What Nobody Tells You About Painful Regrets

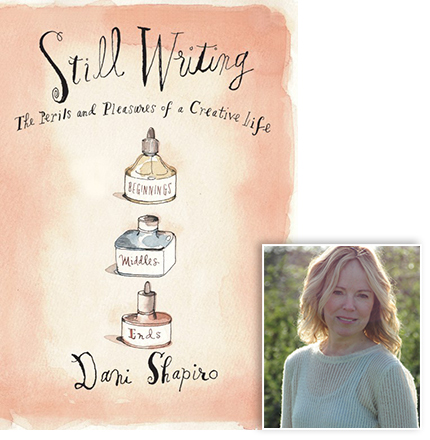

Beating yourself up about the past is one option. The author of Still Writing offers an alternate method of coping with what's behind us—and somehow, still with us.

Photo: Charles Harker/Getty Images

For the past 14 years, I have lived with my husband, son and two dogs in a weather-beaten house on a hill in rural Connecticut. By "rural," I mean that we encounter wild turkeys, foxes, beavers, many deer, opossums and the occasional bear. By "rural," I mean that we don't know our neighbors' names; no one's knocking on our door to borrow a cup of sugar.

We moved to the country when our son was in preschool. We were two very urban people making a decision to live a different kind of life than the one we had planned. We had our reasons. Our son had been very sick as a baby, and we almost lost him. He began to recover right around September of 2001. I held him in my arms as we watched the planes hit the towers, and we made the decision to leave the city the very next day.

Yet, for the first year that we lived in the country, every single day I questioned whether we had made the right move. I was lonely. The tools I had always used to soothe myself—yoga classes, long walks down city streets, impromptu coffees or drinks with girlfriends—were no longer available to me. The new moms I met in Connecticut didn't feel like my kind of women. They did things like ride horses and go hiking after school drop-off. I despaired of ever feeling at home.

Each morning, I opened my door to the sound of...nothing. Rustling leaves. A little baby chipmunk skittering across the porch. The silence was deafening. Had we done the wrong thing?

People asked me all the time: "Don't you ever regret leaving the city?" Friends took bets on how long it would be before we moved back.

In the throes of that unhappy first year—and for several years after—I thought, "Yes, I did regret it." Then I had to dig deeper. I was conflicted. I was full of doubt. I missed a lot of things about the city. I missed the thousands upon thousands of faces. I missed the fact that you could have anything from diapers to Thai food delivered to your door 24 hours a day. I missed the 15-minute manicure. The café where the barista makes a perfect leaf in my macchiato. I missed the elderly ladies pushing their shopping carts down crowded supermarket aisles who had sharper elbows than I did. I missed Strawberry Fields in Central Park and the fountains of Lincoln Center lit up at night.

Still, missing these things was not the same as regretting having left. When I looked around, my son was healthy, and my husband and I had never been closer. It struck me that what I thought was regret was really grief for what was already behind us. Unfortunately, my way of dealing with this loss had been to rely on the world's most toxic phrase: "What if?"

****

At that time, our move to the country was also complicated by my husband's career as a screenwriter. Screenwriters are supposed to live in Los Angeles. Ask anyone. So when we left New York, it would have been reasonable to assume we'd move to L.A. But our son needed several years of physical and occupational therapy after his illness, and I couldn't picture him in the pressure cooker environment of another big city. This meant that my husband would struggle more than your typical struggling screenwriter. He's racked up countless miles making round-trips from coast to coast for meetings that often have led nowhere, and that sometimes were even canceled at the last minute. (It wasn't their fault that he didn't live a 15-minute drive away from all the Hollywood studios, after all.) He's not a regular at the beach parties in Malibu or at dinners high above the Hollywood Hills, where a lot of business gets done. When he's creatively stuck, he grabs his chain saw and cuts down dead tree branches, or hops in the car and drives to the post office to pick up the mail.

I know there have been times when he's wondered whether he would have landed more Hollywood jobs if we had lived there. I have wondered the same thing. When we have gone through moments of financial peril, a cold wind blows past us both. We could have had a very different life had we moved to Los Angeles. Nevertheless, would my last four books have been written without the space and quiet of a country life? Would our marriage have the depth it does without the time we've been able to carve out to be together? We started an international writers' conference because of a chance meeting at a dinner party in Connecticut that has been one of the great pleasures of our family's life. If we had stayed in New York, it simply never would have happened.

As we muddled our way through these challenges, I began to realize that the thing about genuine regret is that it's not a feeling we can isolate from the bigger picture. If we change one thing—say, where we live, who we marry, our career paths, how many kids to have (if any)—we must be willing to change everything. In this way, regret is a bit like envy. I have friends who have certain things in their lives that I don't. Living parents, for instance. I have felt the sting of tears behind my eyes at the family celebrations of others, aware of how much my parents, who died when I was quite young, have missed. How much I have missed. And yet, would I be willing to trade lives? To swap out the whole package for one small piece of it? Would I want my friend's marriage instead of mine? Her kids instead of my own? What about her particular brand of fear and insecurity? What about the health crisis she had last year? We don't get to cherry-pick.

I've had the same reaction when I sense that someone is envious of a particular aspect of my life (my career, say, or my son making the varsity tennis team). "Really?" I feel like asking. "Would you like to live through an infant's dire prognosis? A father's death in a car crash? A mother's death from cancer?"

A few women I know are suffused with regret. It isn't a breeze that blows by—no, it's the very air they breathe. One married the wrong guy, who refused to have children, and they divorced when she was 40. She missed having kids, and she feels it every day: a hole in her being. Another is someone my husband and I privately call Eeyore. Remember that sad-eyed donkey from Winnie the Pooh? Everything for Eeyore is always grim. The grass is greener over there, no matter what. Life is never, ever quite what it should have been.

Now that I've wrestled with it (over and over), here's what I really think: The grass is never greener because we haven't walked barefoot on that grass. We haven't inhaled its essence. We don't know the soil from which it grows. Life is not something that simply happens to us; rather, it's something that we shape, prune, build and order as we move through it.

Of course, shit does happen: illness, heartache, violence, betrayal. We weather our losses, but we don't—we can't—regret them because we had no agency in creating them. We can only regret choices that we make, or choices that we actively don't make. That's why it's so painful. We decided on that path. We set it into motion.

Meanwhile, the parallel lives we live in our heads, the fantasies of what might have been if only we had done things differently, are indeed just fantasies. We can torture ourselves until the end of time, but first, let's make sure that we're looking at the whole picture, and ask ourselves an honest question: If I could go back in time and undo this one choice, what else would I long for and what else would I miss?

We moved to the country when our son was in preschool. We were two very urban people making a decision to live a different kind of life than the one we had planned. We had our reasons. Our son had been very sick as a baby, and we almost lost him. He began to recover right around September of 2001. I held him in my arms as we watched the planes hit the towers, and we made the decision to leave the city the very next day.

Yet, for the first year that we lived in the country, every single day I questioned whether we had made the right move. I was lonely. The tools I had always used to soothe myself—yoga classes, long walks down city streets, impromptu coffees or drinks with girlfriends—were no longer available to me. The new moms I met in Connecticut didn't feel like my kind of women. They did things like ride horses and go hiking after school drop-off. I despaired of ever feeling at home.

Each morning, I opened my door to the sound of...nothing. Rustling leaves. A little baby chipmunk skittering across the porch. The silence was deafening. Had we done the wrong thing?

People asked me all the time: "Don't you ever regret leaving the city?" Friends took bets on how long it would be before we moved back.

In the throes of that unhappy first year—and for several years after—I thought, "Yes, I did regret it." Then I had to dig deeper. I was conflicted. I was full of doubt. I missed a lot of things about the city. I missed the thousands upon thousands of faces. I missed the fact that you could have anything from diapers to Thai food delivered to your door 24 hours a day. I missed the 15-minute manicure. The café where the barista makes a perfect leaf in my macchiato. I missed the elderly ladies pushing their shopping carts down crowded supermarket aisles who had sharper elbows than I did. I missed Strawberry Fields in Central Park and the fountains of Lincoln Center lit up at night.

Still, missing these things was not the same as regretting having left. When I looked around, my son was healthy, and my husband and I had never been closer. It struck me that what I thought was regret was really grief for what was already behind us. Unfortunately, my way of dealing with this loss had been to rely on the world's most toxic phrase: "What if?"

At that time, our move to the country was also complicated by my husband's career as a screenwriter. Screenwriters are supposed to live in Los Angeles. Ask anyone. So when we left New York, it would have been reasonable to assume we'd move to L.A. But our son needed several years of physical and occupational therapy after his illness, and I couldn't picture him in the pressure cooker environment of another big city. This meant that my husband would struggle more than your typical struggling screenwriter. He's racked up countless miles making round-trips from coast to coast for meetings that often have led nowhere, and that sometimes were even canceled at the last minute. (It wasn't their fault that he didn't live a 15-minute drive away from all the Hollywood studios, after all.) He's not a regular at the beach parties in Malibu or at dinners high above the Hollywood Hills, where a lot of business gets done. When he's creatively stuck, he grabs his chain saw and cuts down dead tree branches, or hops in the car and drives to the post office to pick up the mail.

I know there have been times when he's wondered whether he would have landed more Hollywood jobs if we had lived there. I have wondered the same thing. When we have gone through moments of financial peril, a cold wind blows past us both. We could have had a very different life had we moved to Los Angeles. Nevertheless, would my last four books have been written without the space and quiet of a country life? Would our marriage have the depth it does without the time we've been able to carve out to be together? We started an international writers' conference because of a chance meeting at a dinner party in Connecticut that has been one of the great pleasures of our family's life. If we had stayed in New York, it simply never would have happened.

As we muddled our way through these challenges, I began to realize that the thing about genuine regret is that it's not a feeling we can isolate from the bigger picture. If we change one thing—say, where we live, who we marry, our career paths, how many kids to have (if any)—we must be willing to change everything. In this way, regret is a bit like envy. I have friends who have certain things in their lives that I don't. Living parents, for instance. I have felt the sting of tears behind my eyes at the family celebrations of others, aware of how much my parents, who died when I was quite young, have missed. How much I have missed. And yet, would I be willing to trade lives? To swap out the whole package for one small piece of it? Would I want my friend's marriage instead of mine? Her kids instead of my own? What about her particular brand of fear and insecurity? What about the health crisis she had last year? We don't get to cherry-pick.

I've had the same reaction when I sense that someone is envious of a particular aspect of my life (my career, say, or my son making the varsity tennis team). "Really?" I feel like asking. "Would you like to live through an infant's dire prognosis? A father's death in a car crash? A mother's death from cancer?"

A few women I know are suffused with regret. It isn't a breeze that blows by—no, it's the very air they breathe. One married the wrong guy, who refused to have children, and they divorced when she was 40. She missed having kids, and she feels it every day: a hole in her being. Another is someone my husband and I privately call Eeyore. Remember that sad-eyed donkey from Winnie the Pooh? Everything for Eeyore is always grim. The grass is greener over there, no matter what. Life is never, ever quite what it should have been.

Now that I've wrestled with it (over and over), here's what I really think: The grass is never greener because we haven't walked barefoot on that grass. We haven't inhaled its essence. We don't know the soil from which it grows. Life is not something that simply happens to us; rather, it's something that we shape, prune, build and order as we move through it.

Of course, shit does happen: illness, heartache, violence, betrayal. We weather our losses, but we don't—we can't—regret them because we had no agency in creating them. We can only regret choices that we make, or choices that we actively don't make. That's why it's so painful. We decided on that path. We set it into motion.

Meanwhile, the parallel lives we live in our heads, the fantasies of what might have been if only we had done things differently, are indeed just fantasies. We can torture ourselves until the end of time, but first, let's make sure that we're looking at the whole picture, and ask ourselves an honest question: If I could go back in time and undo this one choice, what else would I long for and what else would I miss?

Dani Shapiro is the author of Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life and Devotion, among other books. Find our more about her at DaniShapiro.com.

Dani Shapiro is the author of Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life and Devotion, among other books. Find our more about her at DaniShapiro.com.