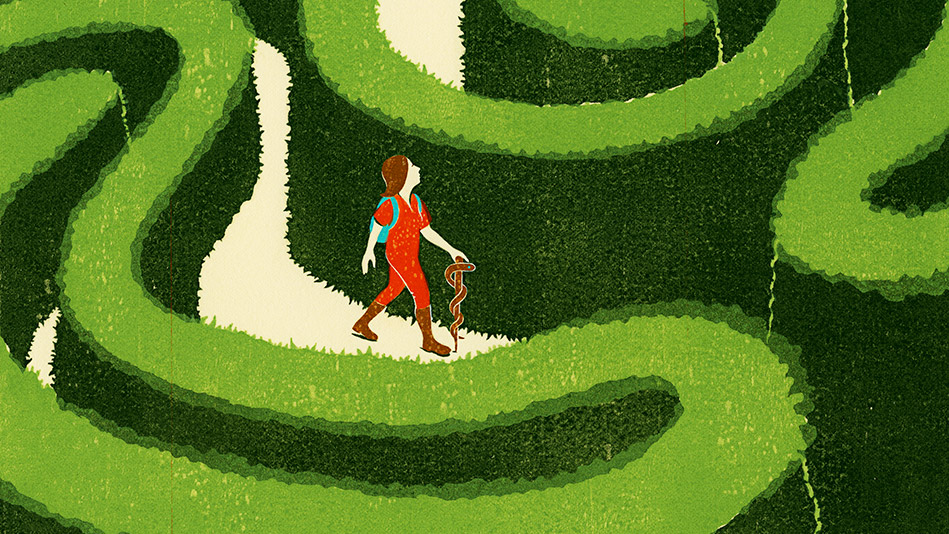

When doctors couldn't cure her, Fiona Maazel forged her own path to recovery. Along her journey—filled with detours, wrong turns and daring adventures—she learned that when it comes to getting well, you are your own best advocate.

Illustration: Dan Bejar

"The plan," she said, "Is to activate your body's resources for self-repair."

"And you can do that from 2,000 miles away?" I asked.

"I just need a photo so I can channel my energy your way."

"Uh-huh."

And so began the first in a series of long-distance phone sessions with a bioenergy therapist. She lived in Canada, I lived in New York, and while I would have preferred that my healing happen in person, she worked for free, so who was I to complain? When she said she was ready, we'd hang up, and for the next 20 minutes I'd sit on the edge of my chair while she worked her magic. Or made a sandwich. Or jumped up and down in her underwear. There was no way for me to know, and I didn't much care.

Six years ago, I was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), an inflammatory bowel disease with no known cause or cure; the conventional treatment involves drugs so toxic they make the disease look good. And so for six years my life has been overtaken by the tragedy of my intestines. Some days I have gone to the bathroom every hour; some nights I have gone to the bathroom every hour. Over the years, I have been so exhausted, crampy, and anxious about my symptoms, I haven't wanted to leave the house.

Things started to go badly when I was 32 and staying at an artists' residency in upstate New York, where I'd gone to work on my second novel. But I couldn't work because I was preoccupied with my body. I had massive diarrhea and an uncontrollable urge to relieve myself. I was also bleeding, and not from where a woman normally bleeds. Bleeding and expelling a purple substance so gory, it was like watching a horror flick in my toilet.

When I got home from the artists' residency, I sought help from a gastroenterologist, who diagnosed me with UC and prescribed cortisone enemas and an anti-inflammatory called mesalamine. The problem only got worse—more bleeding, cramps, urgency. At my next appointment, the doctor suggested the problem was all in my head—that I was "just stressed"—but that if I insisted it wasn't (it's not in my head, Doc, it's in my ass), I should eat more broccoli.

Essentially, he was leaving me on my own. At the time, I didn't realize that when you have a disease with no known cause or cure, you're basically on your own anyway. No two patients respond the same way to treatment for ulcerative colitis, and many patients relapse frequently no matter what drugs they're on.

Enter gastroenterologist number two, Daniel Alpert, MD, who is my dream doctor—smart, attentive, kind. I was grateful to have found someone who was willing to discuss with me, at length, every option Western medicine had to offer. Alpert prescribed steroids, which can be effective but which often come with grim side effects: osteoporosis, diabetes, weight gain, and so forth. And so forth. No one wants to be on steroids for long. In my case, I felt better at first, but the instant I'd taper the dose, my symptoms would return. In the end, it didn't matter because the steroids stopped working entirely after about 18 months. For the next two years, I spent most days thinking about the bathroom the way Tarzan thinks about the vine: "Where is the next one, and will I catch it in time?"

That might sound cavalier; in truth, it was awful. I couldn't go to restaurants for fear of having an accident. An accident, like a toddler. I was panicked about flying. About dating—who could date under these circumstances? About being on the subway. About giving readings and teaching my writing classes. Eventually, things deteriorated to the point where I had to be within three feet of a bathroom at all times. Any longer and I wouldn't make it; even when I did make it, the pain was almost unbearable. Alpert said my intestines had become so inflamed and ulcerated that they could perforate any day. He said I had to do something. But I absolutely did not want to try the options he had in mind: a class of drugs called biologics and another class that the pharmaceutical industry optimistically calls immunomodulators, some of which are categorized by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as Group 1 carcinogens—a group that includes arsenic, asbestos, and plutonium. Plutonium!

"And you can do that from 2,000 miles away?" I asked.

"I just need a photo so I can channel my energy your way."

"Uh-huh."

And so began the first in a series of long-distance phone sessions with a bioenergy therapist. She lived in Canada, I lived in New York, and while I would have preferred that my healing happen in person, she worked for free, so who was I to complain? When she said she was ready, we'd hang up, and for the next 20 minutes I'd sit on the edge of my chair while she worked her magic. Or made a sandwich. Or jumped up and down in her underwear. There was no way for me to know, and I didn't much care.

Six years ago, I was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC), an inflammatory bowel disease with no known cause or cure; the conventional treatment involves drugs so toxic they make the disease look good. And so for six years my life has been overtaken by the tragedy of my intestines. Some days I have gone to the bathroom every hour; some nights I have gone to the bathroom every hour. Over the years, I have been so exhausted, crampy, and anxious about my symptoms, I haven't wanted to leave the house.

Things started to go badly when I was 32 and staying at an artists' residency in upstate New York, where I'd gone to work on my second novel. But I couldn't work because I was preoccupied with my body. I had massive diarrhea and an uncontrollable urge to relieve myself. I was also bleeding, and not from where a woman normally bleeds. Bleeding and expelling a purple substance so gory, it was like watching a horror flick in my toilet.

When I got home from the artists' residency, I sought help from a gastroenterologist, who diagnosed me with UC and prescribed cortisone enemas and an anti-inflammatory called mesalamine. The problem only got worse—more bleeding, cramps, urgency. At my next appointment, the doctor suggested the problem was all in my head—that I was "just stressed"—but that if I insisted it wasn't (it's not in my head, Doc, it's in my ass), I should eat more broccoli.

Essentially, he was leaving me on my own. At the time, I didn't realize that when you have a disease with no known cause or cure, you're basically on your own anyway. No two patients respond the same way to treatment for ulcerative colitis, and many patients relapse frequently no matter what drugs they're on.

Enter gastroenterologist number two, Daniel Alpert, MD, who is my dream doctor—smart, attentive, kind. I was grateful to have found someone who was willing to discuss with me, at length, every option Western medicine had to offer. Alpert prescribed steroids, which can be effective but which often come with grim side effects: osteoporosis, diabetes, weight gain, and so forth. And so forth. No one wants to be on steroids for long. In my case, I felt better at first, but the instant I'd taper the dose, my symptoms would return. In the end, it didn't matter because the steroids stopped working entirely after about 18 months. For the next two years, I spent most days thinking about the bathroom the way Tarzan thinks about the vine: "Where is the next one, and will I catch it in time?"

That might sound cavalier; in truth, it was awful. I couldn't go to restaurants for fear of having an accident. An accident, like a toddler. I was panicked about flying. About dating—who could date under these circumstances? About being on the subway. About giving readings and teaching my writing classes. Eventually, things deteriorated to the point where I had to be within three feet of a bathroom at all times. Any longer and I wouldn't make it; even when I did make it, the pain was almost unbearable. Alpert said my intestines had become so inflamed and ulcerated that they could perforate any day. He said I had to do something. But I absolutely did not want to try the options he had in mind: a class of drugs called biologics and another class that the pharmaceutical industry optimistically calls immunomodulators, some of which are categorized by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as Group 1 carcinogens—a group that includes arsenic, asbestos, and plutonium. Plutonium!

Illustration: Dan Bejar

The alternative to these drugs was surgery to remove all or part of my large intestine, a procedure that could have left me with a colostomy bag forever. In some cases, the surgery doesn't even solve the problem. In other cases, it can cause infertility. So I opted for the drugs, and never felt so debilitated in my life. I was so weak I couldn't hold a toothbrush to my mouth. My heart raced and beat erratically. My skin turned yellow. Within eight weeks, I stopped the drugs and again considered my choices: untreated UC, which can increase the risk of cancer and is impossible to live with; or UC treated via a Western drug regimen, which may also cause cancer and is equally, if not more, impossible to live with. I felt stuck and angry—less at the universe for blighting my life with this stupid disease than with the medical establishment for having nothing better to offer. I had to find something else. And that's when I understood that the only way to move forward was to leave Western medicine behind.

I knew alternative therapies were out there, chronicled on hundreds of websites and blogs: diets and supplements and tinctures and voodoo. Every disease, it seems, gives rise to a subculture of people pioneering new trails toward a cure. Overnight, I became one of those people, one Google search at a time.

I signed up for UC support groups online, posted about my woes, and sought advice. I joined the Supplement Heads, trying L-glutamine, boswellia, aloe, turmeric, vitamin D, colostrum, fish oil, flaxseed, and bromelain. Then I became a Dieter, practicing restrictive meal plans: I cut out all carbs; I ate only rice gruel. Next, I took ambergris, which is essentially whale excrement. I started working with that healer from Canada who'd been recommended by a friend. I went to an acupuncturist who looked at my tongue, told me I was cold, and prescribed herbs that I boiled and drank, feeling like a witch without the vindictive power. I went to a hypnotist, but she spoke in a drawl so comic, I became more anxious, which made hypnotism an unlikely proposition for me. I took almost every probiotic on the market.

Some treatments seemed to work for a spell (for reasons I can't explain, I experienced a modest reprieve while working with the Canadian healer), but nothing stuck. So I kept trying. I continued to hope I'd find something that would work, which meant considering even more radical measures.

My research led me to the "California Man," as he's anonymously known in the press—a guy who, at 29, grew so tired of living with treatment-resistant UC that he decided to try an obscure remedy known as helminthic therapy. In layman's terms: He infected himself with parasitic worms. Within a few months his symptoms improved. Less than a year later he was symptom-free. The FDA hasn't approved helminthic therapy, but scientists at NYU and Tufts University have been researching it for years, thanks to the low incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases in countries where parasitic infection is common. According to helminthic proponents, our immune systems have become too shielded from common pathogens to work properly, so the idea is to reintroduce germs and parasites to the body. For now, though, the theory is just a theory currently being tested in a handful of clinical trials. When I tried to join one of those trials, I was rejected on the grounds that I'd already been on a biologic—which seemed needlessly cruel: Surely most patients will have tried just about everything before they opt to eat worms. Once again, I was on my own, forced to buy pig whipworm eggs online, which begs the question: Where on the spectrum of desperation do you have to be to buy worm ova from some guy in Thailand? The eggs arrived in a thimble's worth of saline solution. It felt like I was sipping a bit of ocean. For all I knew, that's exactly what I was doing. If the treatment worked, it would be not just a godsend but a giant F-you to the Western medical establishment. I'd be celebrated for my brinkmanship. My obstinance would become fortitude, my determination prescience. But after three months, instead of getting better, I felt worse. And I was out thousands of dollars—because what insurance was going to cover worm therapy?

Enter total despair. And a chance encounter at my gym. I was on the elliptical when one of the trainers asked how I was doing. I'm sure she wasn't really asking, but I told her anyway, and then I started sobbing. She knew I'd been having some problems with my stomach. She herself was studying to be a nutritionist, and so she told me to contact a "functional nutritionist," who teaches people how to use food and supplemental therapies to heal themselves, at a company in Portland, Oregon, called Replenish PDX. She said it was the last stop for a lot of desperate people.

Since I'd been on multiple diets and herbs and tinctures and worms, I wasn't keen on contacting Replenish, but I'd run out of options, and theirs seemed no worse than anything I'd already tried. The counselor I ended up with, Megan Liebmann, said she was pretty sure she could have me in remission in three months. Something about cleansing my body of irritants and starting me from scratch. Something about chia seeds and gelatin and slippery elm bark. Stuff I'd heard of before and taken before, but not in the way she planned for me. I was skeptical, but I did as I was told.

The early treatment went something like this: liquids, then three different grains or seeds for a week—quinoa, millet, amaranth—a bunch of vitamins and supplements, and a special probiotic all based on blood tests Liebmann analyzed. I also had to cut out everything enjoyable about food: dairy, gluten, sugar, soy, plus eggs, rice, cranberries, and pineapple, which may or may not have been aggravating my system. This left chicken, fish, turkey, nuts, and vegetables.

Within a few weeks, some of my symptoms relaxed. Trips to the bathroom gradually became less frequent. Things weren't great, but they were better, and I was grateful and ready to accept this as my end point. Then a few months passed. And then one day I woke up and things were different. Normal. No urgent runs to the bathroom. No cramps. No pain. It was my first normal day in about five and a half years. I thought it was a fluke. I went through that day feeling oddly energetic. The next morning I woke up and, again, normal. I'd completely forgotten what it was like to be a healthy person who lives from one hour to the next free of dread and self-disgust. After about three weeks of this, I thought, Oh, my god: remission! Six months later, I'm still going strong.

I don't know if this reprieve is forever. Even if I relapse, I won't return to being the person I was when I started down this path. That person knew nothing about how to advocate for herself. She knew even less about resilience. But illness has a way of estranging us from ourselves. Suddenly I was a person who drank worm eggs. Suddenly I was reckless and weird. Yet I was also aware of what lengths I was willing to go to in order to figure out what was right for me. Not for my friend, who's trying helminthic therapy and feeling great. Or my other friend, whose UC was out of control until she started taking one of those drugs that had failed me. Rather, a treatment plan that is tailored to my needs and composition.

I'm a strong case for why personalized medicine should be the norm and not a luxury for people who can afford it, or a reward for those of us crazy enough to plunge into alternative therapies without a guide. In an ideal world, there would be no "alternative" therapies, just a range of options, each with its own proponents and detractors, and a doctor—a pathfinder—who would size you up and march you down as many roads as it took until you found the right one. Because on this journey you will become your own doctor, therapist, counselor, and fan. You will have to take several leaps of faith and become a person who has no problem taking just one more.

In the end, my leap of faith had to do less with thinking one crazy treatment would work better than others, and more to do with believing this illness could not be what the universe had decided should be my life. That there had to be something better for me out there. After all, at the heart of advocating for yourself is believing that good fortune is always right around the corner, so long as you keep looking. For now, I've found it. But if I have to start looking again, I'm ready for that, too.

Fiona Maazel is the author of Woke Up Lonely (Graywolf Press).

I knew alternative therapies were out there, chronicled on hundreds of websites and blogs: diets and supplements and tinctures and voodoo. Every disease, it seems, gives rise to a subculture of people pioneering new trails toward a cure. Overnight, I became one of those people, one Google search at a time.

I signed up for UC support groups online, posted about my woes, and sought advice. I joined the Supplement Heads, trying L-glutamine, boswellia, aloe, turmeric, vitamin D, colostrum, fish oil, flaxseed, and bromelain. Then I became a Dieter, practicing restrictive meal plans: I cut out all carbs; I ate only rice gruel. Next, I took ambergris, which is essentially whale excrement. I started working with that healer from Canada who'd been recommended by a friend. I went to an acupuncturist who looked at my tongue, told me I was cold, and prescribed herbs that I boiled and drank, feeling like a witch without the vindictive power. I went to a hypnotist, but she spoke in a drawl so comic, I became more anxious, which made hypnotism an unlikely proposition for me. I took almost every probiotic on the market.

Some treatments seemed to work for a spell (for reasons I can't explain, I experienced a modest reprieve while working with the Canadian healer), but nothing stuck. So I kept trying. I continued to hope I'd find something that would work, which meant considering even more radical measures.

My research led me to the "California Man," as he's anonymously known in the press—a guy who, at 29, grew so tired of living with treatment-resistant UC that he decided to try an obscure remedy known as helminthic therapy. In layman's terms: He infected himself with parasitic worms. Within a few months his symptoms improved. Less than a year later he was symptom-free. The FDA hasn't approved helminthic therapy, but scientists at NYU and Tufts University have been researching it for years, thanks to the low incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases in countries where parasitic infection is common. According to helminthic proponents, our immune systems have become too shielded from common pathogens to work properly, so the idea is to reintroduce germs and parasites to the body. For now, though, the theory is just a theory currently being tested in a handful of clinical trials. When I tried to join one of those trials, I was rejected on the grounds that I'd already been on a biologic—which seemed needlessly cruel: Surely most patients will have tried just about everything before they opt to eat worms. Once again, I was on my own, forced to buy pig whipworm eggs online, which begs the question: Where on the spectrum of desperation do you have to be to buy worm ova from some guy in Thailand? The eggs arrived in a thimble's worth of saline solution. It felt like I was sipping a bit of ocean. For all I knew, that's exactly what I was doing. If the treatment worked, it would be not just a godsend but a giant F-you to the Western medical establishment. I'd be celebrated for my brinkmanship. My obstinance would become fortitude, my determination prescience. But after three months, instead of getting better, I felt worse. And I was out thousands of dollars—because what insurance was going to cover worm therapy?

Enter total despair. And a chance encounter at my gym. I was on the elliptical when one of the trainers asked how I was doing. I'm sure she wasn't really asking, but I told her anyway, and then I started sobbing. She knew I'd been having some problems with my stomach. She herself was studying to be a nutritionist, and so she told me to contact a "functional nutritionist," who teaches people how to use food and supplemental therapies to heal themselves, at a company in Portland, Oregon, called Replenish PDX. She said it was the last stop for a lot of desperate people.

Since I'd been on multiple diets and herbs and tinctures and worms, I wasn't keen on contacting Replenish, but I'd run out of options, and theirs seemed no worse than anything I'd already tried. The counselor I ended up with, Megan Liebmann, said she was pretty sure she could have me in remission in three months. Something about cleansing my body of irritants and starting me from scratch. Something about chia seeds and gelatin and slippery elm bark. Stuff I'd heard of before and taken before, but not in the way she planned for me. I was skeptical, but I did as I was told.

The early treatment went something like this: liquids, then three different grains or seeds for a week—quinoa, millet, amaranth—a bunch of vitamins and supplements, and a special probiotic all based on blood tests Liebmann analyzed. I also had to cut out everything enjoyable about food: dairy, gluten, sugar, soy, plus eggs, rice, cranberries, and pineapple, which may or may not have been aggravating my system. This left chicken, fish, turkey, nuts, and vegetables.

Within a few weeks, some of my symptoms relaxed. Trips to the bathroom gradually became less frequent. Things weren't great, but they were better, and I was grateful and ready to accept this as my end point. Then a few months passed. And then one day I woke up and things were different. Normal. No urgent runs to the bathroom. No cramps. No pain. It was my first normal day in about five and a half years. I thought it was a fluke. I went through that day feeling oddly energetic. The next morning I woke up and, again, normal. I'd completely forgotten what it was like to be a healthy person who lives from one hour to the next free of dread and self-disgust. After about three weeks of this, I thought, Oh, my god: remission! Six months later, I'm still going strong.

I don't know if this reprieve is forever. Even if I relapse, I won't return to being the person I was when I started down this path. That person knew nothing about how to advocate for herself. She knew even less about resilience. But illness has a way of estranging us from ourselves. Suddenly I was a person who drank worm eggs. Suddenly I was reckless and weird. Yet I was also aware of what lengths I was willing to go to in order to figure out what was right for me. Not for my friend, who's trying helminthic therapy and feeling great. Or my other friend, whose UC was out of control until she started taking one of those drugs that had failed me. Rather, a treatment plan that is tailored to my needs and composition.

I'm a strong case for why personalized medicine should be the norm and not a luxury for people who can afford it, or a reward for those of us crazy enough to plunge into alternative therapies without a guide. In an ideal world, there would be no "alternative" therapies, just a range of options, each with its own proponents and detractors, and a doctor—a pathfinder—who would size you up and march you down as many roads as it took until you found the right one. Because on this journey you will become your own doctor, therapist, counselor, and fan. You will have to take several leaps of faith and become a person who has no problem taking just one more.

In the end, my leap of faith had to do less with thinking one crazy treatment would work better than others, and more to do with believing this illness could not be what the universe had decided should be my life. That there had to be something better for me out there. After all, at the heart of advocating for yourself is believing that good fortune is always right around the corner, so long as you keep looking. For now, I've found it. But if I have to start looking again, I'm ready for that, too.

Fiona Maazel is the author of Woke Up Lonely (Graywolf Press).

Illustration: Dan Bejar

Understanding Ulcerative Colitis

A brief background on a condition that affects up to 700,000 Americans annually.

What is it?

A chronic bowel disease that causes inflammation in the lower part of the digestive tract, specifically the inner lining of the colon and rectum.

How does it affect the body?

The colon becomes inflamed and forms tiny ulcers, which together can lead to abdominal discomfort, loss of appetite, urgent bowel movements, diarrhea, and bloody stool.

Does anyone know what causes it?

Doctors aren't sure what triggers the condition, which usually surfaces before age 30, but research has found potential links to genetics, autoimmunity, and diet. One study, for example, suggested that roughly 30 percent of cases might be associated with a high intake of linoleic acid (which can be found in red meat, cooking oils, and some margarines).

Why doesn't the body's immune system kick in to fix things?

With ulcerative colitis, the immune system may actually be part of the problem. One theory is that it mistakes harmless food and bacteria in the digestive tract for dangerous invaders, sending the body into attack mode, ramping up inflammation, and irritating the colon.

—Arianna Davis

The Nutrition Cure

Functional nutritionist Andrea Nakayama who founded Replenish PDX, was part of the team that helped Fiona Maazel get well—and she's done the same for hundreds of others. She shares four steps to food-based healing that can help anyone start down a path to recovery.

Step 1: Clear the Playing Field

One of the first things Nakayama recommends to clients is an elimination diet that cuts out seven types of food she finds are most likely to cause inflammation in the body: gluten, dairy, sugar, soy, eggs, peanuts, and seafood. "By clearing out the clutter, we're better able to see what gets resolved and what doesn't," she says. You can remove each category sequentially or cut them all at once. After two to three weeks, gradually reintroduce each food group and note if any trigger your symptoms.

Step 2: Locate the Pain

You can tell a lot about your tummy troubles—and where you need to focus your healing—by pinpointing where discomfort occurs during digestion. "If there's bloating, isolate when it happens and what you've just eaten. For example, fruit can be a common bloater if you have an issue absorbing fructose," says Nakayama. "Constipation, on the other hand, is often linked to dairy."

Step 3: Add a Lemon to Your Morning

"So many people take antacids for heartburn but don't realize that the medication can actually interfere with the process of digestion," says Nakayama. "When the stomach is not acidic enough, it can't properly break down proteins." She recommends starting each day with a glass of room-temperature lemon water—the lemon, while acidic outside the body, is thought to help regulate acidity inside the gut.

Step 4: Look in the Bowl

"I'm a big believer in knowing whether your poop is healthy," says Nakayama. "It's a great indicator of how we're doing digestively." A loose stool may mean you're consuming too much magnesium; a harder one could be a sign you need more fiber or water in your diet. Color matters, too: Black may signal bleeding in the upper GI tract, while green stools may indicate Crohn's disease. Check how things look before flushing, and if you notice anything out of the ordinary, consult your healthcare practitioner.

The E-Patient Revolution

Statistics show that patients are getting deeply involved in their own healthcare long before they enter a doctor's office.

72 percent of Internet users said they looked online for health information.

35 percent logged on specifically to diagnose a medical condition.

23 percent of patients with chronic conditions have looked online to find someone else with their symptoms.

60 percent of e-patients say information they found online affected their treatment decisions.

22 percent of parents admit to seeking medical help on Facebook.

Crowdsourcing Your Care

These three patient-centered sites allow anyone to take greater control of her own health.

PatientsLikeMe.com connects over 250,000 people with more than 2,000 conditions and illnesses so they can swap medical information freely. Some have even created their own observational studies, taking drugs for off-label benefits and comparing notes. Jackie Anderson, 51, of New Hampshire, logged on to find a better way to manage her multiple sclerosis (MS). "Before using the site, I had to give myself daily injections that caused flulike side effects and didn't do anything for my extreme fatigue," she says. "And the drugs cost me roughly $4,000 a month." While reading posts from other MS sufferers, she stumbled upon a drug called LDN, which is FDA approved to treat alcohol dependence but appears to work for MS, too. "I brought the info to my neurologist, who said it was ridiculous snake oil," she says. "But my GP did more research and wrote me a prescription. Two years later, I feel the best I ever have—and the medication costs only $20 a month."

Iodine.com makes it easier for patients to understand prescription drug side effects. When Ruth Dekker, 46, of New Jersey, ran out of Ambien, she started dipping into her husband's stash. But after she began waking up so groggy she felt hungover, she logged on to Iodine, a site launched last July, to see what might be causing the reaction. "I was surprised to learn that a man's Ambien dosage is typically double what doctors prescribe for a woman," she says. "I checked our bottles, and sure enough, his pills were 12.5 milligrams, while mine were only five." The FDA announced the lower standard dose for women last year, but she hadn't read about it. "If I didn't do the research on my own, I might never have known that we couldn't share the same prescription," she says.

CrowdMed.com allows people with undiagnosed conditions to anonymously post their symptoms for roughly 50 "detectives," ranging from seasoned doctors to people with no medical training, to review. In the case of Wyoming native Charlene Delaunay, 61, the site's detectives came to her rescue when her doctors couldn't. Six years ago, she began experiencing a flurry of unexplained digestive issues. "No one could figure out what was wrong with me," she says. "I posted my case on CrowdMed, and within two weeks, they guessed it was permeable intestine." This digestive problem is thought to be caused when toxins pass from the small intestine directly into the bloodstream. Delaunay researched her options and began taking a supplement. "Within two days, I felt better than I had in years."

—Sarah Z. Wexler