Meet the Original "Rosa Parks"

What do the following people have in common?

Christopher Columbus was not the first European to cross the Atlantic—Viking Leif Erickson did it 500 years earlier. Elvis didn't invent rock 'n' roll—Chuck Berry and Little Richard did.

And while Rosa Parks is famously remembered for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus—the act of civil disobedience that sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and eventually lead to the Supreme Court's invalidation of "separate but equal" segregation—she wasn't the first woman to challenge the segregated bus laws of Montgomery, Alabama. A 15-year-old schoolgirl had done the same thing nine months earlier.

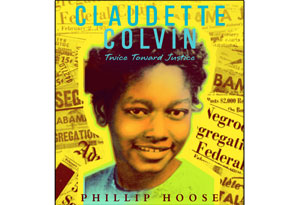

The story of that girl is told in Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, the 2009 National Book Award winner in the Young People's Lit category. Author Phillip Hoose weaves together the richly detailed memories of the now-septuagenarian Colvin into the context of the burgeoning civil rights movement and the brutal oppression of Jim Crow South that treated black Americans as second-class citizens.

But how could so few people know her story until now?

"Important things get left out," Hoose says. "And after time, maybe it's inevitable, history gets consolidated into a few characters, and any important episode gets more about a couple people as time progresses."

- Christopher Columbus

- Elvis Presley

- Rosa Parks

Christopher Columbus was not the first European to cross the Atlantic—Viking Leif Erickson did it 500 years earlier. Elvis didn't invent rock 'n' roll—Chuck Berry and Little Richard did.

And while Rosa Parks is famously remembered for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus—the act of civil disobedience that sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and eventually lead to the Supreme Court's invalidation of "separate but equal" segregation—she wasn't the first woman to challenge the segregated bus laws of Montgomery, Alabama. A 15-year-old schoolgirl had done the same thing nine months earlier.

The story of that girl is told in Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, the 2009 National Book Award winner in the Young People's Lit category. Author Phillip Hoose weaves together the richly detailed memories of the now-septuagenarian Colvin into the context of the burgeoning civil rights movement and the brutal oppression of Jim Crow South that treated black Americans as second-class citizens.

But how could so few people know her story until now?

"Important things get left out," Hoose says. "And after time, maybe it's inevitable, history gets consolidated into a few characters, and any important episode gets more about a couple people as time progresses."

On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin was just another high school junior riding the city bus home from school. When she got on, she and her friends took open seats near the front. As the bus rumbled on its route, filling with passengers, the black riders were expected to give up those seats at the front of the bus to white passengers—as the Jim Crow segregation laws of the South dictated. Claudette's friends moved, but she refused, even as the bus driver ordered her to move.

When he pulled into a terminal, the driver called for transit police. These officers boarded the bus and forcibly removed Colvin while she called out, "It's my Constitutional right!" She was arrested and, though she was a minor, held overnight in the city's adult jail.

In Twice Toward Justice, Colvin explains that she had big things on her mind the day she refused to give up her seat. "I might have considered getting up if the woman had been elderly, but she wasn't. She looked about 40. … Rebellion was on my mind that day. All during February, we'd been talking about people who had taken stands. We had been studying the Constitution in Miss Nesbitt's class. I knew I had rights. I had paid my fare the same as white passengers. I knew the rule—that you didn't have to get up for a white person if there were no empty seats left on the bus—and there weren't. … Right then I decided I wasn't gonna take it anymore. I hadn't planned it out, but my decision was built on a lifetime of nasty experiences."

In an interview, Colvin says she drew strength from history on that day. "My favorite heroes from the earlier civil rights movement were Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman," she says. "I thought about them when I was on the bus."

After her arrest, the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP and civil rights attorney E.D. Nixon thought Claudette's case would be the perfect opportunity to challenge Jim Crow laws. However, during the legal proceedings before the trial, Claudette became pregnant and Nixon decided to abandon her case. They feared the press and prosecution would seize on Claudette's pregnancy to ruin her credibility as a witness.

When Rosa Parks—who worked as a seamstress and secretary for the NAACP and raised money for Claudette's defense—later challenged the same laws by refusing to give up her seat, she became the cause célèbre that launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott and drew the support of Atlanta minister Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Hoose says Parks benefited greatly from Claudette Colvin's courage. "Rosa Parks nine months later had an awful lot of information that came from Claudette's experience—her court experience, her experience in the community, all those churches raised money for her and there had been all those meetings with the city to discuss the Colvin case," he says. "But Claudette did it cold one day."

This wasn't the end of Claudette's role in history, however. Another civil rights attorney, Fred Gray, filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Montgomery, seeking to invalidate segregation on buses. Risking very real dangers of violence, Claudette joined the case, along with three other women—Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald and Mary Louise Smith.

At the hearing, Claudette deftly fended off the aggressive questioning of a white city attorney—a practically unheard of act in a culture that expected all blacks to remain deferential to whites. "To put your name on the lawsuit and get in the paper, to testify in court against the entire Jim Crow system, was risking her life," Hoose says. "She was avoided by some her neighbors, some people were afraid of her because they were afraid there'd be violence against her."

When the decision in Browder v. Gayle arrived (and was later upheld by the Supreme Court), bus segregation and the boycott were invalidated.

When he pulled into a terminal, the driver called for transit police. These officers boarded the bus and forcibly removed Colvin while she called out, "It's my Constitutional right!" She was arrested and, though she was a minor, held overnight in the city's adult jail.

In Twice Toward Justice, Colvin explains that she had big things on her mind the day she refused to give up her seat. "I might have considered getting up if the woman had been elderly, but she wasn't. She looked about 40. … Rebellion was on my mind that day. All during February, we'd been talking about people who had taken stands. We had been studying the Constitution in Miss Nesbitt's class. I knew I had rights. I had paid my fare the same as white passengers. I knew the rule—that you didn't have to get up for a white person if there were no empty seats left on the bus—and there weren't. … Right then I decided I wasn't gonna take it anymore. I hadn't planned it out, but my decision was built on a lifetime of nasty experiences."

In an interview, Colvin says she drew strength from history on that day. "My favorite heroes from the earlier civil rights movement were Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman," she says. "I thought about them when I was on the bus."

After her arrest, the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP and civil rights attorney E.D. Nixon thought Claudette's case would be the perfect opportunity to challenge Jim Crow laws. However, during the legal proceedings before the trial, Claudette became pregnant and Nixon decided to abandon her case. They feared the press and prosecution would seize on Claudette's pregnancy to ruin her credibility as a witness.

When Rosa Parks—who worked as a seamstress and secretary for the NAACP and raised money for Claudette's defense—later challenged the same laws by refusing to give up her seat, she became the cause célèbre that launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott and drew the support of Atlanta minister Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Hoose says Parks benefited greatly from Claudette Colvin's courage. "Rosa Parks nine months later had an awful lot of information that came from Claudette's experience—her court experience, her experience in the community, all those churches raised money for her and there had been all those meetings with the city to discuss the Colvin case," he says. "But Claudette did it cold one day."

This wasn't the end of Claudette's role in history, however. Another civil rights attorney, Fred Gray, filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Montgomery, seeking to invalidate segregation on buses. Risking very real dangers of violence, Claudette joined the case, along with three other women—Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald and Mary Louise Smith.

At the hearing, Claudette deftly fended off the aggressive questioning of a white city attorney—a practically unheard of act in a culture that expected all blacks to remain deferential to whites. "To put your name on the lawsuit and get in the paper, to testify in court against the entire Jim Crow system, was risking her life," Hoose says. "She was avoided by some her neighbors, some people were afraid of her because they were afraid there'd be violence against her."

When the decision in Browder v. Gayle arrived (and was later upheld by the Supreme Court), bus segregation and the boycott were invalidated.

Colvin's memory not only of facts of her life, but also how she felt at the time, shakes readers into fully understanding the dehumanizing effects of Jim Crow. How is she able to summon such details more than 55 years later? Simple, her family never let her forget them. "When we had family reunions, we'd talk about it," Colvin says. "The good and the bad."

Hoose says recording Colvin's emotional memory of both the Jim Crow era and her stand against it was his mission as a historian. "What it felt like, how angering and raw and humiliating it could be if you let it really get to you," he says. "She told stories that I put in the book that make me so mad to hear them. When she would go to buy shoes downtown, her mother would have to trace the shape of her shoe on a paper sack and Claudette would carry that sack downtown with the outline of her foot, because they wouldn't let her try the shoes on."

After her heroic stand, Colvin faded from the historical memory. She moved to New York City, eventually settling into the rhythms of family and the anonymity of work in a nursing home. In 1995, a reporter named Richard Willing wrote a piece about Colvin in USA Today. Suddenly all her friends and co-workers knew about what she'd done four decades earlier. "They were swept off their feet. They didn't realize," she says. "One girl in the locker room, she almost knocked me on the floor."

But no article can tell the full story of Colvin's stand. While working on We Were There, Too!, a book about the too often ignored contributions of children throughout American history, Hoose kept hearing people mention Claudette's story. When he started researching it, he found some brief mentions of her in various books about the civil rights movement, but they tended to be either dismissive of her personal protest or represented her as a wild and uncontrollable teenager. "She was in danger of being forgotten, but probably in greater danger of being unfairly characterized throughout history, in tiny little paragraphs."

After coming across Willing's article, Hoose tried for four years to contact Colvin. "And always the message would come back: Maybe when I retire," Hoose says.

When she did retire, Colvin agreed to allow Hoose to write her story—on one condition. She wanted him to write the book in such a way that it would be put in schools for children to hear her story. "My reason wasn't seeking notoriety," she says. "My reason was wanting the young people to know the struggles and appreciate the civil rights movement."

"I'm very, very happy that her story has attracted this much attention. I think it'll make it impossible to tell the story of the Montgomery bus protest in the same way," Hoose says. "Our lives are changed because of things this 15-year-old girl did."

Are you inspired by Claudette's courage? What other women in history have empowered you? Share your comments below.

Hoose says recording Colvin's emotional memory of both the Jim Crow era and her stand against it was his mission as a historian. "What it felt like, how angering and raw and humiliating it could be if you let it really get to you," he says. "She told stories that I put in the book that make me so mad to hear them. When she would go to buy shoes downtown, her mother would have to trace the shape of her shoe on a paper sack and Claudette would carry that sack downtown with the outline of her foot, because they wouldn't let her try the shoes on."

After her heroic stand, Colvin faded from the historical memory. She moved to New York City, eventually settling into the rhythms of family and the anonymity of work in a nursing home. In 1995, a reporter named Richard Willing wrote a piece about Colvin in USA Today. Suddenly all her friends and co-workers knew about what she'd done four decades earlier. "They were swept off their feet. They didn't realize," she says. "One girl in the locker room, she almost knocked me on the floor."

But no article can tell the full story of Colvin's stand. While working on We Were There, Too!, a book about the too often ignored contributions of children throughout American history, Hoose kept hearing people mention Claudette's story. When he started researching it, he found some brief mentions of her in various books about the civil rights movement, but they tended to be either dismissive of her personal protest or represented her as a wild and uncontrollable teenager. "She was in danger of being forgotten, but probably in greater danger of being unfairly characterized throughout history, in tiny little paragraphs."

After coming across Willing's article, Hoose tried for four years to contact Colvin. "And always the message would come back: Maybe when I retire," Hoose says.

When she did retire, Colvin agreed to allow Hoose to write her story—on one condition. She wanted him to write the book in such a way that it would be put in schools for children to hear her story. "My reason wasn't seeking notoriety," she says. "My reason was wanting the young people to know the struggles and appreciate the civil rights movement."

"I'm very, very happy that her story has attracted this much attention. I think it'll make it impossible to tell the story of the Montgomery bus protest in the same way," Hoose says. "Our lives are changed because of things this 15-year-old girl did."

Are you inspired by Claudette's courage? What other women in history have empowered you? Share your comments below.