What Prayer Really Means

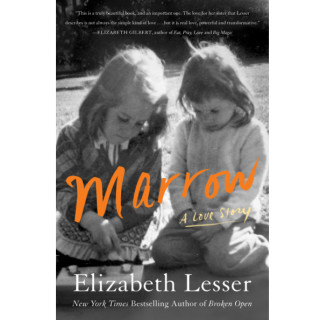

Elizabeth Lesser, the author of new memoir Marrow, talks about the many different ways to pray and why even if you don't have a strong belief in a higher power, prayer might be what you've been looking for.

Photo: Bananastock/Thinkstock

When was the last time you let go of the notion that you're in control of your life and prayed? Even if you only have the slightest sense that a higher power is at work in the world, that little leap of faith just might give you the perspective you've been searching for.

I grew up in an atheist family. While my parents were raised in religious homes—my father in a kosher Jewish house, my mother in a devout Christian Science one—as adults they renounced their adherence to organized religion. They raised their daughters in a religion-free zone.But I was born spiritual. I longed to belong to some sort of tradition. I used to sneak away from home on Sundays and go to Catholic Mass with my best friend's family. While I had no education in prayer, I prayed all the time. I prayed over dead birds in our suburban neighborhood; I bought gospel music records; I hung a photo of JFK in my bedroom after he was assassinated and prayed to him. My sisters thought I was nuts.

I once heard an Irish writer say that "an essential element in the life of a writer is to have been an outsider in childhood, to have been given the gift of not belonging." This man's gift had been a father whose job kept the family moving from one town to another. This made him an acute observer of people, and, he said, a better writer. My own childhood predicament of not belonging to a religion, of not being given answers to the big questions, awakened in me an intense yearning to understand the mysterious nature of life and death. I went looking for answers everywhere. I became especially fascinated by prayer: how different people pray, to whom they pray, the answers they receive. Over my many years of searching, I have prayed with Jews at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, with Muslims in Egypt, with Buddhists in Nepal, with Hindus in India. I have engaged in prayer rituals with Native Americans, goddess worshippers, pagans and shamans.

One of my favorite forms of prayer is singing. Sister Alice Martin teaches gospel singing at Omega Institute, the conference and retreat center I co-founded. I have taken her workshops because, for me, singing Christian gospel music is like diving into an ocean of bliss. Sister Alice is an electrifying singer, songwriter and gospel choir leader. When she walks into a room, you sit up a little straighter. When she directs a group of people singing, you never take your eyes off of her. During her workshops, in between leading the group in song, Sister Alice talks about prayer. "Prayer is about being hopeful," she says. "It is not a phone call to God's hotline. It's not about waiting around for an answer you like, especially since sometimes the answer you're going to get is no!"

My favorite advice about prayer from Sister Alice is this: "If you are going to pray, then don't worry. And if you are going to worry, then don't bother praying. You can't be doing both." When I stop and listen closely to what's going on inside my head, I often hear the buzz of worry, like the drone of bees in a wall. That's when I remember Sister Alice's words of wisdom. What would I rather being doing, I ask myself, worrying or praying? I usually choose praying. It's a lot more fun than worrying.

To pray is to let go of your belief that you are in control of your life and to give it over to something more inclusive than your own point of view. It requires a leap of faith. Even if you have only the slightest sense that a higher power is at work in the world, you can still pray. You can name that gossamer belief "God" or not. You can pray to God, or you can pray to your own larger perspective—the part of you that trusts in the meaningfulness of life. I sometimes use Einstein's idea about solving problems when I pray. He said, "No problem can be solved from the same consciousness that created it." My favorite prayer these days is, "Please show me a bigger perspective, a new consciousness."

Sometimes I pray using other peoples' words. Sometimes I pray in silence. Sometimes prayer feels to me like the last resort, an act of throwing up my hands and saying, "You take over now!" Sometimes it feels like a cry of hunger or thirst. Rumi says: "Don't look for water. Be thirsty." Prayer is allowing oneself to be thirsty; it is a longing for something we just cannot seem to find. The Sufis say that our longing for God is God's longing for us. In this way, prayer is like a conversation between friends separated across time and space.

One of the reasons I love prayer is because it is an antidote to guilt and blame. If we are unhappy with the way we have acted or have been treated, instead of stewing in self-recrimination on the one hand, or harboring ill will toward someone else on the other, prayer gives us a way out of the circle of guilt and blame. We bring our painful feelings out into the open and say, "I have done wrong" or "I have been wronged." And then we ask for a vaster view—one that contains within it all the forgiveness we need in order to move forward.

Sister Wendy, a marvelous Catholic nun best known to the world from her books and television shows on art criticism, says this about prayer: "I don't think being human has any place for guilt. Contrition, yes. Guilt, no. Contrition means you tell God you are sorry and you're not going to do it again and you start off afresh. All the damage you've done to yourself, put right. Guilt means you go on and on belaboring and having emotions and beating your breast and being ego-fixated. Guilt is a trap. People love guilt because they feel if they suffer enough guilt, they'll make up for what they've done. Whereas, in fact, they're just sitting in a puddle and splashing. Contrition, you move forward. It's over. You are willing to forgo the pleasures of guilt."

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross is best known as the medical doctor who brought death and dying out of the closet in American culture. She created a curriculum for medical students and sat with hundreds of dying people. Her faith in prayer is legendary. She says, "You will not grow if you sit in a beautiful flower garden, but you will grow if you are sick, if you are in pain, if you experience losses, and if you do not put your head in the sand, but take the pain as a gift to you with a very, very specific purpose." The only thing we can really ask for when we pray is the ability to trust in that greater purpose. We pray to have our hearts opened and our purpose revealed. We pray for gratitude when our life is good and for faith when it is not so good. We pray to trust that our pain is a gift with "a very, very specific purpose."

Vaclev Havel, the former Czech president said something that expresses for me the true meaning of prayer. "It is not the conviction that something will turn out well," Havel says, "but the certainty that something makes sense regardless of how it turns out." We will know if our prayers are working when we are blessed with that kind of certainty. The fruit of prayer is a growing faith that life is an eternal adventure and that we are explorers, always changing, always learning, always open to what we will find beyond the horizon.

Elizabeth Lesser is the author of new memoir Marrow and the co-founder of Omega Institute, America's largest adult education center focusing on health, wellness, spirituality and creativity. She has studied and worked with leading figures in the fields of healing and spiritual development for decades. A former midwife and mother of three grown sons, she is also the author of Broken Open and A Seeker's Guide.

Elizabeth Lesser is the author of new memoir Marrow and the co-founder of Omega Institute, America's largest adult education center focusing on health, wellness, spirituality and creativity. She has studied and worked with leading figures in the fields of healing and spiritual development for decades. A former midwife and mother of three grown sons, she is also the author of Broken Open and A Seeker's Guide.

Keep Reading from Elizabeth Lesser:

How to begin your spiritual journey

10 signs of progress on your spiritual journey

5 ways enough is enough