The Book That Proves We're More Connected Than We Know

One writer channels the rage of a generation.

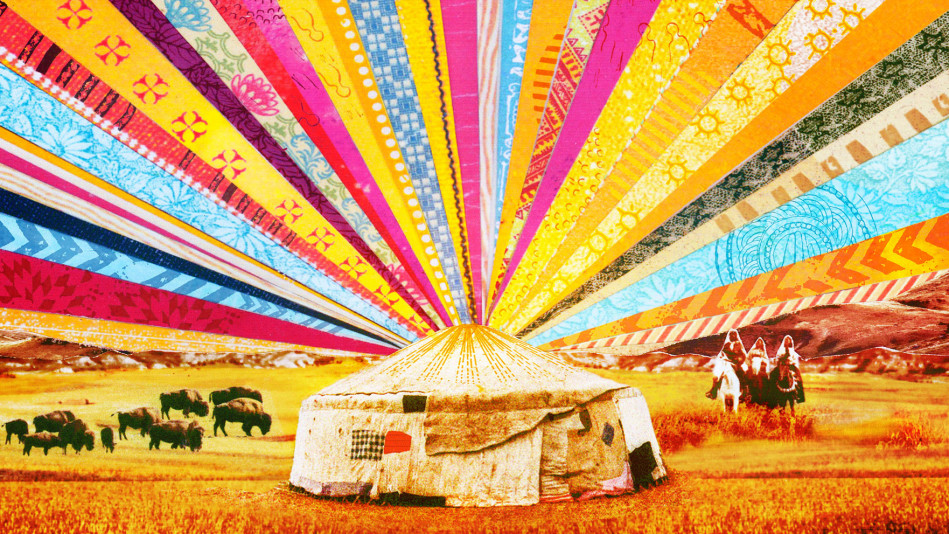

Illustration: Martin O'Neill

"The belief that we can be done with our past is a myth,” writes memoirist Alexandra Fuller in her elegiac first novel, Quiet Until the Thaw.

The notion at the heart of Fuller’s portrait of one Native American family is the way all our ancestors and “the energies of their great passions hang in the air forever...awash in the universe.” Her protagonists wrestle with the suffering of previous generations and with their own particular trials—a woman raising two boys long after her maternal instincts and hope have deserted her, motherless children sent from the reservation to a Catholic boarding school amid pedophile priests. And there’s a larger point: Until all of us fully reckon with a history that includes the genocide of the American Indian, we remain disconnected from one another, unable to comprehend that “everything is related to the existence of all.”

Rick Overlooking Horse and You Choose Watson—members of the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota—are cousins raised on stories of Custer’s Last Stand and how one day “the White Man will succumb to the dark,” tales their grandmother Mina tells night after night until they fall asleep. Overlooking Horse channels their proud and painful legacy into strengths that anchor him, becoming a tribal elder, while Watson embarks on a different path, exploiting his own people, dealing drugs, and landing in jail. Whether he can find redemption as a man who “ain’t done a real, whole good thing in my life” is one of the novel’s central questions. Will he—can we—find “the way out of the dark”?

What inspired Fuller, a white woman who grew up in Zimbabwe (as she recounted in her memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight) and now lives in a yurt, to write a novel so outside her own experience? O books editor Leigh Haber asked.

Leigh Haber: What drew you to this story?

Alexandra Fuller: In 2011, I spent time reporting from the reservation that is the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre. A profound sense of sorrow and compassion grew in me. It led me to want to create a narrative that didn’t look at Native American characters as “the other”—people we define by their ethnicity. I wanted readers to recognize themselves in Overlooking Horse, You Choose, and Mina and not think: Ah, they’re Indians. They’re not like me. Yes, as an oppressed people American Indians have this epic burden, but first and foremost they’re human: sometimes a mess, sometimes funny or sad, at times very wise, and other times not wise at all—a lot like me.

LH: Were you worried others would find it presumptuous that you were writing from the point of view of Native Americans?

AF: I worried about that, yes. I didn’t want to appropriate someone else’s experience. But growing up in Zimbabwe, I was a witness to colonization, to apartheid. What I saw on the rez was familiar. I decided if I stopped worrying about my identity and wrote what I knew to be true, I could make an honest attempt to communicate something powerful. I know the book won’t change the plight and trajectory of what it means to be an American Indian in 2017. But what it might do, I hope, is show what an artificial construct that wall between us and the other is.

LH: When you began the novel, the main character was a woman named LaDasha. Now we don’t meet her until part 2. What changed?

AF: I’d made a reasonable start on the book, and then my father died. I hadn’t seen it coming, and it undid me. LaDasha receded. And Overlooking Horse just took over the page. If Overlooking Horse had been an Englishman who decided to move to middle-of-nowhere Rhodesia, that would have been my dad, a man of few words, but they all counted. I wrote my way out of grief. That’s the advantage of being a writer: No matter what happens, as long as you survive it, it goes into the work.

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah's Book Club Newsletter!

The notion at the heart of Fuller’s portrait of one Native American family is the way all our ancestors and “the energies of their great passions hang in the air forever...awash in the universe.” Her protagonists wrestle with the suffering of previous generations and with their own particular trials—a woman raising two boys long after her maternal instincts and hope have deserted her, motherless children sent from the reservation to a Catholic boarding school amid pedophile priests. And there’s a larger point: Until all of us fully reckon with a history that includes the genocide of the American Indian, we remain disconnected from one another, unable to comprehend that “everything is related to the existence of all.”

Rick Overlooking Horse and You Choose Watson—members of the Oglala Lakota Nation of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota—are cousins raised on stories of Custer’s Last Stand and how one day “the White Man will succumb to the dark,” tales their grandmother Mina tells night after night until they fall asleep. Overlooking Horse channels their proud and painful legacy into strengths that anchor him, becoming a tribal elder, while Watson embarks on a different path, exploiting his own people, dealing drugs, and landing in jail. Whether he can find redemption as a man who “ain’t done a real, whole good thing in my life” is one of the novel’s central questions. Will he—can we—find “the way out of the dark”?

What inspired Fuller, a white woman who grew up in Zimbabwe (as she recounted in her memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight) and now lives in a yurt, to write a novel so outside her own experience? O books editor Leigh Haber asked.

Leigh Haber: What drew you to this story?

Alexandra Fuller: In 2011, I spent time reporting from the reservation that is the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre. A profound sense of sorrow and compassion grew in me. It led me to want to create a narrative that didn’t look at Native American characters as “the other”—people we define by their ethnicity. I wanted readers to recognize themselves in Overlooking Horse, You Choose, and Mina and not think: Ah, they’re Indians. They’re not like me. Yes, as an oppressed people American Indians have this epic burden, but first and foremost they’re human: sometimes a mess, sometimes funny or sad, at times very wise, and other times not wise at all—a lot like me.

LH: Were you worried others would find it presumptuous that you were writing from the point of view of Native Americans?

AF: I worried about that, yes. I didn’t want to appropriate someone else’s experience. But growing up in Zimbabwe, I was a witness to colonization, to apartheid. What I saw on the rez was familiar. I decided if I stopped worrying about my identity and wrote what I knew to be true, I could make an honest attempt to communicate something powerful. I know the book won’t change the plight and trajectory of what it means to be an American Indian in 2017. But what it might do, I hope, is show what an artificial construct that wall between us and the other is.

LH: When you began the novel, the main character was a woman named LaDasha. Now we don’t meet her until part 2. What changed?

AF: I’d made a reasonable start on the book, and then my father died. I hadn’t seen it coming, and it undid me. LaDasha receded. And Overlooking Horse just took over the page. If Overlooking Horse had been an Englishman who decided to move to middle-of-nowhere Rhodesia, that would have been my dad, a man of few words, but they all counted. I wrote my way out of grief. That’s the advantage of being a writer: No matter what happens, as long as you survive it, it goes into the work.

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah's Book Club Newsletter!