The Power of the Pin

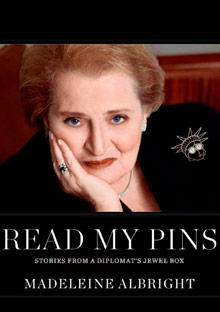

There are power suits, power heels—but a power pin? Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright explains how she used brooches to say everything from "I come in peace" to "Don't tread on me" in Read My Pins.

When we think about international diplomacy, we usually envision high-level meetings with handshakes and important documents to be signed. My predecessors as secretary of state appeared at such meetings in their fancy suits with power ties; when I took office, I thought the time might be right to display pins with attitude.The idea of using pins as a diplomatic tool can't be found in any State Department manual; in fact, it would never have happened if not for Saddam Hussein. After I criticized Hussein for failing to cooperate with U.N. weapons inspectors, the government-controlled Iraqi press referred to me as an "unparalleled serpent."

By chance, I had a meeting scheduled with Iraqi officials; I decided to wear a pin showing a reptile coiled around a branch. When the meeting was over, a reporter asked me why I had chosen that particular pin. I smiled and said "Just my way of sending a message." Before long, jewelry had become part of my personal diplomatic arsenal. The first President Bush had been known for saying "Read my lips." I began urging colleagues to "Read my pins."

See some of the pins in her collection

As an instrument of foreign policy, a pin is clearly not in the same league as a peace agreement or a deal to limit nuclear arms. So I do not claim too much, but I do think that the right symbol at the correct time can add something meaningful to a relationship, whether that something is warm and fuzzy—or very, very sharp.

It was also enjoyable to see how other foreign ministers would react. If I had on a ladybug or a butterfly, they knew that I was in a good mood. If I wore my angel pin, they could expect me to be gentle. But if it was a spider or a wasp, they had fair warning to watch out.

During four years of Middle East peace negotiations, I almost exhausted my collection. When first speaking on the subject, I wore a dove pin that had been a gift from the widow of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who had been assassinated because of his support for peace. Later, in Jerusalem, Mrs. Rabin presented me with a whole necklace of doves, saying that the dove pin might need reinforcements.

She was right.

In the months that followed, I wore my balloon pin to symbolize high hopes for peace; then my lion to encourage bravery. As the negotiations dragged, I wore a turtle to suggest more speed, then a snail to highlight my impatience and finally—when the grumpy old men on both sides failed to reach an agreement—a crab. Today, if I had to choose a pin to wear in the Middle East, I would return to the dove—because the stakes are too high for peacemakers to give up.

Deciding what pin to wear to a particular meeting was great fun, but also more complicated when I was preparing to go on a trip. Usually I did not have a lot of time, so I often just grabbed a handful of pieces from my dresser drawer and hoped for the best. Of course, one problem with pins is that they can do a lot of damage to your wardrobe. After awhile, I found that I had to wear larger (and crazier) pins just to cover up the holes.

There was also the question of the clasp—which has a long history. As I write in my new book, ancient hunter-gatherers used pieces of flint to keep their clothes on while running around the forest in pursuit of their next meal. Royal burial sites in Ur, the home city of the patriarch Abraham, included gold and silver pins that would have been used to secure robes at the shoulder. I mention these origins only to show that I could not possibly have been the first person to be embarrassed by a pin that came undone at the wrong time. For me, the wrong time was the ceremony at which I was sworn in as secretary of state.

For the occasion, I had purchased an antique pin showing a gold eagle with widespread wings. What I failed to notice was that the clasp was not only old but complicated: Fastening it was a multistep process that I neglected to complete.

All went well until I had one hand on the Bible and the other in the air.

Then, I looked down and saw that my beautiful pin was dangling sideways. With all the commotion, I had no time to fix the problem until after the photographers had done their work, showing me standing next to the president with an eagle that had forgotten how to fly.

Deciding what pin to wear to a particular meeting was great fun, but also more complicated when I was preparing to go on a trip. Usually I did not have a lot of time, so I often just grabbed a handful of pieces from my dresser drawer and hoped for the best. Of course, one problem with pins is that they can do a lot of damage to your wardrobe. After awhile, I found that I had to wear larger (and crazier) pins just to cover up the holes.

There was also the question of the clasp—which has a long history. As I write in my new book, ancient hunter-gatherers used pieces of flint to keep their clothes on while running around the forest in pursuit of their next meal. Royal burial sites in Ur, the home city of the patriarch Abraham, included gold and silver pins that would have been used to secure robes at the shoulder. I mention these origins only to show that I could not possibly have been the first person to be embarrassed by a pin that came undone at the wrong time. For me, the wrong time was the ceremony at which I was sworn in as secretary of state.

For the occasion, I had purchased an antique pin showing a gold eagle with widespread wings. What I failed to notice was that the clasp was not only old but complicated: Fastening it was a multistep process that I neglected to complete.

All went well until I had one hand on the Bible and the other in the air.

Then, I looked down and saw that my beautiful pin was dangling sideways. With all the commotion, I had no time to fix the problem until after the photographers had done their work, showing me standing next to the president with an eagle that had forgotten how to fly.

In 2006, I spoke at the D-Day Museum in New Orleans, an event delayed for a year because of Hurricane Katrina. This gave me a chance to look around the city, large parts of which remained in ruins. I was saddened by the contrast between the museum—which celebrated America at its best—and the shabby treatment accorded to local residents.

At the reception following my speech, I was approached by a young man bearing a pin. "My mother loved you," he said, "and she knew that you liked pins. My father is a veteran with two purple hearts and gave her this one for their 50th wedding anniversary. She died as a result of Katrina, and would have wanted you to have it. It would be an honor to her if you would accept."

I call it the Katrina pin, a flower composed of amethysts and diamonds. I wear it as a reminder that jewelry's greatest value comes not from precious stones or brilliant designs, but from the emotions we invest. The most cherished gems are not those that dazzle the eye, but those that recall to our minds the face and spirit of a loved one.

As the pages of Read My Pins illustrate, pins are inherently expressive. I was fortunate to be secretary of state at a time that allowed me to experiment by using pins to communicate a diplomatic message. One might scoff and say that my pins didn't exactly shake the world. To that I can reply only that shaking the world is the opposite of what diplomats are placed on Earth to do.

See some of the pins in her collection

Albright talks about the secret meaning of her pins

At the reception following my speech, I was approached by a young man bearing a pin. "My mother loved you," he said, "and she knew that you liked pins. My father is a veteran with two purple hearts and gave her this one for their 50th wedding anniversary. She died as a result of Katrina, and would have wanted you to have it. It would be an honor to her if you would accept."

I call it the Katrina pin, a flower composed of amethysts and diamonds. I wear it as a reminder that jewelry's greatest value comes not from precious stones or brilliant designs, but from the emotions we invest. The most cherished gems are not those that dazzle the eye, but those that recall to our minds the face and spirit of a loved one.

As the pages of Read My Pins illustrate, pins are inherently expressive. I was fortunate to be secretary of state at a time that allowed me to experiment by using pins to communicate a diplomatic message. One might scoff and say that my pins didn't exactly shake the world. To that I can reply only that shaking the world is the opposite of what diplomats are placed on Earth to do.

See some of the pins in her collection

Albright talks about the secret meaning of her pins