Soulful Reads: The Book Excerpt You Need to Read Today

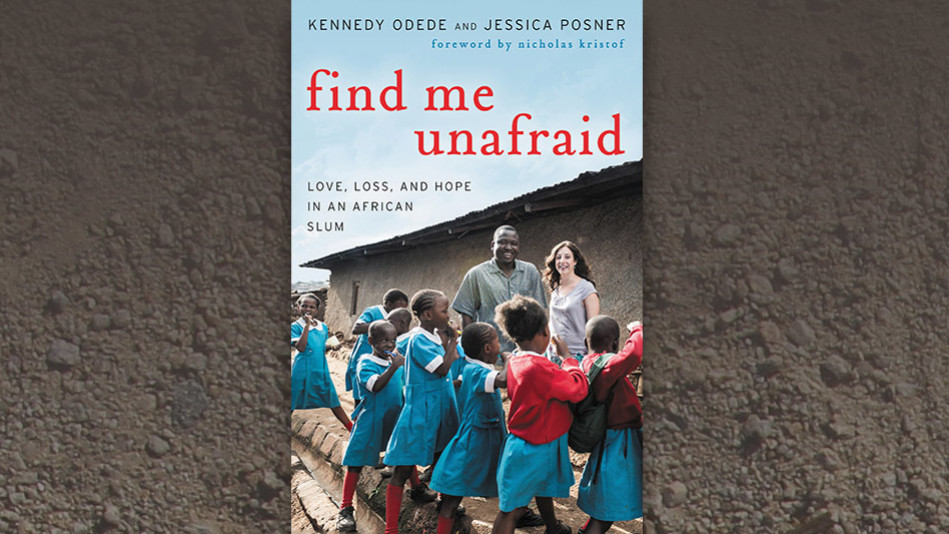

The inspiring book, Find Me Unafraid, tells the story of two young lovers—one raised with privilege in America, the other in poverty-stricken Africa. How they saved a generation of children begins with this moment...

The wall of discarded milk cartons is the only barrier between me and the gunfire outside. On a normal night, the noises of Kibera drift easily through these walls: reggae music, women selling vegetables by candlelight, drunken men shouting insults, dogs barking, a couple making love in their nearby shack. But now, Kibera is frozen. The entire slum is holding its breath, praying for this rain of bullets to pass, like any other storm.

I'm shivering under the bed. It's so dark and breathing is difficult. I can feel spiders crawling over my back and rats poking my toes, but I stay still, afraid that any movement will draw the uniformed men. I hear a high-pitched scream, like that of a young girl. The uniformed men are spraying bullets, and they hit anyone or anything unlucky enough to cross their path. I close my eyes and pray that the girl will survive. They didn't come to Kibera for her. They came for me.

I haven't eaten since yesterday, when the raids began; I'm starving for both water and food. In my pocket I have two dollars, which could ordinarily sustain me for at least a week. But even if I came out of hiding, there would be nowhere to get food. All the shops in the neighborhood have been closed or looted. The road going into Kibera has been shut down by the mobs and men in uniforms—paramilitary police. Nothing and nobody comes in and out without a struggle. They are sealing us in to die.

I hear gunfire, round after round in quick succession. The quiet afterward is almost as startling as the noise. I jump, and my head hits the underside of the bed hanging so low and close to the ground. My dog, Cheetah, barks outside the door. Please be quiet, I pray. Don't call them here. I lie frozen, anticipating the footsteps, but there is only blissful silence. Thirty minutes pass, and I do not hear any shots. Slowly, I drag my body out from underneath the bed. My legs are stiff, and I dance back and forth to rid myself of the pins and needles. I gingerly open my front door, pat Cheetah on his head and say firmly, quietly, "Stay." He isn't trained, just another nearly feral street dog, but I know he senses my urgency.

I knock on the rusting sheet-metal door of my neighbor, Mama Akinyi. No one answers."Please, Mama Akinyi, it's me, Ken," I whisper. Slowly, she comes to open the door and hastily sneaks me in. Her young face is gaunt. She is holding her little five-year-old girl, Akinyi. The same terror I feel is visible on Akinyi's face. I'm hungry and weak, and by good luck, Mama Akinyi notices my dry lips. She offers me some of the porridge that she has saved for her daughter. I ask for only a sip, just enough.

We tune the radio to a local station, keeping the volume hushed. She has not seen her husband for the last two days. Many people have been shot in Kibera.

"The bullets are close," I say.

Mama Akinyi looks at me through a veil of tears. Her husband might be among the dead. While we listen to the radio, we hear some men murmuring outside—with tin and cardboard f 5 walls, sounds easily trickle in and out. I perk my ears and hear from the murmurs that it's not just 20 or 30 people dead, but more than they can count. I don't need to listen any further. I thank Mama Akinyi and quickly go back to my house before endangering her family.

Several hours later, there is still quiet, which now seems more eerie than the noise. Then someone is knocking, quietly but urgently, at the door.

"Ken, Ken, are you there? Wake up! It's me, Chris."

Chris is just a few years younger than I am; I have known him his whole life. I open the door and see that he's frantic with terror. He is out of breath, panting, and I know what he will say before the words come out of his mouth.

"Leave, Ken, please. One of the men—he is showing people your picture, asking if they've seen you, if they know where you live."

I tell him to leave now, and he nods, knowing that any min- ute they might make their way here, using their guns and their money to get the information they need. I look at how skinny Chris is, and I thank him, from the bottom of my heart, for not selling me out. Even with this place turned to total chaos, I am reminded of how good people can be.

Cheetah begins to bark and won't stop. Then I hear the foot- steps. Heavy footsteps. The men still have to make their way around the treacherously narrow corner. I calculate that I have less than a minute to escape.

All I want to do is write her a letter, tell her how much I love her and tell her that I should have listened, I should have left. Tell her how sorry I am for all the things we will never get to do and see together.

But maybe it's just as well. Probably none of it would have come true, our late-night plans to build a life together probably just an adolescent romance. She so sweetly believes anything is possible and my heart would break watching her come to know what I know—that no matter how you try or believe, everything can end at the cry of a bullet, the sound of soldier's footsteps, the breaking of a heart. Eventually she'd tire of the challenges of living in my world, and I'd grow tired, too, living in hers.

I have my own dreams here, in Kibera.

Gunshot! Followed by a howl. Cheetah! They must have shot him in the alleyway, but I cannot risk going to look. Shaken from my thoughts, I run from the house. My heart beating, feet mov- ing, I take precious extra seconds to lock the padlock on my door. I run blindly, looking for any cranny where I can hide. There is a sheet of metal that covers the opening of a small alley near my door. I crawl behind it and will myself not to breathe, praying my shaking body won't bump the metal sheet and give away my hiding spot. Through a crack, I can see my door. The men materialize, weapons slung over their shoulders, dressed in fatigues, threatening in their uniformity.

Upon reaching my house, the men find the door is locked by my small padlock. Thank God I took the extra time to do that— with my door locked, it looks like I am not home. Kicking the door hard, their warning clear, the intruders storm off. I wait in my hiding spot for countless hours to make sure the scene wasn't staged, then I emerge panting and shaking, racked by both fear and relief.

I crawl on my stomach to the fence behind my house, climb over and fall hard on the other side. My torso hits the ground like a sack of maize, but I feel no pain, as if my body has reached its saturation point. I begin running, hiding in the secret shadows of the shanties. I have no destination in mind, only the desperate desire to get away, to reach some elusive safety. I have to step over bodies still lying where they fell—the mortuary sweep has not yet begun, and everyone's afraid to venture out to claim the fallen. Kibera is a city of the dead. I am not scared of the dead, but of the living.

This excerpt was taken from Find Me Unafraid: Love, Loss, and Hope in an African Slum by Kennedy Odede and Jessica Posner. The book tells the love story of Kennedy Odede, who grew up in poverty in Kenya, and Jessica Posner, who grew up in suburban Denver. The two joined forces to found Shining Hope for Communities, which brings education, healthcare, gender equality—and, most of all, dignity—to the people of Kibera, believed to be the largest slum in Africa.

I'm shivering under the bed. It's so dark and breathing is difficult. I can feel spiders crawling over my back and rats poking my toes, but I stay still, afraid that any movement will draw the uniformed men. I hear a high-pitched scream, like that of a young girl. The uniformed men are spraying bullets, and they hit anyone or anything unlucky enough to cross their path. I close my eyes and pray that the girl will survive. They didn't come to Kibera for her. They came for me.

I haven't eaten since yesterday, when the raids began; I'm starving for both water and food. In my pocket I have two dollars, which could ordinarily sustain me for at least a week. But even if I came out of hiding, there would be nowhere to get food. All the shops in the neighborhood have been closed or looted. The road going into Kibera has been shut down by the mobs and men in uniforms—paramilitary police. Nothing and nobody comes in and out without a struggle. They are sealing us in to die.

I hear gunfire, round after round in quick succession. The quiet afterward is almost as startling as the noise. I jump, and my head hits the underside of the bed hanging so low and close to the ground. My dog, Cheetah, barks outside the door. Please be quiet, I pray. Don't call them here. I lie frozen, anticipating the footsteps, but there is only blissful silence. Thirty minutes pass, and I do not hear any shots. Slowly, I drag my body out from underneath the bed. My legs are stiff, and I dance back and forth to rid myself of the pins and needles. I gingerly open my front door, pat Cheetah on his head and say firmly, quietly, "Stay." He isn't trained, just another nearly feral street dog, but I know he senses my urgency.

I knock on the rusting sheet-metal door of my neighbor, Mama Akinyi. No one answers."Please, Mama Akinyi, it's me, Ken," I whisper. Slowly, she comes to open the door and hastily sneaks me in. Her young face is gaunt. She is holding her little five-year-old girl, Akinyi. The same terror I feel is visible on Akinyi's face. I'm hungry and weak, and by good luck, Mama Akinyi notices my dry lips. She offers me some of the porridge that she has saved for her daughter. I ask for only a sip, just enough.

We tune the radio to a local station, keeping the volume hushed. She has not seen her husband for the last two days. Many people have been shot in Kibera.

"The bullets are close," I say.

Mama Akinyi looks at me through a veil of tears. Her husband might be among the dead. While we listen to the radio, we hear some men murmuring outside—with tin and cardboard f 5 walls, sounds easily trickle in and out. I perk my ears and hear from the murmurs that it's not just 20 or 30 people dead, but more than they can count. I don't need to listen any further. I thank Mama Akinyi and quickly go back to my house before endangering her family.

Several hours later, there is still quiet, which now seems more eerie than the noise. Then someone is knocking, quietly but urgently, at the door.

"Ken, Ken, are you there? Wake up! It's me, Chris."

Chris is just a few years younger than I am; I have known him his whole life. I open the door and see that he's frantic with terror. He is out of breath, panting, and I know what he will say before the words come out of his mouth.

"Leave, Ken, please. One of the men—he is showing people your picture, asking if they've seen you, if they know where you live."

I tell him to leave now, and he nods, knowing that any min- ute they might make their way here, using their guns and their money to get the information they need. I look at how skinny Chris is, and I thank him, from the bottom of my heart, for not selling me out. Even with this place turned to total chaos, I am reminded of how good people can be.

Cheetah begins to bark and won't stop. Then I hear the foot- steps. Heavy footsteps. The men still have to make their way around the treacherously narrow corner. I calculate that I have less than a minute to escape.

All I want to do is write her a letter, tell her how much I love her and tell her that I should have listened, I should have left. Tell her how sorry I am for all the things we will never get to do and see together.

But maybe it's just as well. Probably none of it would have come true, our late-night plans to build a life together probably just an adolescent romance. She so sweetly believes anything is possible and my heart would break watching her come to know what I know—that no matter how you try or believe, everything can end at the cry of a bullet, the sound of soldier's footsteps, the breaking of a heart. Eventually she'd tire of the challenges of living in my world, and I'd grow tired, too, living in hers.

I have my own dreams here, in Kibera.

Gunshot! Followed by a howl. Cheetah! They must have shot him in the alleyway, but I cannot risk going to look. Shaken from my thoughts, I run from the house. My heart beating, feet mov- ing, I take precious extra seconds to lock the padlock on my door. I run blindly, looking for any cranny where I can hide. There is a sheet of metal that covers the opening of a small alley near my door. I crawl behind it and will myself not to breathe, praying my shaking body won't bump the metal sheet and give away my hiding spot. Through a crack, I can see my door. The men materialize, weapons slung over their shoulders, dressed in fatigues, threatening in their uniformity.

Upon reaching my house, the men find the door is locked by my small padlock. Thank God I took the extra time to do that— with my door locked, it looks like I am not home. Kicking the door hard, their warning clear, the intruders storm off. I wait in my hiding spot for countless hours to make sure the scene wasn't staged, then I emerge panting and shaking, racked by both fear and relief.

I crawl on my stomach to the fence behind my house, climb over and fall hard on the other side. My torso hits the ground like a sack of maize, but I feel no pain, as if my body has reached its saturation point. I begin running, hiding in the secret shadows of the shanties. I have no destination in mind, only the desperate desire to get away, to reach some elusive safety. I have to step over bodies still lying where they fell—the mortuary sweep has not yet begun, and everyone's afraid to venture out to claim the fallen. Kibera is a city of the dead. I am not scared of the dead, but of the living.

This excerpt was taken from Find Me Unafraid: Love, Loss, and Hope in an African Slum by Kennedy Odede and Jessica Posner. The book tells the love story of Kennedy Odede, who grew up in poverty in Kenya, and Jessica Posner, who grew up in suburban Denver. The two joined forces to found Shining Hope for Communities, which brings education, healthcare, gender equality—and, most of all, dignity—to the people of Kibera, believed to be the largest slum in Africa.