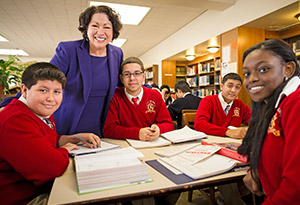

Oprah Talks to Sonia Sotomayor

Photo: Rob Howard

PAGE 3

O: You pose a question in your book that I want to ask you: How is it that some people are faced with adversity and it makes them want to rise to the highest part of themselves, and other people, faced with the same adversity, get knocked down? Is that nature or nurture?

SS: I think it's a combination of the two. There are people who really don't respond to competition, who viscerally recoil from it. And then there are people for whom it sets their spirits on fire. I do think that the nurturing gives you the confidence to have optimism. And to try things even when there's a risk of failure. One of the conversations I often have with kids is, Look, you're going to experience failure; we all have. The test of your character is how often you get up and try again.

O: Your father died when you were almost 9 years old. Afterward, your mother went into a dreadful period of mourning, which you didn't understand because they'd argued all the time. You'd assumed in some ways that things would get easier after he died.

SS: I didn't grow up understanding that my mom and dad had actually loved each other. So I couldn't make sense of her grief. I thought they'd just married because my mother needed a place to live after she left the WACs [the Women's Army Corps, with which she'd left Puerto Rico in 1944]. It wasn't until I started writing this book—and it's been one of the great gifts of writing this book—that I found a father I never knew. I learned that he and my mother had actually had a romance. When I sat down with my mother and shared my own impressions, she'd say, "Sonia, that's wrong."

O: Because all you'd seen as a child was their unhappiness. She wouldn't even come home. She was working nights at a hospital....

SS: She did everything she could to escape. And that meant, I felt, abandoning us to my dad. I could forgive my father for his drinking, because I understood it was an addiction and outside his control. I found it harder to forgive my mother—I expected more from her.

O: You write that even when she was home, and you shared a bed with her, it was like lying next to a log. She'd turn her back to you at night, cold and distant.

SS: You know, writing about personal moments like that is very, very difficult. But what I wanted was to give anyone who reads the book who has ever felt completely alone in the world—I wanted to give them hope.

O: How long were you angry with her? When did you start to soften and forgive?

SS: Well, some of it started once I began to come out of myself. I'd been very, very withdrawn for most of my life. I think that comes from having an alcoholic father—no one was welcome in my house; no one wanted to be there. As a result, my brother, Junior [now a doctor near Syracuse], and I were alone a lot. I was probably in my 30s before I began to realize that I didn't like being alone all that much, and I wanted to have more warmth in my life. So I started asking all the kids I knew, relatives and godchildren—I said, "I'm missing something really important. Nobody hugs me. Would you agree to give me a hug when you see me?" Every single one readily agreed, and they still do.

O: You have no children, but you have five godchildren.

SS: Actually, now I have six! I just baptized one a week ago.

O: Congratulations! So you went out consciously seeking the love and affection that you did not have.

SS: And learning how to give it. That's when things really started to thaw between my mother and me. When my mom met Michelle Obama, she gave the First Lady a hug. That just goes to show how we've both warmed! Now I don't think there is a friend or anyone else in my life who doesn't know how much I adore my mother and how proud I am of her and how extraordinary she is. But we're both frail human beings. Everyone makes mistakes. None of us have the tools to manage every situation that's thrown at us.

Next: What her mother did right

SS: I think it's a combination of the two. There are people who really don't respond to competition, who viscerally recoil from it. And then there are people for whom it sets their spirits on fire. I do think that the nurturing gives you the confidence to have optimism. And to try things even when there's a risk of failure. One of the conversations I often have with kids is, Look, you're going to experience failure; we all have. The test of your character is how often you get up and try again.

O: Your father died when you were almost 9 years old. Afterward, your mother went into a dreadful period of mourning, which you didn't understand because they'd argued all the time. You'd assumed in some ways that things would get easier after he died.

SS: I didn't grow up understanding that my mom and dad had actually loved each other. So I couldn't make sense of her grief. I thought they'd just married because my mother needed a place to live after she left the WACs [the Women's Army Corps, with which she'd left Puerto Rico in 1944]. It wasn't until I started writing this book—and it's been one of the great gifts of writing this book—that I found a father I never knew. I learned that he and my mother had actually had a romance. When I sat down with my mother and shared my own impressions, she'd say, "Sonia, that's wrong."

O: Because all you'd seen as a child was their unhappiness. She wouldn't even come home. She was working nights at a hospital....

SS: She did everything she could to escape. And that meant, I felt, abandoning us to my dad. I could forgive my father for his drinking, because I understood it was an addiction and outside his control. I found it harder to forgive my mother—I expected more from her.

O: You write that even when she was home, and you shared a bed with her, it was like lying next to a log. She'd turn her back to you at night, cold and distant.

SS: You know, writing about personal moments like that is very, very difficult. But what I wanted was to give anyone who reads the book who has ever felt completely alone in the world—I wanted to give them hope.

O: How long were you angry with her? When did you start to soften and forgive?

SS: Well, some of it started once I began to come out of myself. I'd been very, very withdrawn for most of my life. I think that comes from having an alcoholic father—no one was welcome in my house; no one wanted to be there. As a result, my brother, Junior [now a doctor near Syracuse], and I were alone a lot. I was probably in my 30s before I began to realize that I didn't like being alone all that much, and I wanted to have more warmth in my life. So I started asking all the kids I knew, relatives and godchildren—I said, "I'm missing something really important. Nobody hugs me. Would you agree to give me a hug when you see me?" Every single one readily agreed, and they still do.

O: You have no children, but you have five godchildren.

SS: Actually, now I have six! I just baptized one a week ago.

O: Congratulations! So you went out consciously seeking the love and affection that you did not have.

SS: And learning how to give it. That's when things really started to thaw between my mother and me. When my mom met Michelle Obama, she gave the First Lady a hug. That just goes to show how we've both warmed! Now I don't think there is a friend or anyone else in my life who doesn't know how much I adore my mother and how proud I am of her and how extraordinary she is. But we're both frail human beings. Everyone makes mistakes. None of us have the tools to manage every situation that's thrown at us.

Next: What her mother did right