Inside Auschwitz

At the entrance to Auschwitz, Oprah stands in the spot Elie Wiesel began his dark journey into Night. "It is right here, on this railroad track, leading into the camp," she says, "that a young teenage boy arrived in a cattle car with his family, friends and neighbors."

Up to 100 people were packed into a single car, with no food, no water, no toilet and little air. In Night, Professor Wiesel remembers his own journey.

"And we didn't listen," Professor Wiesel says. "I had a very strange idea [when I arrived at Auschwitz]. I was thinking that maybe it's the end of history, and I thought maybe it's the end of Jewish history. And then I thought maybe it means the end of times."

Up to 100 people were packed into a single car, with no food, no water, no toilet and little air. In Night, Professor Wiesel remembers his own journey.

There was a woman among us, a certain Mrs. Schächter. ... I knew her well. ... Mrs. Schächter had lost her mind. On the first day of our journey, she had already begun to moan. ... Later, her sobs and screams became hysterical. ... "Fire! I see a fire!" ... Some pressed against the bars to see. There was nothing. Only the darkness of night. ... "She is mad, poor woman..." (pp. 24–25)Days later, as young Elie Wiesel stepped off the cattle car at the Auschwitz subcamp Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II, he smelled the stench of burning human flesh and saw the crematorium throwing its flames into the sky. "[Mrs. Schächter] wasn't so mad at all," Oprah says. "She was a prophet."

"And we didn't listen," Professor Wiesel says. "I had a very strange idea [when I arrived at Auschwitz]. I was thinking that maybe it's the end of history, and I thought maybe it's the end of Jewish history. And then I thought maybe it means the end of times."

The systematic process of determining who would live and who would die was known as "selection." SS officers briefly sized up each new arrival. Those deemed capable of hard labor, like 15-year-old Elie Wiesel and his father, went into the work camp. All others were sent immediately and unknowingly down the path to Auschwitz's four gas chambers.

Those selected to die were told they were getting showers, then packed into the chambers by the thousands. Canisters of the deadly chemical Zyklon B were dropped in. As the toxic pellets mixed with air, cyanide gas was released. Death took about 15 minutes to come and felt like suffocation. Proud of their efficiency, SS officers witnessed the gassing as it happened through special peepholes.

The grisly task of burning the dead bodies in underground ovens was left to Jewish prisoners. Forced into this horrific job, they temporarily evaded their own death.

Professor Wiesel and Oprah walk to the site of crematorium number three. It is likely that his mother and younger sister, Tzipora, were murdered inside. The building now lies in ruins—destroyed by the Nazis on the eve of liberation, in a vain attempt to hide the evidence of their atrocities.

"Every step was programmed," Professor Wiesel says. "Like a scientific laboratory. And what did they achieve? Death and more death. ... A death factory."

"And we didn't listen," Professor Wiesel says. "I had a very strange idea [when I arrived at Auschwitz]. I was thinking that maybe it's the end of history, and I thought maybe it's the end of Jewish history. And then I thought maybe it means the end of times."

Those selected to die were told they were getting showers, then packed into the chambers by the thousands. Canisters of the deadly chemical Zyklon B were dropped in. As the toxic pellets mixed with air, cyanide gas was released. Death took about 15 minutes to come and felt like suffocation. Proud of their efficiency, SS officers witnessed the gassing as it happened through special peepholes.

The grisly task of burning the dead bodies in underground ovens was left to Jewish prisoners. Forced into this horrific job, they temporarily evaded their own death.

Professor Wiesel and Oprah walk to the site of crematorium number three. It is likely that his mother and younger sister, Tzipora, were murdered inside. The building now lies in ruins—destroyed by the Nazis on the eve of liberation, in a vain attempt to hide the evidence of their atrocities.

"Every step was programmed," Professor Wiesel says. "Like a scientific laboratory. And what did they achieve? Death and more death. ... A death factory."

There was a woman among us, a certain Mrs. Schächter. ... I knew her well. ... Mrs. Schächter had lost her mind. On the first day of our journey, she had already begun to moan. ... Later, her sobs and screams became hysterical. ... "Fire! I see a fire!" ... Some pressed against the bars to see. There was nothing. Only the darkness of night. ... "She is mad, poor woman..." (pp. 24–25)Days later, as young Elie Wiesel stepped off the cattle car at the Auschwitz subcamp Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II, he smelled the stench of burning human flesh and saw the crematorium throwing its flames into the sky. "[Mrs. Schächter] wasn't so mad at all," Oprah says. "She was a prophet."

"And we didn't listen," Professor Wiesel says. "I had a very strange idea [when I arrived at Auschwitz]. I was thinking that maybe it's the end of history, and I thought maybe it's the end of Jewish history. And then I thought maybe it means the end of times."

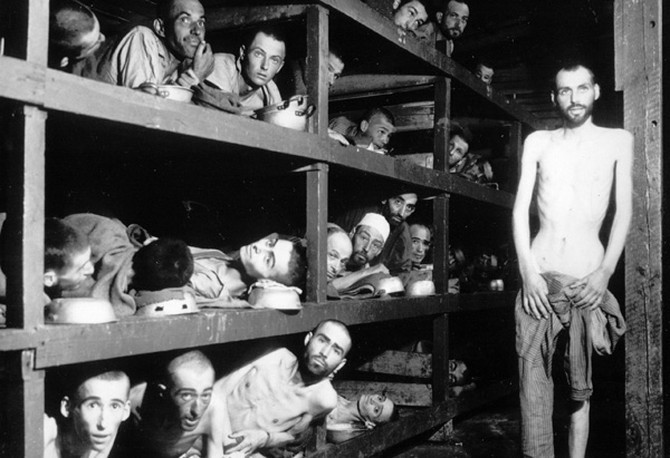

Professor Wiesel takes Oprah inside one of the few barracks still standing at Auschwitz. He says that prisoners were packed two or more to a bunk on straw mattresses. Professor Wiesel slept on similar bunks at Auschwitz and later at Buchenwald. In this photo, taken by soldiers on April 16, 1945, after the liberation of Buchewald, Elie Wiesel looks out from the far right of the middle bunk.

Rats, lice and other vermin were rampant. Deadly outbreaks of dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and malaria wiped out entire sections of this camp. Inmates wore thin cotton uniforms year round, even in the harshest winter. Given only meager rations of stale bread and meatless soup, many starved to death. For prisoners not sentenced to die in the gas chambers, the average life span was barely four months.

Rats, lice and other vermin were rampant. Deadly outbreaks of dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and malaria wiped out entire sections of this camp. Inmates wore thin cotton uniforms year round, even in the harshest winter. Given only meager rations of stale bread and meatless soup, many starved to death. For prisoners not sentenced to die in the gas chambers, the average life span was barely four months.

Professor Wiesel says it is hard for him to be back in the barracks because of the memories of those who perished inside. "When I come here, I'm not really alone. I'm with you but I'm not only with you," Professor Wiesel tells Oprah. "They are around us. ... I think of them all the time, but here even more so."

Professor Wiesel tells Oprah how he overcame insurmountable odds as they stand in front of Block 17, one of the barracks where he lived as a prisoner.

Oprah: It is just a miracle—it feels like a miracle—that you did survive.

Elie Wiesel: Believe me, Oprah, I can't understand it. I was the wrong person for it. I was always timid, frightened, bashful...I had never taken any initiative to try to live. I never pushed myself, never volunteered. I was the wrong person. I was always sick when I was a child. I got here, and if I survived this place until Buchenwald, it was because my father was alive. And I knew that if I died, he would die.

Oprah: So you stayed alive for him?

Elie Wiesel: For him.

Oprah: It is just a miracle—it feels like a miracle—that you did survive.

Elie Wiesel: Believe me, Oprah, I can't understand it. I was the wrong person for it. I was always timid, frightened, bashful...I had never taken any initiative to try to live. I never pushed myself, never volunteered. I was the wrong person. I was always sick when I was a child. I got here, and if I survived this place until Buchenwald, it was because my father was alive. And I knew that if I died, he would die.

Oprah: So you stayed alive for him?

Elie Wiesel: For him.

The entrance gate to Auschwitz I bears the German words, Arbeit Macht Frei. "'Work makes you free,'" Professor Wiesel translates. "And that is the first ironic statement ever made here."

"This iron gate is one of the most infamous symbols of evil still standing," Oprah says. "Yet as you pass through it, there is a feeling of sacredness, haunting memory—something achingly sad and holy."

"There's so much suffering here in this place, so much agony," Professor Wiesel says. "How grateful I should be that I'm here, and look—you and I are here walking, remembering, helping, thinking of what to do with our lives, with our memories. It is kind of enriching."

"This iron gate is one of the most infamous symbols of evil still standing," Oprah says. "Yet as you pass through it, there is a feeling of sacredness, haunting memory—something achingly sad and holy."

"There's so much suffering here in this place, so much agony," Professor Wiesel says. "How grateful I should be that I'm here, and look—you and I are here walking, remembering, helping, thinking of what to do with our lives, with our memories. It is kind of enriching."

At Auschwitz I, the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, known as the Angel of Death, conducted sadistic medical experiments on prisoners, infecting them with diseases, rubbing chemicals into their skin and performing crude sterilization experiments in his quest to eliminate the Jewish race by any means possible.

In Block 11 (above), the secret German police, the Gestapo, interrogated and tortured political prisoners and anyone who dared to disobey. Professor Wiesel and Oprah lay flowers at the wall where thousands of prisoners were shot and killed.

"At least they had individual deaths—even this becomes a privilege," Professor Wiesel says. "Here, actually, death was a release because it followed the torture."

In Block 11 (above), the secret German police, the Gestapo, interrogated and tortured political prisoners and anyone who dared to disobey. Professor Wiesel and Oprah lay flowers at the wall where thousands of prisoners were shot and killed.

"At least they had individual deaths—even this becomes a privilege," Professor Wiesel says. "Here, actually, death was a release because it followed the torture."

The grounds of Auschwitz house a museum of relics where evidence of the Nazi crimes against humanity is preserved behind a wall of glass. Visitors from around the world come to bear witness and pay their respects.

A case filled with empty Zyklon B cans is a haunting reminder of the poisonous gas used by the Nazis for killing prisoners on a massive scale. "When the gas chambers were full, an SS man put on the gas mask, went to the roof, opened the little window there and threw such a can into the gas chamber," Professor Wiesel explains. "Unspeakable pain and horror—that's how they were killed. Mothers and children hugging. ... The death factory became industrialized and industry worked well."

A case filled with empty Zyklon B cans is a haunting reminder of the poisonous gas used by the Nazis for killing prisoners on a massive scale. "When the gas chambers were full, an SS man put on the gas mask, went to the roof, opened the little window there and threw such a can into the gas chamber," Professor Wiesel explains. "Unspeakable pain and horror—that's how they were killed. Mothers and children hugging. ... The death factory became industrialized and industry worked well."

Before they were murdered en masse, the Jews had been told they would be resettled in Eastern Europe. The families arrived in Auschwitz with their most treasured possessions packed into suitcases. On the outside of each case, the unsuspecting owners wrote their names and dates of birth believing their things would be returned.

Piled high inside a glass case, each now ownerless suitcase is a reminder of a life lost. "Here there are rich suitcases and poor suitcases, old suitcases and new suitcases," says Professor Wiesel.

"But in one night, everybody became one," Oprah says.

Piled high inside a glass case, each now ownerless suitcase is a reminder of a life lost. "Here there are rich suitcases and poor suitcases, old suitcases and new suitcases," says Professor Wiesel.

"But in one night, everybody became one," Oprah says.

Baby clothes and shoes are all that remain of the death camp's smallest victims. Infants were killed immediately on arrival, as were the young mothers who refused to leave their children.

Mountains of shoes serve as somber evidence of Nazi war crimes. Each pair tells a story of a human being who once lived—elegant shoes, poor shoes, dancing shoes, children's shoes.

"Look how sad these shoes are, they are crying," Professor Wiesel says. "They seem to say, 'Look at me and cry.' How many Nobel Prize winners died at the age of one? Two? And whose shoes are here? One of them could have discovered the remedy for cancer, for AIDS...the great poets, the great dreamers."

"Look how sad these shoes are, they are crying," Professor Wiesel says. "They seem to say, 'Look at me and cry.' How many Nobel Prize winners died at the age of one? Two? And whose shoes are here? One of them could have discovered the remedy for cancer, for AIDS...the great poets, the great dreamers."

The Nazis went to sinister lengths to profit from the extermination of millions, and no possible resource was wasted. Human hair shorn from victims' scalps was gathered and sold to German factories to make cloth. At the time of the camp's liberation in January 1945, seven tons of hair were discovered ready to be transported for sale. In Block 4, mounds of human hair are preserved behind a glass case more than 67 feet long.

Professor Wiesel lends insight to his emotions by making an important distinction. "The anger here is in me—hate is not," he says. "I write and I teach and therefore, I believe anger must be a catalyst."

For Professor Wiesel, this will most likely be his final trip to Auschwitz. "The death of one child makes no sense," he says. "The death of millions—what sense could it make? Except for here, now we know. Whenever people could try to conduct such experiments against another people, we must be there to shout and say, 'No, we remember.'"

Read more about the Holocaust and Hitler's "Final Solution"

Get the complete reader's guide to Oprah's Book Club selection Night

For Professor Wiesel, this will most likely be his final trip to Auschwitz. "The death of one child makes no sense," he says. "The death of millions—what sense could it make? Except for here, now we know. Whenever people could try to conduct such experiments against another people, we must be there to shout and say, 'No, we remember.'"

Read more about the Holocaust and Hitler's "Final Solution"

Get the complete reader's guide to Oprah's Book Club selection Night

Published 05/24/2006