The "F" Word

Jackie, a single mother of two, had a successful career and a love for photography, but an unexpected encounter with two violent teenagers would change her life forever.

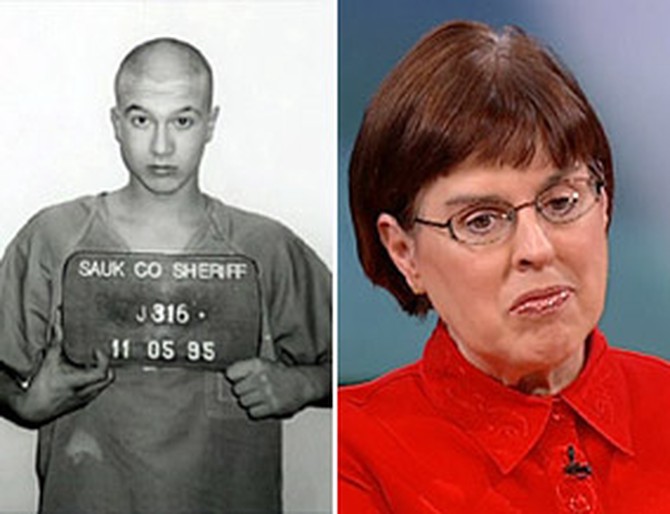

In November 1995, while taking a nap at a friend's house, Jackie awoke to find then 16-year-old Craig Sussek and 15-year-old Josh Briggs in the garage trying to steal her car. The teens forced Jackie inside and told her to lie on the floor. Craig placed a pillow over Jackie's head and left her for dead after shooting her at point-blank range. The teens fled, and Jackie's friend discovered her minutes later.

Doctors told Jackie's family she had only a 2 percent chance of survival. After spending six weeks in a coma, Jackie awoke with severe brain injuries. For the next nine months, Jackie lived in a rehabilitation center, where she had to learn how to talk, eat, walk and even swallow again.

Jackie is now partially paralyzed on the right side of her body, which causes intense pain. "I liken it to a thousand needles on my right side. It is constant," she says. Her speech is impaired and she is legally blind. Everyday actions, like tying her shoes, are still a challenge for Jackie. "When I was shot, that changed everything. They took away everything," she says. "But I got it back."

In November 1995, while taking a nap at a friend's house, Jackie awoke to find then 16-year-old Craig Sussek and 15-year-old Josh Briggs in the garage trying to steal her car. The teens forced Jackie inside and told her to lie on the floor. Craig placed a pillow over Jackie's head and left her for dead after shooting her at point-blank range. The teens fled, and Jackie's friend discovered her minutes later.

Doctors told Jackie's family she had only a 2 percent chance of survival. After spending six weeks in a coma, Jackie awoke with severe brain injuries. For the next nine months, Jackie lived in a rehabilitation center, where she had to learn how to talk, eat, walk and even swallow again.

Jackie is now partially paralyzed on the right side of her body, which causes intense pain. "I liken it to a thousand needles on my right side. It is constant," she says. Her speech is impaired and she is legally blind. Everyday actions, like tying her shoes, are still a challenge for Jackie. "When I was shot, that changed everything. They took away everything," she says. "But I got it back."

Despite the physical struggles she faces as a result of the shooting, Jackie says she forgives her attackers. "I think I would be nuts if I hadn't forgave them," she says. "I forgave them immediately so I could get on with my life."

The same night Jackie was shot, police arrested and charged Craig and Josh with attempted murder. Both teens were convicted and sent to prison. Two years after the shooting, Jackie visited Craig in prison to find out why he had shot her and to let him know she forgave him. "He had so much guilt," she says. "I reached across the table, and I offered him my hand. He couldn't look me in the eye. Then about a minute or two [later], he had taken my hand and all the while he cried."

Craig, who is serving an 80-year sentence, says he was initially terrified when he heard Jackie was coming to visit. He says he expected screaming and was surprised to find forgiveness instead. "For my 16 years when I was out there before this happened … I didn't have a lot of affection shown towards me, so I didn't know how to deal with that," Craig says. "When Jackie said that she forgave me, basically it just blew my mind and my whole understanding. I had no idea how to react to something of that magnitude."

Although Craig says he hasn't forgiven himself, he says Jackie's unconditional love has given him hope. "When Jackie forgave me, I was able to see that there is a future, and I can strive to be a better person and reach that future," he says.

The same night Jackie was shot, police arrested and charged Craig and Josh with attempted murder. Both teens were convicted and sent to prison. Two years after the shooting, Jackie visited Craig in prison to find out why he had shot her and to let him know she forgave him. "He had so much guilt," she says. "I reached across the table, and I offered him my hand. He couldn't look me in the eye. Then about a minute or two [later], he had taken my hand and all the while he cried."

Craig, who is serving an 80-year sentence, says he was initially terrified when he heard Jackie was coming to visit. He says he expected screaming and was surprised to find forgiveness instead. "For my 16 years when I was out there before this happened … I didn't have a lot of affection shown towards me, so I didn't know how to deal with that," Craig says. "When Jackie said that she forgave me, basically it just blew my mind and my whole understanding. I had no idea how to react to something of that magnitude."

Although Craig says he hasn't forgiven himself, he says Jackie's unconditional love has given him hope. "When Jackie forgave me, I was able to see that there is a future, and I can strive to be a better person and reach that future," he says.

Dr. Robin holds Jackie up as an example of the power of forgiveness that comes from letting go of anger and moving on. "I'm so moved, and I was sitting here, Jackie, looking at you and listening to you and thinking what a brilliant example you are for all of us who complain about small things and aches and pains," Dr. Robin says. "And here you are, a living testimony to us … saying that forgiveness is a choice. And when we choose not to forgive someone … we've made a choice to harbor anger, and really, a choice to die."

As for Craig, Dr. Robin feels like he was actually in prison before he committed any crime. "Your spirit was in prison. Your mind was in prison. Your body. I mean, you weren't really living. And what is interesting is that, unfortunately, Jackie and your tragedy, Craig, was your ticket to reengage with the fact that you're a human being," she says. "So now, even though you're incarcerated, you are more free today than you were 12 years ago when you shot Jackie. And it's a new way to begin to look at who you are, what's in front of you, the fact that you do have a future."

As for Craig, Dr. Robin feels like he was actually in prison before he committed any crime. "Your spirit was in prison. Your mind was in prison. Your body. I mean, you weren't really living. And what is interesting is that, unfortunately, Jackie and your tragedy, Craig, was your ticket to reengage with the fact that you're a human being," she says. "So now, even though you're incarcerated, you are more free today than you were 12 years ago when you shot Jackie. And it's a new way to begin to look at who you are, what's in front of you, the fact that you do have a future."

July 7, 2005, started out just as a normal day in London for Gill. She was dreaming of her upcoming wedding as she headed to work on the city's Underground subway system. As the train pulled into a station, she says she heard "a snap—no bang, no noise, nothing. And suddenly we were all in a completely different place."

Terrorist suicide bombers detonated four bombs that day on three subway cars and on a double-decker bus. When that was over, 56 people were killed—including 26 on Gill's train car—and more than 700 were injured.

As people around her screamed and the car filled with black smoke, Gill's legs were badly hurt and bleeding heavily. She says she felt two competing impulses, almost like voices speaking to her. "It was like I was being presented with two approaches—the aisle of death and the aisle of life. The aisle of death looked fantastic. … The voice of life was quite agitated. It was quite angry at me saying, 'No, you are not to die now.' It was like a little lightbulb moment for me that my death actually isn't about me. Death is about the people you leave behind to mourn. And that's who kept me going."

With a determination to live, Gill tore her scarf to make tourniquet for her legs. After rescuers arrived, they pulled her from the wreckage and rushed her to the hospital. On the way, Gill's heart stopped three times and she lost 75 percent of the blood in her body. Doctors had to amputate both of her legs below the knee, and today she walks with the help of prosthetics.

Terrorist suicide bombers detonated four bombs that day on three subway cars and on a double-decker bus. When that was over, 56 people were killed—including 26 on Gill's train car—and more than 700 were injured.

As people around her screamed and the car filled with black smoke, Gill's legs were badly hurt and bleeding heavily. She says she felt two competing impulses, almost like voices speaking to her. "It was like I was being presented with two approaches—the aisle of death and the aisle of life. The aisle of death looked fantastic. … The voice of life was quite agitated. It was quite angry at me saying, 'No, you are not to die now.' It was like a little lightbulb moment for me that my death actually isn't about me. Death is about the people you leave behind to mourn. And that's who kept me going."

With a determination to live, Gill tore her scarf to make tourniquet for her legs. After rescuers arrived, they pulled her from the wreckage and rushed her to the hospital. On the way, Gill's heart stopped three times and she lost 75 percent of the blood in her body. Doctors had to amputate both of her legs below the knee, and today she walks with the help of prosthetics.

Despite her tragedy, Gill says she forgives the terrorists. "I would love to have had the opportunity to have met the bomber," she says. "I think [the] textbook situation of forgiveness is that it's lovely to be able to meet the person who has done a crime to you and to open your arms and to show that unconditional love, which I think is amazing. I can't do that because my bomber is dead."

Gill now works as an ambassador to the United Kingdom-based charity Peace Direct and wrote One Unknown about her experiences. She says she has found other messages of hope in the tragic event that nearly cost her, her life. Gill says she takes a lesson of strength from the work of the paramedics who saved her.

"They didn't know who I was. I was an unknown person. They risked everything to save me and they never gave up, and that's what I think is miraculous," she says. "Even right down to the heart stopping for the third time, there was a moment where two paramedics were actually having a conversation over my body of, 'Let's change her tag to a black tag. Pronounce her dead.' And someone else rushed over and said, 'No, no, no. I've been working on her. I'll take over.' And I now know these people. They're my dearest friends. And you just think, 'How amazing? They never gave up.'"

Gill now works as an ambassador to the United Kingdom-based charity Peace Direct and wrote One Unknown about her experiences. She says she has found other messages of hope in the tragic event that nearly cost her, her life. Gill says she takes a lesson of strength from the work of the paramedics who saved her.

"They didn't know who I was. I was an unknown person. They risked everything to save me and they never gave up, and that's what I think is miraculous," she says. "Even right down to the heart stopping for the third time, there was a moment where two paramedics were actually having a conversation over my body of, 'Let's change her tag to a black tag. Pronounce her dead.' And someone else rushed over and said, 'No, no, no. I've been working on her. I'll take over.' And I now know these people. They're my dearest friends. And you just think, 'How amazing? They never gave up.'"

How can Gill possibly forgive the people who nearly killed her…and now force her to live the rest of her life without legs? Forgiveness does not mean that you accept or condone the actions against you. "People are afraid if they forgive someone, it's the get out of jail free card," Dr. Robin says. Instead, "it's the get out of jail card for the person who would harbor the unforgiveness. And what you're really saying is no one is worthy of your life, your energy, your peace, your power. And as long as you're bitter or resentful, someone owns you."

Gill says she's ready to move forward with her life. "My legs have gone, but I'm not going to let this destroy the rest of me," she says. "I'm so lucky to have had this life number two. That's how I see it—that I've had life one, the bomb, and now it's life two. … I feel I've been given this gift and I have to honor that and live the best life possible. And that doesn't mean carrying around a sack of potatoes of hatred and bitterness."

Gill says she's ready to move forward with her life. "My legs have gone, but I'm not going to let this destroy the rest of me," she says. "I'm so lucky to have had this life number two. That's how I see it—that I've had life one, the bomb, and now it's life two. … I feel I've been given this gift and I have to honor that and live the best life possible. And that doesn't mean carrying around a sack of potatoes of hatred and bitterness."

"About a year ago, I was leaving a restaurant at lunch and I got held up at gunpoint," says Harold, an Oprah Show audience member. Then, he says, the assailant had him kneel down in the parking lot and put the gun by his head. "I thought for many seconds there, 'I don't know if I'm going to make it to see my family tonight,'" Harold says. "All I could think about was I've got to make it to be with them at home tonight."

Harold says that the mugger then took his wallet and phone and demanded his watch. "I looked at him, and for some reason, I saw there was a human being there," he says. "And even though I was very afraid because he had sworn to me he'd shoot me about 10 seconds before, I told him, 'My dad gave me this watch before he died.' He looked at me and he said, 'You can keep the watch, man.'"

When he finally returned safely to his family, Harold said his son asked what he'd do if he encountered the thief again. Wouldn't he want to get revenge?

"I said I would tell him, 'I forgive you and I thank you for having a little bit of humanity with something that meant a lot. I thank you for not trying to cover your tracks by shooting me and letting me continue on and be with my family.' … And it has not troubled me since then," Harold says. "I feel lucky that I'm here today. I feel lucky that I've had every day since that day."

Harold says that the mugger then took his wallet and phone and demanded his watch. "I looked at him, and for some reason, I saw there was a human being there," he says. "And even though I was very afraid because he had sworn to me he'd shoot me about 10 seconds before, I told him, 'My dad gave me this watch before he died.' He looked at me and he said, 'You can keep the watch, man.'"

When he finally returned safely to his family, Harold said his son asked what he'd do if he encountered the thief again. Wouldn't he want to get revenge?

"I said I would tell him, 'I forgive you and I thank you for having a little bit of humanity with something that meant a lot. I thank you for not trying to cover your tracks by shooting me and letting me continue on and be with my family.' … And it has not troubled me since then," Harold says. "I feel lucky that I'm here today. I feel lucky that I've had every day since that day."

Two women in the audience, Laurie and Zina, ask Dr. Robin how they can

approach family members who tend to not easily forgive.

The first step, Dr. Robin says, is to have a conversation and validate whatever their reason is for feeling injured by them without condemning them. "Forgiveness is a journey. And part of the journey is about acknowledging the suffering, the pain, whatever it is that your family … feels injured by," Dr. Robin says. "So you want to start by just saying to [them], 'We really get that you feel hurt, that you feel betrayed, that you feel … whatever it is [they're] feeling."

If they continue struggling to forgive, Dr. Robin says to tell them how holding a grudge is a waste of time and energy. "If you invite them to give up the exhaustion, to give up the banner of unforgiveness and pick up the banner of living, that would really be the next step," she says. "Because a lot of people think that they are empowering themselves by holding onto the grudge."

The first step, Dr. Robin says, is to have a conversation and validate whatever their reason is for feeling injured by them without condemning them. "Forgiveness is a journey. And part of the journey is about acknowledging the suffering, the pain, whatever it is that your family … feels injured by," Dr. Robin says. "So you want to start by just saying to [them], 'We really get that you feel hurt, that you feel betrayed, that you feel … whatever it is [they're] feeling."

If they continue struggling to forgive, Dr. Robin says to tell them how holding a grudge is a waste of time and energy. "If you invite them to give up the exhaustion, to give up the banner of unforgiveness and pick up the banner of living, that would really be the next step," she says. "Because a lot of people think that they are empowering themselves by holding onto the grudge."

Published 01/01/2006