The Man in the Picture: How I Came to Terms with My Father's Secret CIA Past

Her family secrets were too troubling to face, so she willfully kept herself in the dark. Now Leta McCollough Seletzky finally reckons with her father—and the truth.

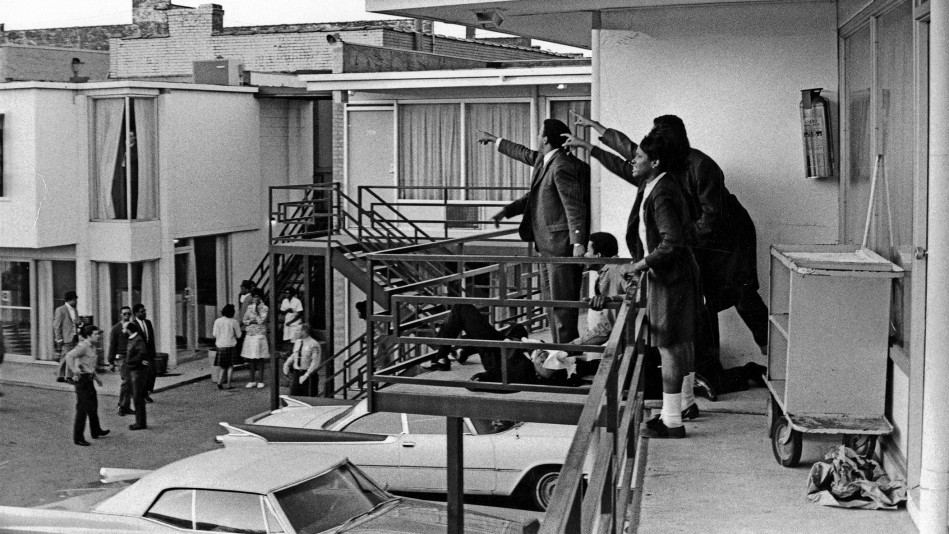

Photo: Joseph Louw/The Life Images Collection/Getty Images.

You've seen the photo: April 4, 1968, the exterior of Memphis's Lorraine Motel. A mortally wounded Martin Luther King Jr. lies on a second-floor balcony as blood pools around him on the gray concrete. The toes of his polished dress shoes stick out past the edge of the railing, over the cars in the lot below. Standing above him, three people frantically point to a rooming house across the street. A fourth person's gaze is fixed on the same spot, but with his right hand, he holds a white towel to King's shattered jaw. It's this man I found myself unable to look away from when I first saw the photo at the age of 4, maybe 5. He seems to be in shock, but alert, tensed, ready to leap to his feet. Please, God, let this not be happening, he might be thinking. Or maybe he's thinking nothing of the kind. The man's precise reasons for being on that balcony have long been touched by mystery—even to me. And I'm his daughter.

I have a flickering reel of early memories of my father, Marrell "Mac" McCollough: his bare ankles as I play on the floor while he watches football and drinks beer; a flash of straight, white teeth; him cooing his nickname for me, "Dee." Sparkling, sun-dappled late-'70s scenes. But there are darker ones, too: Mom and Dad shouting behind a closed bedroom door—about his drinking, his affairs. Her tearful calls to her mother on an avocado-green rotary phone: "I want to come home." My own helplessness and fear as our family's foundation crumbled beneath our feet.

They divorced in 1980 when I was 4 and my brother 2, Mom moving us from an anodyne northern Virginia townhouse to her soulful home city of Memphis. Later she told me that I cried for Dad after we left. Apparently, I once fixated on a man I spotted when we were out shopping, convinced he was my father by the sight of his legs and shoes. "Daddy!" I screamed over and over.

My brother and I were too young to understand the significance of his presence at King's assassination when Mom showed us that photo in the Commercial Appeal, our local newspaper. We knew only what she told us: "That's your dad; he was a policeman." Conversation over. Now he had a new job that took him to foreign countries for long stretches. Every few months, we'd get a fat envelope bearing strange stamps, stuffed with photos and a letter in his long, loopy script: How are you? I'm doing fine. Your mom told me you're in kindergarten now! I hope to see you soon. In some photos, he wore a green military uniform; in others, he stood next to a jeep. He was large framed and commanding; his brown skin glistened in the central African heat. He'd visit sporadically, swooping into town, always a surprise. In between these visits and missives, my brother and I had no idea where he was. Mom told us he worked "for the government." Her expression told us not to ask anything more.

Photo: Courtesy of Leta McCollough Seletzky

In Memphis, there was a host of welcoming faces: Grandma and Granddaddy, two elegant aunts, and four uncles who seemed almost as tall as the ceiling. We stayed in Grandma and Granddaddy's neat white bungalow. It had the air of a cabin in the country, long clotheslines swaying with billowing fabrics and tidy rows of vegetables bursting through the backyard's dark, turned earth. Mom got a job as a reporter at the Commercial Appeal, and Grandma and Granddaddy took care of us kids. "You heard from Mac?" Grandma would ask Mom from time to time. Mom would affirm tersely and look away. Conversation over.

Once or twice a year, Dad's brown Dodge van—"Big Choc," he called it—materialized next to the curb. Straight-backed and ebullient, he would stride up the walkway, an exotic visitor bearing curious gifts: a straw mask with cowrie shell eyes, a foot-tall Japanese geisha doll.

As I opened the door, he'd let out a full-throated laugh, saying, "Look at you, girl! Wow, you're getting tall!" He'd kiss my cheek, his stubble scratching my skin, then turn to my brother with a "My man!" before whisking us into Big Choc's shag-carpeted belly. We went on whirlwind jaunts across the city, tasting bony slabs of fried buffalo fish and riding the Zippin Pippin, Libertyland amusement park's wooden roller coaster.

When I was 11, Dad moved back to the U.S. and settled in northern Virginia, this time with a new bride and her aging poodle. My brother and I visited them for Thanksgiving in their spacious colonial-style home, where African carvings and tapestries filled the airy rooms.

Over that weekend, Dad took my brother and me to a boxy, featureless low-rise office building we'd never seen before; he flashed an ID badge and breezed through security. We crossed a vast, cubicle-filled room to get to Dad's office, where he closed the door, then asked if we knew what he did. "You work for the government," we said. "Actually, I work for the CIA," he told us matter-of-factly, looking us squarely in the eye. He didn't elaborate beyond directing us to keep that information to ourselves. True to our word, my brother and I didn't talk about it with anyone, even each other. But I knew the CIA was a spy agency that carried out missions doing who-knows-what across the world. Did the CIA watch us at home? I wondered. Did Dad have a gun? What did he actually do for them?

I became a bookish, surly teenager with a special interest in racial justice, having witnessed, among other things, the election of Memphis's first black mayor and the bigotry that his achievement coaxed from its hiding places. I pored over Alex Haley's The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth, a couple of books about the Black Panther Party. One day an older boy I'd sometimes talk to about social justice issues called himself a radical. I liked the sound of that. "I'm a radical," I announced to Mom in the car that afternoon. She shot me a look. "Don't you ever say that. You aren't any radical." My face burning, I vowed to keep quiet about my political views.

One afternoon in 1993, during my junior year of high school, I was lazily flipping through the Commercial Appeal when I came across an article about King's assassination. As I scanned the story, my father's name leaped out at me: The article said he'd worked undercover to infiltrate a black nationalist group called the Invaders. Undercover. Infiltrate. I scrambled to assemble the pieces in my head. Dad wasn't just any police officer at the Lorraine Motel when King was assassinated—he was a spy. The revelation felt like a body blow. I read the words over and over, struggling to take a full breath.

Instinctively, I sympathized with the Invaders. I'd read about the dirty tactics FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had employed to destroy the Black Panthers: spreading misinformation, harassing members and their families, possibly even murder. But I didn't ask my father to tell me his side of the story—not then, not in the 18 months before I left for college, not even when I interned at the CIA over two college summers—and lived with him and my stepmother.

I grew to like him during those summers, enjoying the lighthearted banter that deepened the dimple in his right cheek. "Remember how you used to love French fries when you were little?" he asked one evening in the kitchen. "You'd shout, 'More French fries!'" I didn't remember. I wished I did.

Illustration: John Ritter

But I hadn't forgotten what I'd read. And it still scared me. Especially after learning he'd been mentioned in a 1997 ABC Primetime Live segment that discussed conspiracy theories regarding King's assassination, and after hearing about a wrongful-death lawsuit brought by the Kings against several unnamed coconspirators, presumably including Dad. Alone at my computer, I'd occasionally leap down an online rabbit hole of innuendo and speculation, some advancing the idea that my father might have played a role in plotting the assassination. I just couldn't deal with that thought, so I packed it away deep in my subconscious. I was good at that.

By the summer of 2010, I was 34 years old, a married lawyer living in Houston. I'd just had a second child, and his birth had set something aflame: What would I tell the kids about their Grandaddy Mac? I could no longer ignore the cold draft that blew through my polite exchanges with Dad. So I picked up the phone.

I tried not to plan what I would say. Instead, after some chitchat, I simply pushed the words out. "I've been thinking about how we've never discussed Dr. King's assassination," I said. "I really want to hear about your experience."

Several beats of silence.

"Okay," he finally said.

"And not just the assassination," I stammered. "There's a lot I don't know about your life: your childhood, your time in the army, the CIA stuff...."

"That's a lot," he said, chuckling. "Let me get my thoughts together, and I'll send you some notes. Then we can talk."

He sounded relieved—even happy—that I'd asked.

About a week later, he emailed me a 17-page document. I inhaled sharply as I opened the letter, which began with a formal preamble in boldface: "Will be as forthcoming as possible, but will not disclose classified information. Will keep my solemn oath to my friends and country."

He launched into an account of his early childhood on a farm in 1940s Mississippi, describing his father ("Friends called him Nap, vanilla brown, cross-eyed—hit in eye with rock as child") and mother ("Prideful, primped in potato field"). He felt protected until his first taste of white supremacy, as a toddler: "At cotton gin, white man gave me a cherry soda. He'd been drinking from the bottle. I told him no, but Dad made me take it. Why? Didn't understand." That half-drunk soda was a show of dehumanizing superiority—as if my father were an animal happy to take a stranger's leavings.

Three pages in, I was heaving with tears. Imagining other gut-wrenching anecdotes that awaited me, I put the notes aside. For five years. I know, I know, but remember: I'd grown up under a family directive of don't ask, don't tell. I'd suppressed my curiosity about Dad's story for so long that five years seemed like nothing. I talked to him now and then, and knew he must have been wondering what I made of his story, but I never brought it up.

Then late one cold spring evening, with my husband working overseas and my kids tucked into bed, I was lonely and bored. Old aches and pains were roiling my spirit. I felt Dad's stories calling to me. In the darkness and silence, I started reading again.

The notes cleared up the timeline: In February 1968—a mere two months after he graduated from the police academy—Memphis's unprecedented sanitation strike began. The police department, concerned that the "radical" Invaders might orchestrate acts of mayhem, asked my father to embed with the group. They were staying at the Lorraine while assisting with King's upcoming march, and Dad duly reported their activities to the Memphis PD's intelligence division, which passed them along to the FBI. "My role was to collect information and to detect any plans for life-threatening criminal activity," Dad wrote. Two months later, King was dead.

Dad was a mole until 1969, when a community activist blew his cover. The discovery forced him to leave town temporarily, for his safety; activists had long been aware of snitches in their midst and viewed them with the utmost contempt. When he returned, he resumed his regular job in the department's intelligence division.

But how could he spy on the Invaders? Wasn't it treason to undermine people fighting for black rights? I steeled myself and asked him as much.

"That was a huge conflict for me," Dad admitted, his voice growing wobbly. "But enforcing the law equally, that's where I was coming from. By letting the department know the Invaders weren't a threat, we didn't have to go in shooting like Chicago did during the Black Panthers raid." Two activists died in that incident, in a hail of police bullets. What he was saying almost made sense.

When Dad and I started talking about the assassination, his tone turned sorrowful. He didn't cry that day, he said—numbed by shock, he locked into his professional duties. But a week earlier, when National Guard troops flooded the streets following King's first, chaotic Memphis march, he'd been overcome. "I felt like those tanks were there to occupy the African American community," he said. "It didn't matter that I was a police officer. They would have turned that .50-caliber machine gun on me. In my experience, soldiers, police officers, and CIA officers perform out of a sense of duty rather than how they feel about an assignment. How did I feel? I felt oppressed."

Photo: Courtesy of Leta McCollough Seletzky

Finally, I asked him what I'd spent decades wondering: "Do you think James Earl Ray acted alone? Or do you think the government saw Dr. King as a threat to national security and targeted him?" After all, an FBI memo had called King the "most dangerous Negro" in the nation.

Dad sighed. "I always believed that the U.S. government wouldn't assassinate its own citizens," he said. "I still believe that."

I understood. I get wanting to trust. Even when a cacophony of voices tells you maybe you shouldn't. Because sometimes stronger forces prevail.

Though we live 2,400 miles apart, my father and I have a relationship now. We talk and email nearly every day, and visit once or twice a year. We've bonded over our love of travel and weird food; we dream about visiting Ghana together, where he knows a restaurant that serves grasscutter, a giant rodent. He scolds me when I fail to send enough photos of my kids; I roll my eyes when he tells me how to shovel snow off my deck.

I feel close to him in a way I'd never thought possible. As much as I love it, I need it even more. So when doubt creeps in and I rehash the conspiracy theories, the secrets he might be protecting to keep the "solemn oaths" he swore as a cop and CIA agent, this thought shuts down all others: I've heard my father's side. He isn't just the man in the photograph anymore. I know him. And I choose to believe.