Your stocks go poof! You lose your house. A bear almost kills you. The envelope you just opened contains anthrax. Four women still reeling from shock tell how they've managed to regain a sense of stability, safety, confidence, and control.

Family psychologist Pauline Boss, PhD, a professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, believes that resilience is based on being able to accept ambiguity and find hope amid uncertain conditions. Boss, the author of Loss, Trauma, and Resilience, echoes the ideas of Buddhist thinker Pema Chödrön, who advises that in adversity lies the opportunity to see clearly where we want and don't want to be. "The only time we ever know what's really going on is when the rug is pulled out and we can't find anywhere to land," Chödrön writes in her book When Things Fall Apart.

The following four women have been tested in profound ways that defy simple solutions. "I don't think there is a Hallmark sympathy card for any one of them," says Boss, who analyzes their stories. With her help in highlighting what each woman has done right to overcome difficulty, and how she might do better in areas where she's still struggling, we can all find lessons for navigating tough times.

Hit from All Sides

Hit from All SidesJanet Hanson, 56, outside the New York Stock Exchange, ponders her future.

Attacked by a Bear

Attacked by a Bear Allena Hansen, 57, at home in Caliente, California, with her dogs, Arky and Decoy, who saved her life.

Poisoned by Anthrax

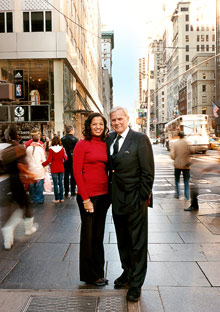

Poisoned by AnthraxCasey Chamberlain, 30, and her former boss Tom Brokaw near NBC-TV in New York City.

A Home Lost to Foreclosure

A Home Lost to ForeclosureJanelle Pereira, 24, with her husband, Scott, and son Joseph, 5, in front of the home they lost in Atwater, California.

Photo: Rob Howard

On February 12, 2007, Janet Hanson sat across from Katie Couric, being interviewed for CBS News. They were discussing the success of her company, 85 Broads, a network of 18,000 female professionals and students around the world who promote women's leadership in the workplace and beyond. A former vice president at Goldman Sachs, Janet had started the organization in 1997 for the firm's female employees and alumnae—the name, a play on its address (85 Broad Street). When she came up with the idea, she'd left Goldman to raise her first child and wanted to stay plugged into Wall Street. At that time, in 1997, she had already founded Milestone Capital—a money market fund company overseeing more than $2 billion in assets—and would stay in finance by later becoming a managing director at Lehman Brothers.

During her interview with Couric, Janet talked confidently about investing in other women. But she remembers thinking, "What did it really cost me?"

"There was this overwhelming sense of sadness and loss," she says. A few months earlier, her husband of 18 years had left her. "As the camera rolled," she says, "inside I'm dying because all I'm thinking about is him."

If that was a low point, it wasn't the first—or the last. In 2002, after being diagnosed with breast cancer, Janet underwent a bilateral mastectomy; then, to keep the cancer from spreading to her ovaries, had them removed as well, causing what doctors term traumatic menopause. Rebounding from that trauma, two years later she accepted the job at Lehman Brothers to bring in female talent—a mission perfectly in line with her goals at 85 Broads. She was paid largely in company stock. Convinced that the stock would maintain its value after it vested, she started plowing her own money, almost $5 million, into 85 Broads, expanding it into the global network it is today. By early 2007, she felt overextended and, with her marriage on the rocks, decided to trade her managing director job at Lehman for a two-year consulting contract. At her first opportunity, in February 2008, she cashed out about two thirds of her stock, but by then, due to the credit crisis, it had dropped from $82 to $48 a share. "That was not a happy thing. I was starting to be concerned about my luck," she says. "I couldn't turn my marriage around, or my health. ... There was this paralyzing dread that whatever could go wrong, would."

Then in September, the unthinkable happened: Lehman Brothers collapsed. Her stock became worthless. "I was in shock, absolute shock," she says.

Since then Janet has faced having no income. She not only fears having to shut down 85 Broads but also worries about supporting her children, Meredith, a college sophomore, and Chris, a high school senior. "I am terrified," she admits. "You really have to sit back and ask, 'Did I fail?'"

Even more acute than the evaporation of her net worth is the ongoing grief she feels about losing her husband. For more than a year after he left, she prayed he would come back, only to discover that he was commuting to another state to see an old girlfriend. "My sense of failure around my marriage is so massive, I feel like I'm engulfed in flames every single day," she says. "It's like I can't breathe, I can't get out from under the excruciating pain and loss."

Despite such abysmal moments, she does find the humor in her situation ("Jesus, you're 56 and don't have any boobs and you're kind of a mess," she says, addressing herself). She has also found a powerful source of strength: The women of 85 Broads have, it turns out, been her greatest investment, because now they are offering her priceless support, emotional and practical. Most of all, she finds passion in sharing her knowledge with young women around the country. Living for now off her savings, Janet says, "I have no intention of throwing in the towel. I will make it, come hell or high water. Walking away from 85 Broads would be a far bigger tragedy than losing my husband."

Dr. Boss' Analysis: Look for evidence of your accomplishments.

Highly successful people often come from the worldview that if you work hard and are a good, fair person, you can solve anything. And when that fails, many blame themselves, which makes things worse. It's no surprise that Janet's husband's walking out has hit her harder than her other losses. Research shows that betrayal from inside the family is one of the toughest blows to deal with because you can't readily make meaning out of it. Having someone disappear from your life, in fact, is one of the most difficult forms of "ambiguous loss"—a situation that has no real emotional closure (the husband is not dead, but he's gone from your life as you knew it). One way to start healing is to look for evidence of past competencies. (Ask other people—family, friends—to help you remember if you can't.) Janet, for instance, was able to build a network, become a CEO of her own company, and raise two children—and she's done well to reidentify with those accomplishments. She might also find it helpful to recall the strengths that have gotten her through past losses. Overall it's inspiring that she's trying to make something good come of her trials by persevering with 85 Broads and speaking to young women. The support of others is important in easing a person's pain and helping her begin to imagine new options.

Photo: Diana Koenigsberg

July, 22, 2008, was just another day for Allena Hansen. She'd gone with her two dogs to an area on her 70-acre property in the mountains outside Bakersfield, California, where she was putting in a vineyard. A single mother of one college-age son, Allena is used to doing things on her own. But this day, as she emerged from a well she was working on, she startled a black bear. In the nanosecond before either of them moved, Allena remembers thinking, "Uh-oh."

The next instant, the bear was on her. "I heard chomp, chomp, chomp," she says. "I felt it bite through my skull. I heard kind of a squishy, crunchy pop. I went, "There goes my eye." Then it got hold of my face, and I could feel it tearing off." One of the worst moments was "watching that little bugger spit my teeth out."

Though she was all of 100 pounds, Allena managed to dig her thumb into the bear's eye, causing it to loosen its grip. Right then, one of her dogs—a huge mastiff, prophetically named Decoy—lunged for the animal. "I remember thinking that if my dog was willing to offer his life to save me, the least I could do was try to live," she says.

Managing to free herself, Allena stumbled down a brush-covered trail for half a mile to her truck; Decoy had already made it there and was waiting for her. As she got in and started the ignition, she caught sight of her face in the rearview mirror. "I was surprised to see I was still wearing my white baseball cap—it was askew and bloody, but amazingly, it was still on," she says. "Then I realized that cap was my scalp." She gave herself two seconds to take in the information and then decided, "That's enough." How she drove the few miles to the mountain fire station, she doesn't know. When she climbed out of the truck, several firefighters rushed to her aid and kept her from going into shock while they called for a helicopter to take her the 123 miles to the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center emergency department.

"One of the firemen is holding me up from behind so I don't fall down and aspirate my own blood, and he's going, 'You're doing great, just hang on.' I'm like, 'No, I'm not, we both know I'm not, so just go easy on yourself, okay?' The guy was so grateful for being able to laugh," Allena says.

At UCLA, doctors operated for six hours, and though they were able to save her face and eye, Allena would never look the same. Whatever shock she felt at first seeing herself after surgery, however, was offset by her happiness to be alive. Since then Allena has considered further surgery but is wavering. "The Jim Lehrer eye bag, yes, I want that gone," she says, pointing to the gathering of skin underneath her right eye. "But the scar from the claw that shows I literally kissed a bear on his bear lips? These scars are hard-earned trophies for what I've been through; they are actually something I can be grateful for. I am proud of them. ... I can go talk to little girls and say, 'I'm still beautiful, even with these!'"

Along with self-acceptance, Allena has found compassion for her attacker. Wardens from the Department of Fish and Game intended to kill the animal but gave up when they couldn't track down the exact bear. "At the time I thought, 'If this thing would attack me with my dogs nearby, how hard would it be to snag a kid on the way to school?'" she says. "So I'm weighing the thought of "Yeah, kill it; it's a bully," with the understanding that here is this poor, terrified, young adolescent bear, a refugee from all the forest fires we've had. It found a place with berries and a place to sleep—and then this woman comes. It was probably thinking, "I tried to warn her away, but she didn't get it. Then she came into my private place and I had to bite her, and now they are chasing me." That breaks my heart. Yes, I'm pissed off at the little refugee for not trusting me, but I can't blame him."

Alone most days now with her dogs—the second one having been brought home by a neighbor—Allena has found community online by blogging on Open.Salon.com. Writing is allowing her to gain perspective, not just about this incident but about other traumas in her life—a fire that took her home, a horseback riding accident that broke her back. "When you've lost everything, and I have, eventually you get kind of...existential. You simply say, 'This is happening,' because all you have is right now. Your choice is either to accept it or let go and die. And I'm keeping on going."

Dr. Boss' Analysis: Getting to laughter means getting to hope.

Finding meaning, some rationale or coherence about what has happened, is vital for coping with trauma and loss. This is what Allena has done repeatedly—by reframing the issue of her scars, by deciding to offer young girls another definition of beauty, by shifting from a negative perspective ("the bear was a bully") to a positive one ("he's a victim too"). Contrary to "an eye for an eye" thinking, retribution is often not therapeutic, but forgiveness is, because it creates feelings of connection. Allena's humor is another good example of resiliency—once we can laugh, we begin to find hope.

Although the first tendency after trauma is often to withdraw, finding meaning comes from talking with others who are facing the same problem. Online interaction is a great first step, and sometimes it's the only practical way for people who have shared a rare experience—like surviving a bear attack—to find each other. But live, human interaction is ideal, which is another reason for Allena to pursue her desire to share her experiences with girls.

Photo: Rob Howard

Opening a letter addressed to Tom Brokaw was something Casey Chamberlain had done hundreds of times as a desk assistant at NBC Nightly News in New York. But one day, about a week after 9/11, the childlike scrawl on one envelope caught her attention. "It scared me right away because I thought this is either someone playing a horrible prank or this is someone really creepy and weird," she says. Inside was a note saying "Death to America, Death to Israel, Allah is great," and what Casey recalls as a granular substance that looked like a cross between brown sugar and sand. She threw the grains in the trash and stacked the letter with the rest of the mail to give Brokaw's assistant, Erin O'Connor.

About 10 days later, the glands in Casey's neck swelled alarmingly, and she developed black spots on her face and legs, like tiny bug bites. She went to the doctor, who thought it might be a reaction to the Accutane medication she was taking, and put her on an antibiotic. "I was very, very ill," she says. "I couldn't get out of bed; I felt like something was running through my entire body."

Erin, coincidentally, was also out sick. But it wasn't until after Robert Stevens, a photo editor for the Florida-based tabloid The Sun, died on October 5 that anyone began to make a connection between the two NBC assistants. A week later, one of Casey's bosses called her in to tell her what they'd pieced together: Stevens had inhaled anthrax from a letter sent to his company. Casey, they believed, had contracted cutaneous anthrax.

"She was a model of cool courage in the way she handled this outrageous act," Brokaw remembers. "She helped all her colleagues in the newsroom get through the ordeal with her resolute calm." But Casey didn't see herself that way. The potentially lethal effects of the toxin terrified her. Even more unnerving was "the simple fact that someone had sent this in the mail, intending to inflict harm on others," she says. Still feeling sick at that point, she was prescribed the antibiotic Cipro for 100 days. Slowly, her physical symptoms improved. The psychological ones did not.

"I definitely suffered from post-traumatic stress, and continue to," Casey says. "Throughout that entire time there were false scares, copycat attacks—I worked in that news environment, and whenever I would hear about or see those happenings anywhere, it brought it all back to me." Also, because she had taken papers from the office home the day she opened the letter, all her clothes, furniture, photos, and mementos had to be destroyed. "What was most traumatic about it was the fact that the substance was in my personal space, what is supposed to be my sanctuary, my safe place," she says. "When that horror makes its way into your home, you think, 'What if it's over there, or on that thing?' You can't relax. Spores can live more than 100 years; they don't die easily."

Casey had her apartment cleaned numerous times and eventually moved to the Boston area, where she lives now with her 2-year-old daughter and works for a construction firm. She still suffers from several health issues as a result of the attack, she says, and has seen a therapist to try to deal with the emotional fallout. But because the person who sent the letters has never been found (the FBI's prime suspect committed suicide before any final verdict could be made), the event remains ever present in her life. "On a day-to-day basis, I think about these attacks. Because we're such a small group, we are often forgotten, but we were victims of terrorism as well," says Casey. "I find it disheartening that we haven't been able to sit in a courtroom, look a potential perpetrator in the eye, and say, 'This is how you changed my life so drastically.' My sense of security—that was completely robbed from me."

What she has gained, however, is a greater appreciation for the family and friends who rallied around her, along with a new "family" of others affected by anthrax. "This is an odd thing that doesn't happen to very many people, so it's hard to explain to others," she says. "We've all had such similar experiences, we are able to bounce different feelings and ideas off each other and share thoughts. It's been really beneficial knowing the other survivors."

Dr. Boss's Analysis: Don't insist on closure.

Reaching out to other anthrax survivors is key to Casey's ability to make a life for herself after terrorism ripped away her sense of stability. Seeking therapy is a great step as well, although talking one-on-one doesn't always provide a complete solution in the case of ambiguous loss—and what is more ambiguous than losing your sense of security?

Research shows that movement therapy—walking, dancing, yoga, for example—can help link the mind to a more peaceful rhythm of the body. Also, Casey needs a sense of justice, but she's not likely to get the one she wants soon. In cases like this, if we insist on closure, we won't heal. Our only choice is to envision new options—and that's difficult because when we're highly anxious or depressed, our creativity shuts down. So the best thing to do is to surrender, sit back, listen and feel, and be aware. Talk with other people. Go to the theater, enjoy music, get out in nature—in other words, stimulate your imagination.

Photo: Diana Koenigsberg

Getting a real estate license seemed like the perfect career move for Janelle Pereira. A 19-year-old single mother who had separated from her high school sweetheart a year after marrying him, Janelle was working as a waitress and living with her parents. The year was 2003, and Merced County in California's rural San Joaquin Valley was experiencing a boom—houses were selling faster than the hotcakes at the restaurant. She figured selling homes was like waiting tables; talk to people and give them what they want. "Only the tips are bigger," she says.

After a three-week course to get her license, Janelle landed a job at Coldwell Banker. Sure enough, she went from minimum wage to making an average of $25,000 a month. "I got in and worked very, very hard," she says. "People were buying houses sight unseen."

She quickly cleared up $15,000 in credit card debt and bought a new Toyota. By 2005 she was ready to become a homeowner, purchasing a $315,000 four-bedroom contemporary on a quiet cul-de-sac, perfect for bike riding with her young son. The house was 100 percent financed with an adjustable rate mortgage, and she put $60,000 of her savings into renovations. Janelle felt she was being responsible: "I thought, 'Okay, I can remodel, get new this, new that, and the house will be worth even more, because that's what's happening today.'" Besides, she says, wasn't real estate always a solid investment?

But as 2006 wore on, the housing boom started to go bust, and Merced County ultimately gained the unfortunate distinction of having one of the highest foreclosure rates in the nation. "People stopped buying, and those who wanted to sell were having a hard time because now they had negative equity," Janelle says. "My income started to disappear." Just as that happened, payments on her mortgage—which had seemed like such a good idea when she was making $25,000 a month—ballooned from slightly under $2,000 to $3,700.

Janelle threw herself into her work, but by the end of 2006 she was going months without a paycheck. The only bright spot in her life was that she reconciled with her husband, but even with the help of his modest salary from a retail job, they struggled. "I remember sitting down one month to write the mortgage check, and it was literally all the money we had," she says. After April 2007, they could no longer pay it.

One evening the following January, Janelle came home from work to find a foreclosure notice posted on her front door. Even though she'd known it was coming, her stomach knotted, and she thought, "This is it." A month later, the bank called to inform her that she had to move.

"I loved that house," Janelle says. "It was the all-American home, a place where I thought we would stay for at least 10 years." Yet all those months leading up to the foreclosure had been so stressful that when it finally happened, Janelle did feel a bittersweet sense of relief. Her pastor had told her something too. "What you need is a home, not a house," he said—advice that really struck a chord. The Pereiras found a smaller place to rent, settled in, and had another baby.

Janelle continues to work for Coldwell Banker—ironically, with foreclosures—and today is often the person who must knock on the door to deliver the bad news. It's a job she doesn't shirk. "I really relate to the homeowners, some of whom are very sad," she says. "I usually share my story, telling them that while it's hard to relocate and start over, they will get through it." Her old house? It sold to another family for $155,000. "I can sit around and be depressed about it—which I did for a little bit—but eventually I had to move on. I don't feel ashamed. It's just a part of life. I believe I had good intentions."

Dr. Boss' Analysis: Live with paradox

We often get stuck trying to fix what can't be fixed. But resilience lies in learning to live with less-than-perfect outcomes. An exercise called "both/and thinking" helps you get there: Instead of an all-or-nothing attitude, you embrace the paradox that two states of being can be true, such as "I am both distressed about my lost hopes and dreams and confident I can find new ones." Janelle offers a couple of examples of this. One was acknowledging that she was sad about losing her house and, at the same time, relieved about no longer having to struggle every month to hang on to it. Another example was her realization that yes, she went into foreclosure, and yes, she is still a good and responsible person. Janelle also turned to her faith, which can provide insight into one's circumstances.

From the January 2009 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine.

Photos: Rob Howard; Diana Koenigsberg