Our Own Bloomsbury

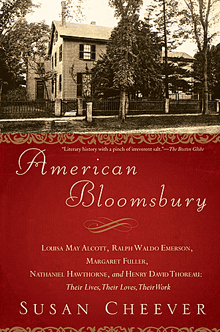

Susan Cheever's famous father, John, warned her not to "reduce literature to gossip," and now she suspects he is "spinning in his grave." Her investigative, speculative, suggestive biography, American Bloomsbury (Simon & Schuster), examines Concord, Massachusetts, in the middle of the 19th century, and the melodrama that played itself out among the transcendentalist writers and thinkers who lived there. With the fortune he inherited from his first wife, Ralph Waldo Emerson was able to create and support a community where Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Margaret Fuller, and a host of minor literary figures convened to flirt and argue, to fall in and out of love with ideas and each other, to break one another's hearts and change the way a nation imagined itself. Was Laurie in Little Women based on the strange, slight man named Henry David who taught Louisa May how to walk in the woods? Was the creation of Hester Prynne proof that in spite of his enduring marriage to the opium-addicted Sophia, Nathaniel Hawthorne never got over his riverside walks with the feisty Margaret Fuller, who had also captured Sophia's heart? Was the ode to the gentle Queequeg that comprises the first third of Moby-Dick Melville's attempt to exorcise his passionate feelings for Hawthorne? And in the midst of so much sexual tension, were most of these "lovers," as Cheever calls them, actually having sex? Or do we owe the greatest works of American literature—as we owe so many things—to the motivating forces of frustrated libido?

Susan Cheever's famous father, John, warned her not to "reduce literature to gossip," and now she suspects he is "spinning in his grave." Her investigative, speculative, suggestive biography, American Bloomsbury (Simon & Schuster), examines Concord, Massachusetts, in the middle of the 19th century, and the melodrama that played itself out among the transcendentalist writers and thinkers who lived there. With the fortune he inherited from his first wife, Ralph Waldo Emerson was able to create and support a community where Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Margaret Fuller, and a host of minor literary figures convened to flirt and argue, to fall in and out of love with ideas and each other, to break one another's hearts and change the way a nation imagined itself. Was Laurie in Little Women based on the strange, slight man named Henry David who taught Louisa May how to walk in the woods? Was the creation of Hester Prynne proof that in spite of his enduring marriage to the opium-addicted Sophia, Nathaniel Hawthorne never got over his riverside walks with the feisty Margaret Fuller, who had also captured Sophia's heart? Was the ode to the gentle Queequeg that comprises the first third of Moby-Dick Melville's attempt to exorcise his passionate feelings for Hawthorne? And in the midst of so much sexual tension, were most of these "lovers," as Cheever calls them, actually having sex? Or do we owe the greatest works of American literature—as we owe so many things—to the motivating forces of frustrated libido?