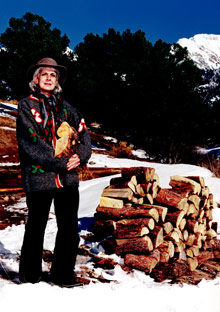

Photo: Mackenzie Stroh

Life: mushy-gray. Spirit: empty. Solution: get back in touch with God. Beverly Donofrio took off six months to go monastery-hopping, and discovered peace, clarity, connection, grace, and, finally, a kind of hush all over her world.

Two winters ago the world turned flat and tuneless on me, and it made no sense. Home was a lively, supportive expat community in an old colonial town in Mexico. I soaked in hot springs, hiked, practiced tai chi, wrote during the day, and spent most of my nights with friends. There were dinners, concerts, readings, margaritas watching the sunset, but it had all gone gray.Not too long before, I could tap into a presence, a feeling of love—some would call it spirit, I called it God. I'd become one of those lucky people who knew as sure as the moon gets full that God exists and is in me and everyone else. But I couldn't sense the presence anymore. I meditated three times a day and felt no peace. I wasn't bored, exactly; it went deeper than that. I needed a God infusion. And so, while visiting my 8-month-old grandson in Brooklyn and needing to be alone to meet a deadline on a book, I had an inspiration. I wrote to the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut, a monastery of 40 Benedictine nuns who run a working farm on 400 acres, and requested a retreat. They wrote back immediately, offering two days.

Turning into the driveway, I spotted my first nun, speeding by in a pickup, a sweatband over her wimple, and something about that incongruity, about observing ancient practices in a speeding world, about working the land, praying with song, practicing silence, living on a commune and never leaving, quickened a longing in me.

For three services a day I sat in the chapel and observed the nuns behind a wrought-iron grill, chanting the hours in Latin. I felt the envy I used to feel in junior high school when I pored over the pictures in my brother's high school yearbook. I wanted to skip from layperson and observer to contemplative singing praises to God with my sisters.

Between chapel visits, I did manage to almost finish my book draft and to plant 200 lilies in the forest. The carpet of leaves soaked my knees, and birds twittered above me, as I buried each bulb thinking about stasis and new life, stagnation and transformation, dark nights and how they too can bloom—into holy joy.

I was aware of how I tend to imagine the future through rosy-colored glasses; high school, after all, had turned out to be closer to hell than heaven. Still, to test the waters once I was back in Brooklyn, I told my son how attracted I'd been to the monastery, and wondered what he thought about the possibility of my joining a place where I'd be cloistered—where he could visit me but I'd rarely be able to visit him. He put his hand on the counter to steady himself. "You know I'll feel abandoned," he said. "You won't see Zach graduate. You won't come to his wedding."

Most sadhus, or holy men, in India have had careers and families, but toward the end of their lives they leave it all to walk the path of enlightenment. Christ said a few times in a few different ways that you must be willing to give up everything, not only your riches but your family, too. You must lose your life to gain it. I understood how one must make God the focus, the ground zero of your being. But I also understood that God is love and doubted that he would ask me to abandon my grandson and my only child, who had no other parent.

I went back home and was distraught to find how lonely I felt despite my busy social world. The contemplative nun fantasies began to bombard me nonstop. Wearing a habit definitely factored in, which probably had something to do with my brother winning a nun doll at a local TV clown show when I was 8 and his refusing to give it to me. (I can still picture the little pearly beads on her rosary belt.) Plus, if I never had to sit for another expensive haircut in my life I'd be ecstatic. Did I really want to pick up another Vogue to gauge the length of hemlines this season—ever again?

I was 55 and my priorities had changed. The prospect of being freed from small conversations, maybe from all conversations, filled me with awe. I pictured myself walking down a hushed hallway, passing another nun and merely nodding. I craved silence and realized that I probably always had.

I decided to take six months to sample the life—and, in case I really was being called, see if I'd be led to a monastery that would have me.

An obsessive search on the Internet yielded a few discouraging facts. The monasteries all seemed to have age ceilings, by whose standards I was a dinosaur. And the contemplative orders were cloistered, which would mean, basically, no visits to my family. But since a rock-solid faith was what I aspired to, I tried to believe, and often succeeded, that if God wanted me in a monastery, God would work it out.

I can't re-create exactly the process by which I came to choose the places I did because logic was not much applied. For example, in Snowmass, the first place I visited, there was a Trappist monastery for men, which surely would not invite me to join. I stayed at Nada, a hermitage in the Carmelite tradition with women and men. I visited my friend Estrella—a hermit nun in an order of one. I wanted to try at least one place run by Catholics who were not in community, that was more a house of prayer, catering to retreatants. And I went to a monastery of Benedictine women who incorporate Eastern practices into their worship.

At Snowmass the snow fell and it fell. I covered my face with my scarf and dug my hands deep into my pockets as I walked to Lauds and Mass, to Vespers and Compline, down the mountain to the chapel whose lights beckoned in the dark. The Psalms were in English and I sang along with the monks and other visitors from a songbook, trying to blend my voice with theirs so well it disappeared. I cooked meals in my little octagonal hermitage and resumed my practice of meditating three times a day. But every time I sat on the cushion, my teeth began to ache. I thought it might be because my ego was threatened and trying to distract me, or maybe toxins were being released. I observed how the pain did make it harder to sit on the cushion, but the pain also took me deeper and made me more tender. I'd read somewhere that Christ's beginning point was not sin but suffering, that God didn't prevent pain but stood with you. I'd also read that one should try to talk to God as an intimate, as a friend, to bare your soul, to tell the secrets of your heart. I avoided this conversation. It was too hard; I had no idea why.

In the silence of Snowmass, my own silence shouted so loudly I heard the echo of all the words left unspoken in every relationship of my life. This realization made me so sad my body fisted into a ball as I wept. When I finally stopped, I wept all over again—from relief, because I remembered how deeply I did believe that anything is possible with God. Even intimacy. And I was not alone.

The night I arrived at Nada Hermitage was moonless and pitch-dark, but luckily Sister Kay, a radiant young woman in jeans, was waiting to show me the way. She said I'd find all the information I needed in a notebook in my hermitage, but she wanted to make sure that I understood that the monks were in the middle of hermit week, and if people didn't say hello it was not personal. She said that there were also hermit days during each week, and, in fact, if I wanted to be a hermit the entire time and never speak to a soul, I was welcome to do this.

In the light of morning I discovered that my little cabin—with a desk, chair, bed, two-burner stove, and tiny refrigerator—was backed into a sand dune. Immediately to the east was a 14,000-foot big-shouldered mountain and to the west the vast San Luis Valley, where the deer and the antelope play, just like in the song, only there are elk there, too.

I began to read spiritual classics with a hunger I hadn't experienced since I'd been a stuck young mother at 17 and literature lit up my life. Back then at the public library I'd found Dickens and Austen, then Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Virginia Woolf. Now I read contemplatives and mystics I found in Nada's library: Thomas Merton, Saint Teresa of Avila, Saint John of the Cross, Evelyn Underhill, and Brother Lawrence. One of the ancients said, "If you wish to attain God, there are two things you must know. The first is that all efforts to attain God are of no avail. And the second is that you must act as if you did not know the first." I believed that if I made room in my life for a practice of meditation, prayer, walking, reading, listening in the silence, one day the spiritual life would become real. As Plotinus said back in the third century about the experience of unity, "We ought not to question whence [it comes]; there is no whence, no coming or going in place; now it is seen and now not seen. We must not run after it, but fit ourselves for the vision and then wait tranquilly for its appearance, as the eye waits on the rising of the sun, which in its own time appears above the horizon...and gives itself to our sight."

And so I listened in the silence and heard my own breath, a bird, a whisper of wind. I tried to remember to be grateful and send up little prayers of thanks all the day long, to look deeply at things, and to see the sacred in the very day. Then one afternoon it began to snow. I stood at my window, and all of a sudden everything slowed so that I could see flake behind flake for miles as though in a freeze-frame, but all of them moving ever so slowly, distinct and separate, together falling. Snow.

It was just as the mystic Bede Griffiths described these breakthrough moments, "...a veil has been lifted and we see...behind the facade the world has built round us.... It is impossible to put...into words; it is something beyond all words...in the language of theology they are moments of grace."

I wept for the gift of it, for the sight of a bunny darting by, a deer up on the hill nibbling on a weed. When it came time to leave Nada, I didn't want to. But I'd been told that the community was in no position to consider a new member—of any stripe. Their founder had been ousted and removed from the priesthood a few years before. The community was still reeling from it and trying to reimagine itself, a task that the nine members, five in Colorado and four in Ireland, would gather to carry out in the coming year.

I moved on to Missouri to visit Estrella, the hermit nun in an order of one, whom I'd met a few years before in Mexico, where she helped organize a hospital and midwifery school.

Our first evening, after Estrella lit candles and served and blessed our thick steaming vegetable soup, she prayed that my stay would give me clarity, and hoped I would talk as much as I wanted about all that was happening inside, about dreams, about anything, so she could help me with my spiritual discernment. I had a dream about caring for a baby I'd neglected. "It's God," Estrella said. I had another dream in which there was a stick in my salad. I poked it with my fork to bat it away, but it turned into a beautiful, regal bug, bedecked in jewels, wearing a crown. "That's you," Estrella said. "God made you a peacock. Somehow you will use that."

Now I grilled her about her nunhood, and she explained how after her three daughters were grown, she had visited 30 monasteries and convents looking for the one that was right for her and never found it. So she wrote her own vows, and with the blessing of her spiritual director, a Trappist hermit priest, she founded her own order. No bishop or pope has recognized her, but Estrella is the holiest person I know. Her altar is lit by candles that are never extinguished, and lined with pictures of those who have asked for her prayers. The phone rang with prayer requests every day. She counsels mothers, and while I was there she gathered food and clothes to bring to a single mother in need. Like the simple Brother Lawrence, she is in a constant dialogue with God. We practiced yoga together, prayed over our meals, sent up prayers of gratefulness for the littlest things: the honey in our tea, the warmth of her house, the car starting in the morning.

On Estrella's holy land, I began taking my lead from Julian of Norwich, a 14th-century woman mystic who said, "God wants us to allow ourselves to see God continually. For God wants to be seen and wants to be sought. God wants to be awaited and wants to be trusted."

One morning I awoke knowing what I had to do: make a commitment to God as I was never able to make to any other love in my life except my child. I wrote down three vows—Chastity, Silence, Constant Prayer—then read them to Estrella, who took my hands in hers and said, "I am so happy for you!" We drove to Estrella's spiritual director, who blessed the vows in a Mass in his living room. No church official would recognize me as one, but that didn't matter, I was a nun.

At the Desert House of Prayer near Tucson I continued my study, my meditating, my silence. It was cold in January, and after Lauds and Mass in the morning the retreatants, sometimes as many as 20 of us, gathered silently to take our own breakfasts. There is a fire in the living room one can sit in front of, but in the kitchen if you sit at the table you can watch the birds at the feeders hanging from a big old pal-o-verde tree.

The king of the birds was a cardinal, magnificently large and regally red. One day I spotted him sitting in another tree, yards away, minus his tail. He could still fly, and balance, but he was clearly diminished and waited till the crowd of birds dispersed before he came around to scavenge for seeds. I was sad for the bird, and concerned that he would die. I wondered if this diminishment of his abilities was a prelude, a preparation for death. And I wondered, too, if my own aging, the imminent diminishment of my own abilities, had at bottom been what fueled my desire to leave the world and draw closer to God. I also wondered if God had been calling me all along and I'd never heard. I'll never know. But I do know that by the time I left a month later, that big old cardinal had begun growing another tail. And I was thinking that instead of embarking on a Prelude to the end, I was beginning Book Two, in which God was my coauthor.

At Osage, in Oklahoma, the last monastery I visited, I grew fond of Father John. He was old himself and had once left the priesthood to teach 3-year-olds at a Montessori school. There was still much of the 3-year-old in Father John, who during Mass would give his homily, then open it up to the crowd, saying, "I'm not the expert here; I'm sure you all have things you want to say." And we did.

Father John told me that "knowing God through the intellect is like someone telling you all about her friend, but you don't know the friend until you meet him and experience him." This seemed to describe precisely how I was different at the end of my pilgrimage than I'd been at the beginning. God was here and God was somehow communicating to me that if I had faith the size of a mustard seed I could move mountains and learn to love, to be loved, to give and to receive, to be, as Mother Teresa said, Christ's representative in this world.

Still, I was in a bit of a panic, thinking about ending my extended retreat and going back to my life. I had no invitation from anywhere, although it did seem to me that I could continue to be a nomad, moving from monastery to monastery. But Nada, where I'd had the moment of grace in the midst of the snow, seemed to beckon me. So I wrote to the monks and proposed that I pay a little money every month, work a bit, gardening and running errands, and see how it plays out.

The community responded that they thought it was a very good idea. I rented my house and have now been in residence for eight months.

A mountain lion was recently spotted sleeping in a tree near my hermitage. I have climbed up to an alpine lake alone, and observe silence one week every month and four days of every week. I have no doubt that God, whom I sometimes call Pumpkin Pie and Bundle of Love, is here, just as he/she/it always was. But in a place where you can hear your own bare feet on the floor, where the stars touch the horizon all around, and hail can fall at any moment, in a place where the spirit becomes the reason and the focus, God is so much easier to know.

Beverly Donofrio's most recent children's book, Thank You, Lucky Stars (Random House), was published in January 2008.