Between Life and Death

According to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), crystal methamphetamine (meth) is the number one drug in rural America. And now, the crystal meth epidemic is spreading like wildfire in cities and suburbs across America. Crystal meth has become the new drug of choice for everyone from soccer moms to working moms. Even grade school students are being caught in its deadly grip.

Meth is cheap and easy to make. The recipe includes over-the-counter cold medicine, household cleaners and toxic chemicals like battery acid. This drug crisis has forced many store owners to put cold remedies under lock and key. Thousands of homemade meth labs are popping up in kitchens, garages, even inside cars. In one Iowa town officials were forced to ban children from bringing baked goods to school because so many parents are cooking meth with the same utensils.

It's cheap, instantly addictive, often deadly—and it's probably already in your neighborhood.

Meth is cheap and easy to make. The recipe includes over-the-counter cold medicine, household cleaners and toxic chemicals like battery acid. This drug crisis has forced many store owners to put cold remedies under lock and key. Thousands of homemade meth labs are popping up in kitchens, garages, even inside cars. In one Iowa town officials were forced to ban children from bringing baked goods to school because so many parents are cooking meth with the same utensils.

It's cheap, instantly addictive, often deadly—and it's probably already in your neighborhood.

Chantel looks like an all-American 17-year-old girl. Her mother is a teacher's assistant and her father sells insurance. She works at an espresso shop. But she's addicted to crystal meth.

Chantel and her family live outside Granite Falls, Washington. She says she's been addicted to meth for a year and a half, after being introduced by friends, and she says she was instantly hooked from the very first hit. Since that time, she says the longest she's gone without using meth was 40 days. In that time, Chantel says, "I was having a ball. I was going to church to see if that was the way for me. I was having fun, hanging out with sober people. And then it was just in front of me one night and I did it and I was hooked again."

On one occasion, Chantel says she stayed up for 13 straight days, getting high every 20 minutes. "Meth makes you have this burst of energy," she explains. "And if you keep smoking it, you'll keep that energy burst." Was she worried about overdosing during that two-week binge? "You don't worry about anything," Chantel says. "You don't have any thought in your mind besides, 'Let's hit it again.'"

Chantel and her family live outside Granite Falls, Washington. She says she's been addicted to meth for a year and a half, after being introduced by friends, and she says she was instantly hooked from the very first hit. Since that time, she says the longest she's gone without using meth was 40 days. In that time, Chantel says, "I was having a ball. I was going to church to see if that was the way for me. I was having fun, hanging out with sober people. And then it was just in front of me one night and I did it and I was hooked again."

On one occasion, Chantel says she stayed up for 13 straight days, getting high every 20 minutes. "Meth makes you have this burst of energy," she explains. "And if you keep smoking it, you'll keep that energy burst." Was she worried about overdosing during that two-week binge? "You don't worry about anything," Chantel says. "You don't have any thought in your mind besides, 'Let's hit it again.'"

Chantel says she actually has overdosed before, though it didn't stop her from using meth again. "I was passed out in a bed," she says. "I woke up the next day at noon and there were people around me and there was blood on the bed. They were crying and they were like, 'We're never doing it again. We're never going to do it again.' I was like, 'What's going on?' They said that every five minutes I'd wake up and I'd be screaming at the top of my lungs. Nobody took me to the hospital because everyone was too scared because they were all high."

And where did she do meth? "At friends' [houses], everywhere," she says. "All your friends, adults, even, in town [are doing it]. … I probably have one friend who doesn't do it."

"I've done many things on the drug that I regret," Chantel says. "I've put my family through everything. … I had a best friend since third grade, and I got hooked on meth and she left, so I don't have that friend anymore. I've dated a lot of people who did drugs to get free drugs."

And where did she do meth? "At friends' [houses], everywhere," she says. "All your friends, adults, even, in town [are doing it]. … I probably have one friend who doesn't do it."

"I've done many things on the drug that I regret," Chantel says. "I've put my family through everything. … I had a best friend since third grade, and I got hooked on meth and she left, so I don't have that friend anymore. I've dated a lot of people who did drugs to get free drugs."

Oprah: Do you like the situation you're in now?

Chantel: Not at all.

Oprah: Do you like yourself?

Chantel: No.

Oprah: What do you think is going to happen to you?

Chantel: I think that I'm going to die soon.

Oprah: And is that okay with you?

Chantel: No.

Oprah: But you don't think you can beat it?

Chantel: I think it's really hard to beat it, especially when I get upset. I think with my family's support I can probably do it. But I just run from everything.

Oprah: Do you like who you are off the drug?

Chantel: Yes.

Chantel: Not at all.

Oprah: Do you like yourself?

Chantel: No.

Oprah: What do you think is going to happen to you?

Chantel: I think that I'm going to die soon.

Oprah: And is that okay with you?

Chantel: No.

Oprah: But you don't think you can beat it?

Chantel: I think it's really hard to beat it, especially when I get upset. I think with my family's support I can probably do it. But I just run from everything.

Oprah: Do you like who you are off the drug?

Chantel: Yes.

Chantel says that when she's on meth, she would go to school, go to work and come home all while covering up that she was high. She was so good at covering it up that her mother, Penni, didn't realize that she was addicted. "Then my sister, [Kortnie,] said, 'Chantel's in La-La Land,'" Chantel says. "And my mom asked the school counselor to give me a UA [urine analysis]. And she did and I was positive for methamphetamines."

After finding out, Penni resorted to locking Chantel in the house "At the time [I did that because] I knew that she's safe with me."

After finding out, Penni resorted to locking Chantel in the house "At the time [I did that because] I knew that she's safe with me."

Chantel's sister, Kortnie, has also felt the effects of Chantel's meth addiction. "I got a phone call from my mom, crying and telling me I needed to get over there," Kortnie says. "I thought she was dead."

Debra Jay, an addiction specialist and author of Love First: A New Approach to Intervention for Alcoholism and Drug Addiction (A Hazelden Guidebook), led Kortnie and Penni through an intervention for Chantel. Debra says that meth usage creates "an addiction we can't even imagine."

"Parents get sucked in," Debra says. "You look at this girl and she's so beautiful and you want to believe her. And Penni would believe her over and over again because she thought she was talking to her daughter… And what Penni and all the other mothers and fathers in this country don't understand is it's the addiction talking to them. It's a little bit like The Exorcist, where all of a sudden she looks like the cute little girl, and her head is spinning on her shoulders and she's spewing things out at you. That's what you live with."

At the beginning of the intervention, Debra tells Chantel, "I'm here for one reason and one reason only: your family loves you so much and they wrote some letters, and they want to read those to you now."

"Parents get sucked in," Debra says. "You look at this girl and she's so beautiful and you want to believe her. And Penni would believe her over and over again because she thought she was talking to her daughter… And what Penni and all the other mothers and fathers in this country don't understand is it's the addiction talking to them. It's a little bit like The Exorcist, where all of a sudden she looks like the cute little girl, and her head is spinning on her shoulders and she's spewing things out at you. That's what you live with."

At the beginning of the intervention, Debra tells Chantel, "I'm here for one reason and one reason only: your family loves you so much and they wrote some letters, and they want to read those to you now."

Chantel's mother and sister confronted her with their love and pleas. "I've seen how the drug has changed you and I know it's not the real you. I know you never wanted this for yourself," her sister, Kortnie, reads. "Without you, I don't know where I would be. If it were me, I know you'd want to do anything possible to save my life and you'd never give up on me. I want you to be my best friend and be in my future forever. We have so many good memories that we have yet to make. I want you to know I will always stand by you."

Next, Penni speaks to her daughter. "From the moment you came into this world and I looked down at your beautiful face, my heart was filled with so much joy and love. The times we don't know where you are, what you're doing, is a fear and pain I can never explain to another person, how much it aches inside believing I may never see you again. I cannot bear a life without you. I tell you often what a bright future I see for you ... Sometimes it is those who experience the most pain, the pain I see you go through, who get past it and do the greatest things. Please accept the help we are offering you. I love you very much."

Next, Penni speaks to her daughter. "From the moment you came into this world and I looked down at your beautiful face, my heart was filled with so much joy and love. The times we don't know where you are, what you're doing, is a fear and pain I can never explain to another person, how much it aches inside believing I may never see you again. I cannot bear a life without you. I tell you often what a bright future I see for you ... Sometimes it is those who experience the most pain, the pain I see you go through, who get past it and do the greatest things. Please accept the help we are offering you. I love you very much."

After the intervention, Chantel agreed to go into treatment immediately.

Oprah had words of encouragement for Chantel. "There is a calling on your life that is bigger than you know, and it's certainly bigger than methamphetamine," Oprah says. "You are not your past. You are not all the things that have happened to you. You are the possibility of what can be. This is not going to be an easy journey for you. But you are going to represent to all the world that says it can't be done. You are going to represent the power that shows it can be done."

Chantel left The Oprah Winfrey Show with Janice Styer, a treatment counselor from the Caron Foundation, an inpatient treatment center in Pennsylvania where thousands of people have turned their lives around.

Oprah had words of encouragement for Chantel. "There is a calling on your life that is bigger than you know, and it's certainly bigger than methamphetamine," Oprah says. "You are not your past. You are not all the things that have happened to you. You are the possibility of what can be. This is not going to be an easy journey for you. But you are going to represent to all the world that says it can't be done. You are going to represent the power that shows it can be done."

Chantel left The Oprah Winfrey Show with Janice Styer, a treatment counselor from the Caron Foundation, an inpatient treatment center in Pennsylvania where thousands of people have turned their lives around.

Sara is a young suburban Minnesota mother who got hooked on this highly addictive and deadly drug. "I was raised with morals and values," Sara says. "I couldn't have asked for better parents. I've always wanted to go to school for law enforcement. I was first runner-up in the Miss Minneapolis beauty pageant. I had a fairy-tale wedding. I had a beautiful little girl…I look in the mirror and [say], 'Who is this person?'"

Sara is broke and living with her parents. In three years, Sara has lost her car, her job, her house and her marriage because of her addiction to crystal meth. Sara is also in trouble with the law and rarely passes her mandatory drug tests, which is how she lost custody of her daughter, Madison.

Sara is broke and living with her parents. In three years, Sara has lost her car, her job, her house and her marriage because of her addiction to crystal meth. Sara is also in trouble with the law and rarely passes her mandatory drug tests, which is how she lost custody of her daughter, Madison.

Losing her little girl wasn't enough to make Sara hit rock bottom. "I thought when I lost my daughter over two years ago it would be enough for me to stop using and I'm going on almost three years now and I'm still using."

Sara's parents fear for her life. They attempt to control her drug use, failing time and time again. "I know they're trying to help," Sara says. "And I know they want the best for me but all's they're doing is making me go out and just want to get high more."

Her family was finally ready to confront Sara in a secretly planned intervention. Her father gave her the ultimatum—"If you're not willing to take place in this recovery process today, you need to know you will need to find a new place to live"—and Sara stormed out of the house to get high.

Sara's parents fear for her life. They attempt to control her drug use, failing time and time again. "I know they're trying to help," Sara says. "And I know they want the best for me but all's they're doing is making me go out and just want to get high more."

Her family was finally ready to confront Sara in a secretly planned intervention. Her father gave her the ultimatum—"If you're not willing to take place in this recovery process today, you need to know you will need to find a new place to live"—and Sara stormed out of the house to get high.

Sara did agree to go to treatment after her intervention. She's been clean for four months.

"My addiction is always sitting right here on my shoulder and it's always calling my name," Sara says. "It's waiting for me to slip up so it can grab me again. And that's why I talk to all my friends back out in California [where she went for counseling], all the counselors, I go to my meetings, I go to church, I'm talking to my parents instead of isolating. I'm letting them know what's making me upset, what's making me angry so we can work through it because I remember a lot of things that I would go get high over."

"My addiction is always sitting right here on my shoulder and it's always calling my name," Sara says. "It's waiting for me to slip up so it can grab me again. And that's why I talk to all my friends back out in California [where she went for counseling], all the counselors, I go to my meetings, I go to church, I'm talking to my parents instead of isolating. I'm letting them know what's making me upset, what's making me angry so we can work through it because I remember a lot of things that I would go get high over."

Now that she's clean, Sara realizes what she put her family through. Sara's father, John, painfully admits that there were times while Sara was addicted that he wished Sara would die. "I wished that she would have died to stop her pain," John says. "Then at least I would have known that she was safe and where she was at."

Sara was so consumed by her addiction, she thought that by agreeing to have that part of her life documented by A&E's Intervention, she would gain sympathy for her addiction. "I was wanting my parents to see just what it was like," Sara says. "The ad in the paper said, 'A week in the life of an addict,' so I thought, 'Okay, they can come out, they can film me, everybody in the world can see how painful it is and what I have to go through every day.' I was trying to be a functioning addict. I thought if I got a job, that I could still use and everything would go back to normal."

Sara's parents, Vicki and John, say it was hard for them to be part of A&E's documentary because they had hidden Sara's addiction for so long from friends. "We knew that she was on something, but maybe it was just denial that it was that drug or what drug it was," John says. "It's like having an ugly monster chasing you around in your house," Vicki says.

Sara was so consumed by her addiction, she thought that by agreeing to have that part of her life documented by A&E's Intervention, she would gain sympathy for her addiction. "I was wanting my parents to see just what it was like," Sara says. "The ad in the paper said, 'A week in the life of an addict,' so I thought, 'Okay, they can come out, they can film me, everybody in the world can see how painful it is and what I have to go through every day.' I was trying to be a functioning addict. I thought if I got a job, that I could still use and everything would go back to normal."

Sara's parents, Vicki and John, say it was hard for them to be part of A&E's documentary because they had hidden Sara's addiction for so long from friends. "We knew that she was on something, but maybe it was just denial that it was that drug or what drug it was," John says. "It's like having an ugly monster chasing you around in your house," Vicki says.

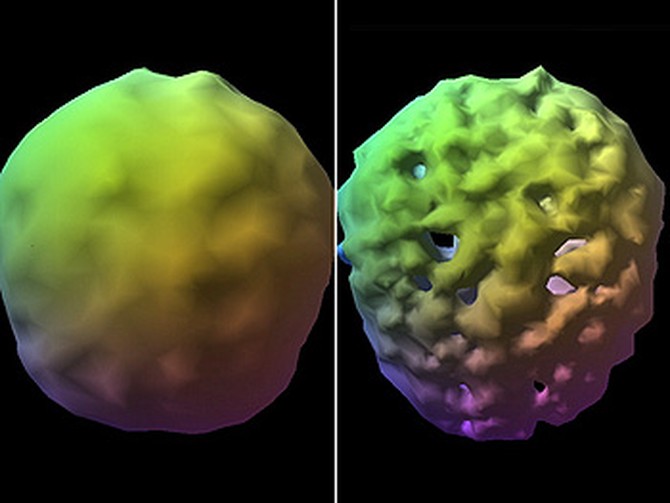

The toxic chemicals in crystal methamphetamine literally eat away brain tissue. The brain on the left is normal and the brain on the right is of a 28-year-old meth user.

"[Crystal meth] literally puts holes in your brain," Debra Jay explains. "Remember how Chantel was talking about her drug addiction? Just like it was nothing. You absolutely lose the ability to learn from past mistakes or to care about anything. And it's not because she's being bad. It's because her brain no longer works. And this can be permanent. That's why it was so important to get her into treatment."

Methamphetamine addicts go days without sleeping or eating and get what Debra Jay calls "a drug-induced anorexia." Malnourished, the body starts eating itself. First fat, then it starts eating muscle…

"[Crystal meth] literally puts holes in your brain," Debra Jay explains. "Remember how Chantel was talking about her drug addiction? Just like it was nothing. You absolutely lose the ability to learn from past mistakes or to care about anything. And it's not because she's being bad. It's because her brain no longer works. And this can be permanent. That's why it was so important to get her into treatment."

Methamphetamine addicts go days without sleeping or eating and get what Debra Jay calls "a drug-induced anorexia." Malnourished, the body starts eating itself. First fat, then it starts eating muscle…

These pictures show the tragic toll that crystal meth can take on a person's physical appearance. Bret King, a jail deputy in Oregon, took these photos of a woman on crystal meth three and a half years apart. (www.co.multnomah.or.us/sheriff/faces_of_meth.htm)

Debra Jay explains the change in the woman's appearance. "First of all, you see all the sores on her face? When you're using crystal meth, they start thinking bugs are under their skin and they start itching all the time. They call it 'crank bugs.' They get obsessive about it and then they started digging holes. They try to dig the bugs out of their skin. You see the holes on her face, if you could see the rest of her body… And then what happens, these sores become infected because typically where they're using these drugs, you cannot believe the filth."

Learn more about crystal meth, interventions and treatment options.

Debra Jay explains the change in the woman's appearance. "First of all, you see all the sores on her face? When you're using crystal meth, they start thinking bugs are under their skin and they start itching all the time. They call it 'crank bugs.' They get obsessive about it and then they started digging holes. They try to dig the bugs out of their skin. You see the holes on her face, if you could see the rest of her body… And then what happens, these sores become infected because typically where they're using these drugs, you cannot believe the filth."

Learn more about crystal meth, interventions and treatment options.

Published 05/13/2005