Getting to Know Gabriel García Márquez

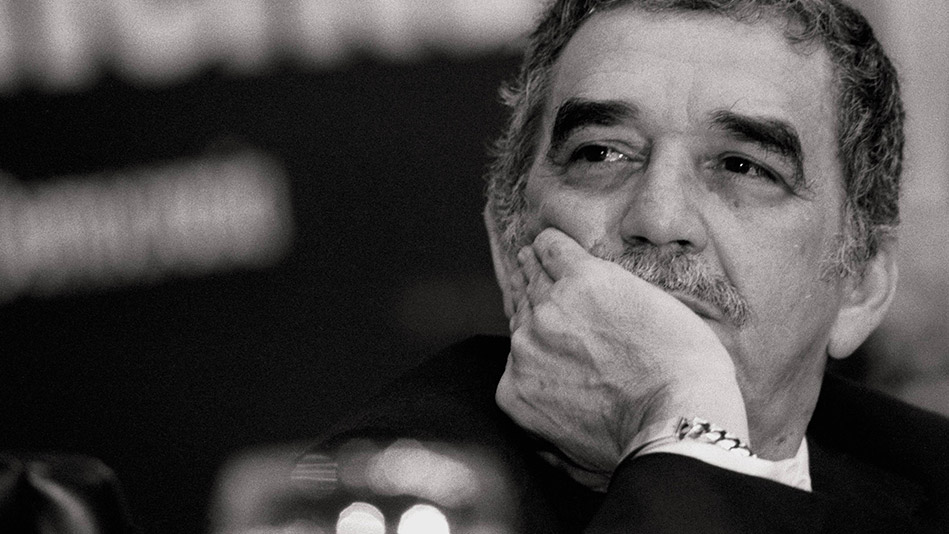

Photo: Paco Junquera/Cover/Getty Images

We were saddened to learn of the passing of one of the greatest writers of our time (whose novels One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera were both selected for Oprah's Book Club). Here we remember him in an interview with scholar Gene Bell-Villada in Mexico City June of 1982.

The following chat with García Márquez took place in his home on Calle Fuego, in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. It was June 1982. His wife, Mercedes—as beautiful and as warmly engaging as rumors say—had opened the front door for me, smiled, and then pointed me toward the inside driveway. "There he is," she said. "There's García Márquez."

Curly-haired and compact (about 5'6"), García Márquez emerged from [his] car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper—his morning writing gear, as it turns out. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, showed up with a shy, taciturn girlfriend. The in-family banter grew lively. In contrast to Gonzalo's Mexican-inflected speech, the novelist's soft voice and dropped s's immediately recalled to me the Caribbean accent of the northern Colombian coast where he had been born and raised.

García Márquez and Gonzalo soon led me across the backyard to the novelist's office, a separate bungalow equipped with special acclimatization (the author still could not take the morning chill in Mexico City), thousands of stereo LPs, various encyclopedias and other reference books, paintings by Latin American artists, and, on the coffee table, a Rubik's Cube. The remaining furnishings included a simple desk and chair and a matched sofa and armchair set, where our interview was held over beers.

Global fame notwithstanding—García Márquez remains a gentle and unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. Throughout our conversation I found it easy to imagine him in the downtown café, sipping drinks with the TV repairman or trading stories with the taco makers. He loves to chat; were it not for the cautious screening process set up by his friends and family, he could easily spend his entire day talking instead of writing.

Gene Bell-Villada: Your One Hundred Years of Solitude is required reading in many history and political science courses in the United States. There's a sense that it's the best general introduction to Latin America. How do you feel about that?

Gabriel García Márquez: I wasn't aware of that fact in particular, but I've had some interesting experiences along the way. On one occasion, a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he'd grown dissatisfied with his methods. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn't have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It's not a scientific thing.

GB-V: There's a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

GGM: That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; I was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of the dead, although it does fit the proportions of the novel. So, instead of hundreds of dead, I upped it to thousands. But it's strange, a Colombian journalist the other day referred in passing to "the thousands who died in the 1928 strike." As my Patriarch says, it doesn't matter if it's true, because with enough time it will be!

GB-V: Some critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

GGM: Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it's not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

GB-V: You're a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

GGM: [He reflects for a moment] It's in my origins; it's my vocation too. It's the life I know best, and I've deliberately cultivated it.

GB-V: With fame, is it hard, keeping up with your popular roots?

GGM: It's tough, but not as much as you'd think. I can go to a local café and at most one person will request an autograph. What's nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they feel good just meeting a Latin American. I never lose sight of the fact that I owe those experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

GB-V: And which of your books is your favorite?

GGM: It's always the latest, so right now it's Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I'm particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Excerpted from Gene Bell-Villada's, casebook on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

The following chat with García Márquez took place in his home on Calle Fuego, in the Pedregal section of Mexico City. It was June 1982. His wife, Mercedes—as beautiful and as warmly engaging as rumors say—had opened the front door for me, smiled, and then pointed me toward the inside driveway. "There he is," she said. "There's García Márquez."

Curly-haired and compact (about 5'6"), García Márquez emerged from [his] car wearing blue one-piece overalls with a front zipper—his morning writing gear, as it turns out. At this point their son Gonzalo, a very Mexican twenty-year-old, showed up with a shy, taciturn girlfriend. The in-family banter grew lively. In contrast to Gonzalo's Mexican-inflected speech, the novelist's soft voice and dropped s's immediately recalled to me the Caribbean accent of the northern Colombian coast where he had been born and raised.

García Márquez and Gonzalo soon led me across the backyard to the novelist's office, a separate bungalow equipped with special acclimatization (the author still could not take the morning chill in Mexico City), thousands of stereo LPs, various encyclopedias and other reference books, paintings by Latin American artists, and, on the coffee table, a Rubik's Cube. The remaining furnishings included a simple desk and chair and a matched sofa and armchair set, where our interview was held over beers.

Global fame notwithstanding—García Márquez remains a gentle and unassuming, indeed an admirably balanced and normal sort of man. Throughout our conversation I found it easy to imagine him in the downtown café, sipping drinks with the TV repairman or trading stories with the taco makers. He loves to chat; were it not for the cautious screening process set up by his friends and family, he could easily spend his entire day talking instead of writing.

The Conversation

Gene Bell-Villada: Your One Hundred Years of Solitude is required reading in many history and political science courses in the United States. There's a sense that it's the best general introduction to Latin America. How do you feel about that?

Gabriel García Márquez: I wasn't aware of that fact in particular, but I've had some interesting experiences along the way. On one occasion, a sociologist from Austin, Texas came to see me because he'd grown dissatisfied with his methods. So he asked me what my own method was. I told him I didn't have a method. All I do is read a lot, think a lot, and rewrite constantly. It's not a scientific thing.

GB-V: There's a very famous strike scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Was it much trouble for you to get it right?

GGM: That sequence sticks closely to the facts of the United Fruit strike of 1928, which dates from my childhood; I was born that year. The only exaggeration is in the number of the dead, although it does fit the proportions of the novel. So, instead of hundreds of dead, I upped it to thousands. But it's strange, a Colombian journalist the other day referred in passing to "the thousands who died in the 1928 strike." As my Patriarch says, it doesn't matter if it's true, because with enough time it will be!

GB-V: Some critics take you to task for not furnishing a more positive vision of Latin America. How do you answer them?

GGM: Yes, that happened to me in Cuba a while ago, where some critics gave One Hundred Years of Solitude high praise and then found fault with it for not offering a solution. I told them it's not the job of novels to furnish solutions.

GB-V: You're a writer with a very intimate knowledge of street life and plebeian ways. What do you owe it to?

GGM: [He reflects for a moment] It's in my origins; it's my vocation too. It's the life I know best, and I've deliberately cultivated it.

GB-V: With fame, is it hard, keeping up with your popular roots?

GGM: It's tough, but not as much as you'd think. I can go to a local café and at most one person will request an autograph. What's nice is that they treat me like one of their own, especially in hotels up in the States, where they feel good just meeting a Latin American. I never lose sight of the fact that I owe those experiences to the many readers of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

GB-V: And which of your books is your favorite?

GGM: It's always the latest, so right now it's Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Of course, there are always differences with readers, and every book is a process. I'm particularly fond of No One Writes to the Colonel, but then that book led me to One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Excerpted from Gene Bell-Villada's, casebook on the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.