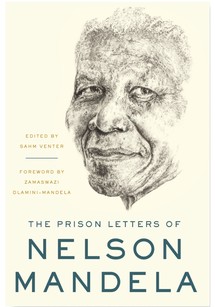

The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

By Nelson Mandela

640 pages;

Liveright

"I feel on top of the world...and am looking forward to the day when I will again see you enjoy once more the happy moments we have spent together in the past." Thus ends a note handwritten in 1967 by Nelson Mandela to my father. It appears in The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela, edited by Sahm Venter (Liveright)—a collection of 255 letters composed during Mandela's 10,052 days of incarceration and published in what would have been his 100th year. My father, Cecil Eprile, was the white editor of Johannesburg's Golden City Post, a newspaper staffed by and serving black South Africans, and in their shared mission to abolish apartheid, he and the great man had become friends.

Back then, being close to Mandela—nicknamed, at the time, the Black Pimpernel—was to risk arrest; doing what my father did in a racist police state was a tightrope act that required us all to be on our guard. My dad often broke the law just by doing his job—to entertain a black employee in our house was a crime. He was really rolling the dice when Mandela, the most wanted man in the country, showed up at our home for dinner disguised as a chauffeur. Danger lurked quite literally everywhere in those days, and my father often got impatient with my brother and me when we let anything slip about our lives to strangers, teachers, or even neighbors, some of whom he suspected of reporting on us. "Oh, my dad is down at the pool reading the Sunday papers," I once told one of his colleagues on the phone. When I related what I'd said, Dad was furious. "Never tell anyone where I am or what I'm doing," he yelled. For years I've worked to understand how heavily all the clandestine activity weighed on my father; Mandela's letter sheds new light on the man he was.

While Mandela's ascension to the presidency of South Africa now appears inevitable, back then it seemed far more likely that he'd die behind bars. His letters attest to the qualities that helped him triumph. Love, particularly for his second wife, Winnie, played a major part. He wrote to her: "your letters...form a solid wall between me and senility...& I am never certain whether I'm aging or rejuvenating." They also show him to be a caring father, who, like my own, mixed concern with sternness; he reached out to Dad to ask for help with a son who'd been expelled from school for taking part in a protest ("He may also be feeling lonely and unhappy...it may be better to call him to your office and discuss the matter"). He lamented that from prison, he was unable to support his family: "During the last 4 years I parasited on Winnie," he wrote. But what shines through, even in the darkest times, is Mandela's lively spirit, as when he joked with the wife of a fellow prisoner that wearing purdah during her visits denied him a glimpse of her beauty.

My father's death, 25 years ago, of a heart attack, denied me the chance to know more about the valiant work he did in South Africa and where he got the courage to do it. In reading these letters, I'm reminded that his ferociousness was about protecting us and fighting the best of all fights, in comradeship with one of the greatest warriors of all time.

— Tony Eprile