arrest followed by three years of probation.

"So she, all along—other than that 26 hours—is a free woman who is out to go on about life," she says. "Poor Danielle is left with the horrible effects for the rest of her life."

The Oprah Winfrey Show contacted Danielle's biological mother for a statement through her attorney. Her attorney has not returned our calls.

After her mother's parental rights were terminated, the next step was to find a new home for Danielle. "I'd like to think that I did everything to keep Danielle's case from falling through the cracks," says Garet White, Danielle's case worker.

A temporary solution wasn't an option for Garet—she was looking for a family who would always be there for Danielle. "It was going to be hard work to adopt a 9-year-old who was wearing diapers, who was drinking out of a bottle, who doesn't speak," Garet says. "It was going to take a very special family."

A temporary solution wasn't an option for Garet—she was looking for a family who would always be there for Danielle. "It was going to be hard work to adopt a 9-year-old who was wearing diapers, who was drinking out of a bottle, who doesn't speak," Garet says. "It was going to take a very special family."

Those special parents turned out to be Bernie and Diane Lierow. "We went to an event put on by the Heart Gallery, where they had probably over a hundred children available for adoption there that we got to meet," Diane says.

Photographs of children who could not attend were hanging on a board at the event. "I just kept being drawn back to one photo, even though there were all these children running around having a great time that I could meet in person," Diane says.

When Bernie saw the photo of Danielle, he says he knew she was his daughter. "I knew it right from the beginning," he says.

Photographs of children who could not attend were hanging on a board at the event. "I just kept being drawn back to one photo, even though there were all these children running around having a great time that I could meet in person," Diane says.

When Bernie saw the photo of Danielle, he says he knew she was his daughter. "I knew it right from the beginning," he says.

When Bernie and Diane brought Danielle home, they realized the extent of Danielle's underdevelopment. "She was a couple months from being 8 years old," Diane says. "Developmentally, she was anywhere between 6 months to maybe 18 to 24 months, depending on the skill that was being evaluated."

During Danielle's first days in her new home, Bernie says she would throw tantrums seven or eight times a day. "She would scream at the top of her lungs, she would stomp, she would flail her arms, she would throw herself on the floor—they were pretty spectacular," Diane says.

Food was a constant concern for Danielle. "She was thinking about it all the time," Diane says. "As long as there was food out, she would eat it until she threw up. She would drink until she threw up. She didn't know when to quit, because she didn't know when she would see it again."

Instead of toys, Diane says Danielle would play with her shoes and socks. "Just sort of throw them around as if they were a toy. I don't think she understood that her shoes and socks weren't to play with," she says. "I don't think she really had much of anything to play with for a long time, so she just amused herself with whatever she could find, I guess."

Although she couldn't speak, Diane says she believes Danielle remembers her old life. "Yes, I do because when she first came, she would have nightmares. About every hour or two she would wake up screaming."

During Danielle's first days in her new home, Bernie says she would throw tantrums seven or eight times a day. "She would scream at the top of her lungs, she would stomp, she would flail her arms, she would throw herself on the floor—they were pretty spectacular," Diane says.

Food was a constant concern for Danielle. "She was thinking about it all the time," Diane says. "As long as there was food out, she would eat it until she threw up. She would drink until she threw up. She didn't know when to quit, because she didn't know when she would see it again."

Instead of toys, Diane says Danielle would play with her shoes and socks. "Just sort of throw them around as if they were a toy. I don't think she understood that her shoes and socks weren't to play with," she says. "I don't think she really had much of anything to play with for a long time, so she just amused herself with whatever she could find, I guess."

Although she couldn't speak, Diane says she believes Danielle remembers her old life. "Yes, I do because when she first came, she would have nightmares. About every hour or two she would wake up screaming."

Dr. Kathi Armstrong was the first psychologist to evaluate Danielle. "When I first met her, she came in with a diagnosis of neglect and malnutrition, possible pervasive developmental disorder and mental retardation," Dr. Armstrong says.

Danielle was evaluated in a playroom filled with toys, but Dr. Armstrong says she didn't know how to play. "She just wandered around up on her toes kind of. She would bite her hand, pull out chunks of hair," Dr. Armstrong says. "She would pick up objects, flip them in front of her face."

Communication was also an issue. "She didn't like to be touched. She didn't respond to any of the things that typical young children respond to, like music or bubbles or soothing or tickling," Dr. Armstrong says. "You'd look in those big, beautiful, brown eyes, and they were vacant."

Danielle was evaluated in a playroom filled with toys, but Dr. Armstrong says she didn't know how to play. "She just wandered around up on her toes kind of. She would bite her hand, pull out chunks of hair," Dr. Armstrong says. "She would pick up objects, flip them in front of her face."

Communication was also an issue. "She didn't like to be touched. She didn't respond to any of the things that typical young children respond to, like music or bubbles or soothing or tickling," Dr. Armstrong says. "You'd look in those big, beautiful, brown eyes, and they were vacant."

Dr. Armstrong says she cannot assess if Danielle was born with the mental disabilities she has now. "We'll never know, because her mother never took her to a doctor from the time she was born," she says. "What we do know is extensive medical tests were run on her, including scans of her brain and genetics and other types of tests, and nothing was found—nothing that can account for the retardation that she has."

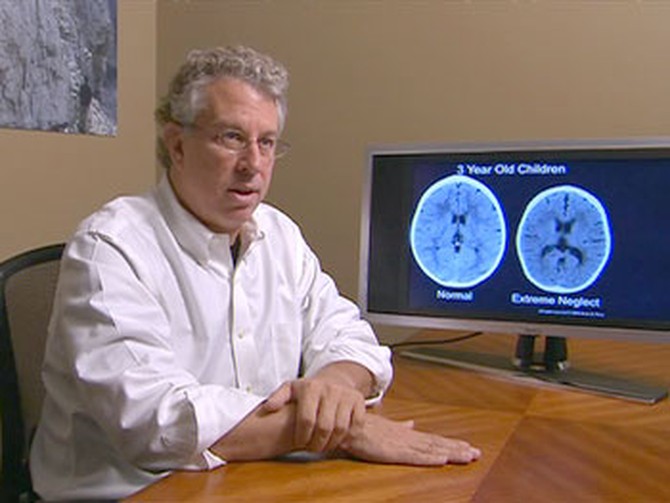

Dr. Perry was one of the first people to use MRI technology to look at the effects inadequate nurturing and touch or lack of touch can have on the brain of a small child.

Dr. Perry compares a brain scan of a normal, healthy 3-year-old child with a child who was severely neglected his first three years of life. "The first thing is that the brain is a little bit smaller. The brains of really severely neglected children tend to be smaller than the brains of children who have not been neglected," he says. "The brain didn't grow and shrink. It just didn't grow.

On the brain scan, Dr. Perry also notices dark spaces in the neglected child's brain. "Big, big ventricular spaces, which will impact sleep, regulation of anxiety, regulation of mood, whether or not you're very happy or sad," he says.

"As you grow, the brain is essentially like a sponge," Dr. Perry says. "It's absorbing all kinds of experiences. So if a child is not held, touched, talked to, interacted with, loved, literally neurons do not make those connections, and many of them actually will die."

Simple things like eye contact, touch, rocking and humming can make all the difference to a baby, Dr. Perry says. "It makes neurons grow, it makes them make connections," he says. "Then, it makes the brain more functional."

Dr. Perry was one of the first people to use MRI technology to look at the effects inadequate nurturing and touch or lack of touch can have on the brain of a small child.

Dr. Perry compares a brain scan of a normal, healthy 3-year-old child with a child who was severely neglected his first three years of life. "The first thing is that the brain is a little bit smaller. The brains of really severely neglected children tend to be smaller than the brains of children who have not been neglected," he says. "The brain didn't grow and shrink. It just didn't grow.

On the brain scan, Dr. Perry also notices dark spaces in the neglected child's brain. "Big, big ventricular spaces, which will impact sleep, regulation of anxiety, regulation of mood, whether or not you're very happy or sad," he says.

"As you grow, the brain is essentially like a sponge," Dr. Perry says. "It's absorbing all kinds of experiences. So if a child is not held, touched, talked to, interacted with, loved, literally neurons do not make those connections, and many of them actually will die."

Simple things like eye contact, touch, rocking and humming can make all the difference to a baby, Dr. Perry says. "It makes neurons grow, it makes them make connections," he says. "Then, it makes the brain more functional."

During the year and a half that Danielle has lived with Bernie and Diane, they say she's come a long way.

Diane says Danielle can now use the bathroom on her own and has learned to use a fork. "For her to be able to actually fork her own food off of her plate and eat it, it took quite a while," Diane says. "Gradually, she got to the point where, at home at least, she doesn't overeat."

Unlike before, Diane says Danielle rarely has temper tantrums. "She smiles and laughs and just seems really happy and content," she says.

Danielle has also grown to love certain activities, like swimming. "She likes to do flips and somersaults underwater," Diane says. "She has a lot of sensory-seeking behaviors, and she likes to go down to the bottom of the pool and feel the deep pressure of the water on her."

As much progress as Danielle has made, Diane says she is less developed in some areas than others. "She has spoken a few words, but if she says something, you don't know if you'll ever hear it again," she says. "They're in there somewhere, but it's as if her brain can't connect to where she's stored them because it's not been developed properly.

Diane says Danielle can now use the bathroom on her own and has learned to use a fork. "For her to be able to actually fork her own food off of her plate and eat it, it took quite a while," Diane says. "Gradually, she got to the point where, at home at least, she doesn't overeat."

Unlike before, Diane says Danielle rarely has temper tantrums. "She smiles and laughs and just seems really happy and content," she says.

Danielle has also grown to love certain activities, like swimming. "She likes to do flips and somersaults underwater," Diane says. "She has a lot of sensory-seeking behaviors, and she likes to go down to the bottom of the pool and feel the deep pressure of the water on her."

As much progress as Danielle has made, Diane says she is less developed in some areas than others. "She has spoken a few words, but if she says something, you don't know if you'll ever hear it again," she says. "They're in there somewhere, but it's as if her brain can't connect to where she's stored them because it's not been developed properly.

Bernie and Diane aren't the only ones adjusting to the new family addition. The Lierows have a 10-year-old named William along with four other sons who are grown and out of the house.

William was included in the discussions about Danielle's adoption, Diane says, and they had him meet her beforehand. "He was taken aback at first and a little afraid of her at first," Diane says. "But they just connected. They work out great together."

Although she was able to have children on her own, Diane says adoption was always on her mind. "I just have felt for a long time, even before I met Bernie, that this was the thing I was supposed to do," she says.

William was included in the discussions about Danielle's adoption, Diane says, and they had him meet her beforehand. "He was taken aback at first and a little afraid of her at first," Diane says. "But they just connected. They work out great together."

Although she was able to have children on her own, Diane says adoption was always on her mind. "I just have felt for a long time, even before I met Bernie, that this was the thing I was supposed to do," she says.

Dr. Perry says Diane and Bernie are helping Danielle by stimulating her senses, and giving her the love and attention she craves. "Many years ago, we were very pessimistic about the outcomes of children like this," he says. "But now, since we've started to look at this in a very developmental way and provide these kinds of replacement experiences in the sequence that the brain normally develops, we've seen that children who were essentially going to be institutionalized literally go to college."

When Dr. Armstrong first treated Danielle, she wasn't sure she would ever progress as far as she has. "It's so wonderful to see her, especially the pictures of her in the pool and moving around and showing delight when her parents are holding her," she says. "It warms my heart to see that, because I didn't know if she'd even go that far."

Diane says she's always believed that Danielle has potential. "I could see somebody in her eyes," Diane says. "There's a person in there."

See how Danielle is doing today

How you can help a traumatized child

When Dr. Armstrong first treated Danielle, she wasn't sure she would ever progress as far as she has. "It's so wonderful to see her, especially the pictures of her in the pool and moving around and showing delight when her parents are holding her," she says. "It warms my heart to see that, because I didn't know if she'd even go that far."

Diane says she's always believed that Danielle has potential. "I could see somebody in her eyes," Diane says. "There's a person in there."

See how Danielle is doing today

How you can help a traumatized child

Published 03/03/2009