Photo: Rob Howard

Our nation's first Latina Supreme Court justice knows a thing or two about triumphing over adversity. As she prepares to publish a memoir, My Beloved World, Sonia Sotomayor chats candidly with Oprah about her humble beginnings in the Bronx, her life-changing call from President Obama, and the perils of dating when you sit on the highest court in the land.

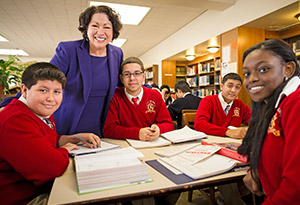

The first thing that strikes me about Justice Sonia Sotomayor is her warmth. The second—her shoes. I've never pictured a member of our nation's highest court wearing leopard-print pumps, but that's what she has on when I meet her outside her old high school, Cardinal Spellman, in the Bronx (she graduated in 1972). As we walk the halls together, I learn that I have more in common with this Supreme Court justice than I would have thought possible. Besides being practically the same age, we've both loved books since childhood. Like me, she had a thing for the Encyclopedia Britannica, and like me, she now reads most everything on her iPad. We both joined the forensics team in high school, where we learned "how to speak and be persuasive," as she puts it. We both value our friendships: I've got Gayle along with me today, while the justice has brought Miriam Gonzerelli, her cousin and lifelong close friend, whom I read all about in the justice's new book, My Beloved World (she writes that Miriam was always the stylish one, while she herself dressed badly because "I'm competitive enough that I'll eventually withdraw from any consistently losing battle." It took her years to realize that being a smart lawyer didn't preclude her from also enjoying her "feminine side").

As the justice shares her memories of bounding up and down the stairs of Cardinal Spellman "a million times a day," I learn that there's one thing she and I don't share: I was never sent to the principal's office, while the justice evidently spent a lot of time there. She writes in My Beloved World that her family nickname was Ají, or "hot pepper." (And she has a sign in her office that reads "Well-Behaved Women Never Make History.") Certainly, as rambunctious as she was, the young Puerto Rican daughter of a nurse and a factory worker never imagined she'd someday return to find her face on a banner in her school's entryway.

I have no idea how a woman who spends her days weighing in on the greatest legal issues of our time managed to write a book, but I'm sure glad she did. My Beloved World is a moving homage to the justice's tight-knit family and their life in New York City in the '60s and '70s. I wanted to hear all about her amazing journey from the projects to Princeton to the height of the legal profession, which is why I've met her here in the Bronx, where it all started. "It was here at this school," she tells me, "that I began to see a larger world." And it's in the library, surrounded by many of the very same books she devoured as a teenager, that we begin.

Next: Read the full interview

OPRAH: More than anything, your book feels like a love letter to your life growing up in the Bronx.

SONIA SOTOMAYOR: Because that's what it is. So many people grew up with challenges, as I did. There weren't always happy things happening to me or around me. But when you look at the core of goodness within yourself—at the optimism and hope—you realize it comes from the environment you grew up in.

O: You say in the book that there was a depth of happiness there that fueled your optimism. Still, there were, as you say, challenges.

SS: Yes. An alcoholic father, poverty, my own juvenile diabetes, the limited English my parents spoke—although my mother has become completely bilingual since. All these things intrude on what most people think of as happiness.

O: It had never occurred to me that growing up in a household where everyone speaks Spanish could make you feel embarrassed.

SS: When everyone at school is speaking one language, and a lot of your classmates' parents also speak it, and you go home and see that your community is different—there is a sense of shame attached to that. It really takes growing up to treasure the specialness of being different. Now I understand that I've gotten to enjoy things that others have not, whether it's the laughter, the poetry of my Spanish language—I love Spanish poetry, because my grandmother loved it—our food, our music. Everything about my culture has given me enormous education and joy.

O: In the book, you describe Saturdays at your grandmother's house, when your titis, or aunts, would be in the kitchen, making—

SS: The sofrito. It's the base for all Puerto Rican cooking.

O: I actually underlined that, because I thought, "Would like to have some of that someday."

SS: Those Saturdays were so special to me. My aunts and my grandmother would have one blender going for eight hours, and they'd be chopping and cutting up vegetables of all kinds. Hearing them talking, laughing, gossiping—I was always the inquisitive one, trying to listen in on their conversations.

O: Literally, with your ear against the door! You also write about being at your grandmother's house as an 8-year-old, watching for the signs—which you could see even before your mother could—that your father was spiraling out of control. He'd get drunk and drunker, your mother would get angry, he'd leave, and then you'd all get home later and there would be an argument. How do you think you were affected by growing up with an alcoholic father?

SS: You become a watchful child. I listened very, very carefully to the world around me to pick up the signals of when trouble was coming. Not that I could stop it. But it made me observant. That was helpful when I became a lawyer, because I knew how to read people's signals. When a witness hesitated, my mind would race to the conclusion that he was trying to hide something. What was it? I'd dissect the story in my brain and nine times out of ten figure out a hole they were trying to avoid.

O: One of the most compelling stories you tell in My Beloved World is about discovering when you were not yet 8 that you had juvenile diabetes. You had to give yourself a shot every day. You still do?

SS: I give myself three to six shots a day now. Back then it was only one.

O: You paint the picture so vividly of when your father went to give you that first shot, and his hands were shaking. Was that because he was nervous, or drinking?

SS: I don't know if he was drinking in that moment. You couldn't really tell in the mornings. I think he had alcoholic neuropathy, the shaking that happens to some alcoholics. But I'm sure the nerves just compounded it that day. It's terrifying for a parent to have a child diagnosed with a chronic disease. The prognosis back then was very bad. I don't want to scare children with diabetes, so I underscore that it's not this way today, but when I was diagnosed you could expect to die in your 40s. If you were lucky, you'd make 50.

O: Did this knowledge affect how you lived your life?

SS: Absolutely. I never thought of taking a year off school or out of my career to go do something else. I was so anxious to live life to its fullest, to wring out of every minute as much as I could, that there was a sort of hunger in me. To do as much and learn as much as I could in the limited time I thought I had.

Next: What Sonia Sotomayor says about human nature

SONIA SOTOMAYOR: Because that's what it is. So many people grew up with challenges, as I did. There weren't always happy things happening to me or around me. But when you look at the core of goodness within yourself—at the optimism and hope—you realize it comes from the environment you grew up in.

O: You say in the book that there was a depth of happiness there that fueled your optimism. Still, there were, as you say, challenges.

SS: Yes. An alcoholic father, poverty, my own juvenile diabetes, the limited English my parents spoke—although my mother has become completely bilingual since. All these things intrude on what most people think of as happiness.

O: It had never occurred to me that growing up in a household where everyone speaks Spanish could make you feel embarrassed.

SS: When everyone at school is speaking one language, and a lot of your classmates' parents also speak it, and you go home and see that your community is different—there is a sense of shame attached to that. It really takes growing up to treasure the specialness of being different. Now I understand that I've gotten to enjoy things that others have not, whether it's the laughter, the poetry of my Spanish language—I love Spanish poetry, because my grandmother loved it—our food, our music. Everything about my culture has given me enormous education and joy.

O: In the book, you describe Saturdays at your grandmother's house, when your titis, or aunts, would be in the kitchen, making—

SS: The sofrito. It's the base for all Puerto Rican cooking.

O: I actually underlined that, because I thought, "Would like to have some of that someday."

SS: Those Saturdays were so special to me. My aunts and my grandmother would have one blender going for eight hours, and they'd be chopping and cutting up vegetables of all kinds. Hearing them talking, laughing, gossiping—I was always the inquisitive one, trying to listen in on their conversations.

O: Literally, with your ear against the door! You also write about being at your grandmother's house as an 8-year-old, watching for the signs—which you could see even before your mother could—that your father was spiraling out of control. He'd get drunk and drunker, your mother would get angry, he'd leave, and then you'd all get home later and there would be an argument. How do you think you were affected by growing up with an alcoholic father?

SS: You become a watchful child. I listened very, very carefully to the world around me to pick up the signals of when trouble was coming. Not that I could stop it. But it made me observant. That was helpful when I became a lawyer, because I knew how to read people's signals. When a witness hesitated, my mind would race to the conclusion that he was trying to hide something. What was it? I'd dissect the story in my brain and nine times out of ten figure out a hole they were trying to avoid.

O: One of the most compelling stories you tell in My Beloved World is about discovering when you were not yet 8 that you had juvenile diabetes. You had to give yourself a shot every day. You still do?

SS: I give myself three to six shots a day now. Back then it was only one.

O: You paint the picture so vividly of when your father went to give you that first shot, and his hands were shaking. Was that because he was nervous, or drinking?

SS: I don't know if he was drinking in that moment. You couldn't really tell in the mornings. I think he had alcoholic neuropathy, the shaking that happens to some alcoholics. But I'm sure the nerves just compounded it that day. It's terrifying for a parent to have a child diagnosed with a chronic disease. The prognosis back then was very bad. I don't want to scare children with diabetes, so I underscore that it's not this way today, but when I was diagnosed you could expect to die in your 40s. If you were lucky, you'd make 50.

O: Did this knowledge affect how you lived your life?

SS: Absolutely. I never thought of taking a year off school or out of my career to go do something else. I was so anxious to live life to its fullest, to wring out of every minute as much as I could, that there was a sort of hunger in me. To do as much and learn as much as I could in the limited time I thought I had.

Next: What Sonia Sotomayor says about human nature

Photo: Rob Howard

O: You pose a question in your book that I want to ask you: How is it that some people are faced with adversity and it makes them want to rise to the highest part of themselves, and other people, faced with the same adversity, get knocked down? Is that nature or nurture?

SS: I think it's a combination of the two. There are people who really don't respond to competition, who viscerally recoil from it. And then there are people for whom it sets their spirits on fire. I do think that the nurturing gives you the confidence to have optimism. And to try things even when there's a risk of failure. One of the conversations I often have with kids is, Look, you're going to experience failure; we all have. The test of your character is how often you get up and try again.

O: Your father died when you were almost 9 years old. Afterward, your mother went into a dreadful period of mourning, which you didn't understand because they'd argued all the time. You'd assumed in some ways that things would get easier after he died.

SS: I didn't grow up understanding that my mom and dad had actually loved each other. So I couldn't make sense of her grief. I thought they'd just married because my mother needed a place to live after she left the WACs [the Women's Army Corps, with which she'd left Puerto Rico in 1944]. It wasn't until I started writing this book—and it's been one of the great gifts of writing this book—that I found a father I never knew. I learned that he and my mother had actually had a romance. When I sat down with my mother and shared my own impressions, she'd say, "Sonia, that's wrong."

O: Because all you'd seen as a child was their unhappiness. She wouldn't even come home. She was working nights at a hospital....

SS: She did everything she could to escape. And that meant, I felt, abandoning us to my dad. I could forgive my father for his drinking, because I understood it was an addiction and outside his control. I found it harder to forgive my mother—I expected more from her.

O: You write that even when she was home, and you shared a bed with her, it was like lying next to a log. She'd turn her back to you at night, cold and distant.

SS: You know, writing about personal moments like that is very, very difficult. But what I wanted was to give anyone who reads the book who has ever felt completely alone in the world—I wanted to give them hope.

O: How long were you angry with her? When did you start to soften and forgive?

SS: Well, some of it started once I began to come out of myself. I'd been very, very withdrawn for most of my life. I think that comes from having an alcoholic father—no one was welcome in my house; no one wanted to be there. As a result, my brother, Junior [now a doctor near Syracuse], and I were alone a lot. I was probably in my 30s before I began to realize that I didn't like being alone all that much, and I wanted to have more warmth in my life. So I started asking all the kids I knew, relatives and godchildren—I said, "I'm missing something really important. Nobody hugs me. Would you agree to give me a hug when you see me?" Every single one readily agreed, and they still do.

O: You have no children, but you have five godchildren.

SS: Actually, now I have six! I just baptized one a week ago.

O: Congratulations! So you went out consciously seeking the love and affection that you did not have.

SS: And learning how to give it. That's when things really started to thaw between my mother and me. When my mom met Michelle Obama, she gave the First Lady a hug. That just goes to show how we've both warmed! Now I don't think there is a friend or anyone else in my life who doesn't know how much I adore my mother and how proud I am of her and how extraordinary she is. But we're both frail human beings. Everyone makes mistakes. None of us have the tools to manage every situation that's thrown at us.

Next: What her mother did right

SS: I think it's a combination of the two. There are people who really don't respond to competition, who viscerally recoil from it. And then there are people for whom it sets their spirits on fire. I do think that the nurturing gives you the confidence to have optimism. And to try things even when there's a risk of failure. One of the conversations I often have with kids is, Look, you're going to experience failure; we all have. The test of your character is how often you get up and try again.

O: Your father died when you were almost 9 years old. Afterward, your mother went into a dreadful period of mourning, which you didn't understand because they'd argued all the time. You'd assumed in some ways that things would get easier after he died.

SS: I didn't grow up understanding that my mom and dad had actually loved each other. So I couldn't make sense of her grief. I thought they'd just married because my mother needed a place to live after she left the WACs [the Women's Army Corps, with which she'd left Puerto Rico in 1944]. It wasn't until I started writing this book—and it's been one of the great gifts of writing this book—that I found a father I never knew. I learned that he and my mother had actually had a romance. When I sat down with my mother and shared my own impressions, she'd say, "Sonia, that's wrong."

O: Because all you'd seen as a child was their unhappiness. She wouldn't even come home. She was working nights at a hospital....

SS: She did everything she could to escape. And that meant, I felt, abandoning us to my dad. I could forgive my father for his drinking, because I understood it was an addiction and outside his control. I found it harder to forgive my mother—I expected more from her.

O: You write that even when she was home, and you shared a bed with her, it was like lying next to a log. She'd turn her back to you at night, cold and distant.

SS: You know, writing about personal moments like that is very, very difficult. But what I wanted was to give anyone who reads the book who has ever felt completely alone in the world—I wanted to give them hope.

O: How long were you angry with her? When did you start to soften and forgive?

SS: Well, some of it started once I began to come out of myself. I'd been very, very withdrawn for most of my life. I think that comes from having an alcoholic father—no one was welcome in my house; no one wanted to be there. As a result, my brother, Junior [now a doctor near Syracuse], and I were alone a lot. I was probably in my 30s before I began to realize that I didn't like being alone all that much, and I wanted to have more warmth in my life. So I started asking all the kids I knew, relatives and godchildren—I said, "I'm missing something really important. Nobody hugs me. Would you agree to give me a hug when you see me?" Every single one readily agreed, and they still do.

O: You have no children, but you have five godchildren.

SS: Actually, now I have six! I just baptized one a week ago.

O: Congratulations! So you went out consciously seeking the love and affection that you did not have.

SS: And learning how to give it. That's when things really started to thaw between my mother and me. When my mom met Michelle Obama, she gave the First Lady a hug. That just goes to show how we've both warmed! Now I don't think there is a friend or anyone else in my life who doesn't know how much I adore my mother and how proud I am of her and how extraordinary she is. But we're both frail human beings. Everyone makes mistakes. None of us have the tools to manage every situation that's thrown at us.

Next: What her mother did right

O: At the end of the day, despite her faults, your mother raised a Supreme Court justice and a doctor. How was she able to do that, basically as a single mother?

SS: She will tell you that she did it by not interfering. What she says is, "I never tried to steer you away from the things you wanted to do that were not bad for you. When you said, 'Mom, I want to go away to college,' I didn't know anything about that, but I knew it wasn't going to be a bad thing, so I supported you."

O: You also write that your mother valued education highly. When you were at Cardinal Spellman, she went back to school to become a registered nurse.

SS: She taught me my values, and my mother's values are incredible: education, honesty, discipline, and hard work.

O: When you were admitted to Princeton, there had not yet been a single Latina graduate. What was it like being a Latina on campus in the '70s?

SS: Well, there were maybe 15 Latinos in the whole school. We tended to gravitate to each other, if only because when you feel like you've arrived in an alien land—which is how I describe my first few years at Princeton—you seek out comfort from those who are similar to you. One of my messages in the book to minority students, even today, is that it's important to draw strength from your community. All of us need the comfort and security of that which is familiar. But then use it as a springboard to explore the world; don't isolate yourself in what you know.

O: That's really important.

SS: I have always been actively involved in my community, belonging to organizations that promote the interests of Latinos. But I also know that the issues we confront are the same issues, in many respects, as the larger community. So what we do helps not just us but everybody.

O: In the book, you write: "I didn't know I had a sense of limitation until I got into the greater world." What in that world made you feel your Puerto Rican-ness, your Latina-ness?

SS: When I was nominated to the Supreme Court, one of the many attacks I faced was that I wasn't smart enough. That statement has followed me in every step of my career. Is she good enough? Is she smart enough? At each stage there's been a sense, sometimes, that because you might have had a different life, that because you may have grown up poor, that defines you—and that you don't have the capacity or ability to achieve without a little extra help. That people have had to cut you a break so that you can be successful. I daresay that I'm looking at you, Oprah, and that you have experienced the same.

O: A little bit [laughs]. But you know what, I have actually loved it, because I've been underestimated every step of the way, and it's so exciting when you can prove them all wrong.

SS: Oh, it is wonderful. When I first became a judge on the district court, I had one lawyer who came to argue before me, and he was looking off to the side as he was talking. I started asking him questions, and all of a sudden he whipped around and looked at me intently. I could see in his eyes that he had finally figured out, "This is no dummy, I'd better pay attention." It is satisfying to see that.

O: What did you think when you heard President Obama was considering you for the Supreme Court?

SS: I thought he was crazy. No, seriously—I am not a betting woman, but I kept telling my friends, "He's never gonna pick me." Not in a million years. I'm very rational, and I'm another New Yorker—at the time there were a few others—and I'd had a very contentious nomination to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. I couldn't figure out why he'd elect to go into a battle over me. And so I was in total disbelief when I was called that day.

O: Was it something you'd aspired to, the Supreme Court, or ever thought about?

SS: The minute I began to understand the importance of the Supreme Court, which really wasn't until law school, I also understood how unlikely it was to become a justice. It's said that you have to be struck by lightning. So it's not something you can live your life aspiring to. In the deep, deep recesses of your fantasies, you think, "Wouldn't that be cool?" But really, it's just a fantasy.

O: So when he called you...

SS: I was at home. I'd had an interview with him earlier that day—it was the first time we'd met—and he told me that he'd call to tell me his decision.

O: That he would personally call you.

SS: Yes. His staff had sent me home to New York to pack, just in case he picked me. I was standing in my dining room, the phone rang, and the first thing I heard was, "This is the White House switchboard operator; please wait, the president's coming on the line."

O: Oooooooh!

Next: What President Obama said in that phone call

SS: She will tell you that she did it by not interfering. What she says is, "I never tried to steer you away from the things you wanted to do that were not bad for you. When you said, 'Mom, I want to go away to college,' I didn't know anything about that, but I knew it wasn't going to be a bad thing, so I supported you."

O: You also write that your mother valued education highly. When you were at Cardinal Spellman, she went back to school to become a registered nurse.

SS: She taught me my values, and my mother's values are incredible: education, honesty, discipline, and hard work.

O: When you were admitted to Princeton, there had not yet been a single Latina graduate. What was it like being a Latina on campus in the '70s?

SS: Well, there were maybe 15 Latinos in the whole school. We tended to gravitate to each other, if only because when you feel like you've arrived in an alien land—which is how I describe my first few years at Princeton—you seek out comfort from those who are similar to you. One of my messages in the book to minority students, even today, is that it's important to draw strength from your community. All of us need the comfort and security of that which is familiar. But then use it as a springboard to explore the world; don't isolate yourself in what you know.

O: That's really important.

SS: I have always been actively involved in my community, belonging to organizations that promote the interests of Latinos. But I also know that the issues we confront are the same issues, in many respects, as the larger community. So what we do helps not just us but everybody.

O: In the book, you write: "I didn't know I had a sense of limitation until I got into the greater world." What in that world made you feel your Puerto Rican-ness, your Latina-ness?

SS: When I was nominated to the Supreme Court, one of the many attacks I faced was that I wasn't smart enough. That statement has followed me in every step of my career. Is she good enough? Is she smart enough? At each stage there's been a sense, sometimes, that because you might have had a different life, that because you may have grown up poor, that defines you—and that you don't have the capacity or ability to achieve without a little extra help. That people have had to cut you a break so that you can be successful. I daresay that I'm looking at you, Oprah, and that you have experienced the same.

O: A little bit [laughs]. But you know what, I have actually loved it, because I've been underestimated every step of the way, and it's so exciting when you can prove them all wrong.

SS: Oh, it is wonderful. When I first became a judge on the district court, I had one lawyer who came to argue before me, and he was looking off to the side as he was talking. I started asking him questions, and all of a sudden he whipped around and looked at me intently. I could see in his eyes that he had finally figured out, "This is no dummy, I'd better pay attention." It is satisfying to see that.

O: What did you think when you heard President Obama was considering you for the Supreme Court?

SS: I thought he was crazy. No, seriously—I am not a betting woman, but I kept telling my friends, "He's never gonna pick me." Not in a million years. I'm very rational, and I'm another New Yorker—at the time there were a few others—and I'd had a very contentious nomination to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. I couldn't figure out why he'd elect to go into a battle over me. And so I was in total disbelief when I was called that day.

O: Was it something you'd aspired to, the Supreme Court, or ever thought about?

SS: The minute I began to understand the importance of the Supreme Court, which really wasn't until law school, I also understood how unlikely it was to become a justice. It's said that you have to be struck by lightning. So it's not something you can live your life aspiring to. In the deep, deep recesses of your fantasies, you think, "Wouldn't that be cool?" But really, it's just a fantasy.

O: So when he called you...

SS: I was at home. I'd had an interview with him earlier that day—it was the first time we'd met—and he told me that he'd call to tell me his decision.

O: That he would personally call you.

SS: Yes. His staff had sent me home to New York to pack, just in case he picked me. I was standing in my dining room, the phone rang, and the first thing I heard was, "This is the White House switchboard operator; please wait, the president's coming on the line."

O: Oooooooh!

Next: What President Obama said in that phone call

Photo: Rob Howard

SS: He got on the phone and said, "Judge, I have decided to make you my nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court." Now, I don't cry. But the tears just started to come down. My heart was beating so hard that I actually thought he could hear it. I realized I'd put my right hand to my heart to try to quiet it. It was the most electrifying moment of my life. The next day I was walking to the East Room at the White House, where the press statement of my nomination was about to happen, flanked by the president and vice president. They have longer legs than me, so I whispered, "Please wait." And they turned around and smiled and waited for me to catch up. In that moment, I had an out-of-body experience. I was so overcome with emotion; I knew that if I stayed within my body I couldn't deal with what I had to do. So it was like all of that energy came out of my body and started watching me from up here [motions to the sky].

O: You had to let some of it go, because it wouldn't have been good to start crying in that moment.

SS: And I lived like that for about a year and a half! [Laughs.]

O: Out of body.

SS: Well, everything was so extraordinary after that. It was almost like my emotions and my body weren't quite connected for a while. It took a long time to come back to Earth.

O: President Obama asked that you make him two promises. They were?

SS: To follow the advice of his team, which I think I did. And the second was to stay connected to my community. My response to him was, "Mr. President, that's an easy promise to make. I don't know how to do anything but."

O: Before your confirmation hearings, when you were suddenly thrust into the spotlight, one quote got you into a lot of hot water. You'd said in a previous speech, "I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn't lived that life." That was repeated and repeated and repeated. Did you regret saying it, or do you think your comment was misunderstood?

SS: My comment was clearly misunderstood. And it was taken out of context. Anyone who reads the whole speech understands that the audience I was talking to was young people, and that what I was trying to convey to them was that their life experiences had value.

O: That everything you describe in the pages of My Beloved World has value.

SS: Absolutely. In that speech, my rhetoric was imprecise. Because I didn't mean to suggest that others were less. What I was trying to communicate was that we are equal. We bring maybe a different kind of richness, but it's a richness, too.

O: As a Supreme Court justice, what is the role of empathy in your decisions—or do you approach each case trying to be emotionless?

SS: You can't be emotionless. No one can. I don't want to describe the details of some of the crimes we read about; they're barbaric. People in some situations act worse than animals. You can't be a judge if you try to be a robot. Because then you're not going to be able to look at both sides, and hear both sides. At the same time, if you're being ruled by emotion, then you're not being fair and impartial. So what do you do with your emotions? My feeling is that you have to be aware. You have to be aware that you might be angry with a defendant, and then acknowledge and deal with that anger as a person—and consciously set it aside.

O: Would you describe yourself as being tough on the bench?

SS: [Low voice.] Demanding.

O: You're demanding.

SS: Tough, yes, in the sense that I want lawyers to be prepared. I think that being a lawyer is one of the best jobs in the whole wide world.

O: Really?

SS: You want to know why? Because every lawyer, no matter whom they represent, is trying to help someone, whether it's a person, a corporation, a government entity, or a small or big business. To me, lawyering is the height of service—and being involved in this profession is a gift. Any lawyer who is unhappy should go back to square one and start again.

Next: How she copes with the pressure

O: You had to let some of it go, because it wouldn't have been good to start crying in that moment.

SS: And I lived like that for about a year and a half! [Laughs.]

O: Out of body.

SS: Well, everything was so extraordinary after that. It was almost like my emotions and my body weren't quite connected for a while. It took a long time to come back to Earth.

O: President Obama asked that you make him two promises. They were?

SS: To follow the advice of his team, which I think I did. And the second was to stay connected to my community. My response to him was, "Mr. President, that's an easy promise to make. I don't know how to do anything but."

O: Before your confirmation hearings, when you were suddenly thrust into the spotlight, one quote got you into a lot of hot water. You'd said in a previous speech, "I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn't lived that life." That was repeated and repeated and repeated. Did you regret saying it, or do you think your comment was misunderstood?

SS: My comment was clearly misunderstood. And it was taken out of context. Anyone who reads the whole speech understands that the audience I was talking to was young people, and that what I was trying to convey to them was that their life experiences had value.

O: That everything you describe in the pages of My Beloved World has value.

SS: Absolutely. In that speech, my rhetoric was imprecise. Because I didn't mean to suggest that others were less. What I was trying to communicate was that we are equal. We bring maybe a different kind of richness, but it's a richness, too.

O: As a Supreme Court justice, what is the role of empathy in your decisions—or do you approach each case trying to be emotionless?

SS: You can't be emotionless. No one can. I don't want to describe the details of some of the crimes we read about; they're barbaric. People in some situations act worse than animals. You can't be a judge if you try to be a robot. Because then you're not going to be able to look at both sides, and hear both sides. At the same time, if you're being ruled by emotion, then you're not being fair and impartial. So what do you do with your emotions? My feeling is that you have to be aware. You have to be aware that you might be angry with a defendant, and then acknowledge and deal with that anger as a person—and consciously set it aside.

O: Would you describe yourself as being tough on the bench?

SS: [Low voice.] Demanding.

O: You're demanding.

SS: Tough, yes, in the sense that I want lawyers to be prepared. I think that being a lawyer is one of the best jobs in the whole wide world.

O: Really?

SS: You want to know why? Because every lawyer, no matter whom they represent, is trying to help someone, whether it's a person, a corporation, a government entity, or a small or big business. To me, lawyering is the height of service—and being involved in this profession is a gift. Any lawyer who is unhappy should go back to square one and start again.

Next: How she copes with the pressure

O: Wow. Carlos Ortiz of the Hispanic National Bar Association—

SS: I love Carlos.

O: He said that you carry the hopes and aspirations of more than 50 million people. That's a lot of pressure. Do you feel that?

SS: Yes.

O: You do.

SS: I didn't think I would. Mostly because at first, I didn't think it was true. I didn't understand it until after I became a justice. Now when I talk to kids, I often tell them, "I'm going to disappoint you someday. I won't be worth my salt as a judge if I don't render at least one decision that makes you unhappy. Because if I'm following the law—and I don't write them—there has to be some decision you won't like. Please don't judge any person by one act. Take from them the good and don't concentrate on the little things that make you unhappy." That's my approach to family and friends, too.

O: You write in your book about your marriage, after you graduated Princeton, to your high school sweetheart, Kevin Noonan. I love the story about how he gave you a rose every day for the first month you were dating—and you later found out the roses had come from your aunt's garden. You divorced in 1983 and remain friends. Why did it end, do you think?

SS: When you marry young, you run the risk that you'll grow in different directions. I was completely consumed with work when I started as a D.A. in Manhattan, and I really wasn't paying attention to [my husband]. I take full responsibility for that part of the end. But he also, as he later explained to me, began to fear not being as successful as I was. And that led him to think, "Does she really need me?" I loved him and I knew he loved me. But did I need him in the way he wanted me to need him? He was probably right that I didn't.

O: Men, as a rule, want to be needed in the way he's talking about. And I think it takes a special kind of man to be with a woman like you.

SS: I fear, yes.

O: So, next question, how does one date when one is a Supreme Court justice?

SS: I have no idea, because I haven't been able to since I became one!

O: Talk about intimidating—good Lord! Lots of women—from Gayle to other friends—say, "Am I intimidating to men?" But when you're a Supreme Court justice, that's pretty damn intimidating!

SS: I worry about that, let me tell you. Since I was nominated and confirmed, I've been completely drowning in my work. But at some point I'll pick up my head and say, "It's time to date again." When I do that, you've got to find the guy for me.

O: You gotta get in line with a long list of women! [Laughs.]

GAYLE KING: [Off to the side, listening.] Get behind me, Justice!

O: Do you and the other justices hang out? Do justices hang?

SS: Well, we don't go to a local bar on Fridays and drink the night away. But we spend a lot of time together during the workweek. Not only are we in court all the time, we have lunch together, we attend a lot of dinners—I spend more time with my justice friends than I've ever spent with other colleagues. We do socialize. My colleagues like the opera; I'm more of a jazz fanatic. But occasionally we play cards together. So yes, we do hang out, just in a quieter way.

O: What is a typical day like?

SS: Boy, would it be boring for most people! It involves research, thinking, and writing. We write all the time, whether it's opinions or memos to our colleagues on legal issues that we're discussing, trying to persuade the others to change their minds—and sometimes being successful.

O: Is this the most fun you've ever had, being on the Supreme Court? Is it everything you imagined it to be?

SS: [Pauses.] No. I loved my life as a district court and circuit court judge. There, I could be more me. I could go out with friends and not think twice about it. Some of my girlfriends could tell those stories. I won't let them, but—

O: You could go dancing and take off your shoes if you wanted to.

SS: And nobody took pictures. Nobody cared. And I loved my work then. That's not to suggest I'm unhappy now. It's a wonderful life and I'm doing things I never imagined and providing an example that I never thought people would find useful. And that's important. I don't want it to sound as if I'm ungrateful, because I'm not. I'm very, very grateful. But you asked me a particular question—

O: Is this the most fun you've ever had?

SS: And the answer, truthfully, is no. The life I gave up was the most fun I ever had.

O: So what becomes your greatest aspiration when you sit on the highest court in the land?

SS: I've gone further than I ever dreamed. I'm not applying for another job for the rest of my life. You couldn't get me to go through another confirmation hearing for anything. I don't have a professional aspiration. But I do have a personal one: I want to continue growing as a person. I want to reach out more to people, learn more from them. Ultimately, I would like to be a great justice that people remember with respect and fondness. Decisions are meaningful, and I hope I write some that will last through the ages. But I hope that I'm remembered by others because I touched them in a meaningful way.

O: Have you ever made a decision from the bench and then later thought differently about it?

SS: Yes. I had a couple of cases as a judge on the trial bench where I imposed sentences and later regretted I hadn't imposed lighter ones.

O: Any other regrets?

SS: I don't remember telling my father I loved him. And I wish I had.

O: Thank you for this time, Justice. It's been an honor.

More Interviews from Oprah

SS: I love Carlos.

O: He said that you carry the hopes and aspirations of more than 50 million people. That's a lot of pressure. Do you feel that?

SS: Yes.

O: You do.

SS: I didn't think I would. Mostly because at first, I didn't think it was true. I didn't understand it until after I became a justice. Now when I talk to kids, I often tell them, "I'm going to disappoint you someday. I won't be worth my salt as a judge if I don't render at least one decision that makes you unhappy. Because if I'm following the law—and I don't write them—there has to be some decision you won't like. Please don't judge any person by one act. Take from them the good and don't concentrate on the little things that make you unhappy." That's my approach to family and friends, too.

O: You write in your book about your marriage, after you graduated Princeton, to your high school sweetheart, Kevin Noonan. I love the story about how he gave you a rose every day for the first month you were dating—and you later found out the roses had come from your aunt's garden. You divorced in 1983 and remain friends. Why did it end, do you think?

SS: When you marry young, you run the risk that you'll grow in different directions. I was completely consumed with work when I started as a D.A. in Manhattan, and I really wasn't paying attention to [my husband]. I take full responsibility for that part of the end. But he also, as he later explained to me, began to fear not being as successful as I was. And that led him to think, "Does she really need me?" I loved him and I knew he loved me. But did I need him in the way he wanted me to need him? He was probably right that I didn't.

O: Men, as a rule, want to be needed in the way he's talking about. And I think it takes a special kind of man to be with a woman like you.

SS: I fear, yes.

O: So, next question, how does one date when one is a Supreme Court justice?

SS: I have no idea, because I haven't been able to since I became one!

O: Talk about intimidating—good Lord! Lots of women—from Gayle to other friends—say, "Am I intimidating to men?" But when you're a Supreme Court justice, that's pretty damn intimidating!

SS: I worry about that, let me tell you. Since I was nominated and confirmed, I've been completely drowning in my work. But at some point I'll pick up my head and say, "It's time to date again." When I do that, you've got to find the guy for me.

O: You gotta get in line with a long list of women! [Laughs.]

GAYLE KING: [Off to the side, listening.] Get behind me, Justice!

O: Do you and the other justices hang out? Do justices hang?

SS: Well, we don't go to a local bar on Fridays and drink the night away. But we spend a lot of time together during the workweek. Not only are we in court all the time, we have lunch together, we attend a lot of dinners—I spend more time with my justice friends than I've ever spent with other colleagues. We do socialize. My colleagues like the opera; I'm more of a jazz fanatic. But occasionally we play cards together. So yes, we do hang out, just in a quieter way.

O: What is a typical day like?

SS: Boy, would it be boring for most people! It involves research, thinking, and writing. We write all the time, whether it's opinions or memos to our colleagues on legal issues that we're discussing, trying to persuade the others to change their minds—and sometimes being successful.

O: Is this the most fun you've ever had, being on the Supreme Court? Is it everything you imagined it to be?

SS: [Pauses.] No. I loved my life as a district court and circuit court judge. There, I could be more me. I could go out with friends and not think twice about it. Some of my girlfriends could tell those stories. I won't let them, but—

O: You could go dancing and take off your shoes if you wanted to.

SS: And nobody took pictures. Nobody cared. And I loved my work then. That's not to suggest I'm unhappy now. It's a wonderful life and I'm doing things I never imagined and providing an example that I never thought people would find useful. And that's important. I don't want it to sound as if I'm ungrateful, because I'm not. I'm very, very grateful. But you asked me a particular question—

O: Is this the most fun you've ever had?

SS: And the answer, truthfully, is no. The life I gave up was the most fun I ever had.

O: So what becomes your greatest aspiration when you sit on the highest court in the land?

SS: I've gone further than I ever dreamed. I'm not applying for another job for the rest of my life. You couldn't get me to go through another confirmation hearing for anything. I don't have a professional aspiration. But I do have a personal one: I want to continue growing as a person. I want to reach out more to people, learn more from them. Ultimately, I would like to be a great justice that people remember with respect and fondness. Decisions are meaningful, and I hope I write some that will last through the ages. But I hope that I'm remembered by others because I touched them in a meaningful way.

O: Have you ever made a decision from the bench and then later thought differently about it?

SS: Yes. I had a couple of cases as a judge on the trial bench where I imposed sentences and later regretted I hadn't imposed lighter ones.

O: Any other regrets?

SS: I don't remember telling my father I loved him. And I wish I had.

O: Thank you for this time, Justice. It's been an honor.

More Interviews from Oprah