Photo: Marko Metzinger/Studio D

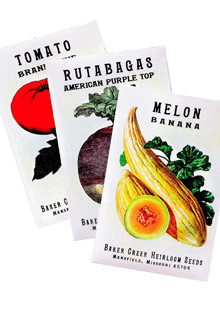

Snake melon, anyone? A Missouri couple unearths a bounty of heirloom seeds for 21st-century gardeners.

African horned cucumber. Extra long dancer snake melon. Strawberry cabbage lettuce. Brazilian oval orange eggplant. Yugoslavian finger fruit.To a real food lover, these are the sorts of adventures that set the pulse racing. What jumping off cliffs is to another kind of thrill seeker, a brand-new ingredient is to the eager cook and eater. By that standard, Jere and Emilee Gettle—a couple of 20-something homeschooled traditionalists from the Ozarks—are adding a lot of drama to America's culinary landscape. Their seed catalog, Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, offers a mind-expanding array of 1,200 fruit and vegetable varieties, many of them collected by Jere on his travels in Southeast Asia and Central America, where he's been known to cut an unfamiliar fruit open right in the marketplace and scoop out the seeds on the spot. Even if you don't garden, it's a good bet, given the explosive growth of Baker Creek's business, that some of Jere's discoveries are coming soon to a fine market or restaurant near you.

It's not just the selection that gives the Baker Street catalog its panache: Unfamiliar vegetables are styled in such a way that their colors vibrate off the page, the magenta of the moonshadow hyacinth bean set off against a blue-green leaf, the chartreuse and lime green of an artfully sliced Boule d'Or melon poised against the gray-brown of unpolished floorboards. "I ain't a really good photographer," says Jere, who has an easy, cowboyish way of expressing himself that includes a lot of ain'ts. "But I like arranging stuff. And Emilee does graphic design." This homemade publication is so gorgeous and full of personality, in fact, that it's an almost irresistible argument for putting a new experience on your plate.

Jere, who grew up in rural Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Missouri, came by his cosmopolitan interest in food naturally. "My grandparents are Spanish, German, and Mexican. We ate a lot of different kinds of things. My folks grew 15 different kinds of squashes every year." He began collecting and trading seeds the way other kids trade baseball cards, and he printed up his first seed catalog in 1998, when he was 17, growing almost all the seeds himself. Today he has a network of 50 farmers producing seeds for Baker Creek. Emilee, a Missouri native, calls herself "a garden girl all the way," though she says she wasn't really sophisticated about what she planted and cooked until she met Jere.

This is a couple who love the old-timey. Their mutual interest in history and antiques helped spark their romance, and their business includes a "pioneer village" on their farm, where they host festivals that showcase traditional crafts and folk music. It makes perfect sense that these are the people on the cutting edge of our food culture—because when it comes to fruits and vegetables, what's really new these days is the old. The revelations for cooks and eaters are generally not in the newest hybrids, engineered inevitably for large-scale production and mass-market appeal. The true discoveries lie in those open-pollinated varieties whose seeds have been saved in pockets of the planet for generations, with an eye to hardiness, vitality, and spectacular flavor.

Ask Jere why he sells only heirloom seeds, and you'll get a gust of passion: "We're saving something that Thomas Jefferson grew or that was grown by the Romans, or that was passed down in a family for 300 years, that might otherwise disappear. And it's important to maintain the genetic diversity these varieties represent. Otherwise, you have the Irish potato famine. Everybody plants the same variety and a disease comes through and wipes out the entire crop. Every one of these old-time varieties has a different flavor—and that's worth getting excited about."

The fact that the Baker Creek catalog is so panoramic is a sign of intense commitment on the part of the Gettles. "Some of the varieties we offer can't even justify the paper we use to list them, we sell so few," Jere says. "Something like wax gourds, people ain't so sure what to do with them."

Wax gourds are something I ordered for my own garden, and I'm not so sure what to do with them, either. But, Jere, on behalf of all the nation's curry experimenters and Thai soup attempters, thanks for giving us the chance to dive in and catch a thrill.

Michele Owens blogs about gardening at GardenRant.com

Back to Eating Well