Five writers recall their darkest hours and the poems that sustained them.

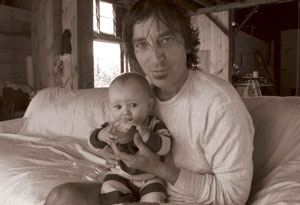

Photo: Lili Taylor

Nick Flynn finds the father within.

Three years ago, I was walking with a friend when we ran into Robert Hass, the former U.S. poet laureate. I'd met Hass a few times, and his work meant a lot to me. When he asked me how I was, I said, as I did in those days, that I was to have a child soon. I didn't tell Hass that the very word father felt ineffable in my mouth. My own father had been absent my whole life, wandering in a type of fog I couldn't enter, though I had tried, in my own way, over the years. The idea that I was to become one soon was difficult for me to imagine—or what I imagined was that within it I would find only wreckage.

While I said none of this to Hass, I must have said something, for he got very excited, and reached into his satchel, and pulled out a copy of George Oppen's "Sara in Her Father's Arms," and read it to me, right there. Cell by cell the baby made herself...it was as if he, or Oppen, was telling me that it was already out of my hands, that all I had to do was show up, to hold this as-yet-unborn girl in my arms, and she would teach me everything I needed to know. I held on to it, this poem, and I still do, even now, three years later, as my daughter brings me all the words she has found that day—words! There will be no other words in the world / But those our children speak.

Sara in Her Father's Arms

Cell by cell the baby made herself, the cells

Made cells. That is to say

The baby is made largely of milk. Lying in her father's arms, the little seed eyes

Moving, trying to see, smiling for us

To see, she will make a household

To her need of these rooms—Sara, little seed,

Little violent, diligent seed. Come let us look at the world

Glittering: this seed will speak,

Max, words! There will be no other words in the world

But those our children speak. What will she make of a world

Do you suppose, Max, of which she is made.

—George Oppen

Nick Flynn's most recent book of poetry, The Captain Asks for a Show of Hands (Graywolf), came out in February.

Next: The poem that helped Timothy Shriver mourn his mother

Photo: Getty Images

Timothy Shriver experiences waves of grief and joy.

When I was a child, my family went to Cape Cod every summer. There I discovered that our clan included loads of cousins and uncles and aunts and animals of every shape. I was taught that chaos and competition were family values. And I learned that we all loved the sea. Somehow, the sea was about us—our past, our exuberance, our frailty, our longing.

I first read Emily Dickinson's "Exultation Is the Going" in 2009, shortly after the death of my mother, who like her brother weeks later, died within a stone's throw of Nantucket Sound. I felt the poem was a gift from her—a message across time and space to remember that the sea still holds her spirit and that sailing across the ocean is perhaps the best way I'll ever find to experience eternity.

Exultation is the going

Of an inland soul to sea,

Past the houses—past the headlands—

Into deep Eternity—

Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the first league out from land?

—Emily Dickinson

Timothy Shriver is the chief executive officer of Special Olympics.

Next: How Sharon Olds came to terms with the end of her marriage

Photo: Courtesy Sharon Olds

Sharon Olds cuts the ties that bind.

Maybe 12 or 13 years ago, I came to the end of my marriage, which lasted 32 years—and it was a great shock. It was so unexpected that my sense of myself really got shaken. Not myself as a mother or as a teacher or a friend, but just me, whoever I was when I was alone. And suddenly I was alone a lot. Lucille Clifton's "won't you celebrate with me" helped, especially the last two lines, "something has tried to kill me / and has failed," even though I had experienced nothing like what she had, coming of age in this country when she did. Still, the poem just sounded so true, and it was encouraging. It's good not to let your mind go slithering down into the bad things it likes to get moody about. It has to do with my belief in doing everything I can to help myself remember all that each one of us can do for our own personal calm and happiness, and for the people directly around us—and even for the world.

won't you celebrate with me

won't you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

—Lucille Clifton

Sharon Olds has written 11 poetry books.

Next: The poem David Rakoff knows by heart

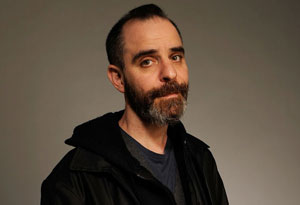

Photo: Getty Images

David Rakoff comes through with a little help from Elizabeth Bishop.

I have been using Elizabeth Bishop's "Letter to N.Y." for the last few years just as reliantly and regularly as I take aspirin for headaches. Every few weeks or so, I have an MRI to check on a tumor that has tenaciously nestled itself behind my collarbone. The hope of each scan is that the chemotherapy I'm regularly receiving is working and the mass is getting smaller and my brilliant surgeon will soon be able to work her magic without having to amputate my left arm.

"Letter to N.Y." is perfect for the coffin (that is what the MRI is, make no mistake). To the adept claustrophobe, all those assurances that the machine is a brilliant, lifesaving diagnostic marvel are nothing but noise when confronted with a ceiling scarcely four inches from one's face. To open your eyes, I hardly need advise you, would be a grievous mistake.

In addition, it is vital not to start reciting too early. To do so would rob the poem of its calming, analgesic power. It is not until I have undressed and divested my body of all metal and put on my hospital gown, not until the tranquilizer has started to kick in and my breathing has become less ragged and more cello-like and I am on the slab being scanned, that I begin my incantation.

To be sure, the content of Bishop's lines is secondary to the busywork of recitation. It is in the task where the distracting, meditative cure lies. But then, from out of the darkness come the barely-seen flashes of meaning, like the nighttime trees of Central Park whizzing past a taxi window, or the half-heard innuendo struggling through the muzzy din of some after-hours joint.

Lying on the table, it can sometimes feel like I've been in treatment longer than I've been alive; that my world has contracted and been bricked over and this is who I am and will only ever be. There is solace in the poem's portrait of New York City, my home for close to three decades. It's a New York not just of my healthier but of my younger self. And it's nice to think of it all still being there, waiting for me, just as soon as I get up and walk out of this room.

Letter to N.Y. (for Louise Craine)

In your next letter I wish you'd say

where you are going and what you are doing;

how are the plays, and after the plays

what other pleasures you're pursuing:

taking cabs in the middle of the night,

driving as if to save your soul

where the road goes round and round the park

and the meter glares like a moral owl,

and the trees look so queer and green

standing alone in big black caves

and suddenly you're in a different place

where everything seems to happen in waves,

and most of the jokes you just can't catch,

like dirty words rubbed off a slate,

and the songs are loud but somehow dim

and it gets so terribly late,

and coming out of the brownstone house

to the gray sidewalk, the watered street,

one side of the buildings rises with the sun

like a glistening field of wheat.

—Wheat, not oats, dear. I'm afraid

if it's wheat it's none of your sowing,

nevertheless I'd like to know

what you are doing and where you are going.

—Elizabeth Bishop

David Rakoff is the author of three essay collections, including, most recently Half Empty (Doubleday).

Keep Reading: David Rakoff on loving other people's dogs

Next: Kim Rosen describes losing her life savings

Photo: Karen Moskowitz

Kim Rosen gains more than she lost.

In October 2008, I invested all my savings in a small, local fund. Two months later, the friend who had told me about the fund left me a message: "Bernard Madoff was arrested today. The fund was a fraud. We've lost everything."

I stood there, not breathing, clutching the phone as the voice-mail lady repeated: "To replay this message, press one." Then, out of nowhere, I heard these words in my mind: Before you know what kindness really is / you must lose things....

Though I'd heard Naomi Shihab Nye's "Kindness" before, I had never really been drawn to the poem. And I certainly didn't know it was in my memory. Nevertheless, the next lines unfurled in my mind like a karaoke crib sheet.

Of course, there were suddenly a thousand things I needed to do: contact my lawyer and my accountant, figure out how to pay the bills I'd accrued when I thought I had money—not to mention rent, food, and health insurance. But all I could think to do was google "Kindness." That poem became the prayer that carried me in the days and months that followed.

Kindness

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness,

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to mail letters and purchase bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

—Naomi Shihab Nye

Kim Rosen is the author of Saved by a Poem (Hay House) and the cocreator of four albums of music and poetry.

More Powerful Poetry

"Sara in Her Father's Arms" by George Oppen. From New Collected Poems, ©1962 by George Oppen. Reprinted by permission of New Direction Publishing Corp.