Misguided in America

On April 4, 2007, radio talk show host Don Imus went on the air and called the Rutgers University women's basketball players "nappy-headed hos." Those three words stirred up a firestorm of controversy and led to the cancellation of his radio show...but the debate didn't end there.

Imus's remark opened the door for a national discussion that Oprah says she's wanted to have for years. During two special shows, Oprah brought together writers, thinkers and hip-hop industry executives to discuss the use of sexist and racist language in music and media.

A few days later, music executive Russell Simmons released a statement on behalf of the Hip-Hop Action Network calling for a ban of the words ho, bitch and the n-word from music that's played on the radio. The Reverend Al Sharpton also took action. He led a march to the top three record companies in New York City and protested the use of offensive language.

Oprah says these actions are a step in the right direction, but there are still important questions that need to be addressed. "What is at the heart of all of this?" she asks. "How do we begin to change the landscape for millions of American children who are growing up without fathers and many without any positive role models in their lives?"

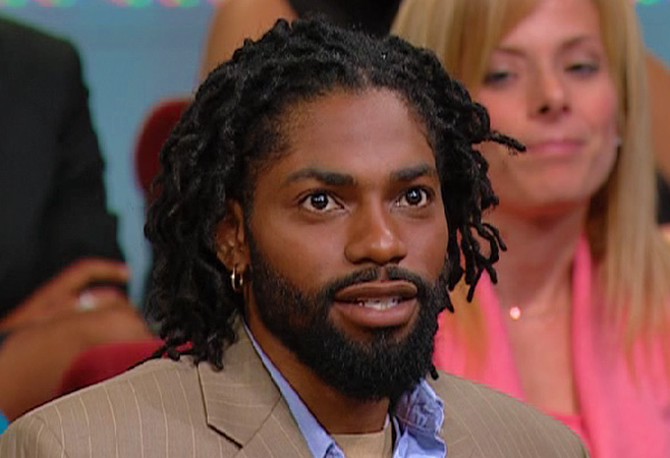

Some people are stepping up and making a difference in the lives of America's youth. Hill Harper, an actor on the hit TV show CSI: New York, is one of them. Before becoming an actor, Hill graduated magna cum laude from Brown University and earned both a master's and a law degree from Harvard.

Now, he's using his intelligence and life experiences to help young men everywhere. In his award-winning book, Letters to a Young Brother, Hill shares practical advice and stresses the importance of education.

Imus's remark opened the door for a national discussion that Oprah says she's wanted to have for years. During two special shows, Oprah brought together writers, thinkers and hip-hop industry executives to discuss the use of sexist and racist language in music and media.

A few days later, music executive Russell Simmons released a statement on behalf of the Hip-Hop Action Network calling for a ban of the words ho, bitch and the n-word from music that's played on the radio. The Reverend Al Sharpton also took action. He led a march to the top three record companies in New York City and protested the use of offensive language.

Oprah says these actions are a step in the right direction, but there are still important questions that need to be addressed. "What is at the heart of all of this?" she asks. "How do we begin to change the landscape for millions of American children who are growing up without fathers and many without any positive role models in their lives?"

Some people are stepping up and making a difference in the lives of America's youth. Hill Harper, an actor on the hit TV show CSI: New York, is one of them. Before becoming an actor, Hill graduated magna cum laude from Brown University and earned both a master's and a law degree from Harvard.

Now, he's using his intelligence and life experiences to help young men everywhere. In his award-winning book, Letters to a Young Brother, Hill shares practical advice and stresses the importance of education.

For years, Hill says he's received hundreds of letters and e-mails from young men who want to make something of themselves but aren't sure how.

Recently, he received a packet of letters from juvenile inmates at the Orange County Jail in Orlando, Florida, who had read his book. Hill decided to travel to Orlando to answer their questions in person.

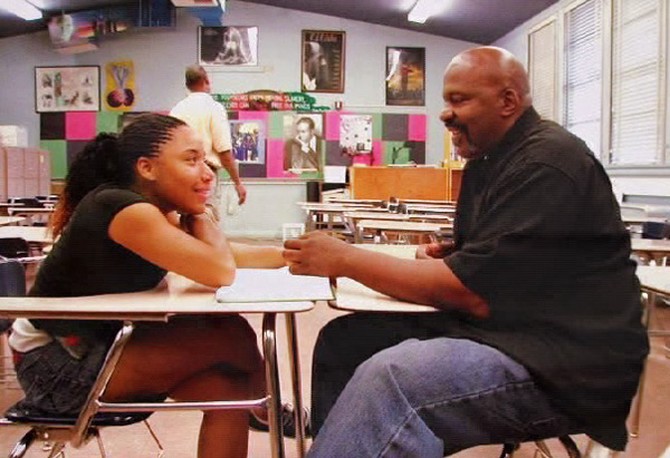

Hill meets with 29 inmates who are awaiting trial. All the men are 17 years old and younger. First, Hill leads a group discussion. Then he goes one-on-one with each boy.

Damon, a 16-year-old who is accused of armed robbery, tells Hill how his words have influenced him. "The minute I read the book, I looked at myself differently in, like, many ways," he says.

At the beginning of the day, all of the boys share their goals with Hill...except one. Travis, a 15-year-old inmate who's been charged with first-degree attempted murder, tells Hill he's lost hope. "I felt like my dream's been crushed a long time ago...ever since the first time I went to jail," he says. "I cannot find a person that can really help me to get where I'm trying to go."

By the end of their session, Hill says Travis had a change of heart and now has a dream for his future.

Recently, he received a packet of letters from juvenile inmates at the Orange County Jail in Orlando, Florida, who had read his book. Hill decided to travel to Orlando to answer their questions in person.

Hill meets with 29 inmates who are awaiting trial. All the men are 17 years old and younger. First, Hill leads a group discussion. Then he goes one-on-one with each boy.

Damon, a 16-year-old who is accused of armed robbery, tells Hill how his words have influenced him. "The minute I read the book, I looked at myself differently in, like, many ways," he says.

At the beginning of the day, all of the boys share their goals with Hill...except one. Travis, a 15-year-old inmate who's been charged with first-degree attempted murder, tells Hill he's lost hope. "I felt like my dream's been crushed a long time ago...ever since the first time I went to jail," he says. "I cannot find a person that can really help me to get where I'm trying to go."

By the end of their session, Hill says Travis had a change of heart and now has a dream for his future.

Hill says it's time to rethink the way we talk to children about their education. "We always tell kids, 'Go to school, go to school, go to school,' but we never tell them why," he says. "The answer is you talk about building a foundation. ... These young people are never taught about journey. They're never taught about going from here to there and where education fits in that piece of the journey."

As a volunteer with Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, Hill says anyone can help a child build a stronger foundation by becoming a mentor. "Mentoring is the key," he says. "All data suggests that across income, across race, that for a young man, if he has a positive male role model in his life, his chances for success and educational achievement far outweigh those that don't."

You don't have to be a Big Brother or Big Sister to make an impact—you can change lives in many different ways. "Mentorship on paper works," Hill says. "Mentorship online and technology works. Mentorship works because they just want answers...how do they navigate this journey from boyhood to manhood?"

As a volunteer with Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, Hill says anyone can help a child build a stronger foundation by becoming a mentor. "Mentoring is the key," he says. "All data suggests that across income, across race, that for a young man, if he has a positive male role model in his life, his chances for success and educational achievement far outweigh those that don't."

You don't have to be a Big Brother or Big Sister to make an impact—you can change lives in many different ways. "Mentorship on paper works," Hill says. "Mentorship online and technology works. Mentorship works because they just want answers...how do they navigate this journey from boyhood to manhood?"

Most people have never heard of Geoffrey Canada, but in one of New York City's poorest neighborhoods, he has become a household name.

In 1970, Geoffrey founded Harlem Children's Zone, a nonprofit, community-based organization that set out to prove that poor black children can and do succeed. Over the past two decades, Geoffrey has adopted a 100-block area of central Harlem and created programs to help more than 10,000 inner-city children each year.

As one of four boys raised in poverty by a single mother, Geoffrey says he knew as a child that there was a better way. "I thought, 'Boy, if I ever get the opportunity, I'm going to go in and I'm going to let those kids know that people really care about them,'" he says.

With generous contributions from private donors and foundations, Geoffrey raised enough money to build a $42 million, state-of-the-art middle school. The middle school is just a few blocks away from his progressive elementary school, Promise Academy.

Geoffrey's students go to class from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., and their school year stretches late into the summer. A free health clinic and free, healthy lunches are other perks available to Geoffrey's "adopted" children.

At Promise Academy, teachers start stressing the importance of college at an early age. To reinforce these ideas, the students recite self-affirming statements like, "We will go to college. We will succeed. This is our promise. This is our creed."

These breakthrough teaching methods seem to be working. "I have 160 kids currently in college," Geoffrey says. "We're about to send another 140 kids to college this year. We're building that pipeline."

In 1970, Geoffrey founded Harlem Children's Zone, a nonprofit, community-based organization that set out to prove that poor black children can and do succeed. Over the past two decades, Geoffrey has adopted a 100-block area of central Harlem and created programs to help more than 10,000 inner-city children each year.

As one of four boys raised in poverty by a single mother, Geoffrey says he knew as a child that there was a better way. "I thought, 'Boy, if I ever get the opportunity, I'm going to go in and I'm going to let those kids know that people really care about them,'" he says.

With generous contributions from private donors and foundations, Geoffrey raised enough money to build a $42 million, state-of-the-art middle school. The middle school is just a few blocks away from his progressive elementary school, Promise Academy.

Geoffrey's students go to class from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., and their school year stretches late into the summer. A free health clinic and free, healthy lunches are other perks available to Geoffrey's "adopted" children.

At Promise Academy, teachers start stressing the importance of college at an early age. To reinforce these ideas, the students recite self-affirming statements like, "We will go to college. We will succeed. This is our promise. This is our creed."

These breakthrough teaching methods seem to be working. "I have 160 kids currently in college," Geoffrey says. "We're about to send another 140 kids to college this year. We're building that pipeline."

One of Geoffrey's most popular programs in the Harlem Children's Zone is actually geared toward adults. Every Saturday morning, parents file into classrooms for Baby College. During these free parenting classes, new moms and dads learn about everything from health to early childhood development.

Geoffrey says the parents also learn how to discipline their children without spanking or hitting. "We have so many of our children who end up in foster care because their parents lost control," he says. "We figured out 30 years ago how you can raise a child without hitting, and no one's ever told these parents. They're skeptical at first, but as they begin to see it work, they say, 'You know what? Maybe you've got something there.'"

These lessons have helped transform the lives of hundreds of parents in Harlem. Darlene, a mom enrolled in Baby College, says instructors helped her develop positive parenting skills. "I would say to myself, 'How can you not hit? How can you not yell at him?'" she says. "They told us, 'Take your time and read instead of always yelling.' I started reading bedtime stories to him. Now, he reads to me. What I know is that in the future, my son's going to be somebody."

Geoffrey says the parents also learn how to discipline their children without spanking or hitting. "We have so many of our children who end up in foster care because their parents lost control," he says. "We figured out 30 years ago how you can raise a child without hitting, and no one's ever told these parents. They're skeptical at first, but as they begin to see it work, they say, 'You know what? Maybe you've got something there.'"

These lessons have helped transform the lives of hundreds of parents in Harlem. Darlene, a mom enrolled in Baby College, says instructors helped her develop positive parenting skills. "I would say to myself, 'How can you not hit? How can you not yell at him?'" she says. "They told us, 'Take your time and read instead of always yelling.' I started reading bedtime stories to him. Now, he reads to me. What I know is that in the future, my son's going to be somebody."

The thousands of children in Harlem Children's Zone are learning more than reading, writing and arithmetic. Geoffrey has created programs to expose his students to everything from chess to martial arts and the violin. He even partnered with Lehman Brothers to teach kids how to invest in the stock market. In one year, the students made $14,000, which they split amongst themselves.

"[Some] kids grow up thinking the whole world revolves around playing basketball or jumping rope," he says. "Our job is to say, 'There are lots of opportunities out there you don't know about.'"

What's the promise Geoffrey has made to every child he works with? "We tell our children, and we tell our parents, 'You stay with us. You work with us. You don't give up on us. We won't give up on you,'" he says. "I will promise that your child will not only go to college, but we will get that child through college."

Geoffrey says he's determined to turn things around for America's youth before they get worse.

"I'm getting to the age where I say, 'If I can't bring a change now, I'm going to leave here and leave the world worse than when I came in it,'" he says. "My parents were part of the civil rights movement. They struggled. They tried to give us a chance, and we can't drop the ball right now."

"[Some] kids grow up thinking the whole world revolves around playing basketball or jumping rope," he says. "Our job is to say, 'There are lots of opportunities out there you don't know about.'"

What's the promise Geoffrey has made to every child he works with? "We tell our children, and we tell our parents, 'You stay with us. You work with us. You don't give up on us. We won't give up on you,'" he says. "I will promise that your child will not only go to college, but we will get that child through college."

Geoffrey says he's determined to turn things around for America's youth before they get worse.

"I'm getting to the age where I say, 'If I can't bring a change now, I'm going to leave here and leave the world worse than when I came in it,'" he says. "My parents were part of the civil rights movement. They struggled. They tried to give us a chance, and we can't drop the ball right now."

We've all heard the phrase, "It takes a village to raise a child." But three high school teachers took this message to heart when confronted with low test scores in their Los Angeles school.

In 2003, Andre Chevalier, Bill Paden and Fluke Fluker decided something drastic had to be done at Cleveland High School. "The African-American students were at the bottom of the list and they were even below students that had English as a second language," Andre says. These scores, Fluke says, were not representative of the kids he taught. "We have the conversations with the kids. We know that is not a true reflection of their intelligence," Fluke says.

The teachers decided to call an emergency meeting for all the African-American students in the school to address their below-average performance. "Sometimes the truth can be brutal and so the truth for them on that particular day was showing them their test scores, and they were shocked," Fluke says.

A student named Sally says there was one word to describe what they felt at that meeting: anger. Something needed to be done. "It was really important that we showed everybody that this is not who we are," says Chris, a student.

In 2003, Andre Chevalier, Bill Paden and Fluke Fluker decided something drastic had to be done at Cleveland High School. "The African-American students were at the bottom of the list and they were even below students that had English as a second language," Andre says. These scores, Fluke says, were not representative of the kids he taught. "We have the conversations with the kids. We know that is not a true reflection of their intelligence," Fluke says.

The teachers decided to call an emergency meeting for all the African-American students in the school to address their below-average performance. "Sometimes the truth can be brutal and so the truth for them on that particular day was showing them their test scores, and they were shocked," Fluke says.

A student named Sally says there was one word to describe what they felt at that meeting: anger. Something needed to be done. "It was really important that we showed everybody that this is not who we are," says Chris, a student.

The teachers and students banded together to form a group they call the Village Nation. "The Village Nation comes from the African proverb, 'It takes a village to raise a child,'" Fluke says. "The average parent spends 12 and a half minutes face time a day with their child, and we have three or four times that amount. We began to realize that we could maybe make a difference here and do some things with these kids and, in fact, we did."

African-American teachers devoted extra time to tutoring and mentoring students, but the most important lesson the Village Nation taught was responsibility. "Here at the Village we have a chant that says, 'Am I my brother's keeper?'" Andre says. "And the students respond by saying, 'Yes, I am.' And what that means [is] that they take responsibility for their brother and for their sister."

Without that extra support, one mother says she doesn't believe her daughter would have improved. "For a while there I didn't think she would graduate," she says. "And the school here, the Village Nation, they gave her a lot of support. She's come a long ways."

"It's exciting to see that our kids, no matter what hand they're dealt, that they can do it," Andre says. "That they can fight against all the obstacles that's put before them. All that they need is an opportunity and all they need is a chance."

African-American teachers devoted extra time to tutoring and mentoring students, but the most important lesson the Village Nation taught was responsibility. "Here at the Village we have a chant that says, 'Am I my brother's keeper?'" Andre says. "And the students respond by saying, 'Yes, I am.' And what that means [is] that they take responsibility for their brother and for their sister."

Without that extra support, one mother says she doesn't believe her daughter would have improved. "For a while there I didn't think she would graduate," she says. "And the school here, the Village Nation, they gave her a lot of support. She's come a long ways."

"It's exciting to see that our kids, no matter what hand they're dealt, that they can do it," Andre says. "That they can fight against all the obstacles that's put before them. All that they need is an opportunity and all they need is a chance."

One year after the Village Nation started, test scores rose 53 points. In the past four years, test scores have continued to climb over 100 points. It didn't take extra money to get these results—all it took was thinking outside the box. "When we started this thing off, we had no indications of that type of a jump," Fluke says. "Our focus was on them making better choices, and obviously the results of the tests is a great by-product of that."

In fact, Fluke says there was almost an investigation after scores rose so much! How did they do it? "I think that what we were able to do was to create an environment where we created discipline by expectation," Bill says. "The idea that we raised the level of expectation for these kids. They went from being disinterested and uninvolved to interested and involved."

As a testament to the students' involvement, California recently made Cleveland High School a California Distinguished School—the highest award possible in the state!

In fact, Fluke says there was almost an investigation after scores rose so much! How did they do it? "I think that what we were able to do was to create an environment where we created discipline by expectation," Bill says. "The idea that we raised the level of expectation for these kids. They went from being disinterested and uninvolved to interested and involved."

As a testament to the students' involvement, California recently made Cleveland High School a California Distinguished School—the highest award possible in the state!

The Village Nation isn't just about raising test scores. It's about breaking down barriers. Bill, Andre and Fluke recently held an in-your-face assembly about using the word "nigger." As the students file into the room, the teachers refer to them using the term. Although some students said they had called each other the word, they were shocked to hear it from their teachers.

Bill helps the students understand the history and context of the word. "We all used to be somebody's niggers. That's my problem. See? And so to be out on the avenue meant you had to have permission, nigger. You had to have a note," Bill says. "I don't like the word at all because that's not what I'm about. In fact, my goal personally is to remove it from the lexicon. From the everyday language."

Bill feels the assembly was successful. "I think that these kids haven't thought about the use of the word," Bill says. "So I think it's important that we provided this kind of context for all of the young people that we are in contact with, and I think it does make a difference."

If there's one message Bill hopes others take away from the Village Nation, it's to not underestimate young people. "I don't think that we talk to young people enough. I don't think we engage them in intellectual dialogue enough," he says. "I think the more you engage young people and give them an opportunity to actually critically analyze and think ... you'll see a tremendous change in culture and how they think about themselves, their self-esteem, their self-respect and how they handle communication with other people. I just think we need to give them an opportunity to do that."

Bill helps the students understand the history and context of the word. "We all used to be somebody's niggers. That's my problem. See? And so to be out on the avenue meant you had to have permission, nigger. You had to have a note," Bill says. "I don't like the word at all because that's not what I'm about. In fact, my goal personally is to remove it from the lexicon. From the everyday language."

Bill feels the assembly was successful. "I think that these kids haven't thought about the use of the word," Bill says. "So I think it's important that we provided this kind of context for all of the young people that we are in contact with, and I think it does make a difference."

If there's one message Bill hopes others take away from the Village Nation, it's to not underestimate young people. "I don't think that we talk to young people enough. I don't think we engage them in intellectual dialogue enough," he says. "I think the more you engage young people and give them an opportunity to actually critically analyze and think ... you'll see a tremendous change in culture and how they think about themselves, their self-esteem, their self-respect and how they handle communication with other people. I just think we need to give them an opportunity to do that."

La'Teef Pyles, a 28-year-old barber in Atlanta, found a simple way to mentor the children who live near his business.

After seeing neighborhood children shooting hoops into makeshift goals, La'Teef set up a basketball court outside of his store. "They come to the shop every day, about 10 or 15 of them, to just play ball all day," he says. "It's an open-door policy in my barbershop. They come in and talk to me about whatever issues they have, and I just try to be somebody that listens to them and gives them positive advice."

After seeing neighborhood children shooting hoops into makeshift goals, La'Teef set up a basketball court outside of his store. "They come to the shop every day, about 10 or 15 of them, to just play ball all day," he says. "It's an open-door policy in my barbershop. They come in and talk to me about whatever issues they have, and I just try to be somebody that listens to them and gives them positive advice."

According to Diverse Issues in Higher Education, one-third of black males born today will spend time in prison. And, The Washington Post reports that 48 percent of all black children live without fathers in their home.

Susan Taylor, the driving force behind Essence magazine for the last 36 years, says she can no longer live with these statistics. "It almost reads, Oprah, like poor fiction. That in the wealthiest country in the world we have 30 million people who go to sleep hungry every night," she says. "We have failing schools, everywhere there are poor people. And what we know is that failing schools are the pipeline to prison. There is absolutely no opportunity for you if you're in a school that is not serving you well."

It's time to make a change, Susan says. Essence is teaming up with various organizations to enlist 1 million people to become mentors to struggling kids. It's called the Essence Cares Movement. "We're going to enlist a million or more people to link arms and aims, and put each hand on a vulnerable young person's shoulder. That's what we're asking," Susan says. "Women, get your men, please, to stand up and mentor, because the critical need is really for men."

To become a part of this amazing movement and to get paired up with a child who lives near you, visit Essence.com or call 914-390-2327.

Susan Taylor, the driving force behind Essence magazine for the last 36 years, says she can no longer live with these statistics. "It almost reads, Oprah, like poor fiction. That in the wealthiest country in the world we have 30 million people who go to sleep hungry every night," she says. "We have failing schools, everywhere there are poor people. And what we know is that failing schools are the pipeline to prison. There is absolutely no opportunity for you if you're in a school that is not serving you well."

It's time to make a change, Susan says. Essence is teaming up with various organizations to enlist 1 million people to become mentors to struggling kids. It's called the Essence Cares Movement. "We're going to enlist a million or more people to link arms and aims, and put each hand on a vulnerable young person's shoulder. That's what we're asking," Susan says. "Women, get your men, please, to stand up and mentor, because the critical need is really for men."

To become a part of this amazing movement and to get paired up with a child who lives near you, visit Essence.com or call 914-390-2327.

Susan and Essence are working on another effort to help children—the Essence Music Festival, a party with a purpose. The event will be held in New Orleans on July 5, 6 and 7. A portion of the proceeds will be donated to the Children's Defense Fund's Freedom Schools to help those still trying to make ends meet after Hurricane Katrina. "The people there are struggling. Come help us to bring the city back," Susan says. "We want to make sure that every child in New Orleans has an opportunity to go to a freedom school."

Whether you attend the festival or volunteer as a mentor, Susan emphasizes that making a change is very doable. "For every problem there's a solution, and we're the answer," Susan says. "Children of any race in this country, they're not doing well. And it's our responsibility as elders to first nurture ourselves. Take care of ourselves so that we bring our best selves to parenting and to mentoring. ... Let us save ourselves."

"I believe one of the most important questions any of us can ever ask of ourselves is, 'What and how can I be of service?'" Oprah says. "It doesn't take a Harvard degree or millions of dollars to make a difference in a child's life. ... It just really takes a commitment and a will to do better."

Whether you attend the festival or volunteer as a mentor, Susan emphasizes that making a change is very doable. "For every problem there's a solution, and we're the answer," Susan says. "Children of any race in this country, they're not doing well. And it's our responsibility as elders to first nurture ourselves. Take care of ourselves so that we bring our best selves to parenting and to mentoring. ... Let us save ourselves."

"I believe one of the most important questions any of us can ever ask of ourselves is, 'What and how can I be of service?'" Oprah says. "It doesn't take a Harvard degree or millions of dollars to make a difference in a child's life. ... It just really takes a commitment and a will to do better."

Published 01/01/2006