Wrongfully Accused

It may seem like something you only see in detective shows, but this case of wrongful accusation is painfully real.

On January 20, 1998, the Crowe family—parents Steve and Cheryl, 14-year-old Michael, 12-year-old Stephanie and 9-year-old Shannon—spent the evening visiting with their grandmother at their Escondido, California, home. According to news reports, the night was fairly ordinary—the family spent time with one another and the kids watched some television. After everyone had gone to bed, Cheryl said she heard a pounding noise, then heard her bedroom door open and close. At the time, she thought the noises were from her cats.

The next morning, the family was horrified to discover Stephanie stabbed in her bedroom. Police and paramedics arrived on the scene, but there was nothing they could do.

On January 20, 1998, the Crowe family—parents Steve and Cheryl, 14-year-old Michael, 12-year-old Stephanie and 9-year-old Shannon—spent the evening visiting with their grandmother at their Escondido, California, home. According to news reports, the night was fairly ordinary—the family spent time with one another and the kids watched some television. After everyone had gone to bed, Cheryl said she heard a pounding noise, then heard her bedroom door open and close. At the time, she thought the noises were from her cats.

The next morning, the family was horrified to discover Stephanie stabbed in her bedroom. Police and paramedics arrived on the scene, but there was nothing they could do.

After questioning each member of the family, police turned their focus on Stephanie's brother Michael.

Over the next two days, Michael was interrogated for a total of 10 hours. Michael repeatedly denied killing his sister, until he says detectives began to lie to him about the scientific facts of the case. "We're really at mercy to them for information. They can tell us whatever they want," Michael says. "They told me that there was hair that was going to be mine that didn't exist, blood evidence that didn't exist, and you start doubting yourself."

Watch the interrogation video.

Eventually, Michael says he broke down. "You want me to tell you a little story?" he said. "Okay. Here's the part where I'll start lying."

Over the next two days, Michael was interrogated for a total of 10 hours. Michael repeatedly denied killing his sister, until he says detectives began to lie to him about the scientific facts of the case. "We're really at mercy to them for information. They can tell us whatever they want," Michael says. "They told me that there was hair that was going to be mine that didn't exist, blood evidence that didn't exist, and you start doubting yourself."

Watch the interrogation video.

Eventually, Michael says he broke down. "You want me to tell you a little story?" he said. "Okay. Here's the part where I'll start lying."

One year after Stephanie's murder, charges were dropped against Michael.

DNA tests confirmed Stephanie's blood was found on the sweatshirt of a schizophrenic homeless man named Richard Tuite. Tuite had been seen in the Crowes' neighborhood on the night of the murder. In 2004, jurors found him guilty of manslaughter.

DNA tests confirmed Stephanie's blood was found on the sweatshirt of a schizophrenic homeless man named Richard Tuite. Tuite had been seen in the Crowes' neighborhood on the night of the murder. In 2004, jurors found him guilty of manslaughter.

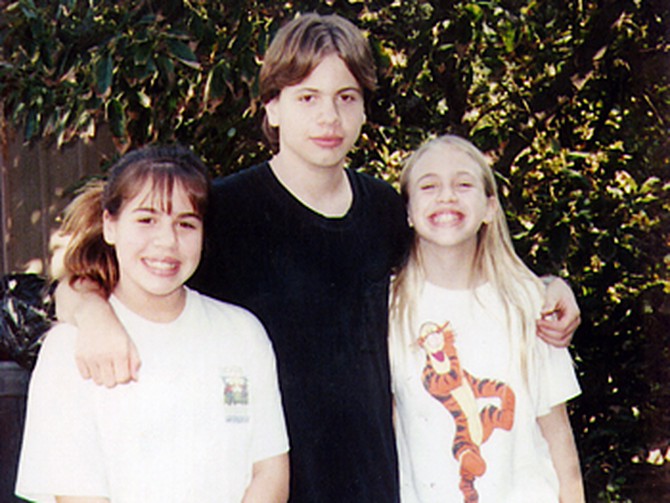

Michael, now 25 years old, says he confessed to his sister's murder after police detectives essentially isolated him from his family. "They strip away all your support systems, and once they've taken your family away from you and your friends, they start chipping away at your own beliefs and memory," Michael says.

Michael says near the end of his interrogation, parts of him started to believe he was guilty. "I wanted them to stop telling me that I was lying and stop treating me the way they were treating me," he says. "If you tell them what you know and believe, they get aggressive. ... And then when you tell them what they want to hear, all of a sudden they're your best friend. And it's just after so much of being treated really aggressively, you just want them to be your friends, so you just start giving them what they want. It's a lot easier that way."

If it weren't for the DNA evidence and the fact that his confession was caught on video, Michael says he could still be in prison appealing his case. "It breaks my heart to know that other people are experiencing this. ... That I might have been the lucky one is just mind-blowing."

Michael says near the end of his interrogation, parts of him started to believe he was guilty. "I wanted them to stop telling me that I was lying and stop treating me the way they were treating me," he says. "If you tell them what you know and believe, they get aggressive. ... And then when you tell them what they want to hear, all of a sudden they're your best friend. And it's just after so much of being treated really aggressively, you just want them to be your friends, so you just start giving them what they want. It's a lot easier that way."

If it weren't for the DNA evidence and the fact that his confession was caught on video, Michael says he could still be in prison appealing his case. "It breaks my heart to know that other people are experiencing this. ... That I might have been the lucky one is just mind-blowing."

Although it's been 11 years since his sister's death, Michael says it doesn't feel like that long ago. "Every time that her birthday rolls around, it's a reminder that we've lost a lot of time with her," he says.

Michael also never got a chance to say goodbye to his little sister. "I wasn't allowed to go to the funeral. It was tough," he says. "It's just something that I live with."

Michael says he does his best to stay positive, but it's not always easy. "I try not to be angry. I try to be a good person about that," he says. "But it's hard not to be angry at the people who took so much from you and who took a bad situation for what could have just been the loss of my sister and just created this big snarl—this big mess—that probably you're never going to work all the way through."

Michael urges anyone in a situation with the police—no matter how minor—to not speak until a lawyer is present. "It's sad that we live in a world where it's like that, but that's the best advice I can give anyone. ... You have your Miranda rights for a reason, and that's what you should be telling your kids. Give them a card with the Miranda rights," he says. "The police are there to protect you, but they can also make mistakes, and you need to protect yourself and your children from that."

Marty Tankleff's fight for justice

Michael also never got a chance to say goodbye to his little sister. "I wasn't allowed to go to the funeral. It was tough," he says. "It's just something that I live with."

Michael says he does his best to stay positive, but it's not always easy. "I try not to be angry. I try to be a good person about that," he says. "But it's hard not to be angry at the people who took so much from you and who took a bad situation for what could have just been the loss of my sister and just created this big snarl—this big mess—that probably you're never going to work all the way through."

Michael urges anyone in a situation with the police—no matter how minor—to not speak until a lawyer is present. "It's sad that we live in a world where it's like that, but that's the best advice I can give anyone. ... You have your Miranda rights for a reason, and that's what you should be telling your kids. Give them a card with the Miranda rights," he says. "The police are there to protect you, but they can also make mistakes, and you need to protect yourself and your children from that."

Marty Tankleff's fight for justice

Published 10/20/2008