The Best Memoirs of a Generation

Remember when we all fell in love with honest, real-life stories that swept us away like our favorite novels? Here's the best of the best from the last 22 years.

By Mary Karr

352 pages; Penguin Classics

Because Karr started a truth-telling revolution.

Karr grew up in East Texas with a hard-drinking father (who played dominoes with his drinking pals in the "Liar's Club") and an enigmatic, alcoholic, mentally ill mother, who is described as Nervous with a capital N. Her dad toiled in the oil fields, while her mother—married a total of seven times—painted, read literature and raged. Karr was raped and sexually assaulted again before the age of 9. Yet, her rendering of a brutal childhood is at times wickedly funny and always movingly illuminating, thanks to kick-ass storytelling and a poet's ear. Published in 1995, The Liar's Club opened the floodgates for women wanting to tell the whole truth. — Dawn Raffel

352 pages; Penguin Classics

Because Karr started a truth-telling revolution.

Karr grew up in East Texas with a hard-drinking father (who played dominoes with his drinking pals in the "Liar's Club") and an enigmatic, alcoholic, mentally ill mother, who is described as Nervous with a capital N. Her dad toiled in the oil fields, while her mother—married a total of seven times—painted, read literature and raged. Karr was raped and sexually assaulted again before the age of 9. Yet, her rendering of a brutal childhood is at times wickedly funny and always movingly illuminating, thanks to kick-ass storytelling and a poet's ear. Published in 1995, The Liar's Club opened the floodgates for women wanting to tell the whole truth. — Dawn Raffel

By Alison Bechdel

232 pages; Mariner Books

Because she made "comics" serious literature.

Bechdel's graphic memoir intertwines the story of her tormented, closeted gay father, who ran a funeral parlor and favored teenage boys, along with her own coming-of-age as a lesbian. Her father's life ended in suicide, and in this raw, honest story, she grapples with their complicated relationship and the toll his secrets took on their family. Moving and profoundly original. — Dawn Raffel

232 pages; Mariner Books

Because she made "comics" serious literature.

Bechdel's graphic memoir intertwines the story of her tormented, closeted gay father, who ran a funeral parlor and favored teenage boys, along with her own coming-of-age as a lesbian. Her father's life ended in suicide, and in this raw, honest story, she grapples with their complicated relationship and the toll his secrets took on their family. Moving and profoundly original. — Dawn Raffel

By Cheryl Strayed

336 pages; Knopf

Because this might be the most cathartic 1,100-mile road trip you'll vicariously take.

At age 26, Cheryl Strayed was, by her own admission, a total mess. Her beloved mother had just died; she'd broken up her young marriage; she was dating a junkie and was well on her way to becoming one herself. But Strayed—who adopted that name because it fit her behavior so well—righted herself by setting out to hike up the Pacific Crest Trail, from the Mojave Desert to northernmost Oregon. How she did it, and what she learned about life, love and survival of the emotional and physical sort, is the subject of her moving memoir. — Sara Nelson

336 pages; Knopf

Because this might be the most cathartic 1,100-mile road trip you'll vicariously take.

At age 26, Cheryl Strayed was, by her own admission, a total mess. Her beloved mother had just died; she'd broken up her young marriage; she was dating a junkie and was well on her way to becoming one herself. But Strayed—who adopted that name because it fit her behavior so well—righted herself by setting out to hike up the Pacific Crest Trail, from the Mojave Desert to northernmost Oregon. How she did it, and what she learned about life, love and survival of the emotional and physical sort, is the subject of her moving memoir. — Sara Nelson

By David Carr

400 pages; Simon & Schuster

Because no one has investigated addiction with this kind of bravery.

The late David Carr, a columnist for The New York Times, lost years of his life to drug addiction and later became an alcoholic. To write this memoir, he spent three years using his fine-tuned journalistic tools to uncover his past, conducting 60 interviews in order to reconstruct the parts of his life he couldn't rightly remember, including a night that ended in a showdown with a pistol. — Dawn Raffel

400 pages; Simon & Schuster

Because no one has investigated addiction with this kind of bravery.

The late David Carr, a columnist for The New York Times, lost years of his life to drug addiction and later became an alcoholic. To write this memoir, he spent three years using his fine-tuned journalistic tools to uncover his past, conducting 60 interviews in order to reconstruct the parts of his life he couldn't rightly remember, including a night that ended in a showdown with a pistol. — Dawn Raffel

By Elizabeth Gilbert

352 pages; Riverhead Books

Because she empowered millions of us to re-examine what we want out of life.

After a scorching divorce, 30-something Elizabeth Gilbert set out on a yearlong journey through Italy, India and Indonesia. Culinary delights, rigorous spiritual searching and exhilarating romance (in that order) were all in store. Eleven years after the book's publication, we're still talking about Gilbert's adventures in self-discovery—and our own—maybe due to ideas like this one. "People think a soul mate is your perfect fit, and that's what everyone wants," she writes. "But a true soul mate is a mirror, the person who shows you everything that's holding you back, the person who brings you to your own attention so you can change your life." — Dawn Raffel

352 pages; Riverhead Books

Because she empowered millions of us to re-examine what we want out of life.

After a scorching divorce, 30-something Elizabeth Gilbert set out on a yearlong journey through Italy, India and Indonesia. Culinary delights, rigorous spiritual searching and exhilarating romance (in that order) were all in store. Eleven years after the book's publication, we're still talking about Gilbert's adventures in self-discovery—and our own—maybe due to ideas like this one. "People think a soul mate is your perfect fit, and that's what everyone wants," she writes. "But a true soul mate is a mirror, the person who shows you everything that's holding you back, the person who brings you to your own attention so you can change your life." — Dawn Raffel

By Ta-Nehisi Coates

240 pages; Spiegel & Grau

Because there are great dads, and then there are great dads like this...

The lyrically gifted Coates recalls growing up black in Baltimore in the '80s—that is, in the age of crack. He movingly portrays his father, a man who had seven kids by four women, was involved with the Black Panthers, loved foreign films and literature, ran a press from his basement, and was fiercely determined to keep his sons off the streets and on the path to Howard University (referred to as Mecca). "Dad wanted me present to everything, my entire neurology cocked," Coates writes. This resonant story of race and coming-of-age is proof his father succeeded. — Dawn Raffel

240 pages; Spiegel & Grau

Because there are great dads, and then there are great dads like this...

The lyrically gifted Coates recalls growing up black in Baltimore in the '80s—that is, in the age of crack. He movingly portrays his father, a man who had seven kids by four women, was involved with the Black Panthers, loved foreign films and literature, ran a press from his basement, and was fiercely determined to keep his sons off the streets and on the path to Howard University (referred to as Mecca). "Dad wanted me present to everything, my entire neurology cocked," Coates writes. This resonant story of race and coming-of-age is proof his father succeeded. — Dawn Raffel

By Susanna Kaysen

192 pages; Vintage

Because she made it okay to talk about mental illness.

Kaysen was only 18, and depressed, when a doctor who'd met her just once sent her to a psychiatric hospital. The year was 1967, and she spent the next two years there. In her memoir, she lifts the shade on the hidden world of the ward for young women. Some of the patients she befriended were seriously mentally ill, others seemed sane but slid into madness, and one tragically committed suicide. With humor and humanity, Kaysen asks us to consider what's "normal," and how we come to terms with the struggles that are part of every life. — Dawn Raffel

192 pages; Vintage

Because she made it okay to talk about mental illness.

Kaysen was only 18, and depressed, when a doctor who'd met her just once sent her to a psychiatric hospital. The year was 1967, and she spent the next two years there. In her memoir, she lifts the shade on the hidden world of the ward for young women. Some of the patients she befriended were seriously mentally ill, others seemed sane but slid into madness, and one tragically committed suicide. With humor and humanity, Kaysen asks us to consider what's "normal," and how we come to terms with the struggles that are part of every life. — Dawn Raffel

By Dave Eggers

437 pages; Vintage

Because it actually lives up to its title.

Eggers lost his father to lung cancer and his mother to stomach cancer one month apart when he was in his 20s, and it fell to him to take care of his 8-year-old brother, Toph. Although Eggers is famous for his big, bold style (he subsequently founded McSweeney's Press and the deadpan, high-irony website McSweeney's Internet Tendencies), what makes this memoir stick is its emotional center. He wants what's best for Toph, yet he wants his own youth too. His impulses sometimes conflict, as everyone's do. Underlying it a genuine love. — Dawn Raffel

437 pages; Vintage

Because it actually lives up to its title.

Eggers lost his father to lung cancer and his mother to stomach cancer one month apart when he was in his 20s, and it fell to him to take care of his 8-year-old brother, Toph. Although Eggers is famous for his big, bold style (he subsequently founded McSweeney's Press and the deadpan, high-irony website McSweeney's Internet Tendencies), what makes this memoir stick is its emotional center. He wants what's best for Toph, yet he wants his own youth too. His impulses sometimes conflict, as everyone's do. Underlying it a genuine love. — Dawn Raffel

By Azar Nafisi

400 pages; Random House Trade Paperbacks

Because who knew how much courage it took just to open a book?

Nafisi's memoir eloquently chronicles her experiences in a Thursday morning book club where Iranian women read the forbidden Western classics. While the club opened its members' minds and liberated them to speak freely among themselves, Nafisi's account opened our eyes, showing us the inner world of Iranian women. She powerfully demonstrates why books make a difference—including this one. — Dawn Raffel

400 pages; Random House Trade Paperbacks

Because who knew how much courage it took just to open a book?

Nafisi's memoir eloquently chronicles her experiences in a Thursday morning book club where Iranian women read the forbidden Western classics. While the club opened its members' minds and liberated them to speak freely among themselves, Nafisi's account opened our eyes, showing us the inner world of Iranian women. She powerfully demonstrates why books make a difference—including this one. — Dawn Raffel

By Mindy Kaling

240 pages; Three Rivers Press

Because Kaling is famous—and really kinda just like the rest of us.

Even megastarlets who get to make out with B.J. Novak and meet the president still fall victim to flaky dates and bridesmaid angst—among the many reasons this essay collection is gut-busting and essential. — Natalie Beach

240 pages; Three Rivers Press

Because Kaling is famous—and really kinda just like the rest of us.

Even megastarlets who get to make out with B.J. Novak and meet the president still fall victim to flaky dates and bridesmaid angst—among the many reasons this essay collection is gut-busting and essential. — Natalie Beach

By Alice Sebold

256 pages; Charles Scribner's Sons

Because she invited us to talk frankly about rape.

Sebold shot to literary stardom with her blockbuster novel The Lovely Bones, narrated by a murdered 14-year-old girl. But first, she wrote this memoir about the violence that forever changed her own life. Sebold was viciously raped at the age of 18 (a police officer told her she was "lucky" because she wasn't killed). She not only fought for the rapist's conviction but also boldly spoke out about the aftermath of sexual assault. First published in 1999, Lucky started a necessary conversation that hasn't ended. — Dawn Raffel

256 pages; Charles Scribner's Sons

Because she invited us to talk frankly about rape.

Sebold shot to literary stardom with her blockbuster novel The Lovely Bones, narrated by a murdered 14-year-old girl. But first, she wrote this memoir about the violence that forever changed her own life. Sebold was viciously raped at the age of 18 (a police officer told her she was "lucky" because she wasn't killed). She not only fought for the rapist's conviction but also boldly spoke out about the aftermath of sexual assault. First published in 1999, Lucky started a necessary conversation that hasn't ended. — Dawn Raffel

By Augusten Burroughs

320 pages; Picador

Because we'll never bitch about our childhood again.

When Burroughs was 12, his unstable, divorced mom decided to send him to live with her shrink. Bad idea hardy does this justice. The psychiatrist, who lived with his family and a few other patients, ran a criminally chaotic household in which school skipping, house wrecking, drug use and underage sex were encouraged. Disturbing as his memoir is, Burrough's resilience and razor-sharp humor lift it into surprising transcendence. — Dawn Raffel

320 pages; Picador

Because we'll never bitch about our childhood again.

When Burroughs was 12, his unstable, divorced mom decided to send him to live with her shrink. Bad idea hardy does this justice. The psychiatrist, who lived with his family and a few other patients, ran a criminally chaotic household in which school skipping, house wrecking, drug use and underage sex were encouraged. Disturbing as his memoir is, Burrough's resilience and razor-sharp humor lift it into surprising transcendence. — Dawn Raffel

By Helen Macdonald

288 pages; Grove Press

Because the last stage of grief should be training a goshawk.

In the wake of her father's sudden death, the grieving Macdonald turns to raising a goshawk named Mabel, who becomes her obsession, partner and healer. This stunning memoir grapples with history, death and nature in prose so exquisitely wrought that it approaches poetry. By the end, the author finds herself transported and, against all hope, hopeful. — Dotun Akintoye

288 pages; Grove Press

Because the last stage of grief should be training a goshawk.

In the wake of her father's sudden death, the grieving Macdonald turns to raising a goshawk named Mabel, who becomes her obsession, partner and healer. This stunning memoir grapples with history, death and nature in prose so exquisitely wrought that it approaches poetry. By the end, the author finds herself transported and, against all hope, hopeful. — Dotun Akintoye

By Patti Smith

320 pages; Ecco

Because this badass rocker is also a brilliant writer.

Smith's chronicle of her relationship with transgressive photographer Robert Mapplethorpe captures not only the youth of two boundary-breaking artists but also the soul of an era. It's about sex, drugs, subversive poetry, hot jazz and rock 'n' roll in the '70s—a time when danger and excitement crackled in the air. It's also about the timelessness of love and forgiveness. — Dawn Raffel

320 pages; Ecco

Because this badass rocker is also a brilliant writer.

Smith's chronicle of her relationship with transgressive photographer Robert Mapplethorpe captures not only the youth of two boundary-breaking artists but also the soul of an era. It's about sex, drugs, subversive poetry, hot jazz and rock 'n' roll in the '70s—a time when danger and excitement crackled in the air. It's also about the timelessness of love and forgiveness. — Dawn Raffel

By Jesmyn Ward

272 pages; Bloomsbury USA

Because Ward's loving remembrance broke our hearts.

In Men We Reaped, a devastating memoir by the National Book Award–winning author of Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward chronicles the lives and deaths of five men she grew up with in a small town on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Her memories of the friends, cousin and brother she lost are ordinary—we see them growing from curious boys to teenage flirts, looking for work and partying, leaving Mississippi and returning again—but her love for them is powerfully visceral, as "large and fierce and elemental as the forest fires that sometimes swept through the woods behind [her] house." It makes the grief all the more palpable when we watch them swallowed by drugs, gun violence, car accidents and suicide. Ward is a vivid, urgent writer, and here she is bearing witness to poverty and racism, the inequality that plagues her community and so many others like it. "There is a great darkness bearing down on our lives," she writes, and her story shines a light on this darkness, reminding us we will never be able to lift it if we do not at least look. — Ruth Baron

272 pages; Bloomsbury USA

Because Ward's loving remembrance broke our hearts.

In Men We Reaped, a devastating memoir by the National Book Award–winning author of Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward chronicles the lives and deaths of five men she grew up with in a small town on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Her memories of the friends, cousin and brother she lost are ordinary—we see them growing from curious boys to teenage flirts, looking for work and partying, leaving Mississippi and returning again—but her love for them is powerfully visceral, as "large and fierce and elemental as the forest fires that sometimes swept through the woods behind [her] house." It makes the grief all the more palpable when we watch them swallowed by drugs, gun violence, car accidents and suicide. Ward is a vivid, urgent writer, and here she is bearing witness to poverty and racism, the inequality that plagues her community and so many others like it. "There is a great darkness bearing down on our lives," she writes, and her story shines a light on this darkness, reminding us we will never be able to lift it if we do not at least look. — Ruth Baron

By Loung Ung

238 pages; Harper Perennial

Because most of us have never known this side of war.

The war in Vietnam and Cambodia was seared into our minds from an American perspective. Loung Ung harrowingly recounts what it was like to live there when the Khmer Rouge stormed Phnom Penh in 1975. Her father was a target because he had been a military police captain. (All previous government officials, professionals and intellectuals were considered enemies.) For 20 months, the family survived as Ung's father hid his identity, braving starvation in the villages where they were sent after fleeing their home. One of the eight children had already died by the time the soldiers took Ung's father; he was never seen again. The rest of the family dispersed, hiding in a nightmarish world of labor camps and land mines. A story of survival and extraordinary courage. — Dawn Raffel

238 pages; Harper Perennial

Because most of us have never known this side of war.

The war in Vietnam and Cambodia was seared into our minds from an American perspective. Loung Ung harrowingly recounts what it was like to live there when the Khmer Rouge stormed Phnom Penh in 1975. Her father was a target because he had been a military police captain. (All previous government officials, professionals and intellectuals were considered enemies.) For 20 months, the family survived as Ung's father hid his identity, braving starvation in the villages where they were sent after fleeing their home. One of the eight children had already died by the time the soldiers took Ung's father; he was never seen again. The rest of the family dispersed, hiding in a nightmarish world of labor camps and land mines. A story of survival and extraordinary courage. — Dawn Raffel

By Joan Didion

227 pages; Vintage

Because one of our coolest thinkers lost her cool.

At the end of 2003, Didion's husband and partner of 40 years, the writer John Gregory Dunne, died of a heart attack. At the same time their only daughter, Quintana, was comatose in a hospital, having suffered septic shock (she died in 2015). Here, Didion, whose penetrating insights, like those in the modern classic Slouching Towards Bethlehem, had already made her an iconic writer, wrangles with death, including the denial (magical thinking) that first allows her to believe that her husband will soon walk through the door. Her journey through grief is also a crystalline tribute to a marriage. — Dawn Raffel

227 pages; Vintage

Because one of our coolest thinkers lost her cool.

At the end of 2003, Didion's husband and partner of 40 years, the writer John Gregory Dunne, died of a heart attack. At the same time their only daughter, Quintana, was comatose in a hospital, having suffered septic shock (she died in 2015). Here, Didion, whose penetrating insights, like those in the modern classic Slouching Towards Bethlehem, had already made her an iconic writer, wrangles with death, including the denial (magical thinking) that first allows her to believe that her husband will soon walk through the door. Her journey through grief is also a crystalline tribute to a marriage. — Dawn Raffel

By Jeannette Walls

288 pages; Scribner

Because she captivated us with the first sentence and never let us go.

"I was sitting in a taxi, wondering if I had overdressed for the evening, when I looked out the window and saw Mom rooting through a Dumpster," Walls begins. In this searing memoir, she relates her hardscrabble childhood with two eccentric—and deteriorating—parents. The family lived like nomads and, later, in poverty as their father drank and their mother fell deeper into dysfunction. Walls managed to escape a desperate situation with her kindness, humor and generosity of spirit intact. — Dawn Raffel

288 pages; Scribner

Because she captivated us with the first sentence and never let us go.

"I was sitting in a taxi, wondering if I had overdressed for the evening, when I looked out the window and saw Mom rooting through a Dumpster," Walls begins. In this searing memoir, she relates her hardscrabble childhood with two eccentric—and deteriorating—parents. The family lived like nomads and, later, in poverty as their father drank and their mother fell deeper into dysfunction. Walls managed to escape a desperate situation with her kindness, humor and generosity of spirit intact. — Dawn Raffel

By Frank McCourt

364 pages; Scribner

Because he was an Irish alchemist.

In a kind of magic trick, Frank McCourt transformed a miserable childhood in the slums of Limerick, Ireland, into a wise, funny and luminous memoir. You wonder how he survived. At least part of the answer must be storytelling. — Dawn Raffel

364 pages; Scribner

Because he was an Irish alchemist.

In a kind of magic trick, Frank McCourt transformed a miserable childhood in the slums of Limerick, Ireland, into a wise, funny and luminous memoir. You wonder how he survived. At least part of the answer must be storytelling. — Dawn Raffel

By David Sedaris

272 pages; Back Bay Books

Because he makes us laugh our asses off.

One of our funniest living writers struck gold in this collection of short autobiographical essays. The title piece hilariously chronicles his less-than-successful efforts to master French while living in Paris. He also skewers his manager dad, his quirky mom, his brother ("the Rooster") and the annoyances of modern life. With his keen eye and sharp wit, he's been compared to everyone from Garrison Keillor to Dorothy Parker, but he has a talent and voice all his own. — Dawn Raffel

272 pages; Back Bay Books

Because he makes us laugh our asses off.

One of our funniest living writers struck gold in this collection of short autobiographical essays. The title piece hilariously chronicles his less-than-successful efforts to master French while living in Paris. He also skewers his manager dad, his quirky mom, his brother ("the Rooster") and the annoyances of modern life. With his keen eye and sharp wit, he's been compared to everyone from Garrison Keillor to Dorothy Parker, but he has a talent and voice all his own. — Dawn Raffel

By James McBride

295 pages; Riverhead

Because this is one great mom.

McBride's mother, Ruth, was born Rachel, the daughter of a Polish Orthodox Jewish rabbi. She left her family, married a black Baptist minister and converted—all things that simply were not done. Remarkably, she battled racism, poverty, isolation and criticism to raise 12 successful children, including one who became an extraordinary author. — Dawn Raffel

295 pages; Riverhead

Because this is one great mom.

McBride's mother, Ruth, was born Rachel, the daughter of a Polish Orthodox Jewish rabbi. She left her family, married a black Baptist minister and converted—all things that simply were not done. Remarkably, she battled racism, poverty, isolation and criticism to raise 12 successful children, including one who became an extraordinary author. — Dawn Raffel

By Maya Angelou

224 pages; Random House

Because her wisdom never, ever dims.

The late Dr. Maya Angelou shot to international acclaim in 1969 with the publication of her first memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. In her seventh and final autobiography, Mom & Me & Mom, published the year before her death, she revisited her relationship with her mother, the formidable Vivian Baxter. Although tough-as-nails Vivian sent Maya away to Stamps, Arkansas, to live with her grandmother when she was 3, the two powerfully reconciled when Maya was a teenager. "Sit down, I have something to say" was Vivian's trademark line. A strong teacher, advocate, sometime adversary and always mentor, Vivian told her young, struggling daughter, "Baby, I've been thinking and now I am sure. You are the greatest woman I've ever met." — Dawn Raffel

224 pages; Random House

Because her wisdom never, ever dims.

The late Dr. Maya Angelou shot to international acclaim in 1969 with the publication of her first memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. In her seventh and final autobiography, Mom & Me & Mom, published the year before her death, she revisited her relationship with her mother, the formidable Vivian Baxter. Although tough-as-nails Vivian sent Maya away to Stamps, Arkansas, to live with her grandmother when she was 3, the two powerfully reconciled when Maya was a teenager. "Sit down, I have something to say" was Vivian's trademark line. A strong teacher, advocate, sometime adversary and always mentor, Vivian told her young, struggling daughter, "Baby, I've been thinking and now I am sure. You are the greatest woman I've ever met." — Dawn Raffel

By Jean-Dominique Bauby and Jeremy Leggatt

131 pages; Vintage Books

Because Bauby wrote by blinking his left eye.

"Something like a giant invisible cocoon holds my whole body prisoner," Bauby writes. At 45, he was the editor-in-chief of French Elle, immersed in the glamour of a successful career, when he suffered a catastrophic "cerebrovascular accident." His condition, akin to a massive stroke, left him with locked-in syndrome: completely paralyzed, confined to a rehab facility and able to communicate only by blinking his one functioning eye. He composed this book in his head, then painstakingly "dictated" it to a friend who recited the alphabet letter by letter, waiting for each confirming blink. Bauby pulls no punches in describing the horror of his situation, from embarrassed, eye-averting visitors to the humiliation of not being able to do even the simplest tasks for himself. Yet, there is light. "My mind takes flight like a butterfly," he writes, recalling everything from the redolent pleasures of food to a long-ago day at the races. A moving testament to the resilience of the human spirit. — Dawn Raffel

131 pages; Vintage Books

Because Bauby wrote by blinking his left eye.

"Something like a giant invisible cocoon holds my whole body prisoner," Bauby writes. At 45, he was the editor-in-chief of French Elle, immersed in the glamour of a successful career, when he suffered a catastrophic "cerebrovascular accident." His condition, akin to a massive stroke, left him with locked-in syndrome: completely paralyzed, confined to a rehab facility and able to communicate only by blinking his one functioning eye. He composed this book in his head, then painstakingly "dictated" it to a friend who recited the alphabet letter by letter, waiting for each confirming blink. Bauby pulls no punches in describing the horror of his situation, from embarrassed, eye-averting visitors to the humiliation of not being able to do even the simplest tasks for himself. Yet, there is light. "My mind takes flight like a butterfly," he writes, recalling everything from the redolent pleasures of food to a long-ago day at the races. A moving testament to the resilience of the human spirit. — Dawn Raffel

By Lucy Grealy

256 pages; Mariner Books

Because she redefined beauty for all of us.

Grealy was 9 years old when she was diagnosed with a rare and deadly cancer. Saving her life required two and a half years of chemo, radiation and the removal of a third of her jaw—and it was the aftermath of this last measure that proved most harrowing. As one reconstructive surgery followed another, she was cruelly taunted about her face, which remained disfigured. Being "ugly" in a culture that seemed to value a woman's beauty above all else made her question her very identity. Her lyrical, witty, unvarnished memoir forces us to look not only at her but also, deeply, at ourselves. — Dawn Raffel

256 pages; Mariner Books

Because she redefined beauty for all of us.

Grealy was 9 years old when she was diagnosed with a rare and deadly cancer. Saving her life required two and a half years of chemo, radiation and the removal of a third of her jaw—and it was the aftermath of this last measure that proved most harrowing. As one reconstructive surgery followed another, she was cruelly taunted about her face, which remained disfigured. Being "ugly" in a culture that seemed to value a woman's beauty above all else made her question her very identity. Her lyrical, witty, unvarnished memoir forces us to look not only at her but also, deeply, at ourselves. — Dawn Raffel

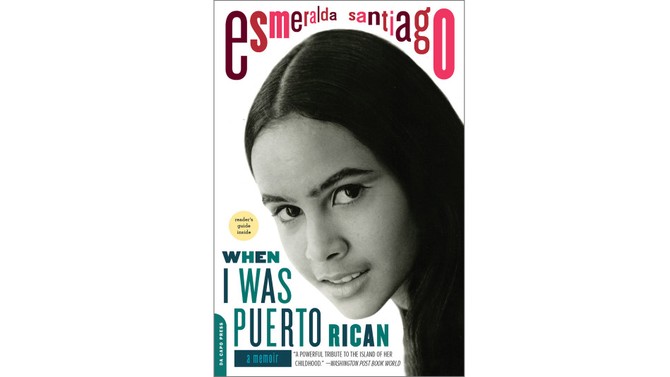

By Esmeralda Santiago

278 pages; Da Capo Press

Because we fell in love with her large, loud, wonderful family.

Santiago recalls the sensuous tastes, sounds and traditions of her early childhood in rural Puerto Rico, followed by her move with her mother, Mami, and six siblings to Brooklyn. Soon there were 11 children and the family depended on welfare; Esmeralda, as the oldest, served as her mother's translator. She portrays impoverished people as people, not statistics, and we see her pride in her heritage, as well as the inevitable culture clashes. She eventually graduated with honors from Harvard University, wrote her best-selling memoir (the first in a trilogy) and became a critically acclaimed novelist—a stylist with the grace to inspire others. — Dawn Raffel

278 pages; Da Capo Press

Because we fell in love with her large, loud, wonderful family.

Santiago recalls the sensuous tastes, sounds and traditions of her early childhood in rural Puerto Rico, followed by her move with her mother, Mami, and six siblings to Brooklyn. Soon there were 11 children and the family depended on welfare; Esmeralda, as the oldest, served as her mother's translator. She portrays impoverished people as people, not statistics, and we see her pride in her heritage, as well as the inevitable culture clashes. She eventually graduated with honors from Harvard University, wrote her best-selling memoir (the first in a trilogy) and became a critically acclaimed novelist—a stylist with the grace to inspire others. — Dawn Raffel

Published 09/13/2017