It's the eternal dilemma of the journal keeper and letter writer: Toss your private papers into the fire, or leave them for your heirs to be captivated (or scandalized, or bored) by?

I was 51 when I began to keep a journal. I think it was because I was in a panic about my first novel. And because my father had recently committed suicide. I needed somewhere to cry and complain, a place where I didn't have to perform. Unlike a therapist, my journal didn't give advice or charge a fee. Much of the writing was fueled by anger, frustration, and despair—which is why if I died tomorrow, I'm not sure I would want my husband and daughters to read what I wrote. Still, I never dreamed of destroying my journals until a friend accidentally discovered a three-page rant his mother had scrawled many years before she died."My children are takers," she wrote. "They're not good-natured. They're selfish, self-centered, self-indulgent, and only need me when they want money."

One of her sons was so upset by the letter that it catapulted him back to the "pimple-faced rage" of adolescence. But his older brother cherished the chance to "hear" his mother's voice again. "It was so her," he says. "Angry, funny. Like a child lashing out. And when I read her words, I could feel her presence."

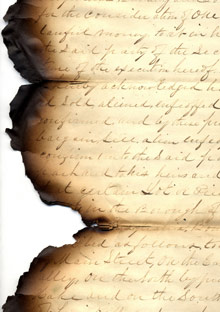

It was that intensity of presence that overwhelmed me when I read my parents' love letters, which my mother had threatened to throw away before she died. "Please don't," I had begged as we stood in her closet, the box of perfume-scented letters tantalizing me from a shelf. "Why would you care if I read them after you were dead?"

Soon after her death, I spent a voyeuristic week devouring my parents' words, catching glimpses of who they were before I was born.

"The juice is squeezed / the coffee's made / I'd rather stay in bed well laid," my father had written in his delicate hand on a scrap of paper the year they were married.

"I know I'm sterile," my mother lamented when she still wasn't pregnant six months later.

"Don't be discouraged, baby," he reassured her. "It's fun trying."

Unlike me, my older brother had no desire to creep inside our parents' heads (or bed). "I don't care to read that stuff," he told me with a squirm in his voice. "I find it a real intrusion on their privacy."

Then why, I wonder, did Mama leave the letters for me to read? If she'd wanted to protect her and my father's privacy, she'd have destroyed them no matter how much I begged.

And what about my own children—would they shy away from reading my journals after my death, or would it be a welcome chance to learn more about me?

My older daughter, a yogini and student of Sanskrit, tells me outright that she intends to burn her own journals ("to set the words free") and has no interest in reading mine. "I don't believe there are family secrets," she says. "I think we all learn what we're supposed to learn when we're ready to learn it. Going through some old papers isn't going to tell me anything I don't already know." But my younger daughter, who like me is sentimental and appreciates gossip, says she'd feel cheated if I destroyed my journals—even if some of the contents were difficult to take. "I guess the only thing that would really upset me," she says, "is if I read something negative about me."

Her response reminded me that the journal keeper isn't the only one who's narcissistic. In the seventies, my best friend's artist husband had an exhibit where he displayed 30 years of journals that included photos, poetry, and descriptions of his extramarital affairs. "You wouldn't believe how transfixed people were," his now ex-wife says. "Not because they wanted to read about him but because they wanted to see what he said about them."

I can understand how for some, the journal is a way to put on a show, to fashion a persona for an imagined audience. But for me the opposite was true. Coming from a family of "performers," where every dinner was a "show," I was relieved to have a place where I didn't have to worry about what other people thought, a place where I could crawl into myself. For years I have avoided going back through those raw, unedited pages, afraid to relive painful experiences or see what a fool I was. But when I started thinking seriously about the future of my journals, I overcame my resistance and began to read. What I found was a writer who berated herself for not writing, a mother who blamed herself for not being good enough, a wife who was exasperated with her husband, and a daughter who struggled to be her own person. The self-criticism is leavened with analyses of dreams and descriptions of fabulous meals. In some places, I am amazed by the quality of the writing; in others, I am appalled by how crushingly boring it is. Sometimes I think I shouldn't wait until I'm dead to share these pages; other times I think I'd be doing my survivors a favor to destroy them now.

I have friends who react to in-flight turbulence with the dread that the plane will crash and they won't have gotten rid of their personal papers. "I would die if my husband/parents/kids ever read that stuff!" they say. I'd like to remind them that you can't die twice—and that if they want to go down with their secrets, they should destroy their papers before they board the plane. But every time I think about burning my own journals—or ripping out the pages that might offend someone I love—there's a little person inside me who says no. The journals are a part of me, a reflection of the good and the bad, and to destroy them would be to destroy a part of myself.

I have wondered if my mother was flirting with immortality when she left me her letters. And if I, too, harbor the same conceit. But if someone reads my journals after I'm gone, I hope they'll glimpse a woman who was less interested in cheating death than in discovering the meaning of her life.

Mary Pleshette Willis contributes frequently to the City section of The New York Times and is the author of the novel Papa's Cord (Knopf).