Photo: George Burns/Harpo Inc.

Remember your first day of school? Your first job? First kiss? From a foodie's first cooking disaster, to Barack Obama's first date with Michelle, celebrate some of life's milestone moments.

My First Date With MichelleBarack Obama, U.S. President

I met Michelle in 1988, after my first year of law school, when I took a summer job at Sidley & Austin, a law firm in Chicago. A year earlier I had been working as a community organizer in some of Chicago's poorest neighborhoods, and I struggled with the decision to go to a large firm. But with student loans mounting, the three months of salary they offered wasn't something I could pass up.

Michelle worked at Sidley, too, and, in the luckiest break of my life, was assigned to be my adviser, charged with helping me learn the ropes. I remember being struck by how tall and beautiful she was. She, I have since learned, was pleasantly surprised to see that my nose and ears weren't quite as enormous as they looked in the photo I'd submitted for the firm directory.

Over the next several weeks, we saw a lot of each other at work. She was kind enough to take me to a few parties, and never once commented on my mismatched and decidedly unstylish wardrobe.

I asked her out. She refused. I kept asking. She kept refusing.

"I'm your adviser," she said. "It's not appropriate." Finally, I offered to quit my job, and at last she relented. On our first date, I treated her to the finest ice cream Baskin-Robbins had to offer, our dinner table doubling as the curb. I kissed her, and it tasted like chocolate.

I had known those student loans were going to get me a great education, but I had no idea they'd get me my first date with the love of my life.

Get more Oprah and Michelle Obama—interviews, videos and articles

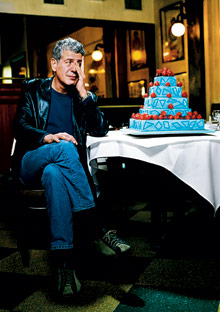

Photo: Allesandra Petlin

My First Cooking Disaster

Anthony Bourdain, chef, author and host of No Reservations

Back in the 1970s, flush with a little knowledge and a lot of youthful enthusiasm, my catering partner and I took on a new client. The job was a large wedding reception—big money—and, eager to close the deal, we had assured the customer that there was nothing we couldn't do: pâtés en croûte, truffled galantines of poultry and veal en gelée, decorative chaudfroids, whole poached salmon adorned with Escoffier-era garnishes... All these were things we could pull off with reasonable competence. So when the client inquired about a wedding cake, I didn't flinch: "Yes, of course! We'd be happy to provide a cake!"

The fact that outside of a few baking classes in culinary school, I had never in my life made any baked good, not even a from-the-mix Bundt cake, did nothing to diminish my faith in my abilities. But perhaps sensing in some dim, instinctive way that a classic, sky-high, round cake adorned with intricate pastillage work was beyond me, I opted for something different. I filled sheet pans of various sizes with batter (a recipe I'd cribbed from Julia Child). When these had baked, I stacked them in jelly-smeared layers like a Flintstones version of a Mayan temple, then iced them with buttercream that, in a disco-era moment of chemical-inspired lunacy, I'd dyed blue. For the finishing touch, I used a pastry bag to add what I believed to be avant-garde patterns of more blue icing and studded it with blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries.

My catering partner was skeptical. "It looks like Betty Crocker on acid." But it was too late to do anything else. And frankly, we thought young guns like us didn't have to follow convention—we made conventions.

We sent the cake out to the expectant crowd, where the bride and groom were poised with a knife.

Total silence.

The bride said, "Ewwww!"

The groom said, "Honey, it looks like Carvel! You like Carvel!"

And in the cold light of near-universal repulsion, I realized that I had created an abomination. I hope the happy couple is still together—though somehow I doubt it.

I never baked again.

Anthony Bourdain, chef, author and host of No Reservations

Back in the 1970s, flush with a little knowledge and a lot of youthful enthusiasm, my catering partner and I took on a new client. The job was a large wedding reception—big money—and, eager to close the deal, we had assured the customer that there was nothing we couldn't do: pâtés en croûte, truffled galantines of poultry and veal en gelée, decorative chaudfroids, whole poached salmon adorned with Escoffier-era garnishes... All these were things we could pull off with reasonable competence. So when the client inquired about a wedding cake, I didn't flinch: "Yes, of course! We'd be happy to provide a cake!"

The fact that outside of a few baking classes in culinary school, I had never in my life made any baked good, not even a from-the-mix Bundt cake, did nothing to diminish my faith in my abilities. But perhaps sensing in some dim, instinctive way that a classic, sky-high, round cake adorned with intricate pastillage work was beyond me, I opted for something different. I filled sheet pans of various sizes with batter (a recipe I'd cribbed from Julia Child). When these had baked, I stacked them in jelly-smeared layers like a Flintstones version of a Mayan temple, then iced them with buttercream that, in a disco-era moment of chemical-inspired lunacy, I'd dyed blue. For the finishing touch, I used a pastry bag to add what I believed to be avant-garde patterns of more blue icing and studded it with blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries.

My catering partner was skeptical. "It looks like Betty Crocker on acid." But it was too late to do anything else. And frankly, we thought young guns like us didn't have to follow convention—we made conventions.

We sent the cake out to the expectant crowd, where the bride and groom were poised with a knife.

Total silence.

The bride said, "Ewwww!"

The groom said, "Honey, it looks like Carvel! You like Carvel!"

And in the cold light of near-universal repulsion, I realized that I had created an abomination. I hope the happy couple is still together—though somehow I doubt it.

I never baked again.

Photo: Patrick Demarchelier

My First Job

Donna Karan, chief designer, Donna Karen International

I lied about my age. I think you had to be 16 to work, but I was 14. An old 14. I was a customer at a boutique called Shurries, in Cedarhurst, Long Island, when I said to the owner, "Listen, can I work here?"

How much money I made, I have not a clue. But I vividly remember painting the wall in the dressing room—my first major fashion illustration. It was a model walking a dog. Is it still there, that painting? God, I want it.

We had contests to see who could merchandise the floor the best—how the hangers looked, if the pants and skirts were aligned. I took pride in how neatly I kept things, but all the "put this here, put that there" was too precise for me—my ADD would kick in. My strengths were working with the customer and styling the clothes. What I became quite good at was working with younger kids; parents used to call me on my days off to come in and dress their kids. I dressed them for socials; I'd send them off to camp. If a parent wanted the child to look a certain way, I'd say, "I'll take care of this." Believe me, if you put me in another job, I'd never have that kind of confidence. In fashion I'm secure.

I learned a lot working with those teenagers at Shurries. I learned how to listen to what they felt comfortable with, and to show them how to wear clothes they thought they couldn't. (To this day, I tell all my designers that once a month they have to work in retail for a day, though nobody takes me seriously.) But my first true job—my first challenge, the first time real emotion was involved—was at Anne Klein. It started as a summer job, when I was in college. I wanted to be an illustrator, but at the interview they said I wasn't good enough and I should try designing instead. So I went to work there, and when summer ended, Anne Klein told me I didn't need to go back to school. Nine months later she fired me.

Donna Karan, chief designer, Donna Karen International

I lied about my age. I think you had to be 16 to work, but I was 14. An old 14. I was a customer at a boutique called Shurries, in Cedarhurst, Long Island, when I said to the owner, "Listen, can I work here?"

How much money I made, I have not a clue. But I vividly remember painting the wall in the dressing room—my first major fashion illustration. It was a model walking a dog. Is it still there, that painting? God, I want it.

We had contests to see who could merchandise the floor the best—how the hangers looked, if the pants and skirts were aligned. I took pride in how neatly I kept things, but all the "put this here, put that there" was too precise for me—my ADD would kick in. My strengths were working with the customer and styling the clothes. What I became quite good at was working with younger kids; parents used to call me on my days off to come in and dress their kids. I dressed them for socials; I'd send them off to camp. If a parent wanted the child to look a certain way, I'd say, "I'll take care of this." Believe me, if you put me in another job, I'd never have that kind of confidence. In fashion I'm secure.

I learned a lot working with those teenagers at Shurries. I learned how to listen to what they felt comfortable with, and to show them how to wear clothes they thought they couldn't. (To this day, I tell all my designers that once a month they have to work in retail for a day, though nobody takes me seriously.) But my first true job—my first challenge, the first time real emotion was involved—was at Anne Klein. It started as a summer job, when I was in college. I wanted to be an illustrator, but at the interview they said I wasn't good enough and I should try designing instead. So I went to work there, and when summer ended, Anne Klein told me I didn't need to go back to school. Nine months later she fired me.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First Broken Heart

David Sedaris, writer

I've never gone in for clothing with writing on it. Team jackets, T-shirts kitted out with goofy slogans—I can't even bear a discreet logo. At some point, though, I must have owned a pair of pants with KICK ME embroidered in bright letters across the ass. How else to explain "M," whom I met while in my early 20s. We worked different shifts in the same small-town restaurant, and what attracted me, aside from his looks, was an unspoken guarantee that he would never return my feelings. Unlike myself, M was sexy and popular. He liked clubs and dancing, and had once gone to Studio 54 on the arm of a wallpaper designer.

I could not have fallen for anyone more unsuitable, yet still I pursued him. We slept together only twice, and when he gave me the inevitable brush-off, I acted as though he'd ended a 30-year marriage. My crying and begging were completely uncalled for, but what really shames me are the letters I sent—60 in all. Roughly amounting to five pages for every hour we spent together, they were the ravings of a certified crazy person, and I can only hope that he threw them directly into the trash can.

A broken heart is a rite of passage and, looking back, I must have wanted one pretty badly. "Kick me," I demanded, and when somebody finally did, I burst like a cheap piñata. It's been almost 30 years since I last slept with M, but sometimes, when bending to tie my shoe, I can still feel his ghostly footprint, booting me into adulthood.

David Sedaris, writer

I've never gone in for clothing with writing on it. Team jackets, T-shirts kitted out with goofy slogans—I can't even bear a discreet logo. At some point, though, I must have owned a pair of pants with KICK ME embroidered in bright letters across the ass. How else to explain "M," whom I met while in my early 20s. We worked different shifts in the same small-town restaurant, and what attracted me, aside from his looks, was an unspoken guarantee that he would never return my feelings. Unlike myself, M was sexy and popular. He liked clubs and dancing, and had once gone to Studio 54 on the arm of a wallpaper designer.

I could not have fallen for anyone more unsuitable, yet still I pursued him. We slept together only twice, and when he gave me the inevitable brush-off, I acted as though he'd ended a 30-year marriage. My crying and begging were completely uncalled for, but what really shames me are the letters I sent—60 in all. Roughly amounting to five pages for every hour we spent together, they were the ravings of a certified crazy person, and I can only hope that he threw them directly into the trash can.

A broken heart is a rite of passage and, looking back, I must have wanted one pretty badly. "Kick me," I demanded, and when somebody finally did, I burst like a cheap piñata. It's been almost 30 years since I last slept with M, but sometimes, when bending to tie my shoe, I can still feel his ghostly footprint, booting me into adulthood.

Photo: Chris Young/WireImage.com

My First Day Off

Colin Powell, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, former secretary of state

When I retired from the army in 1993, there was a huge ceremony at Fort Myer in Virginia. President Clinton was there, as well as Vice President Gore; there were 1,000 people at the reception. I had served 35 years. I'd had a staff of 1,500. I ran wars. I commanded more than two million soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines. Now, after all those years, it was suddenly over. I was in charge of me. No more alarm clock. No more name tag. And I was ready. I was looking forward to being normal again—getting to the point where I could maybe even go to a garage sale. It's important to get back to being normal.

The first morning, I slept a little later than usual. Then I went downstairs for breakfast, and my wife, Alma, said to me, "The sink is clogged." I was delighted.

I got under the sink, took it apart, cleaned out the trap, put it back on, and made sure it didn't leak. An accomplishment.

The same thing happened after I left the State Department, when I had to replace a toilet—which, by the way, involves more than what they give you at Home Depot.

Before I decided to become a plumber, I used to rebuild Volvos. There's something invigorating about working on an engine. You know something is wrong, and by the process of elimination, you figure it out. Plumbing is the same way. You do the work, and you can test it. Either it holds water or it doesn't. The problems you deal with as chairman of the Joint Chiefs or secretary of state are usually not that amenable to rapid analysis and solution.

Colin Powell, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, former secretary of state

When I retired from the army in 1993, there was a huge ceremony at Fort Myer in Virginia. President Clinton was there, as well as Vice President Gore; there were 1,000 people at the reception. I had served 35 years. I'd had a staff of 1,500. I ran wars. I commanded more than two million soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines. Now, after all those years, it was suddenly over. I was in charge of me. No more alarm clock. No more name tag. And I was ready. I was looking forward to being normal again—getting to the point where I could maybe even go to a garage sale. It's important to get back to being normal.

The first morning, I slept a little later than usual. Then I went downstairs for breakfast, and my wife, Alma, said to me, "The sink is clogged." I was delighted.

I got under the sink, took it apart, cleaned out the trap, put it back on, and made sure it didn't leak. An accomplishment.

The same thing happened after I left the State Department, when I had to replace a toilet—which, by the way, involves more than what they give you at Home Depot.

Before I decided to become a plumber, I used to rebuild Volvos. There's something invigorating about working on an engine. You know something is wrong, and by the process of elimination, you figure it out. Plumbing is the same way. You do the work, and you can test it. Either it holds water or it doesn't. The problems you deal with as chairman of the Joint Chiefs or secretary of state are usually not that amenable to rapid analysis and solution.

Photo: Jeffery Mayer/WireImage.com

My First Love Scene (with Another Woman)

Cybill Shepherd, guest star on The L Word

I initially took the part on The L Word at the suggestion of my daughter Clementine. She said, "I think you should do this. It's important"—which is remarkable, because it's pretty embarrassing to a child to watch her mother having sex onscreen. But all my kids were supportive, so I watched a few episodes, thought the show was great, and signed on.

The L Word has a lot of sex. A lot of women having sex. With a lot of other women. (I love this. I think we need to see more beautiful women having sex!) So when I heard I was going to play Phyllis Kroll—who's been married for 25 years, has two kids, and has her first lesbian experience in her 50s—I knew what I was in for.

Getting naked on camera is deeply uncomfortable for me. The only nude scene I ever did was in my very first film, with Jeff Bridges in The Last Picture Show, and it was mortifying. I wasn't going to do a nude scene here, though—just something sensual and very, very sexy. Still, after reading the script, I was nervous. But I once got some great acting advice: If you play what you haven't lived, it will help you expand as a human being. So I sat down with the producer, the director, and Leisha Hailey, my character's love interest, and we blocked it out. I felt a tremendous chemistry with Leisha. You have to have chemistry—you can't act that. You have to be a bit turned on. And I was! I was on the set with all these beautiful women walking around. And as we rehearsed, I began to feel very comfortable. I didn't compare it to being with a man. I just didn't go there. I was focused on my character's sexual awakening. Not my own.

Cybill Shepherd, guest star on The L Word

I initially took the part on The L Word at the suggestion of my daughter Clementine. She said, "I think you should do this. It's important"—which is remarkable, because it's pretty embarrassing to a child to watch her mother having sex onscreen. But all my kids were supportive, so I watched a few episodes, thought the show was great, and signed on.

The L Word has a lot of sex. A lot of women having sex. With a lot of other women. (I love this. I think we need to see more beautiful women having sex!) So when I heard I was going to play Phyllis Kroll—who's been married for 25 years, has two kids, and has her first lesbian experience in her 50s—I knew what I was in for.

Getting naked on camera is deeply uncomfortable for me. The only nude scene I ever did was in my very first film, with Jeff Bridges in The Last Picture Show, and it was mortifying. I wasn't going to do a nude scene here, though—just something sensual and very, very sexy. Still, after reading the script, I was nervous. But I once got some great acting advice: If you play what you haven't lived, it will help you expand as a human being. So I sat down with the producer, the director, and Leisha Hailey, my character's love interest, and we blocked it out. I felt a tremendous chemistry with Leisha. You have to have chemistry—you can't act that. You have to be a bit turned on. And I was! I was on the set with all these beautiful women walking around. And as we rehearsed, I began to feel very comfortable. I didn't compare it to being with a man. I just didn't go there. I was focused on my character's sexual awakening. Not my own.

Photo: Courtesy of Fox Broadcasting

My First "D'oh!"

Dan Castellaneta, the voice of Homer Simpson

It started with the Simpsons shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show. Matt Groening directed those early sessions, and when I saw "annoyed grunt" in the script, I asked him, "What is that?" And he said, "Whatever you want it to be." Usually Matt has a very specific idea about how something should be read, but in that case he left it open. I remembered as a kid watching Laurel and Hardy movies, and there was a comedian by the name of Jim Finlayson who was their nemesis. Whenever Laurel and Hardy would frustrate him, he would go, "Doooh." And so I went, "Doooh." But because these pieces were only seconds long, Matt said, "Well, can you do it faster?" So I sped it up and went, "D'oh!" Back then we were sort of discovering these characters, and when something good popped up, Matt tried to put it in again to define the characters a little more. It's always been written as "annoyed grunt." To this day, it's never written in the script as "D'oh!" Now it's so well known that it's in the Oxford English Dictionary. Nobody called to ask me for a definition, though.

Dan Castellaneta, the voice of Homer Simpson

It started with the Simpsons shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show. Matt Groening directed those early sessions, and when I saw "annoyed grunt" in the script, I asked him, "What is that?" And he said, "Whatever you want it to be." Usually Matt has a very specific idea about how something should be read, but in that case he left it open. I remembered as a kid watching Laurel and Hardy movies, and there was a comedian by the name of Jim Finlayson who was their nemesis. Whenever Laurel and Hardy would frustrate him, he would go, "Doooh." And so I went, "Doooh." But because these pieces were only seconds long, Matt said, "Well, can you do it faster?" So I sped it up and went, "D'oh!" Back then we were sort of discovering these characters, and when something good popped up, Matt tried to put it in again to define the characters a little more. It's always been written as "annoyed grunt." To this day, it's never written in the script as "D'oh!" Now it's so well known that it's in the Oxford English Dictionary. Nobody called to ask me for a definition, though.

Paul Morigi/WireImage.com

My First Splurge

Serena Williams, tennis champion

I'll never forget: I was staying at the Essex House hotel in New York City for the U.S. Open. My sisters and I were walking along Lexington Avenue, and I said, "Oh, look at the doggy store! I want a dog." I decided on Jackie the Jack Russell because she was $1,800—less expensive than the cocker spaniel. (Now she has a diamond collar that cost more than she did.) I won the Open that year for the first time. I don't know which was a better souvenir, the title or Jackie. She completes me. It's pathetic. I hope someone else will do that soon, but for now, my little Jackie is the one.

Serena Williams, tennis champion

I'll never forget: I was staying at the Essex House hotel in New York City for the U.S. Open. My sisters and I were walking along Lexington Avenue, and I said, "Oh, look at the doggy store! I want a dog." I decided on Jackie the Jack Russell because she was $1,800—less expensive than the cocker spaniel. (Now she has a diamond collar that cost more than she did.) I won the Open that year for the first time. I don't know which was a better souvenir, the title or Jackie. She completes me. It's pathetic. I hope someone else will do that soon, but for now, my little Jackie is the one.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First Brazilian Wax

Valerie Monroe, O beauty director

Yikes! Having only ever had the gentlest (or at least the most pleasurably ungentle) treatment between my legs, I was left breathless by the ripping-out-hair-by-the-root that is exotically known as the Brazilian bikini wax. The woman who performed the procedure was amiable in a no-nonsense kind of way and was determined to accomplish her goal with a minimum of palaver (and screaming). As I lay in my paper G-string on a paper-covered table, she manipulated my legs so that she had full access to spread a thin layer of very warm wax in inch-wide strips, one after another, in my pubic area, cover each one with a piece of cloth, and, after a quick countdown (one! two! three!), yank it off.

"Miss, are you okay?" she asked after each assault, her formality a weird contrast to her proximity to my private parts. What could I say? I was as well as I could be, considering. When she was finished, I gazed down at my newly nude, pink, smarting self. I hadn't appeared as vulnerable or exposed since I was 2. Back out on the street, in my jeans and sneakers and oxford cloth button-down, I felt as if I carried a naughty little secret in my pocket: I had just seen details I'd hardly remembered, and couldn't wait to share them.

Valerie Monroe, O beauty director

Yikes! Having only ever had the gentlest (or at least the most pleasurably ungentle) treatment between my legs, I was left breathless by the ripping-out-hair-by-the-root that is exotically known as the Brazilian bikini wax. The woman who performed the procedure was amiable in a no-nonsense kind of way and was determined to accomplish her goal with a minimum of palaver (and screaming). As I lay in my paper G-string on a paper-covered table, she manipulated my legs so that she had full access to spread a thin layer of very warm wax in inch-wide strips, one after another, in my pubic area, cover each one with a piece of cloth, and, after a quick countdown (one! two! three!), yank it off.

"Miss, are you okay?" she asked after each assault, her formality a weird contrast to her proximity to my private parts. What could I say? I was as well as I could be, considering. When she was finished, I gazed down at my newly nude, pink, smarting self. I hadn't appeared as vulnerable or exposed since I was 2. Back out on the street, in my jeans and sneakers and oxford cloth button-down, I felt as if I carried a naughty little secret in my pocket: I had just seen details I'd hardly remembered, and couldn't wait to share them.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First 11 Pounds of Cheesecake (in 9 Minutes)

Sonya Thomas, 105-lb. competitive eater; world record holder in cheesecake, deep-fried okra, hard-boiled eggs, fruitcake, and 17 other foods

With cheesecake you don't need to practice—you just swallow. It goes down smooth. It's not like hot dogs. A hot dog, you have to chew. You have to use your teeth.

The competition where I set the record was the first time I'd ever eaten more than a forkful of cheesecake. People said it was good with coffee, so I washed it down with four 16-ounce cups with cream and Equal. They gave us small forks, but that was too slow, so I started using my hands. You cannot eat cheesecake fast with your hands, though; it's too messy. I thought, "Oh God, no. I've got to change my technique." Then they gave me a big spoon, and I switched to scooping, which was better.

Enjoying the cheesecake is when you eat about four to six pounds. It's gooood. Then later you're not enjoying it. The next day was not so good.

Sonya Thomas, 105-lb. competitive eater; world record holder in cheesecake, deep-fried okra, hard-boiled eggs, fruitcake, and 17 other foods

With cheesecake you don't need to practice—you just swallow. It goes down smooth. It's not like hot dogs. A hot dog, you have to chew. You have to use your teeth.

The competition where I set the record was the first time I'd ever eaten more than a forkful of cheesecake. People said it was good with coffee, so I washed it down with four 16-ounce cups with cream and Equal. They gave us small forks, but that was too slow, so I started using my hands. You cannot eat cheesecake fast with your hands, though; it's too messy. I thought, "Oh God, no. I've got to change my technique." Then they gave me a big spoon, and I switched to scooping, which was better.

Enjoying the cheesecake is when you eat about four to six pounds. It's gooood. Then later you're not enjoying it. The next day was not so good.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First Casualty

General Peter Pace, United States Marine Corps, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

I was 22, a rifle platoon leader in Vietnam. It was a great platoon, great guys. Chubby Hale, Whitey Travers, Little Joe Arnold—everybody had a nickname except Guido Farinaro. Having Guido for a name was good enough.

I was lucky: In my first six months, we had folks wounded but not killed. It was a blessing to make it that far without losing anyone. But one day, 35 or 40 of us were walking through rice paddies and small villages, patrolling. There was an exchange of fire, and Guido Farinaro was shot by a sniper.

He was the first marine I lost. We were waiting for the medevac chopper to come in and pick him up, and he died while we were waiting. I had rage inside me. We did a sweep through the village, trying to find who shot him, but we saw only women and children.

Guido had a great smile and a great sense of humor. He was born in Italy and came to the United States. He lived in Bethpage, New York, out on Long Island, and went to Chaminade High School. Most, if not all, of his classmates had gone on to college, but he determined that he was going to serve his country—his adopted country—first.

After he was killed, I wrote to his family, but I didn't try to contact them further. I figured if they wanted to be in touch with me, they would. I didn't want to impose myself on their grief. Then about two years ago, I found out that Guido's parents had died but that he had a sister out west. I wrote to her, but the letter came back, and the phones had been disconnected. I just thought that if there was anything she wanted to know about her brother and what a great marine he was, I would have been happy to share it with her.

I keep his picture on my desk at the Pentagon, to remind me of the cost of war. But I don't need the picture to see Guido's face. You don't forget. I decided that I would stay in the Marine Corps as long as I could, as long as I was adding value, because I felt I owed more than I could ever repay to Guido and the other young men who followed their second lieutenant into combat and died doing so.

General Peter Pace, United States Marine Corps, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

I was 22, a rifle platoon leader in Vietnam. It was a great platoon, great guys. Chubby Hale, Whitey Travers, Little Joe Arnold—everybody had a nickname except Guido Farinaro. Having Guido for a name was good enough.

I was lucky: In my first six months, we had folks wounded but not killed. It was a blessing to make it that far without losing anyone. But one day, 35 or 40 of us were walking through rice paddies and small villages, patrolling. There was an exchange of fire, and Guido Farinaro was shot by a sniper.

He was the first marine I lost. We were waiting for the medevac chopper to come in and pick him up, and he died while we were waiting. I had rage inside me. We did a sweep through the village, trying to find who shot him, but we saw only women and children.

Guido had a great smile and a great sense of humor. He was born in Italy and came to the United States. He lived in Bethpage, New York, out on Long Island, and went to Chaminade High School. Most, if not all, of his classmates had gone on to college, but he determined that he was going to serve his country—his adopted country—first.

After he was killed, I wrote to his family, but I didn't try to contact them further. I figured if they wanted to be in touch with me, they would. I didn't want to impose myself on their grief. Then about two years ago, I found out that Guido's parents had died but that he had a sister out west. I wrote to her, but the letter came back, and the phones had been disconnected. I just thought that if there was anything she wanted to know about her brother and what a great marine he was, I would have been happy to share it with her.

I keep his picture on my desk at the Pentagon, to remind me of the cost of war. But I don't need the picture to see Guido's face. You don't forget. I decided that I would stay in the Marine Corps as long as I could, as long as I was adding value, because I felt I owed more than I could ever repay to Guido and the other young men who followed their second lieutenant into combat and died doing so.

Photo: Barry King/WireImage.com

My First Scare

Robert Englund, director of the horror comedy Killer Pad; actor who played the character of Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street

As a child, I was obsessed with movies. I would get dropped off at this wonderful old theater in Laguna Beach, California, that had murals of pirate ships and Spanish conquistadores done in an ornate rococo style. They had a children's matinee—cartoons followed by children's programming—but on occasion the programming changed to adult fare earlier than it should have. This is how I ended up seeing The Bad Seed, that old warhorse of a play that was made into a movie, with the incredible child actress Patty McCormack as a perfect little girl who's a killer. It opens with her pounding on the hands of a child at summer camp as he holds on to the end of a pier—her tap-dancing shoes leave a crescent-shaped wound on his hands. She's doing this because he won the penmanship award that she wanted. My buddies and I, little white-bread jocks with our flattop haircuts and high-top Keds, were terrified. And I developed a real fear of braids on girls, because she wore braids. Unfortunately, I was a child of the fifties, so every girl wore her hair like that. I had to sit behind one in school—with that really severe part in the back. It gave me the creeps. I don't like that Heidi look. I know it's a sexual fantasy for some men, but it just doesn't work for me. Feel free to mock me, but I see braids and want to zip it up and run. Years later, in a subliminal way, even Princess Leia freaked me out. I'm sure Freud would have something to say about that.

Robert Englund, director of the horror comedy Killer Pad; actor who played the character of Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street

As a child, I was obsessed with movies. I would get dropped off at this wonderful old theater in Laguna Beach, California, that had murals of pirate ships and Spanish conquistadores done in an ornate rococo style. They had a children's matinee—cartoons followed by children's programming—but on occasion the programming changed to adult fare earlier than it should have. This is how I ended up seeing The Bad Seed, that old warhorse of a play that was made into a movie, with the incredible child actress Patty McCormack as a perfect little girl who's a killer. It opens with her pounding on the hands of a child at summer camp as he holds on to the end of a pier—her tap-dancing shoes leave a crescent-shaped wound on his hands. She's doing this because he won the penmanship award that she wanted. My buddies and I, little white-bread jocks with our flattop haircuts and high-top Keds, were terrified. And I developed a real fear of braids on girls, because she wore braids. Unfortunately, I was a child of the fifties, so every girl wore her hair like that. I had to sit behind one in school—with that really severe part in the back. It gave me the creeps. I don't like that Heidi look. I know it's a sexual fantasy for some men, but it just doesn't work for me. Feel free to mock me, but I see braids and want to zip it up and run. Years later, in a subliminal way, even Princess Leia freaked me out. I'm sure Freud would have something to say about that.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First International Incident

Holly Yeager, Washington, D.C.–based journalist

I was 30, working as the Pentagon reporter for a national newspaper chain. Press breakfasts were part of the routine—lots of men and lots of cholesterol around a table in a nondescript hotel meeting room. One morning I listened as the commander of all U.S. forces in the Pacific, Admiral Richard Macke, tried to do damage control after three American servicemen were charged with abducting and raping a 12-year-old girl in a rental car near their base in Okinawa, Japan. At the end of the session, Macke said quietly: "For the price they paid to rent the car, they could have had a girl." I thought my eyes would pop out of my head. Was he really saying they should have paid a prostitute instead? I looked at the others in the room for some reaction. Nothing.

Walking to my office, I kept going over that remark. By the time my story hit the wires, a few other reporters had filed stories, too. But I was a little nervous: None of them mentioned Macke's comment, whereas I had made it my lead.

My story got noticed, senators started complaining, other media outlets picked it up, and that evening the top Pentagon spokesman called me at home to say, "The defense secretary wants you to know he has accepted Admiral Macke's early retirement."

I was stunned. And then more nervous. The next day there were protests in Okinawa. The U.S. ambassador was dispatched to apologize to Japanese officials.

In Washington some of my colleagues questioned my role, as though I must have had an agenda. Had I seized on that sentence because I was the only woman reporter in the room? Would I have given it a second thought if I had been in the military—as some of them had? Was my story proof, as a few of the old-timers seemed to be suggesting, that someone like me shouldn't be doing this job?

What Macke said should have been news to any ears. But I didn't get angry. I just grew more certain that I should never hesitate to tell a story as I see it. Doing that may rock the boat, but sometimes the boat needs rocking.

Holly Yeager, Washington, D.C.–based journalist

I was 30, working as the Pentagon reporter for a national newspaper chain. Press breakfasts were part of the routine—lots of men and lots of cholesterol around a table in a nondescript hotel meeting room. One morning I listened as the commander of all U.S. forces in the Pacific, Admiral Richard Macke, tried to do damage control after three American servicemen were charged with abducting and raping a 12-year-old girl in a rental car near their base in Okinawa, Japan. At the end of the session, Macke said quietly: "For the price they paid to rent the car, they could have had a girl." I thought my eyes would pop out of my head. Was he really saying they should have paid a prostitute instead? I looked at the others in the room for some reaction. Nothing.

Walking to my office, I kept going over that remark. By the time my story hit the wires, a few other reporters had filed stories, too. But I was a little nervous: None of them mentioned Macke's comment, whereas I had made it my lead.

My story got noticed, senators started complaining, other media outlets picked it up, and that evening the top Pentagon spokesman called me at home to say, "The defense secretary wants you to know he has accepted Admiral Macke's early retirement."

I was stunned. And then more nervous. The next day there were protests in Okinawa. The U.S. ambassador was dispatched to apologize to Japanese officials.

In Washington some of my colleagues questioned my role, as though I must have had an agenda. Had I seized on that sentence because I was the only woman reporter in the room? Would I have given it a second thought if I had been in the military—as some of them had? Was my story proof, as a few of the old-timers seemed to be suggesting, that someone like me shouldn't be doing this job?

What Macke said should have been news to any ears. But I didn't get angry. I just grew more certain that I should never hesitate to tell a story as I see it. Doing that may rock the boat, but sometimes the boat needs rocking.

Photo: Derek Shapton/Random House

My First Day at School

Claire Messud, author of The Emperor's Children

We moved around alot when I was a kid, and I'd been new at school a bunch of times—in Canada, in Australia, in Canada again. But in 1980, it felt harder: We were moving to yet another new country—the United States—and this time my new school was a boarding school outside Boston, hours from home and worlds away from the Toronto public school I was leaving behind. Worst of all, I was 13.

Nineteen eighty was the year of preppy mania. The Official Preppy Handbook was a best-seller. Seventeen magazine ran a cover story highlighting preppy fashion. My parents, indulgent of my adolescent anxiety—negotiating bad skin, breasts, and boys seemed hard enough, without a whole new society of scary, well-heeled Americans to decode—had allowed me new items for my wardrobe. I was used to making my own clothes on my ancient Singer portable, out of Vogue patterns and cheap fabrics, but I knew they wouldn't be right for my new life. So I'd spent weeks planning my first-impression outfit, and when I climbed out of the taxi that late summer morning, I wore a green woolen kilt, knee-high argyle socks, Bass Weejun loafers, and a pale gray button-down shirt, with a Fair Isle sweater draped strategically over my shoulders.

Of course I'd got it all wrong. It was 85 degrees in the shade. Even before I walked into the large white clapboard dormitory, I was sweating like a pig. Perspiration poured down my temples, down my back, in the crooks of my knees. Worth it, I thought, if it meant that my Canadian bumpkinness didn't show and I could slip into the crowd like someone who was, if not born to boarding school, at least plausibly American.

But inside I grasped at once that my trouble went beyond the damp patches on my clothes. Girls—so many blonde girls—milled about, chattering as if they'd always known one another, all of them wearing Indian-print T-shirts, floaty tiered skirts, and flip-flops. My new roommate, a six-foot myopic blonde, too cool to wear her glasses, apparently couldn't even see me when I said hello. Worse than wrong, I was invisible. Even the other new kids ignored me. Only one girl, a kind black girl from St. Louis, asked where I was from and whether I didn't want to change into something less stifling. The shame of it lives in my memory as only shame can, as if it were yesterday.

Still in my kilt but without the socks and sweater, I stuck to the kind girl like a pet and trotted along mutely beside her to the opening-day events. She didn't shun me, but she laughed at me, which actually made me feel better. A few weeks later, I would buy several 1960s psychedelic print shift dresses at a garage sale for 5 cents apiece, and stuff my preppy clothes in the back of my closet. It would all, eventually, be more than okay. But I've never forgotten the early shock of it, and the pain, imperfectly repressed, remains a useful lesson in misery, a reminder of how lonely and foreign it feels when you don't belong.

Claire Messud, author of The Emperor's Children

We moved around alot when I was a kid, and I'd been new at school a bunch of times—in Canada, in Australia, in Canada again. But in 1980, it felt harder: We were moving to yet another new country—the United States—and this time my new school was a boarding school outside Boston, hours from home and worlds away from the Toronto public school I was leaving behind. Worst of all, I was 13.

Nineteen eighty was the year of preppy mania. The Official Preppy Handbook was a best-seller. Seventeen magazine ran a cover story highlighting preppy fashion. My parents, indulgent of my adolescent anxiety—negotiating bad skin, breasts, and boys seemed hard enough, without a whole new society of scary, well-heeled Americans to decode—had allowed me new items for my wardrobe. I was used to making my own clothes on my ancient Singer portable, out of Vogue patterns and cheap fabrics, but I knew they wouldn't be right for my new life. So I'd spent weeks planning my first-impression outfit, and when I climbed out of the taxi that late summer morning, I wore a green woolen kilt, knee-high argyle socks, Bass Weejun loafers, and a pale gray button-down shirt, with a Fair Isle sweater draped strategically over my shoulders.

Of course I'd got it all wrong. It was 85 degrees in the shade. Even before I walked into the large white clapboard dormitory, I was sweating like a pig. Perspiration poured down my temples, down my back, in the crooks of my knees. Worth it, I thought, if it meant that my Canadian bumpkinness didn't show and I could slip into the crowd like someone who was, if not born to boarding school, at least plausibly American.

But inside I grasped at once that my trouble went beyond the damp patches on my clothes. Girls—so many blonde girls—milled about, chattering as if they'd always known one another, all of them wearing Indian-print T-shirts, floaty tiered skirts, and flip-flops. My new roommate, a six-foot myopic blonde, too cool to wear her glasses, apparently couldn't even see me when I said hello. Worse than wrong, I was invisible. Even the other new kids ignored me. Only one girl, a kind black girl from St. Louis, asked where I was from and whether I didn't want to change into something less stifling. The shame of it lives in my memory as only shame can, as if it were yesterday.

Still in my kilt but without the socks and sweater, I stuck to the kind girl like a pet and trotted along mutely beside her to the opening-day events. She didn't shun me, but she laughed at me, which actually made me feel better. A few weeks later, I would buy several 1960s psychedelic print shift dresses at a garage sale for 5 cents apiece, and stuff my preppy clothes in the back of my closet. It would all, eventually, be more than okay. But I've never forgotten the early shock of it, and the pain, imperfectly repressed, remains a useful lesson in misery, a reminder of how lonely and foreign it feels when you don't belong.

Photo: © 2008 Jupiterimages Corporation

My First Sounds

Ellen Roth, deaf for 41 years, recipient of cochlear implants at age 43

I grew up in New York City, and on September 11 I was living with my sister about five blocks from the World Trade Center. We saw the towers get hit, we saw people jumping, we saw people covered with all that white ash. And everywhere we went, everyone was talking, and I couldn't hear their reactions, and that made me so angry. No one wanted to make the effort to talk to me because there was too much going on. My sister felt part of things, though. I didn't like that.

One day she said, "Why don't you get a cochlear implant?" I thought she was teasing, but she wasn't. Time went on, and I continued to think about it. And a year after 9/11, I got the implants.

Being able to hear was very odd at first. Everything sounded like computers, or robots, and I thought there must have been some mistake. For a year, my audiologist made adjustments. It was like I was a baby. I was hearing everything, but it made no sense. I had to learn what speech sounded like.

The first time I heard music, I cried. All my life, hearing people had told me they couldn't live without music. So I went to Tower Records, put on a pair of headphones, and listened to the Red Hot Chili Peppers. It was pretty awesome. I just listened again and again. Then hip-hop, electronica, jazz, classical, rock 'n' roll, country! I spent four hours there. I didn't want to leave.

I had a dog, a certified hearing dog. When someone came to the door or called my name, he would alert me. His name was Hurray. At the age of 13, he became deaf himself. He was a toy poodle, about ten pounds, very portable. He was my dog for 171/2 years, and he passed away two years ago. Anyway, after the implants, I heard Hurray for the first time. It turned out he had three different barks: one when I got home, when he was excited; the second when he had to go to the bathroom; the third when I was leaving—he was depressed! He didn't want me to leave!

I discovered that he snored when he slept on my lap.

Before the implants, when I walked Hurray, I would of course see people. Now I could hear them say "Good morning." I thought, "Oh, they talk to me!" And I realized that was probably why people used to be so stone-faced with me—they must have thought I was ignoring them. Now it's so precious to be able to connect.

On the other hand, the big thing I realized is that people talk too much! All day long, they talk about nothing!

Little things surprised me, too. A person breathing hard makes a sound. In my apartment, I can hear the woman upstairs walking around. When I cook, I can hear the sauce bubbling, the toaster popping up. And I've stopped slurping soup. I have deaf friends, and I can hear the sounds they make when they eat; it's like, "Okay, guys, you're making some noise here...."

Not long after getting the implants, while driving my car, I heard this eeeee sound. It cost me $30 to have the brake pads changed. I told the mechanic, "You know, I had to pay a lot more before." And he said, "You destroyed your rotors, that's why." I guess deaf people lose out a lot on that brake-pad warranty.

At the time I got the implants, I also went back to school. For ten years, I'd been a vocational rehabilitation administrator. Now I'm a rabbinical student and a senior vice president at a company that produces videos using American Sign Language. I want to become a Kabbalah counselor. I want to understand everything.

Ellen Roth, deaf for 41 years, recipient of cochlear implants at age 43

I grew up in New York City, and on September 11 I was living with my sister about five blocks from the World Trade Center. We saw the towers get hit, we saw people jumping, we saw people covered with all that white ash. And everywhere we went, everyone was talking, and I couldn't hear their reactions, and that made me so angry. No one wanted to make the effort to talk to me because there was too much going on. My sister felt part of things, though. I didn't like that.

One day she said, "Why don't you get a cochlear implant?" I thought she was teasing, but she wasn't. Time went on, and I continued to think about it. And a year after 9/11, I got the implants.

Being able to hear was very odd at first. Everything sounded like computers, or robots, and I thought there must have been some mistake. For a year, my audiologist made adjustments. It was like I was a baby. I was hearing everything, but it made no sense. I had to learn what speech sounded like.

The first time I heard music, I cried. All my life, hearing people had told me they couldn't live without music. So I went to Tower Records, put on a pair of headphones, and listened to the Red Hot Chili Peppers. It was pretty awesome. I just listened again and again. Then hip-hop, electronica, jazz, classical, rock 'n' roll, country! I spent four hours there. I didn't want to leave.

I had a dog, a certified hearing dog. When someone came to the door or called my name, he would alert me. His name was Hurray. At the age of 13, he became deaf himself. He was a toy poodle, about ten pounds, very portable. He was my dog for 171/2 years, and he passed away two years ago. Anyway, after the implants, I heard Hurray for the first time. It turned out he had three different barks: one when I got home, when he was excited; the second when he had to go to the bathroom; the third when I was leaving—he was depressed! He didn't want me to leave!

I discovered that he snored when he slept on my lap.

Before the implants, when I walked Hurray, I would of course see people. Now I could hear them say "Good morning." I thought, "Oh, they talk to me!" And I realized that was probably why people used to be so stone-faced with me—they must have thought I was ignoring them. Now it's so precious to be able to connect.

On the other hand, the big thing I realized is that people talk too much! All day long, they talk about nothing!

Little things surprised me, too. A person breathing hard makes a sound. In my apartment, I can hear the woman upstairs walking around. When I cook, I can hear the sauce bubbling, the toaster popping up. And I've stopped slurping soup. I have deaf friends, and I can hear the sounds they make when they eat; it's like, "Okay, guys, you're making some noise here...."

Not long after getting the implants, while driving my car, I heard this eeeee sound. It cost me $30 to have the brake pads changed. I told the mechanic, "You know, I had to pay a lot more before." And he said, "You destroyed your rotors, that's why." I guess deaf people lose out a lot on that brake-pad warranty.

At the time I got the implants, I also went back to school. For ten years, I'd been a vocational rehabilitation administrator. Now I'm a rabbinical student and a senior vice president at a company that produces videos using American Sign Language. I want to become a Kabbalah counselor. I want to understand everything.