A Rwandan Survivor Reflects on the Crisis in Sudan

Abd Raouf/AP/Wide World Photos

It was with sadness, but also with joy, that I read the story of journalist Lubna al-Hussein. She's the Sudanese woman who was arrested because she wore pants in public and was imprisoned because she refused to pay a fine as a matter of principle. I felt sadness because this incident revealed that despite so many tragedies that have happened in the world with respect to the oppression of others, and despite those who have shed their blood for justice and peace, injustice is still occurring—in this case in the name of the law.

However, it is with joy that I learned of the heroism of al-Hussein, a woman who stood up for what is right and, in return, will free many who don't have a voice. It is a lesson to every woman that we should never look the other way and accept the wrongs that are perpetrated against us or against any other human being, man or woman. Al-Hussein said in one interview: "I had chosen prison, and not to pay the fine in solidarity with hundreds of other women jailed." It is a great example to all of us.

What happened to al-Hussein touches my heart because of my own story. Injustice, no matter what shape it takes, hurts in the same way. It is the same evil of hatred and oppression that disguises itself in tribes, different countries, races and religions. What happened to my tribe during the genocide in Rwanda is no different from what's happening to al-Hussein and the women in Sudan.

Before the genocide in Rwanda started, I was a college student and had everything I needed. I had an easy life and was protected by my family and friends, who loved me very much. I had never experienced tragedy before. We knew there was injustice toward my tribe, the Tutsi, but I thought that ignoring it was the best way of dealing with it.

The day her life changed forever

However, it is with joy that I learned of the heroism of al-Hussein, a woman who stood up for what is right and, in return, will free many who don't have a voice. It is a lesson to every woman that we should never look the other way and accept the wrongs that are perpetrated against us or against any other human being, man or woman. Al-Hussein said in one interview: "I had chosen prison, and not to pay the fine in solidarity with hundreds of other women jailed." It is a great example to all of us.

What happened to al-Hussein touches my heart because of my own story. Injustice, no matter what shape it takes, hurts in the same way. It is the same evil of hatred and oppression that disguises itself in tribes, different countries, races and religions. What happened to my tribe during the genocide in Rwanda is no different from what's happening to al-Hussein and the women in Sudan.

Before the genocide in Rwanda started, I was a college student and had everything I needed. I had an easy life and was protected by my family and friends, who loved me very much. I had never experienced tragedy before. We knew there was injustice toward my tribe, the Tutsi, but I thought that ignoring it was the best way of dealing with it.

The day her life changed forever

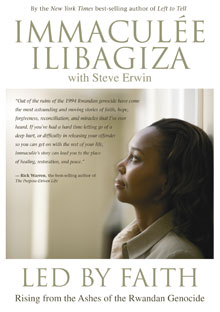

Courtesy of Hay House, Inc.

I came home for Easter holiday in April 1994, and three days later the president was killed. The government blamed the Tutsi for the assassination, and they gave orders to murder every Tutsi in the country, from babies to elders. It was an excuse. The genocide had been planned for a very a long time, and the death of the president was just a pretext to start the killings.

The government had lists of people they wanted to kill, and the whole country descended into madness. My parents were worried about me and sent me to hide at a neighbor's house, who was a member of the other tribe in Rwanda, the Hutu. They hoped that we would see each other again when the violence had died down in three or four days. The man hid me and seven other women in a small bathroom. We ended up spending three months in this small 3-by-4-foot bathroom.

During those three months, the house was constantly searched by Hutus. They were looking for Tutsis so they could kill them. It was agonizing. We were waiting to die every single day. I prayed and prayed to God to save us. If they didn't find us, it would be by his grace. After three months, the genocide was over and a million people had been killed, including my parents, my two brothers, my grandparents and many other family members and neighbors. It felt like the end of the world to me. It was unreal, and not easy to accept. I still cry to this day, but I have accepted it.

I have forgiven all the people who killed my family after a long, personal battle of rage and thoughts of hate. The thing that shocked me then, and still does today, is how damaging hatred can be. I asked myself then, "What could we have done, or not done, to avoid what occurred?" I wanted an answer. I had to find an answer, otherwise I'd have a life without hope, a life not worth living. The answer was there, as simple as can be. I thought, "If only people could have loved each other and respected each other, this would not have happened." Love is all we needed for the genocide not to be, for a million people not to die, for my parents to still be alive.

The real price of injustice

The government had lists of people they wanted to kill, and the whole country descended into madness. My parents were worried about me and sent me to hide at a neighbor's house, who was a member of the other tribe in Rwanda, the Hutu. They hoped that we would see each other again when the violence had died down in three or four days. The man hid me and seven other women in a small bathroom. We ended up spending three months in this small 3-by-4-foot bathroom.

During those three months, the house was constantly searched by Hutus. They were looking for Tutsis so they could kill them. It was agonizing. We were waiting to die every single day. I prayed and prayed to God to save us. If they didn't find us, it would be by his grace. After three months, the genocide was over and a million people had been killed, including my parents, my two brothers, my grandparents and many other family members and neighbors. It felt like the end of the world to me. It was unreal, and not easy to accept. I still cry to this day, but I have accepted it.

I have forgiven all the people who killed my family after a long, personal battle of rage and thoughts of hate. The thing that shocked me then, and still does today, is how damaging hatred can be. I asked myself then, "What could we have done, or not done, to avoid what occurred?" I wanted an answer. I had to find an answer, otherwise I'd have a life without hope, a life not worth living. The answer was there, as simple as can be. I thought, "If only people could have loved each other and respected each other, this would not have happened." Love is all we needed for the genocide not to be, for a million people not to die, for my parents to still be alive.

The real price of injustice

I realized that what causes genocides and wars and all types of injustice is the evil of looking at another and seeing them as less than you are. The evil to want to diminish the rights of another, to love them less, and the evil of hate that thinks that those you don't like don't deserve to live or don't deserve the freedom you wish for yourself. To make a difference and stand against evil and injustice, we must remember what W. H. Auden wrote: "We must love one another or die."

I would never want to go back to what I went through during the genocide or wish it upon anyone, but one good thing did come out of it: The people of Rwanda developed a genuine desire to work together without looking at their differences. The consequences of what occurred when the people couldn't live and work together were so horrendous that no one can bear to go back to the old ways.

I will never forget meeting the man who killed my cousins. I asked him what had happened to him, because I had known him as a friend before. He told me that he didn't know why he committed the atrocities he had and that he missed my cousins too. Baffling. And all so senseless.

As a result of what happened in 1994, the current Rwandan government wants to improve things in all areas of life, and anyone who is capable is welcome to help. Women in Rwanda today are given the chance to take part in the leadership, and Rwanda is now the leading country in the world with respect to the number of women in parliament (50 percent). They are doing a great job.

Immaculée Iligabiza is the author of the book Led by Faith from Hay House. Born in Rwanda, she lost most of her family during the 1994 genocide. Four years later, she emigrated to the United States and began working at the United Nations in New York City. She is now a full-time public speaker and writer and was awarded the Mahatma Gandhi International Award for Reconciliation and Peace 2007. She is the author, with Steve Erwin, of Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.

I would never want to go back to what I went through during the genocide or wish it upon anyone, but one good thing did come out of it: The people of Rwanda developed a genuine desire to work together without looking at their differences. The consequences of what occurred when the people couldn't live and work together were so horrendous that no one can bear to go back to the old ways.

I will never forget meeting the man who killed my cousins. I asked him what had happened to him, because I had known him as a friend before. He told me that he didn't know why he committed the atrocities he had and that he missed my cousins too. Baffling. And all so senseless.

As a result of what happened in 1994, the current Rwandan government wants to improve things in all areas of life, and anyone who is capable is welcome to help. Women in Rwanda today are given the chance to take part in the leadership, and Rwanda is now the leading country in the world with respect to the number of women in parliament (50 percent). They are doing a great job.

Immaculée Iligabiza is the author of the book Led by Faith from Hay House. Born in Rwanda, she lost most of her family during the 1994 genocide. Four years later, she emigrated to the United States and began working at the United Nations in New York City. She is now a full-time public speaker and writer and was awarded the Mahatma Gandhi International Award for Reconciliation and Peace 2007. She is the author, with Steve Erwin, of Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.