How One Little Boy's Letter Saved His Father's Life

The Super Soul Sunday guest and author of Writing My Wrongs on how his son's words changed him from darkness to mindfulness.

Photo: Taeko Koba/Getty Images

The most important letter I ever received in my life came from my son Jay, while I was serving a 19-year-long prison sentence. Jay was around 11 at the time, and I was nearly three years into a four-and-a-half-year stretch in solitary confinement. When the second-shift officer slid a few letters beneath my door, I had no idea how my life was about to change. I swooped the letters up and rifled through them to see who had taken time out of their day to connect with me. There was a letter from a friend who was located at another prison, one from my father and, at last, a letter from my son.

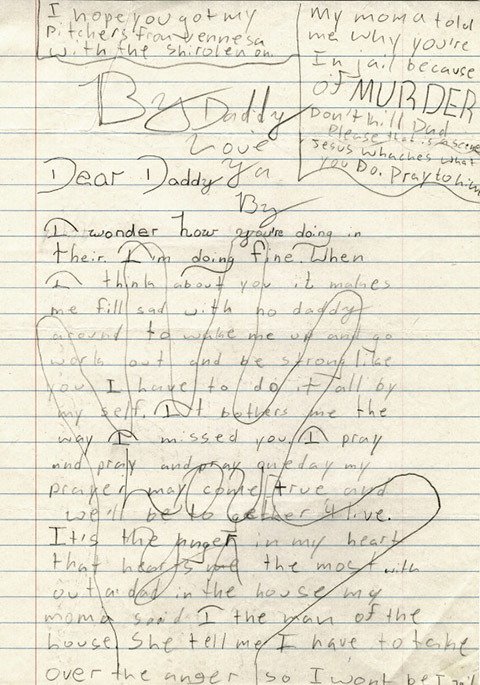

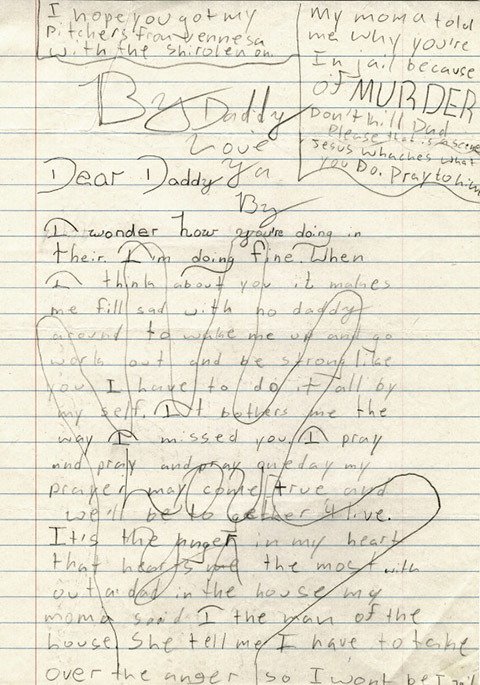

The sight of my son's squiggly handwriting filled me with joy. I hastily read my other letters before I sat down to read my son's. My heart began to sputter when I opened the envelope and read his bold words. In the top right hand corner, in capital letters, he wrote: "MY MOM TOLD ME WHY YOU'RE IN JAIL, BECAUSE OF MURDER! DON'T KILL DAD PLEASE THAT IS A SIN. JESUS WATCHES WHAT YOU DO. PRAY TO HIM."

I stared at the small paragraph for what felt like hours. My body trembled violently as everything inside of me threatened to break in half. It was the first time in my life that I had given any thought to the fact that my son would grow up to see me as a murderer. He was forcing me to examine things about my life that I wished would go quietly away. But his words wouldn't allow me to hide. I stopped reading and thought about something I had read in the prison library. It was a statement Socrates made in Plato's book The Apology: "The unexamined life is not worth living." At that moment, I had to agree. I had not been living, but merely existing. I began to question how I went from wanting to be a doctor to serving out my most promising years for second-degree murder.

From that moment forward, I began an arduous journey. I read every book I could get my hands on, and feverishly journaled on any piece of paper I could find. I learned to let go of the negative thoughts that led to the poor decisions that landed me in prison. I decided that I would no longer think of myself as a prison-yard goon, or a violent street thug. Those negative thoughts had caused me enough heartache and pain and I no longer wanted to live beneath that cloud of darkness.

Little by little, I began replacing these negative thoughts with life-affirming thoughts. I learned to look outside myself, to other people in similar situations. By reading about Nelson Mandela and his 27-year-long fight for freedom, I learned that I could take control of my present—and my future.

I began to recognize what was most important to me and to place things on a scale in terms of what they mean emotionally, physically and spiritually. Being a present father in the lives of my children, and being liberated from my past life, were two of the most important things to me.

I surrounded myself with people who kept me honest. This was the toughest part, and still is. We like for people to tell us what we want to hear, but I'm afraid of those people. I want to hear what I need to hear from a person whose core values I trust. I relied on one of my closest friends in prison, Calvin Evans, who challenged me to grow as a man.

I learned to be mindful of the messages I heard. On a daily basis, there was someone saying that I would never make it out of prison, and I learned to drown out that negative talk. Some days, I listened to artist like Mos Def, or I read books about positive thinking, like As A Man Thinketh, by James Allen, or I wrote to escape into my own world. We take in so much information in our day-to-day lives. A lot of times, we don't stop to challenge that information. All of it is some form of messaging. I am conscious of the music I listen to, of the people I'm with, of what I watch. If you subconsciously listen to music, you may not realize what is feeding your spirit."

Most of all, I learned to meditate and to understand my triggers. Instead of acting like negative thoughts didn't exist, I learned to recognize they were my thoughts, to let them run their cycle then to replace them with positive thoughts. "In life you will have patterns of negative thinking. If you can recognize that in yourself and how it spirals out of control, you can put yourself back on the path."

These changes prepared me for life on the outside, and to go back to the same community where I knew I would encounter negative thinkers and situations. Not a day went by without me reading and writing about positive options, and the things I truly desired in life. The more letters I received from my son, the more focused I became on turning my life around. Before I was released from solitary, I set my days up as if I was going to college. I studied a different subject hourly until midday, and then wrote until the wee hours of the night. When I was released from solitary confinement, I had five more years before I would see freedom. I continued my study and writing habits over that time period. When it was finally time for me to walk out of prison on June 22, 2010, I was prepared in mind, body and soul to start life fresh and to use my voice to make the world a better place.

Shaka Senghor is the author of Writing My Wrongs and three other books. You can find him at ShakaSenghor.com.

Shaka Senghor is the author of Writing My Wrongs and three other books. You can find him at ShakaSenghor.com.

The sight of my son's squiggly handwriting filled me with joy. I hastily read my other letters before I sat down to read my son's. My heart began to sputter when I opened the envelope and read his bold words. In the top right hand corner, in capital letters, he wrote: "MY MOM TOLD ME WHY YOU'RE IN JAIL, BECAUSE OF MURDER! DON'T KILL DAD PLEASE THAT IS A SIN. JESUS WATCHES WHAT YOU DO. PRAY TO HIM."

I stared at the small paragraph for what felt like hours. My body trembled violently as everything inside of me threatened to break in half. It was the first time in my life that I had given any thought to the fact that my son would grow up to see me as a murderer. He was forcing me to examine things about my life that I wished would go quietly away. But his words wouldn't allow me to hide. I stopped reading and thought about something I had read in the prison library. It was a statement Socrates made in Plato's book The Apology: "The unexamined life is not worth living." At that moment, I had to agree. I had not been living, but merely existing. I began to question how I went from wanting to be a doctor to serving out my most promising years for second-degree murder.

From that moment forward, I began an arduous journey. I read every book I could get my hands on, and feverishly journaled on any piece of paper I could find. I learned to let go of the negative thoughts that led to the poor decisions that landed me in prison. I decided that I would no longer think of myself as a prison-yard goon, or a violent street thug. Those negative thoughts had caused me enough heartache and pain and I no longer wanted to live beneath that cloud of darkness.

Little by little, I began replacing these negative thoughts with life-affirming thoughts. I learned to look outside myself, to other people in similar situations. By reading about Nelson Mandela and his 27-year-long fight for freedom, I learned that I could take control of my present—and my future.

I began to recognize what was most important to me and to place things on a scale in terms of what they mean emotionally, physically and spiritually. Being a present father in the lives of my children, and being liberated from my past life, were two of the most important things to me.

I surrounded myself with people who kept me honest. This was the toughest part, and still is. We like for people to tell us what we want to hear, but I'm afraid of those people. I want to hear what I need to hear from a person whose core values I trust. I relied on one of my closest friends in prison, Calvin Evans, who challenged me to grow as a man.

I learned to be mindful of the messages I heard. On a daily basis, there was someone saying that I would never make it out of prison, and I learned to drown out that negative talk. Some days, I listened to artist like Mos Def, or I read books about positive thinking, like As A Man Thinketh, by James Allen, or I wrote to escape into my own world. We take in so much information in our day-to-day lives. A lot of times, we don't stop to challenge that information. All of it is some form of messaging. I am conscious of the music I listen to, of the people I'm with, of what I watch. If you subconsciously listen to music, you may not realize what is feeding your spirit."

Most of all, I learned to meditate and to understand my triggers. Instead of acting like negative thoughts didn't exist, I learned to recognize they were my thoughts, to let them run their cycle then to replace them with positive thoughts. "In life you will have patterns of negative thinking. If you can recognize that in yourself and how it spirals out of control, you can put yourself back on the path."

These changes prepared me for life on the outside, and to go back to the same community where I knew I would encounter negative thinkers and situations. Not a day went by without me reading and writing about positive options, and the things I truly desired in life. The more letters I received from my son, the more focused I became on turning my life around. Before I was released from solitary, I set my days up as if I was going to college. I studied a different subject hourly until midday, and then wrote until the wee hours of the night. When I was released from solitary confinement, I had five more years before I would see freedom. I continued my study and writing habits over that time period. When it was finally time for me to walk out of prison on June 22, 2010, I was prepared in mind, body and soul to start life fresh and to use my voice to make the world a better place.

Shaka Senghor is the author of Writing My Wrongs and three other books. You can find him at ShakaSenghor.com.

Shaka Senghor is the author of Writing My Wrongs and three other books. You can find him at ShakaSenghor.com.