Breaking Down Barriers

In 1999, Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, was the scene of one of the deadliest school shootings in United States history. Since that tragic day, hundreds of children and adults have been killed in our schools. So what's really going on in American classrooms?

Oprah Show correspondent Lisa Ling took cameras inside a typical American high school. What she found was eye-opening, and what happens proves that real change and connection is possible.

Oprah Show correspondent Lisa Ling took cameras inside a typical American high school. What she found was eye-opening, and what happens proves that real change and connection is possible.

Lisa travels to Monroe, Michigan, to meet some of the 2,000 students who attend Monroe High School. Just like almost every American high school, Monroe is divided by cliques. Assistant Principal Denise Lilly says she can identify them by simply walking through the lunchroom. "You have your athletes that sit together," Denise says. "You have your African-American students who sit together, your Latino students who sit together."

Denise says she believes a lot of the tension at Monroe is race-related. "There's a lot of racial tension in the district and in the community," she says.

According to The 2003 National School Climate Survey, more than 800,000 students are verbally harassed every year in American high schools because of their race. "Last year we had a whole bunch of fights between black people and white people," says Dorian, a junior at Monroe. "They had the police at the school."

Similar to many other schools in the country, Monroe students also cope with issues like bullying, verbal harassment and teen pregnancy.

Denise says she believes a lot of the tension at Monroe is race-related. "There's a lot of racial tension in the district and in the community," she says.

According to The 2003 National School Climate Survey, more than 800,000 students are verbally harassed every year in American high schools because of their race. "Last year we had a whole bunch of fights between black people and white people," says Dorian, a junior at Monroe. "They had the police at the school."

Similar to many other schools in the country, Monroe students also cope with issues like bullying, verbal harassment and teen pregnancy.

Monroe High School is about to undergo a major change thanks to a program called Challenge Day. In one day, Challenge Day program creators Yvonne and Rich will bring together a group of students, from all different walks of life, and help them break down their walls to create a more unified community.

Drug and alcohol abuse and bullying in schools are only symptoms of the real problems students face, Yvonne says. "The biggest problems in our schools today, we believe, are separation, isolation and loneliness," she says. "If our kids are feeling lonely, it's not because there's a lack of people. It's because there's a lack of love and connection between them."

Another major reason kids are on edge is because they often feel their parents' stress from daily life or frustrations over what it takes to raise their children.

One of the goals of Challenge Day is to work past the students' feelings of stress and isolation and help them form a bond with each other. "The kids that don't know each other from different cliques, backgrounds, belief systems, skin color...they're going to come together in here. What they're going to basically find out by the end of the day is that we're much more alike than we are different," Yvonne says.

At first, Lisa admits she was cynical about the idea. "I thought, 'Challenge Day? We're going to do something called Challenge Day?' And I kept thinking about when I was in high school and I was cynical and I thought everything was stupid," she says. "But I've got to tell you...something happened at school that day that was really remarkable."

Drug and alcohol abuse and bullying in schools are only symptoms of the real problems students face, Yvonne says. "The biggest problems in our schools today, we believe, are separation, isolation and loneliness," she says. "If our kids are feeling lonely, it's not because there's a lack of people. It's because there's a lack of love and connection between them."

Another major reason kids are on edge is because they often feel their parents' stress from daily life or frustrations over what it takes to raise their children.

One of the goals of Challenge Day is to work past the students' feelings of stress and isolation and help them form a bond with each other. "The kids that don't know each other from different cliques, backgrounds, belief systems, skin color...they're going to come together in here. What they're going to basically find out by the end of the day is that we're much more alike than we are different," Yvonne says.

At first, Lisa admits she was cynical about the idea. "I thought, 'Challenge Day? We're going to do something called Challenge Day?' And I kept thinking about when I was in high school and I was cynical and I thought everything was stupid," she says. "But I've got to tell you...something happened at school that day that was really remarkable."

Yvonne, Rich and Lisa arrive at Monroe High and begin preparations for the school's first Challenge Day. When the 64 participants walk into the gym, they immediately gravitate toward their usual cliques, sitting with people they are most comfortable with...but not for long.

"Challenge Day is a time for you to know all you've got to do is be you. Let go of any walls, any images, any masks," Yvonne tells the students. "Just be you and tell your truth...we're ready to get real."

The day begins with a variety of games that are designed to get students of different ethnicities and backgrounds to start interacting with each other. At first, some students are uneasy, but with time, the teens start opening up and eventually venture outside of their comfort zones.

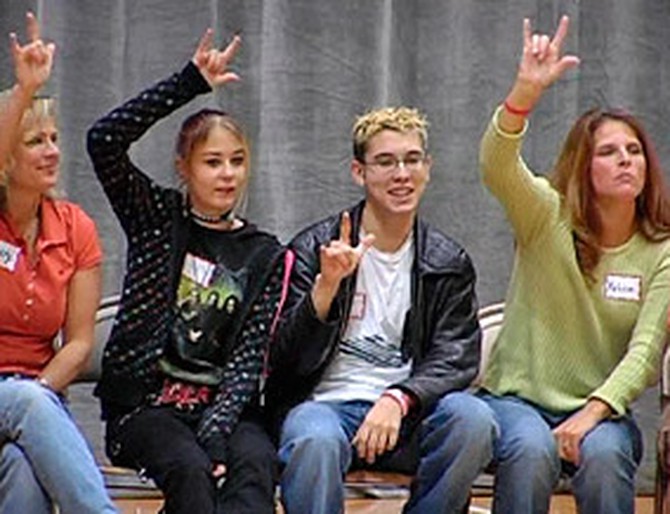

Participants also learn a silent, yet powerful, way to support one another—the "I love you" symbol in sign language. "It means, 'I've got your back,'" Yvonne says.

"It's really amazing when you actually sit across from someone, and they're divulging something very deep and very personal and when they feel most alone ... you see that sign go up, especially from a bunch of different people who you didn't interact with the day before or the week before or ever," Lisa says. "It's a pretty amazing feeling."

"Challenge Day is a time for you to know all you've got to do is be you. Let go of any walls, any images, any masks," Yvonne tells the students. "Just be you and tell your truth...we're ready to get real."

The day begins with a variety of games that are designed to get students of different ethnicities and backgrounds to start interacting with each other. At first, some students are uneasy, but with time, the teens start opening up and eventually venture outside of their comfort zones.

Participants also learn a silent, yet powerful, way to support one another—the "I love you" symbol in sign language. "It means, 'I've got your back,'" Yvonne says.

"It's really amazing when you actually sit across from someone, and they're divulging something very deep and very personal and when they feel most alone ... you see that sign go up, especially from a bunch of different people who you didn't interact with the day before or the week before or ever," Lisa says. "It's a pretty amazing feeling."

For the next challenge, Yvonne and Rich separate the students into small groups and ask them to finish the sentence, "If you really knew me, you would know that..."

At first, the students keep things very basic—talking about their hobbies, school activities and friends—but as trust begins to form and walls come down, painful secrets are revealed.

Watch students share their feelings during Challenge Day.

"If you really knew me, you'd know that when I was little, I had big huge glasses and braces," says Malayssia, a senior. "I was always called 'ugly' and I spent all of my life trying to look good for everybody so I wouldn't ever be called that again."

Lisa shares her own truth. "If you really knew me, you'd know that I was one of the only Asian kids in my school and I used to get teased all the time," she says. "Even though I was a pretty popular kid, it still was just...you know, I'd go home crying all the time."

Students open up about their feelings on academics, peer pressure and the health problems in their families. "At the beginning of the summer, [my mom] had a massive heart attack and then a triple bypass surgery...[she's] the closest person to me," says Henry, a senior. "My mom went back into the hospital last night."

At first, the students keep things very basic—talking about their hobbies, school activities and friends—but as trust begins to form and walls come down, painful secrets are revealed.

Watch students share their feelings during Challenge Day.

"If you really knew me, you'd know that when I was little, I had big huge glasses and braces," says Malayssia, a senior. "I was always called 'ugly' and I spent all of my life trying to look good for everybody so I wouldn't ever be called that again."

Lisa shares her own truth. "If you really knew me, you'd know that I was one of the only Asian kids in my school and I used to get teased all the time," she says. "Even though I was a pretty popular kid, it still was just...you know, I'd go home crying all the time."

Students open up about their feelings on academics, peer pressure and the health problems in their families. "At the beginning of the summer, [my mom] had a massive heart attack and then a triple bypass surgery...[she's] the closest person to me," says Henry, a senior. "My mom went back into the hospital last night."

An issue that many Monroe students face is racial tension. Niccole says she’s called names in the hallway and sometimes gets made fun of because of her color. "If you really knew me, [you’d know] it's hard to live in Monroe because of the racism," Niccole says. "There's a lot of it...I have to deal with people either being scared of me or hating me for being the color I am. That's a lot to deal with."

Dorian, a senior, says no one has called him names to his face, but "people have segregated me and treated me differently because of my race." He thinks most of the school's racism is under the radar. "A lot of people act like they don't see it but, yes, [it's] there," he says. "You can get it just from walking into a classroom and the teacher sees your skin color and they don't expect you to get as good as grades as another student."

Dorian, a senior, says no one has called him names to his face, but "people have segregated me and treated me differently because of my race." He thinks most of the school's racism is under the radar. "A lot of people act like they don't see it but, yes, [it's] there," he says. "You can get it just from walking into a classroom and the teacher sees your skin color and they don't expect you to get as good as grades as another student."

Another big issue in schools across the United States is bullying. Every day, more than 160,000 children miss school because they fear being bullied and teased.

Chrystal, a junior at Monroe, says she gets picked on because she dresses "goth." Sometimes she feels like she would get more respect if she dressed "preppy."

"If I'm standing in the hallway, people would actually smile and wave at me [if I dressed differently] instead of looking at me weird and calling me a 'freak' and saying rude stuff to me," she says.

Chrystal, a junior at Monroe, says she gets picked on because she dresses "goth." Sometimes she feels like she would get more respect if she dressed "preppy."

"If I'm standing in the hallway, people would actually smile and wave at me [if I dressed differently] instead of looking at me weird and calling me a 'freak' and saying rude stuff to me," she says.

Monroe students admit that gay classmates are the most bullied at school. Statistics show that bullied gay teens are six times more likely to commit suicide than straight teens.

Steven, a senior, feels the pressure of being a gay student at Monroe. "I'm openly gay here at Monroe High. Last year I got spit on. People pushed me around in the bathroom and stuff. I get made fun of all the time for being gay here," Steven says.

During Challenge Day, Steven gets a chance to address his peers...and a few bullies. "Just because I'm gay doesn't mean I'm not a person. I have the same emotions as you," he says. "There's just one thing that's different about me. Just like you're black or you're Asian or something like that."

De'lea, another openly gay senior, also shares her feelings on Challenge Day. "If you really knew me, I'm not as different as everyone thinks I am," she says. "I have stuff in common with everyone else."

Steven, a senior, feels the pressure of being a gay student at Monroe. "I'm openly gay here at Monroe High. Last year I got spit on. People pushed me around in the bathroom and stuff. I get made fun of all the time for being gay here," Steven says.

During Challenge Day, Steven gets a chance to address his peers...and a few bullies. "Just because I'm gay doesn't mean I'm not a person. I have the same emotions as you," he says. "There's just one thing that's different about me. Just like you're black or you're Asian or something like that."

De'lea, another openly gay senior, also shares her feelings on Challenge Day. "If you really knew me, I'm not as different as everyone thinks I am," she says. "I have stuff in common with everyone else."

The Monroe High students participating in Challenge Day may be different races, religions and sexual orientations, but they quickly realize they're more alike than they are different.

Yvonne gathers the students into a large group for an exercise she calls "crossing the line." If the scenario Yvonne describes applies to the students, they must cross over onto the other side of the gym.

First, Yvonne asks anyone who has ever felt alone or afraid to cross the line. Students and teachers from all backgrounds come together on the other side of the gym and put their arms around each other. "This is how easy it is for us all to be connected," Yvonne says. "There's no reason for us to do this alone."

As the exercise progresses, the scenarios get more personal. Students who have family members suffering from addiction join each other across the line. Then, those who have been hit or beaten up by loved ones are asked to step forward. "I've been hit by one of my ex-boyfriends," Chrystal says. "I know how it feels to be basically tossed aside. ... It amazed me how many people have been hit or hurt by someone that they loved."

Those who thought they were only ones dealing with difficult issues at home see that they aren't alone...some for the very first time. "You cross that line and you look to your right and left and you see people who have gone through the [same] thing," Lisa says. "Then, when you cross the line, you look out and people are giving you love. It's really emotional."

Yvonne gathers the students into a large group for an exercise she calls "crossing the line." If the scenario Yvonne describes applies to the students, they must cross over onto the other side of the gym.

First, Yvonne asks anyone who has ever felt alone or afraid to cross the line. Students and teachers from all backgrounds come together on the other side of the gym and put their arms around each other. "This is how easy it is for us all to be connected," Yvonne says. "There's no reason for us to do this alone."

As the exercise progresses, the scenarios get more personal. Students who have family members suffering from addiction join each other across the line. Then, those who have been hit or beaten up by loved ones are asked to step forward. "I've been hit by one of my ex-boyfriends," Chrystal says. "I know how it feels to be basically tossed aside. ... It amazed me how many people have been hit or hurt by someone that they loved."

Those who thought they were only ones dealing with difficult issues at home see that they aren't alone...some for the very first time. "You cross that line and you look to your right and left and you see people who have gone through the [same] thing," Lisa says. "Then, when you cross the line, you look out and people are giving you love. It's really emotional."

When Yvonne asks all the women who've been whistled at, beaten up by a man, or called a bitch, whore or slut to cross the line, every woman in the room takes a step forward.

"I've been in situations where I felt so vulnerable as a woman and I had no power," Lisa says. "Every woman has gone through it."

As the men and women face each other, Yvonne asks the men to look into the eyes of their classmates and imagine that these women are their mothers, grandmothers or sisters. Many of the men are surprised that catcalls and sexist "jokes" have had such an impact on the young women in their school.

"Watching people cry because they've been whistled at, they've been honked at...it's not funny," Charles says. "It's not fun and games."

Riley, a male student who has an older sister and was raised by a single mother, says he would never want to see his family members go through the same thing as his female classmates and teachers. "It was horrible," he says.

"I've been in situations where I felt so vulnerable as a woman and I had no power," Lisa says. "Every woman has gone through it."

As the men and women face each other, Yvonne asks the men to look into the eyes of their classmates and imagine that these women are their mothers, grandmothers or sisters. Many of the men are surprised that catcalls and sexist "jokes" have had such an impact on the young women in their school.

"Watching people cry because they've been whistled at, they've been honked at...it's not funny," Charles says. "It's not fun and games."

Riley, a male student who has an older sister and was raised by a single mother, says he would never want to see his family members go through the same thing as his female classmates and teachers. "It was horrible," he says.

As Challenge Day continues, students stop seeing each other as nerds, jocks, troublemakers and rich kids, and start seeing each other as peers.

Though most Monroe students think they know Riley, one of the "popular" students, he leaves his label at the door and opens up about a time when he wasn't so popular. "I grew up really overweight, and my mom and dad really put a lot of pressure on me to lose the weight," he says.

Then, Riley dispels a common belief that popular kids have it easy. "A lot of people judge me as somebody who has a lot of money, when in actuality, my mom is working two jobs and we're barely making it," he says. "People always place judgment on me [and] think I'm some rich, spoiled kid. I'm really not."

Ra'Shada, one of the teens labeled a "smart kid," admits that she lies about her test scores. "[My score] is a lot lower than what I say...I'm afraid that people won't think I'm smart anymore if I tell them the real score," she says.

Charles, one of Monroe High's "rich kids," says being wealthy may mean that his college tuition is paid in full, but no amount of money can protect him from his hidden pain. He reveals that after his father left his mother, his mom was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. "Every night, I [cry] myself to sleep, but I'll never let anyone see it," he says. "Every day I wake up, I'm scared. I'm scared where my life is going."

Though most Monroe students think they know Riley, one of the "popular" students, he leaves his label at the door and opens up about a time when he wasn't so popular. "I grew up really overweight, and my mom and dad really put a lot of pressure on me to lose the weight," he says.

Then, Riley dispels a common belief that popular kids have it easy. "A lot of people judge me as somebody who has a lot of money, when in actuality, my mom is working two jobs and we're barely making it," he says. "People always place judgment on me [and] think I'm some rich, spoiled kid. I'm really not."

Ra'Shada, one of the teens labeled a "smart kid," admits that she lies about her test scores. "[My score] is a lot lower than what I say...I'm afraid that people won't think I'm smart anymore if I tell them the real score," she says.

Charles, one of Monroe High's "rich kids," says being wealthy may mean that his college tuition is paid in full, but no amount of money can protect him from his hidden pain. He reveals that after his father left his mother, his mom was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. "Every night, I [cry] myself to sleep, but I'll never let anyone see it," he says. "Every day I wake up, I'm scared. I'm scared where my life is going."

As painful secrets come spilling out, Monroe High students find support from their peers and begin to make real connections, which is the ultimate goal of Challenge Day, Yvonne says.

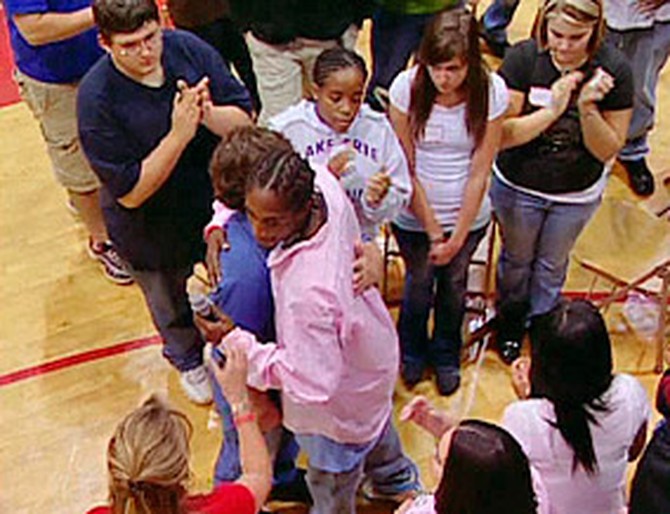

After hearing some of her classmates' heartbreaking stories, LaCrisha breaks the silence about being separated from her mother for nine years. "I come off as a person that has no problems, but when I was 8 years old, my mom left me," she says.

LaCrisha was reluctant to share her struggles with students who were strangers only hours before, but by the end of the day, she is overwhelmed by their support.

"I just want to thank everybody for being there," LaCrisha says. "Today, when one person hugged me and they told me, 'I love [you],' I really felt love for once. ... For that 30 seconds you were hugging me, I felt the most love I think I've felt in a long time."

After hearing some of her classmates' heartbreaking stories, LaCrisha breaks the silence about being separated from her mother for nine years. "I come off as a person that has no problems, but when I was 8 years old, my mom left me," she says.

LaCrisha was reluctant to share her struggles with students who were strangers only hours before, but by the end of the day, she is overwhelmed by their support.

"I just want to thank everybody for being there," LaCrisha says. "Today, when one person hugged me and they told me, 'I love [you],' I really felt love for once. ... For that 30 seconds you were hugging me, I felt the most love I think I've felt in a long time."

As barriers begin to break down, some students decide to take action.

Steven, an openly gay student, appeals to his classmates for tolerance and acceptance. "There are people in this room [who] have called me a faggot or a queer. There are a couple people that have bumped into me," he says. "I don't think you guys know how bad it hurts."

From across the room, Michael, Steven's classmate, is moved. "I remember last year seeing you in the hall and screaming out one of those names you said that hurt you every night," he says to Steven. "I had no right judging you in that way, and I just wanted to apologize. You're as equal as any of us."

Steven accepts Michael's apology, and the two young men embrace in front of their fellow students.

"I just want to say that's how we change the world—one person at a time," Oprah says. "It begins by apologizing for beliefs that have had negative influences on other people."

Steven, an openly gay student, appeals to his classmates for tolerance and acceptance. "There are people in this room [who] have called me a faggot or a queer. There are a couple people that have bumped into me," he says. "I don't think you guys know how bad it hurts."

From across the room, Michael, Steven's classmate, is moved. "I remember last year seeing you in the hall and screaming out one of those names you said that hurt you every night," he says to Steven. "I had no right judging you in that way, and I just wanted to apologize. You're as equal as any of us."

Steven accepts Michael's apology, and the two young men embrace in front of their fellow students.

"I just want to say that's how we change the world—one person at a time," Oprah says. "It begins by apologizing for beliefs that have had negative influences on other people."

On Challenge Day, the students also tackle Monroe High School's most destructive issue—racism.

Chris, a senior football player, stands before his classmates and apologizes for making racist jokes about his teammate and friend, Dorian.

"There are a lot of people in here today that I've said some things [about] that I never should have said. Nobody deserves what I said to them," he says. "I want everybody to know that I'm not going to just stop here. I'm going to go out to my family, and I'm going to let them know that racism's not where it's at. ... Today I overcame a huge hurdle in my life, and I just want everybody to know that and I'll be here for any one of you if you need me."

After receiving a hug from Dorian, Chris's African-American classmates walk up—one by one—to embrace him.

Niccole, an African-American student who experienced racism at Monroe, feels like Challenge Day helped break down some of the walls that may have contributed to the problem. "I think [students and teachers] didn't realize that it was happening. I mean, they did it, but they didn't really think about it," she says. "I think, at that point, they realized that what they say does affect what people do."

Chris, a senior football player, stands before his classmates and apologizes for making racist jokes about his teammate and friend, Dorian.

"There are a lot of people in here today that I've said some things [about] that I never should have said. Nobody deserves what I said to them," he says. "I want everybody to know that I'm not going to just stop here. I'm going to go out to my family, and I'm going to let them know that racism's not where it's at. ... Today I overcame a huge hurdle in my life, and I just want everybody to know that and I'll be here for any one of you if you need me."

After receiving a hug from Dorian, Chris's African-American classmates walk up—one by one—to embrace him.

Niccole, an African-American student who experienced racism at Monroe, feels like Challenge Day helped break down some of the walls that may have contributed to the problem. "I think [students and teachers] didn't realize that it was happening. I mean, they did it, but they didn't really think about it," she says. "I think, at that point, they realized that what they say does affect what people do."

Since Yvonne and Rich brought Challenge Day to Monroe High School, Assistant Principal Denise Lilly says student-teacher relationships have improved. "I believe that we now see each other for who we really are," she says. "It's changed us tremendously in our building."

Though Challenge Day only lasted one day, Denise says she remains committed to keeping the students connected throughout the year. "[I want] to be as pro-active as possible," she says. "[I want] to show the students that I believe it in my heart...to show them that no matter who you are, no matter what you've gone through, you are a person that needs love and needs caring."

Students, as well as administrators, have seen positive changes in the hallways of this Michigan high school. Steven, one of Monroe High’s gay students, says that since Challenge Day, classmates have stopped calling him "faggot" and some students even say "hi" when they pass by.

De'Lea, another gay student, says the experiences she had on Challenge Day have helped her open up. "I'm not so in my shell anymore. I can let people know what I'm feeling," she says. "I've made a lot of friends, and it's been a big change."

Though Challenge Day only lasted one day, Denise says she remains committed to keeping the students connected throughout the year. "[I want] to be as pro-active as possible," she says. "[I want] to show the students that I believe it in my heart...to show them that no matter who you are, no matter what you've gone through, you are a person that needs love and needs caring."

Students, as well as administrators, have seen positive changes in the hallways of this Michigan high school. Steven, one of Monroe High’s gay students, says that since Challenge Day, classmates have stopped calling him "faggot" and some students even say "hi" when they pass by.

De'Lea, another gay student, says the experiences she had on Challenge Day have helped her open up. "I'm not so in my shell anymore. I can let people know what I'm feeling," she says. "I've made a lot of friends, and it's been a big change."

Now that Monroe High School has completed the Challenge Day program, what's the next step? Yvonne says the first thing every student needs to do is stay real and vulnerable. She also suggests that every school form a team that's committed to keeping connections strong.

"Your entire goal [should be] to make sure everybody's safe, loved and celebrated," Yvonne says. "Don't stop until people are. ... Be courageous [enough] to say you're sorry—to keep looking around and loving people because that's the key."

In the years to come, Yvonne says schools like Monroe should plan a Challenge Day for an entire grade level every year. "It's kind of like a rite of passage," she says.

As these 64 students have shown, breaking down barriers and making emotional connections can make a difference. "If there's one thing that I am hoping that everybody takes from this show, it is the power of possibility and change that begins with every one of us," Oprah says.

"Your entire goal [should be] to make sure everybody's safe, loved and celebrated," Yvonne says. "Don't stop until people are. ... Be courageous [enough] to say you're sorry—to keep looking around and loving people because that's the key."

In the years to come, Yvonne says schools like Monroe should plan a Challenge Day for an entire grade level every year. "It's kind of like a rite of passage," she says.

As these 64 students have shown, breaking down barriers and making emotional connections can make a difference. "If there's one thing that I am hoping that everybody takes from this show, it is the power of possibility and change that begins with every one of us," Oprah says.

Published 11/09/2006