Is Cory Booker the Greatest Mayor in America?

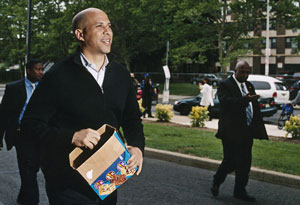

Booker bringing snacks to polling place volunteers.

PAGE 3

Booker asks his folks, who are visiting for a few weeks, to meet him on up-and-coming Halsey Street for a little shopping. Well, not shopping per se—Booker is resolutely not a "stuff" guy; he's content with his old-school BlackBerry and simply doesn't get the whole iPad frenzy—but there are saplings in the form of new businesses that he needs to check on. He'll show some money-love to the Coffee Cave, which got its start through the city's small business loan program and now sells upscale java and baked goods befitting Bay Area hipsters, and a salon called Cut Creators, where he wants to treat his dad to a trim. (Booker had been at the salon just yesterday for the grand opening of its second location, but as he explains, "It's one thing to cut a ribbon; it's another to patronize the place.") While splashier achievements like the building of a Marriott—the first new hotel to open downtown in 38 years—and a deal to break ground on the tallest tower in the city have incalculable significance, the colonization of scarred streets with edgy shops and stylish boîtes is just as key, supplying the sort of cultural flavor that can make a city a sexy destination. In progress: a $120 million plan to create a "Teachers Village," with charter schools as well as housing and retail that will be marketed to educators from nearby colleges like Rutgers and Seton Hall, giving them some incentive to live where they work.

Carolyn and Cary Booker are semiregulars in Newark, whether campaigning for their son, attending his speeches, offering counsel, or keeping the pressure on to find a wife. As two of the first black executives at IBM in the 1960s, they were pioneers who never particularly felt like pioneers, as their focus was always on their boys, Cory and his older brother, Cary (cofounder of a company that runs charter schools in Memphis). They instilled in both a ferocious work ethic, and gave them the psychic wherewithal to move gracefully through the almost all-white world of Harrington Park, New Jersey, where the kids grew up. Today Carolyn, in a magenta sweater set, is flipping through a magazine at Michael Lamont Neckwear while her dapper husband with the North Carolina drawl tries out various shirt-and-tie combos. The store is sleek, with exposed brick and blond wood floors—a big step up from the cardboard box out of which Michael Lamont used to sell his wares. "You know what I like about this guy?" Booker says of Lamont, who is standing by in a red-and-white-striped shirt and red suspenders. "Newark artist"—he gestures to a picture of the great Negro Leagues pitcher Satchel Paige on the wall by the local painter Serron; "Newark jazz station"—the excellent WBGO is drifting through the speakers; "Newark business"—Booker flips over a necktie and points out the Newark label stitched into the back. It's the lens through which Booker sees everything: Is it good for Newark? Where does Newark fit in? What about Newark?

Back in the SUV, with a detective at the wheel, Booker tears into a takeout container of scrambled egg whites with peppers and onions. He's been a vegetarian since Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar. As Booker describes it in his soothing, storyteller's tenor, "I decided to take to heart Socrates' admonishment about the unexamined life"—the one that says such a life isn't worth living. "And I started reading everything I could. And the more I read, from the environmental impact of eating meat to the health issues to Gandhi, the more I realized that eating the extreme amounts that I really enjoyed was not resonant with my spirit, with my values. So I tried to go cold turkey, and my body just took off—I felt so good. I'm not one of those judgmental vegetarians who says everybody should do this, but for me it works, and it works very well."

In a city not known for its salad bars, Booker is an anomaly, and his diet is only part of it. He has no known vices or addictions (except books—a friend once joked that Booker's crack den was Barnes and Noble); drink and drugs have never held any allure. During high school, friends would offer him money just to see him take a sip of beer. In mission and temperament, Booker is the quintessential designated driver. "TV, food, alcohol, sex—they're all things we can fill our lives with that can distract us from our purpose," he says.

"I was one of those kids who wanted to be a good kid," he notes, back in his office now—a circular City of Newark seal on the wall behind his head creating an unintentional halo effect. "There could be a lot of theories on this. My brother and I were the only black kids in the neighborhood, and I really did not want to fit into the stereotypes that people were putting in my face. And I grew up with these parents that were so righteous. My dad is like jazz; he's the jokester. But my mom is a gospel hymnal. She is definitely regal. Honor was so important to them, and I really found myself in high school being the guy who was always there for people, comforting someone who is going through a breakup, holding somebody's hair while they're puking. I really liked being an older brother figure within a group of friends, and I had friends in every group: the jocks, the band kids, the geeks. It felt like I could move seamlessly."

Next: Turning down Obama

Carolyn and Cary Booker are semiregulars in Newark, whether campaigning for their son, attending his speeches, offering counsel, or keeping the pressure on to find a wife. As two of the first black executives at IBM in the 1960s, they were pioneers who never particularly felt like pioneers, as their focus was always on their boys, Cory and his older brother, Cary (cofounder of a company that runs charter schools in Memphis). They instilled in both a ferocious work ethic, and gave them the psychic wherewithal to move gracefully through the almost all-white world of Harrington Park, New Jersey, where the kids grew up. Today Carolyn, in a magenta sweater set, is flipping through a magazine at Michael Lamont Neckwear while her dapper husband with the North Carolina drawl tries out various shirt-and-tie combos. The store is sleek, with exposed brick and blond wood floors—a big step up from the cardboard box out of which Michael Lamont used to sell his wares. "You know what I like about this guy?" Booker says of Lamont, who is standing by in a red-and-white-striped shirt and red suspenders. "Newark artist"—he gestures to a picture of the great Negro Leagues pitcher Satchel Paige on the wall by the local painter Serron; "Newark jazz station"—the excellent WBGO is drifting through the speakers; "Newark business"—Booker flips over a necktie and points out the Newark label stitched into the back. It's the lens through which Booker sees everything: Is it good for Newark? Where does Newark fit in? What about Newark?

Back in the SUV, with a detective at the wheel, Booker tears into a takeout container of scrambled egg whites with peppers and onions. He's been a vegetarian since Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar. As Booker describes it in his soothing, storyteller's tenor, "I decided to take to heart Socrates' admonishment about the unexamined life"—the one that says such a life isn't worth living. "And I started reading everything I could. And the more I read, from the environmental impact of eating meat to the health issues to Gandhi, the more I realized that eating the extreme amounts that I really enjoyed was not resonant with my spirit, with my values. So I tried to go cold turkey, and my body just took off—I felt so good. I'm not one of those judgmental vegetarians who says everybody should do this, but for me it works, and it works very well."

In a city not known for its salad bars, Booker is an anomaly, and his diet is only part of it. He has no known vices or addictions (except books—a friend once joked that Booker's crack den was Barnes and Noble); drink and drugs have never held any allure. During high school, friends would offer him money just to see him take a sip of beer. In mission and temperament, Booker is the quintessential designated driver. "TV, food, alcohol, sex—they're all things we can fill our lives with that can distract us from our purpose," he says.

"I was one of those kids who wanted to be a good kid," he notes, back in his office now—a circular City of Newark seal on the wall behind his head creating an unintentional halo effect. "There could be a lot of theories on this. My brother and I were the only black kids in the neighborhood, and I really did not want to fit into the stereotypes that people were putting in my face. And I grew up with these parents that were so righteous. My dad is like jazz; he's the jokester. But my mom is a gospel hymnal. She is definitely regal. Honor was so important to them, and I really found myself in high school being the guy who was always there for people, comforting someone who is going through a breakup, holding somebody's hair while they're puking. I really liked being an older brother figure within a group of friends, and I had friends in every group: the jocks, the band kids, the geeks. It felt like I could move seamlessly."

Next: Turning down Obama

Photo: Brian Finke