Tragic Takeoff

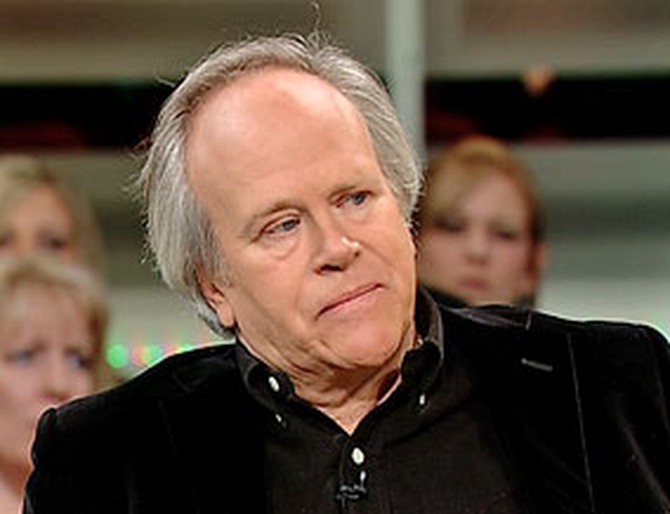

Dick Ebersol and Susan Saint James are a Hollywood power couple. He's the president of NBC Sports and co-creator of Saturday Night Live. She's an Emmy-winning actress who's best known for her starring role in the '80s sitcom Kate & Allie.

They met in 1981 when Susan first hosted SNL, and just six weeks later, they were married. Dick and Susan's family, which included Susan's two children from a previous marriage, quickly grew. They welcomed three sons—Charlie, Willie and, the baby of the family, Teddy—into the world.

After Teddy's birth in 1990, Susan put her acting career on hold and devoted her time to being a full-time mom. In November 2004, the tight-knit clan gathered together in California to celebrate Thanksgiving as a family.

They met in 1981 when Susan first hosted SNL, and just six weeks later, they were married. Dick and Susan's family, which included Susan's two children from a previous marriage, quickly grew. They welcomed three sons—Charlie, Willie and, the baby of the family, Teddy—into the world.

After Teddy's birth in 1990, Susan put her acting career on hold and devoted her time to being a full-time mom. In November 2004, the tight-knit clan gathered together in California to celebrate Thanksgiving as a family.

It was the morning of November 28, 2004. Susan, Dick, and their sons, Charlie and Teddy, boarded a private jet in California. The plane landed at a small Colorado airport, where they dropped off Susan. The rest of the family would be heading east.

Moments after takeoff, the plane carrying Dick, Charlie and Teddy came crashing down. Dick says their plane hit the ground at more than 100 miles an hour and then slid to a stop at the edge of a 60-foot cliff.

Charlie sprung into action as soon as the jet stopped moving. He spotted a tuft of his father's white hair sticking out from beneath a pile of rubble, dug him out and pulled him to safety. Charlie also tried to find his little brother, but before he could, the plane exploded.

Two days later, rescue crews found Teddy's body beneath the plane. Teddy and the two crew members who were also killed had been thrown from the plane on impact.

Dick remembers Teddy's last words very clearly. "He said, 'Dad, I'm scared,'" Dick says. "He didn't say it in a way that he was petrified—he just wanted to pass it on to me to solve it."

Moments after takeoff, the plane carrying Dick, Charlie and Teddy came crashing down. Dick says their plane hit the ground at more than 100 miles an hour and then slid to a stop at the edge of a 60-foot cliff.

Charlie sprung into action as soon as the jet stopped moving. He spotted a tuft of his father's white hair sticking out from beneath a pile of rubble, dug him out and pulled him to safety. Charlie also tried to find his little brother, but before he could, the plane exploded.

Two days later, rescue crews found Teddy's body beneath the plane. Teddy and the two crew members who were also killed had been thrown from the plane on impact.

Dick remembers Teddy's last words very clearly. "He said, 'Dad, I'm scared,'" Dick says. "He didn't say it in a way that he was petrified—he just wanted to pass it on to me to solve it."

Charlie says he still remembers every moment of the crash and its aftermath. "Every time you close your eyes in the day, every time you start your car, every time you get out of bed...it's still there," Charlie says through tears.

Before they found Teddy's body, Dick says Charlie "lived through hell" thinking he hadn't found his little brother inside the plane. "It wasn't until they found Teddy's body did [Charlie] know that he had done everything he possibly could do," Dick says.

The worst moment, Charlie remembers, came minutes after the plane exploded.

"What will be the worst moment in my entire life—I don't care what else happens—I had my cell phone on me, and I had to call my mom," Charlie says. "She was in the mountains, and I said, 'Mom, you've got to come back. The plane crashed. I got dad, but I can't find Ted, and I need you to help.' She was an hour away, and I remember thinking as I made the phone call, she's going to drive for an hour not knowing anything else but these three sentences I just told her."

Before they found Teddy's body, Dick says Charlie "lived through hell" thinking he hadn't found his little brother inside the plane. "It wasn't until they found Teddy's body did [Charlie] know that he had done everything he possibly could do," Dick says.

The worst moment, Charlie remembers, came minutes after the plane exploded.

"What will be the worst moment in my entire life—I don't care what else happens—I had my cell phone on me, and I had to call my mom," Charlie says. "She was in the mountains, and I said, 'Mom, you've got to come back. The plane crashed. I got dad, but I can't find Ted, and I need you to help.' She was an hour away, and I remember thinking as I made the phone call, she's going to drive for an hour not knowing anything else but these three sentences I just told her."

When Susan arrived at the small hospital where Dick and Charlie were being treated, doctors told her they would have to be transferred to a larger hospital in Grand Junction, Colorado. Even though the crash site was near the hospital, Susan says she didn't stay to look for Teddy.

"I just went," she says. "I just left—I left the crash. I left Teddy. I left everything, and I went. I said to somebody later, 'Why would I do that? Why wouldn't I go back to the crash and look for Teddy?' And they said, 'Because instinct is to follow the living—to go with the living.' And the minute I saw Dick he said, 'Teddy's gone. He's gone.' Even though I had held out hope."

Susan says that she always thought if she lost a child, she would "sit down in a chair and never talk again." But, now she says, it just doesn't work that way. In fact, within days of losing Teddy, Susan sat down with NBC's Tim Russert to talk about the tragic accident and thank people for their outpouring of support.

"All I could think [was], 'People are going to be so sad for me,'" Susan says. "You want to make them feel better. It's exhausting sometimes, actually in the early months, because you are trying to make everybody feel better. And then people will say to you, 'What are you doing for you? Now I know you've taken care of your kids and your husband and your life, but what are you doing for Susan?' You know, that isn't even in the nature of a mother."

"I just went," she says. "I just left—I left the crash. I left Teddy. I left everything, and I went. I said to somebody later, 'Why would I do that? Why wouldn't I go back to the crash and look for Teddy?' And they said, 'Because instinct is to follow the living—to go with the living.' And the minute I saw Dick he said, 'Teddy's gone. He's gone.' Even though I had held out hope."

Susan says that she always thought if she lost a child, she would "sit down in a chair and never talk again." But, now she says, it just doesn't work that way. In fact, within days of losing Teddy, Susan sat down with NBC's Tim Russert to talk about the tragic accident and thank people for their outpouring of support.

"All I could think [was], 'People are going to be so sad for me,'" Susan says. "You want to make them feel better. It's exhausting sometimes, actually in the early months, because you are trying to make everybody feel better. And then people will say to you, 'What are you doing for you? Now I know you've taken care of your kids and your husband and your life, but what are you doing for Susan?' You know, that isn't even in the nature of a mother."

The Ebersol family is comforted by the knowledge that Teddy accomplished a lot in his short life. They are especially proud of his success in overcoming a learning disability that had troubled his childhood. "He was, we thought, a very angry kid at the beginning," Charlie says. "By the end, at the end of 14 years, you had this whole person who was best friends with my mom [and] who had created a relationship with my father. ... He was the complete person that you hope you will be when [you] die." While recovering in the hospital after the crash, Charlie says his brother Willie told him something "only a filmmaker could say." Teddy, Willie said, "had a complete arc."

Susan says she considers her support and encouragement of Teddy over the last three years the greatest accomplishment of her life. "He knew how we felt," she says, "[We would tell him], 'Look what you've done with your life, [what] you've achieved! You're such a happy guy now. You're doing so well!"

Susan says she considers her support and encouragement of Teddy over the last three years the greatest accomplishment of her life. "He knew how we felt," she says, "[We would tell him], 'Look what you've done with your life, [what] you've achieved! You're such a happy guy now. You're doing so well!"

Susan shares a poignant story that reveals the maturity Teddy had acquired at such a young age. When she asked her son why he had suddenly developed a fascination with baseball—never having shown the slightest interest in sports—Teddy answered, "I really wanted to find a way to be closer to Dad. I thought baseball would give me that language."

"Usually, [as a parent,] you'll go play a video game with your kid so you can get into what they're thinking about," Susan says. "But it's not that often where a 14-year-old will try to get really up to speed with something that would put him in the language of his dad."

The Ebersols continue to try to focus on Teddy's life, not his death. "It would suck to think of him as a tragic loss," Willie says. "No one wants to be remembered that way. You need to celebrate people's lives."

Teddy's family treasures the writings he left behind. A cherished keepsake is the 37-page autobiography Teddy wrote as an eighth grader. On Teddy's computer, his parents found more beautifully written prose, including one moving story loosely based on a family ski vacation. In it, Teddy touchingly describes being helped down the mountain by his brother: "The shooshing of [Willie's] skis," he wrote, was as if Willie "was pouring a bucket of love all over [me]."

"He was a philosopher," Susan says. At his eighth grade graduation, Teddy gave a speech that began with "an old saying" he had recently coined: "I follow, therefore I lead," he told his audience. Teddy ended his speech with more words of wisdom: "The finish line is just the beginning of a whole new race."

"Usually, [as a parent,] you'll go play a video game with your kid so you can get into what they're thinking about," Susan says. "But it's not that often where a 14-year-old will try to get really up to speed with something that would put him in the language of his dad."

The Ebersols continue to try to focus on Teddy's life, not his death. "It would suck to think of him as a tragic loss," Willie says. "No one wants to be remembered that way. You need to celebrate people's lives."

Teddy's family treasures the writings he left behind. A cherished keepsake is the 37-page autobiography Teddy wrote as an eighth grader. On Teddy's computer, his parents found more beautifully written prose, including one moving story loosely based on a family ski vacation. In it, Teddy touchingly describes being helped down the mountain by his brother: "The shooshing of [Willie's] skis," he wrote, was as if Willie "was pouring a bucket of love all over [me]."

"He was a philosopher," Susan says. At his eighth grade graduation, Teddy gave a speech that began with "an old saying" he had recently coined: "I follow, therefore I lead," he told his audience. Teddy ended his speech with more words of wisdom: "The finish line is just the beginning of a whole new race."

The Ebersols say the first anniversary of Teddy's death was a difficult but a meaningful time for the whole family. "[The children] chose to come home," Dick says. "Susan and I thought we should go someplace else for [the anniversary], and all four of the kids said, 'No, no, we want to go home.'"

"I thought it was the closest I'd ever been with [the family]," Charlie says. "The anniversary [day] was tough, but that week ... I never felt closer and happier to be with my family. We were all worried that it was going to be this miserable week, ... [but] it was a celebration."

"I thought it was the closest I'd ever been with [the family]," Charlie says. "The anniversary [day] was tough, but that week ... I never felt closer and happier to be with my family. We were all worried that it was going to be this miserable week, ... [but] it was a celebration."

Soon after Teddy's death, Susan encouraged her family to reject bitterness and anger. "Having a resentment is like taking poison," she says.

"Out of all of this horror, one incredible thing happened," Dick says. "Susan gave everybody in our family this incredible release by saying that it was okay to cry, it was okay to be sad if we wanted to be the rest of our lives—but we weren't going to be bitter, we weren't going to be angry, we weren't going to be mad."

Coming together against feelings of anger, the family feels united in their effort to support and encourage one another after the tragedy. Charlie says he now calls his family before any flight. "Willie asks me one question," Charlie says. "He says, 'Are you happy?' And if I say yes, then I'm okay to fly."

"Out of all of this horror, one incredible thing happened," Dick says. "Susan gave everybody in our family this incredible release by saying that it was okay to cry, it was okay to be sad if we wanted to be the rest of our lives—but we weren't going to be bitter, we weren't going to be angry, we weren't going to be mad."

Coming together against feelings of anger, the family feels united in their effort to support and encourage one another after the tragedy. Charlie says he now calls his family before any flight. "Willie asks me one question," Charlie says. "He says, 'Are you happy?' And if I say yes, then I'm okay to fly."

Published 02/02/2006