Trevor Noah Tells Oprah What He Learned from His "Gangster" Mom

Oprah talks to small-screen satirist Trevor Noah about trying the impossible.

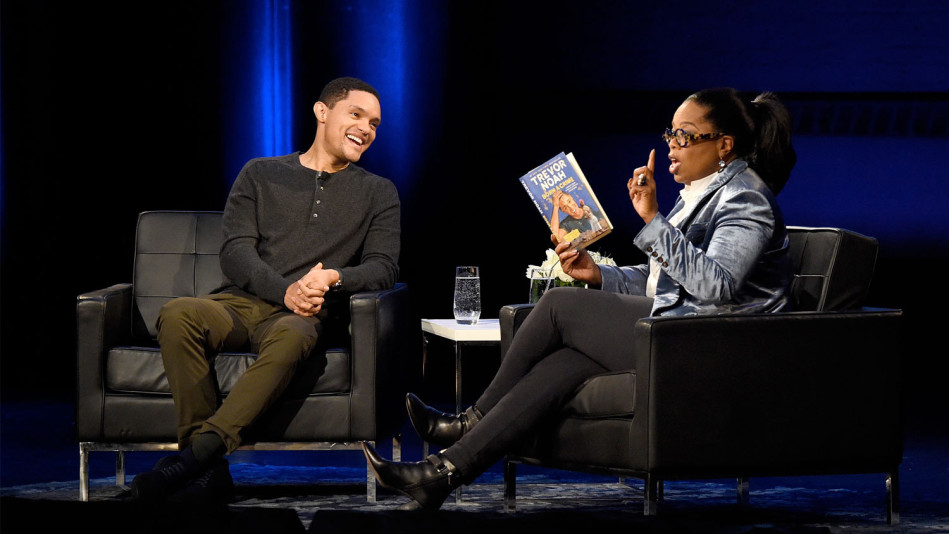

Photo: Kevin Mazur/Getty

Trevor Noah's story is so implausible, it’s almost like a fable: Mixed-race boy grows up in poverty amid the ruthless oppression of apartheid South Africa and ends up behind the desk at one of our most beloved TV institutions. After finishing his soul-stirring 2016 memoir, Born a Crime, I knew I needed to sit down with The Daily Show host to absorb more of his warmth and wisdom. How did the 34-year-old make his way into acting, a career in stand-up, and a coveted late-night role, in which he mocks the outrageousness of our current political climate? With more than a little help from his mother, and the audacity of someone with nothing to lose.

Oprah: I’m so happy you’re here.

Trevor Noah: Thank you so much for having me.

OW: In your book, you told your story with such humor, depth, sincerity, and truth. I’ve never heard of a comedian who grew up in apartheid South Africa under such extreme conditions, then turned that into comedy.

TN: My whole life, comedy has been a tool I’ve used to process pain. And you’ve seen how we live in Soweto.

OW: Yes.

TN: Being poor sucks, but being poor together makes it a lot better. My family had something that sometimes you don’t have when you have too much—the ability to focus on the human beings around you. We had each other, so we laughed.

OW: Your description of apartheid is one of the best I’ve heard. You wrote: It “was a police state, a system of surveillance and laws designed to keep black people under total control.... In America you had the forced removal of the native onto reservations coupled with slavery followed by segregation. Imagine all three of those things happening to the same group of people at the same time.” It was illegal for a European to cohabitate, to have sex...

TN: To have “carnal intercourse” with any person of another race.

OW: So by being mixed race, you were literally born a crime.

TN: Right. Everyone was separated—black and white, and even smaller groups within races. The system was designed to make sure every group was oppressed.

OW: And when you were a little boy, your family had to hide you because you could have been taken away from them.

TN: Yeah, and I didn’t know. As a kid, they’d sometimes tell me to go hide under the bed. In my mind, I had the coolest parents—sometimes I go hide! Only when I was writing the book did my grandmother tell me, “Oh, yes, we hid you because the police would come, and if they found you, they would’ve taken you away.” I was evidence that my parents had broken the law. I was like, “How did I not know this my entire life?” And my grandmother goes, “You never asked.”

OW: Tell the story of the time you went to a new school.

TN: When I went to my first public school, I took a placement test, and they put me in a class with only white kids. I didn’t think that was abnormal until I went to recess and a flood of black children came out of nowhere. They said they were in another class, and I said, “I want to be there.” My teacher said, “That’s not the ‘smart’ class. If you move there, the rest of your life may not go in the direction you want it to.” Well, I chose to go into the black class, and I’m sitting next to Oprah now.

OW: The thing that really got me about your book is that, as one review I read put it, it’s a love letter to your mother.

TN: Completely.

OW: Your mom is a bad-ass warrior woman. She knew it was against the law to be with a white person, and she said, “I’m doing it anyway. I’m gonna have a child and raise him the way I want.”

TN: Most people would have a sign to protest government oppression—my mother had me. In writing this book, I never thought it was about my mom; most of us believe we’re the hero of our own story. But I realized I was always my mother’s sidekick. She stood up at a time when many people were afraid to—when a country was being punished for standing up. She said, “I will live the way I believe,” and she did. She’s the example I live my life by. For me, she’s one of the most gangster human beings.

OW: Oh yeah, your mother is gangster. In the book, you say that “the highest rung of what’s possible is far beyond the world you can see.” You’re the only famous person I’ve interviewed, that I can remember, who grew up poorer than I did. I mean, the fact that we can talk outhouses...

TN: That’s an experience most people cannot understand fully—growing up with an outhouse. It’s a humbling experience. It’s like bungee jumping: I’m glad I did it, but I don’t want to do it again.

OW: How many bathrooms do you have now?

TN: I have three—in America. I’ve got three more back home in South Africa. I’m balling out of control right now!

OW: So I want to know how you ended up on The Daily Show.

TN: That was so surreal. I was in London, touring the world for the first time doing comedy, my lifelong dream. My phone rings with an American number, and a voice says, “Hi, can I speak to Trevor Noah? This is Jon Stewart.” I’m not thinking it’s the Jon Stewart, so I said, “Jon Stewart from...?” And he said, “Oh, sorry, I host The Daily Show in America. I’m a big fan of your comedy.”

OW: Where had he seen you?

TN: On YouTube.

OW: Of course.

TN: He said, “Would you like to come to America, pop into the show, and hang out?” And funnily enough, I said no.

OW: You said no.

TN: I knew I would have to cancel shows, and people had bought tickets to come see me. I don’t take my fans for granted. Jon said, “Well, when you do come to New York, look me up and let’s hang out.” A year and a half later,that’s what I did.

OW: Even though you got the call that some people wait their entire lives for, you had a responsibility to and a respect for your fans. Your mama raised a really good son. So were you surprised when they chose you to host?

TN: I was. Because I come from a world where there was no chance for me. Every chance I’ve taken is the one that’s impossible. But I always say to people, “Why do the possible thing? It’s boring if you succeed. Try the impossible thing.” I thought, I’ll throw my name in, and if I don’t get The Daily Show, I was never meant to get it.

OW: What is your intention with the show? It’s not just about the funny, right?

TN: I think in many ways, it is about the funny for me. But I’ve come to realize, partly by speaking to comedians who’ve been mentors and friends—Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock and Eddie Murphy—that the truth is where the funny lies. For me, in pursuing the funny, I pursue the truth. I’m somebody who loves engaging in the news, discussing ideas, engaging in debate.

OW: Do you feel you’ve hit your stride?

TN: I’m always trying to be better. I’m always unsatisfied. Sometimes the show is a catharsis for me and the people watching. Sometimes it’s a place for us to enjoy laughter. Sometimes it’s a place for us to learn. I’ve realized there is no fixed point. I’m aiming for true north, but it’s shifting with the tide. I’m constantly trying to keep the boat where it needs to go versus where I thought it should go.

OW: And you have to let it guide you. You allow it to take you where it needs to go.

TN: I’m trying.

OW: It’s my great pleasure and delight to meet you.

TN: My honor. Thank you so much.

Oprah: I’m so happy you’re here.

Trevor Noah: Thank you so much for having me.

OW: In your book, you told your story with such humor, depth, sincerity, and truth. I’ve never heard of a comedian who grew up in apartheid South Africa under such extreme conditions, then turned that into comedy.

TN: My whole life, comedy has been a tool I’ve used to process pain. And you’ve seen how we live in Soweto.

OW: Yes.

TN: Being poor sucks, but being poor together makes it a lot better. My family had something that sometimes you don’t have when you have too much—the ability to focus on the human beings around you. We had each other, so we laughed.

OW: Your description of apartheid is one of the best I’ve heard. You wrote: It “was a police state, a system of surveillance and laws designed to keep black people under total control.... In America you had the forced removal of the native onto reservations coupled with slavery followed by segregation. Imagine all three of those things happening to the same group of people at the same time.” It was illegal for a European to cohabitate, to have sex...

TN: To have “carnal intercourse” with any person of another race.

OW: So by being mixed race, you were literally born a crime.

TN: Right. Everyone was separated—black and white, and even smaller groups within races. The system was designed to make sure every group was oppressed.

OW: And when you were a little boy, your family had to hide you because you could have been taken away from them.

TN: Yeah, and I didn’t know. As a kid, they’d sometimes tell me to go hide under the bed. In my mind, I had the coolest parents—sometimes I go hide! Only when I was writing the book did my grandmother tell me, “Oh, yes, we hid you because the police would come, and if they found you, they would’ve taken you away.” I was evidence that my parents had broken the law. I was like, “How did I not know this my entire life?” And my grandmother goes, “You never asked.”

OW: Tell the story of the time you went to a new school.

TN: When I went to my first public school, I took a placement test, and they put me in a class with only white kids. I didn’t think that was abnormal until I went to recess and a flood of black children came out of nowhere. They said they were in another class, and I said, “I want to be there.” My teacher said, “That’s not the ‘smart’ class. If you move there, the rest of your life may not go in the direction you want it to.” Well, I chose to go into the black class, and I’m sitting next to Oprah now.

OW: The thing that really got me about your book is that, as one review I read put it, it’s a love letter to your mother.

TN: Completely.

OW: Your mom is a bad-ass warrior woman. She knew it was against the law to be with a white person, and she said, “I’m doing it anyway. I’m gonna have a child and raise him the way I want.”

TN: Most people would have a sign to protest government oppression—my mother had me. In writing this book, I never thought it was about my mom; most of us believe we’re the hero of our own story. But I realized I was always my mother’s sidekick. She stood up at a time when many people were afraid to—when a country was being punished for standing up. She said, “I will live the way I believe,” and she did. She’s the example I live my life by. For me, she’s one of the most gangster human beings.

OW: Oh yeah, your mother is gangster. In the book, you say that “the highest rung of what’s possible is far beyond the world you can see.” You’re the only famous person I’ve interviewed, that I can remember, who grew up poorer than I did. I mean, the fact that we can talk outhouses...

TN: That’s an experience most people cannot understand fully—growing up with an outhouse. It’s a humbling experience. It’s like bungee jumping: I’m glad I did it, but I don’t want to do it again.

OW: How many bathrooms do you have now?

TN: I have three—in America. I’ve got three more back home in South Africa. I’m balling out of control right now!

OW: So I want to know how you ended up on The Daily Show.

TN: That was so surreal. I was in London, touring the world for the first time doing comedy, my lifelong dream. My phone rings with an American number, and a voice says, “Hi, can I speak to Trevor Noah? This is Jon Stewart.” I’m not thinking it’s the Jon Stewart, so I said, “Jon Stewart from...?” And he said, “Oh, sorry, I host The Daily Show in America. I’m a big fan of your comedy.”

OW: Where had he seen you?

TN: On YouTube.

OW: Of course.

TN: He said, “Would you like to come to America, pop into the show, and hang out?” And funnily enough, I said no.

OW: You said no.

TN: I knew I would have to cancel shows, and people had bought tickets to come see me. I don’t take my fans for granted. Jon said, “Well, when you do come to New York, look me up and let’s hang out.” A year and a half later,that’s what I did.

OW: Even though you got the call that some people wait their entire lives for, you had a responsibility to and a respect for your fans. Your mama raised a really good son. So were you surprised when they chose you to host?

TN: I was. Because I come from a world where there was no chance for me. Every chance I’ve taken is the one that’s impossible. But I always say to people, “Why do the possible thing? It’s boring if you succeed. Try the impossible thing.” I thought, I’ll throw my name in, and if I don’t get The Daily Show, I was never meant to get it.

OW: What is your intention with the show? It’s not just about the funny, right?

TN: I think in many ways, it is about the funny for me. But I’ve come to realize, partly by speaking to comedians who’ve been mentors and friends—Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock and Eddie Murphy—that the truth is where the funny lies. For me, in pursuing the funny, I pursue the truth. I’m somebody who loves engaging in the news, discussing ideas, engaging in debate.

OW: Do you feel you’ve hit your stride?

TN: I’m always trying to be better. I’m always unsatisfied. Sometimes the show is a catharsis for me and the people watching. Sometimes it’s a place for us to enjoy laughter. Sometimes it’s a place for us to learn. I’ve realized there is no fixed point. I’m aiming for true north, but it’s shifting with the tide. I’m constantly trying to keep the boat where it needs to go versus where I thought it should go.

OW: And you have to let it guide you. You allow it to take you where it needs to go.

TN: I’m trying.

OW: It’s my great pleasure and delight to meet you.

TN: My honor. Thank you so much.