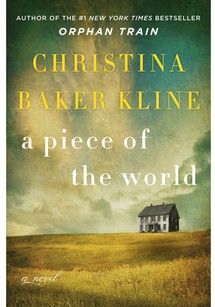

When Christina Baker Kline was a child, her father built an A-frame house on a Maine island just 75 feet wide to teach her self-reliance. Weekends and summers, the family pumped water, read by candlelight, used an outhouse, and stayed warm with only a stone fireplace. Not surprisingly, Kline grew interested in how the inner life could survive a lack of external comforts, an idea that sits at the heart of her 2013 book, Orphan Train. In her sixth novel, A Piece of the World, she revisits that dichotomy, applying her observations to the saga behind Andrew Wyeth's iconic painting, Christina's World.

The subject, Anna Christina Olson, a woman we once would have referred to as a spinster, lived with her brother on an austere Maine farm. A degenerative muscle condition gradually robbed her of mobility, though not of her zest for life. Although Wyeth substituted the torso of his young wife for that of the middle-aged Christina, the rest of the image is accurate: Christina's determination to get around on her own meant that she preferred to drag herself in a crawl across her land instead of resorting to crutches or a wheelchair. Yet A Piece of the World is more than a paean to the human spirit; it's the decoding of a mystery. Who has not gazed on Wyeth's picture and wondered, Why does that girl have so very far to go? Woven throughout this tale of childhood agony and solitary adulthood are wraiths from Christina's ancestry—among them the doomed witches of Salem and that other New England recluse, Emily Dickinson. Kline's gift is to dispense with the fustiness and fact-clogged drama of some historical novels to tell a pure, powerful story of suffering met with a fight.

Don't look here for arcane misdeeds or hidden love affairs, or for a big feel-good ending. Unable to break free from the prison of her body, Christina may simply have chosen to live an examined life—much like the character Kline creates, filling in the biographical record with her own contrivances. Kline writes of her heroine, "There she is, that girl, on a planet of grass. Her wants are simple: to tilt her face to the sun and feel its warmth. To clutch the earth beneath her fingers. To escape from and return to the house she was born in. To see her life from a distance, as clear as a photograph, as mysterious as a fairy tale."