This Is What Life Was Like Before the Internet

Sarah Manguso reflects on the pre-internet days when information was hard to come by.

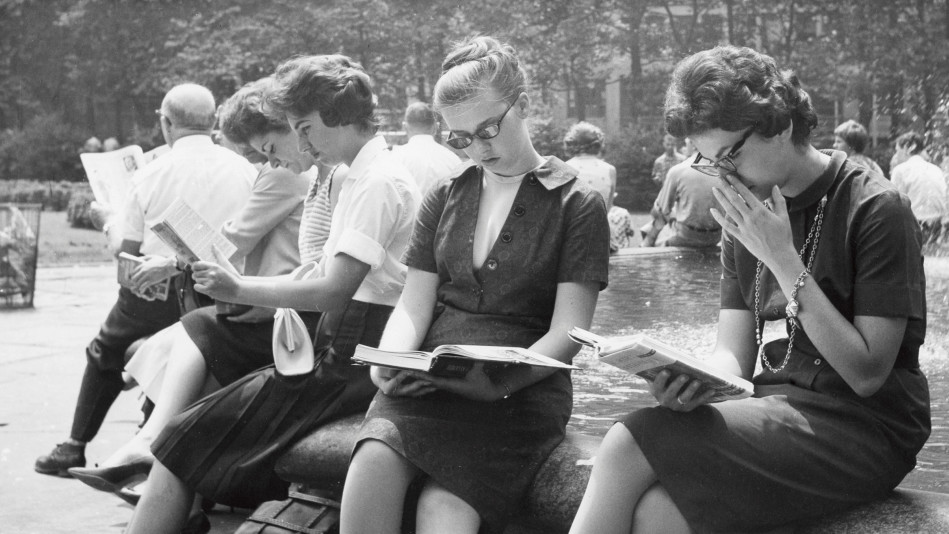

Photo: Popper LTD./ Ullstein Bild Via Getty Images

When I was a teenager visiting Leipzig, Germany, before we had the ability to know anything whenever we wanted to know it, I ate a jam-filled cake topped with ground poppy seeds, some variant of the Berliner. I don't know what it was called. I don't want to. I miss these kinds of mysteries. We used to go about life seldom knowing what would happen or even what had happened. If I'd needed to name that pastry, I could have read cookbooks, asked chefs, written to the Leipzig Chamber of Commerce—but I didn't. That was a once-in-a-lifetime bite.

These days, we can find out in mere moments what thresher sharks eat and whether ladybugs are nocturnal. We're exempt from waiting, denied the chance of surprise. And I'm convinced we are missing out on an essential human experience: not knowing.

It used to be that if I heard a bit of music I couldn't identify, I had to write it down, trying to score it on paper; I still have scraps from the '80s with hasty notations in the shorthand I invented. So many hours of my young life were spent hoping I'd learn the name of a song I'd heard on the radio. Singing fuzzily remembered lyrics for years. Having to be satisfied with that. The attendant heartache was part of the bargain—loving a piece of music didn't mean I got to know everything about it. I had to tolerate yearning. And I came to enjoy it: The answers to these little mysteries felt so beguilingly close, and it was tantalizing to sense them, just out of reach.

Once, in elementary school, we had an assembly about birds of prey. There was a great horned owl, and one of its feathers floated to the floor. After the presentation, I picked it up quickly, before anyone else could. I brought home the white fluff and made a paper envelope for it.

The feather was a prize—but it was also the only way I could keep that experience. There was no way to see that owl again, not really. I might find some small, unsatisfying image in an encyclopedia, but that would have been like looking at that magnificent creature through layers of fog, a photocopy of a photocopy.

My other option was to flip through stacks of National Geographic, hoping to stumble on a full-color photograph. My hometown library kept a room stocked with old issues that students could tear up for school reports, and we'd grab stacks at random, looking for polar bears, mountains. If by some miracle anyone found whatever she was writing about, we'd all marvel for a moment, then go back to our hopeless searches. Scarcity made this information—that feather—precious.

Just the other day, I clicked on a profile of a couple of artists who collaborated and married. Then I remembered I'd seen their first installation about 20 years ago at a gallery in Chelsea, with someone I adored who was indifferent to my adoration. The installation had drawn a feeling out of me; my understanding of art had been changed by it, though now I had only a dim memory of recorded voices, bubbling water. I'd long forgotten what the piece was called, but when I read the title—Dark Pool—I instantly remembered how the piece looked and sounded.

Without that surprise discovery, I wouldn't have enjoyed the sudden, vivid feeling of being 23 in New York, with nothing better to do than spend an afternoon in a gallery with a man I no longer know. I'm grateful for those 20 years of not entirely remembering.

Is the greatest pleasure in knowing, in not knowing, in partly knowing, or in opening a door in the mind and suddenly knowing everything years later? All I know is that while information may give us power, the deepest satisfaction lies in suspense.

When I was young and drew near the end of a beloved book, I'd save the last pages for days. I do the same thing now with the glut of online information. The other day I discovered a series of videos of Sergei Rachmaninoff, my favorite composer. But I watched just a fraction of the footage and left the rest for another time. Now I can enjoy the sweet anticipation of seeing it someday. Or not.

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah.com Spirit Newsletter!

These days, we can find out in mere moments what thresher sharks eat and whether ladybugs are nocturnal. We're exempt from waiting, denied the chance of surprise. And I'm convinced we are missing out on an essential human experience: not knowing.

It used to be that if I heard a bit of music I couldn't identify, I had to write it down, trying to score it on paper; I still have scraps from the '80s with hasty notations in the shorthand I invented. So many hours of my young life were spent hoping I'd learn the name of a song I'd heard on the radio. Singing fuzzily remembered lyrics for years. Having to be satisfied with that. The attendant heartache was part of the bargain—loving a piece of music didn't mean I got to know everything about it. I had to tolerate yearning. And I came to enjoy it: The answers to these little mysteries felt so beguilingly close, and it was tantalizing to sense them, just out of reach.

Once, in elementary school, we had an assembly about birds of prey. There was a great horned owl, and one of its feathers floated to the floor. After the presentation, I picked it up quickly, before anyone else could. I brought home the white fluff and made a paper envelope for it.

The feather was a prize—but it was also the only way I could keep that experience. There was no way to see that owl again, not really. I might find some small, unsatisfying image in an encyclopedia, but that would have been like looking at that magnificent creature through layers of fog, a photocopy of a photocopy.

My other option was to flip through stacks of National Geographic, hoping to stumble on a full-color photograph. My hometown library kept a room stocked with old issues that students could tear up for school reports, and we'd grab stacks at random, looking for polar bears, mountains. If by some miracle anyone found whatever she was writing about, we'd all marvel for a moment, then go back to our hopeless searches. Scarcity made this information—that feather—precious.

Just the other day, I clicked on a profile of a couple of artists who collaborated and married. Then I remembered I'd seen their first installation about 20 years ago at a gallery in Chelsea, with someone I adored who was indifferent to my adoration. The installation had drawn a feeling out of me; my understanding of art had been changed by it, though now I had only a dim memory of recorded voices, bubbling water. I'd long forgotten what the piece was called, but when I read the title—Dark Pool—I instantly remembered how the piece looked and sounded.

Without that surprise discovery, I wouldn't have enjoyed the sudden, vivid feeling of being 23 in New York, with nothing better to do than spend an afternoon in a gallery with a man I no longer know. I'm grateful for those 20 years of not entirely remembering.

Is the greatest pleasure in knowing, in not knowing, in partly knowing, or in opening a door in the mind and suddenly knowing everything years later? All I know is that while information may give us power, the deepest satisfaction lies in suspense.

When I was young and drew near the end of a beloved book, I'd save the last pages for days. I do the same thing now with the glut of online information. The other day I discovered a series of videos of Sergei Rachmaninoff, my favorite composer. But I watched just a fraction of the footage and left the rest for another time. Now I can enjoy the sweet anticipation of seeing it someday. Or not.

Want more stories like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the Oprah.com Spirit Newsletter!