What "The Little House on the Prairie" Taught My Family About Living Simply

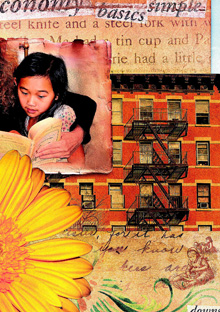

Illustration: David Vogin;

Photo courtesy of Marie Howe

Photo courtesy of Marie Howe

Inspired by the trials and triumphs of a resilient pioneer family, Marie Howe and her daughter find the joyful rhythm in a pared-down life.

Last summer my 8-year-old daughter and I returned to New York City after I didn't get the very lucrative job I'd hoped for in another city. Let's go home, honey, I said, and downsize into simplicity. And so we came back to our tiny fifth-floor walk-up apartment in the West Village, gave away or stored a lot of our stuff, and resettled into a space the size of a very small houseboat. Within two months the economy began to wobble and then falter. It seemed a good time to read the series I'd known as the Little House on the Prairie books, written by Laura Ingalls Wilder. I'd never read them as a child, had only glimpsed the TV series, and autumn was upon us. We sat on the couch under the lamplight, the book in my lap, my daughter leaning against me, warm and fresh from a shower. Through our two front windows: the worn red bricks of the 19th-century buildings across the street, and beyond them, the gleaming Empire State Building shining over the darkened city.

From our white couch each night we accompanied Ma and Pa as they moved their children, Laura, Mary, and Carrie, from a log cabin at the edge of the Big Woods in Wisconsin on to Kansas, into Indian territory, and still farther on to Plum Creek, where they spent that winter in a dugout sod house in a hill. With every move Pa built another cabin, another set of beds, fashioned the stable, and set his traps or plowed his field. And Ma unpacked their few clothes, set up the stove and the kitchen, settled the girls, and finally unpacked her single luxury, a china shepherdess statue, and set her on a high shelf—and the family began again.

By December I'd lost half my retirement savings, as had many of my friends, but I still had the job I'd returned to and was growing ever more grateful for it. The Ingalls family had moved three times, lost their good dog Jack, and suffered through a long bout of scarlet fever that had left Mary blind. Heat, hunger, grasshoppers. Pa worked the field, hunted when he could; Ma made supper, and the girls did their daily chores: fetching water, making the beds, setting and clearing the table, washing dishes. Page after page, they worked, then settled down to stitch quilt squares and study. If the chores had the feel of a regular metronome, the rhythm of their daily life seemed like a quiet song.

It was several weeks of reading before I noticed how the uncomplaining dignity of those people was slowly entering us. My daughter and I, almost unconsciously, began to slow down when we were at home. She began to read her schoolbooks out loud to me as I cooked dinner. (I cooked dinner! We are New Yorkers, used to eating out or ordering in.) And we started to refer to our housework as chores. Okay, honey, I'd say in the morning, before you leave for school we need to do the chores. And without a word of the usual resistance, she'd wash out the breakfast dishes as I straightened our three small rooms. At night, I, who'd always hated housework, experienced a deep satisfaction putting every single dish away—as Ma did. Sometimes I'd stand in the hall looking in—as if the tiny kitchen were the world, ordered, clean, and, in the little table-lamp light, lovely.