Photo: Courtesy of Maggie Shipstead

As a child, I liked to browse my mother's bookshelves in hopes of finding something I wasn't supposed to see. When I was 6, poking through her collection of ballet books, I came across a glossy hardback with the promising title Private View, but it contained mostly chaste black-and-white photos of dancers working in the studio or waiting offstage in the shadowy wings. One of the dancers did catch my eye, though. He had an intriguing, contradictory face: melancholy but impish, boyish but lined, sometimes playful, other times stern. Even when he smiled, he looked guarded, a little mysterious. I wanted to know who he was.

"That's Mikhail Baryshnikov," my mother said when I interrupted her to show her the book. She was a professor of child development, always elbow-deep in students' papers.

"Who?" I liked the strange sound of his name: the hard k's, the brush of the sh. "Who's he?"

She gave the only possible answer. "He's a dancer. One of the best ever."

Taking the book, she swiveled away and paged through it, absorbed in the images. Then she turned back to show me a photo of Baryshnikov dancing. He wore loose black pants and a sweater tied around his shoulders and was midmovement, leaning to one side, arms low, gazing intently into the mirror. "He's so focused, yet so relaxed," she said. "See? Even something simple like this he does with such precision that it becomes beautiful."

For the first time in what would become a long history of looking at dancers with my mother, I experienced the pleasure of recognizing what she meant: I saw how the tension between Baryshnikov's apparent ease and his consummate control made the photo come alive. And then I recognized something else: Mom had a whole shelf of ballet books because she cared about ballet. She was the center of my universe, but in all my orbiting of her, my basking in her affection and attention, I'd never quite considered that she wasn't entirely consumed by me. The idea was alarming, but also a little thrilling.

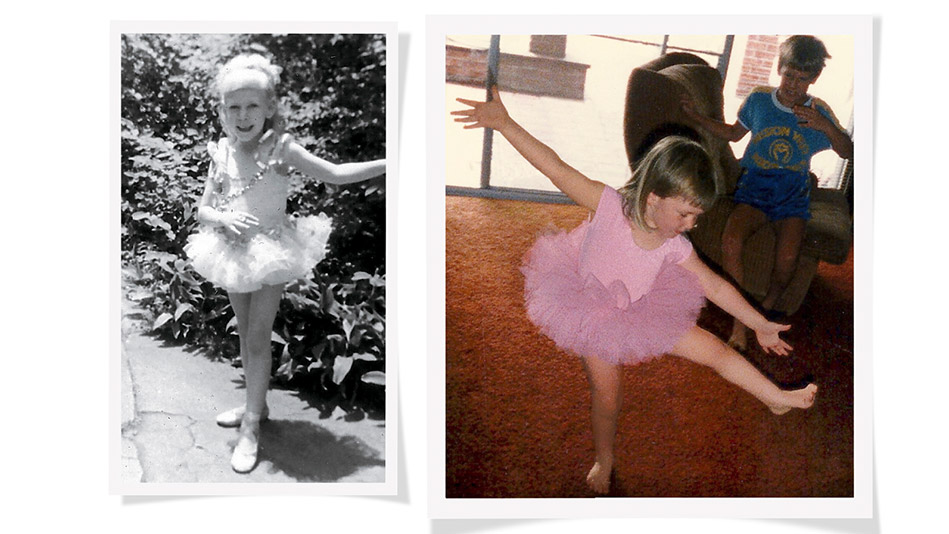

My own ballet career was already over. After a year of kindergarten classes, it was obvious to everyone, including me, that I had zero talent. Mom didn't mind when I told her I wanted to quit. More than a dancing daughter, what she really wanted was someone who'd go to the ballet with her; my dad, in the grand tradition of dads, was not interested. Hopeful that I could be molded into a fan, she bought us tickets to the dance season at the Orange County Performing Arts Center, near where we lived in California. Our seats were orchestra, row F, dead center. "I need a good view of their feet," Mom said. Sometimes during a performance she would murmur with amazement, and I would study the stage, trying to see what she saw.

She'd witnessed all the greats. "Oh, yeah, I saw Nureyev in '69," she'd drop with the air of someone talking about Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock. "Easter Sunday in Amsterdam. Giselle. People threw tulips on the stage." As a teenager traveling in Europe with her family, she went alone to London's Covent Garden before dawn and waited for hours to buy a standing-room ticket to see Margot Fonteyn dance Swan Lake.

In the early '70s, my newlywed parents had moved to Princeton for my dad's master's degree. Her own graduate studies postponed, bored at a desk job, Mom, who hadn't danced since childhood, joined a ballet class of local teenagers. When I think about this now, it seems like the height of daring. Taking on a notoriously difficult art as an adult when even proficiency is a pipe dream? Sharing a barre with a gaggle of bun-headed Jersey girls? But the hopeless audacity exhilarated her. She was a minister's daughter, a middle child who'd worked summer jobs at psychiatric hospitals and inner-city preschools and who, for her 15th birthday, asked to be taken to Montgomery, Alabama, to march with Martin Luther King Jr.

Ballet was a respite from responsibility, something just for her. Its Zen-like focus on the body was an indulgence. She bought records of piano accompaniment and did extra work at a makeshift barre at home. She fought her way en pointe. Once, she got out of bed and fell to the floor, her legs exhausted, and was perversely pleased to have to call in sick. Another time, two young men from her office came to watch her class and, presumably, to ogle her in her leotard, and she took a guilty pride in showing off her lean, strong body. But after two years, my parents moved again, and Mom's dancing days ended.

"That's Mikhail Baryshnikov," my mother said when I interrupted her to show her the book. She was a professor of child development, always elbow-deep in students' papers.

"Who?" I liked the strange sound of his name: the hard k's, the brush of the sh. "Who's he?"

She gave the only possible answer. "He's a dancer. One of the best ever."

Taking the book, she swiveled away and paged through it, absorbed in the images. Then she turned back to show me a photo of Baryshnikov dancing. He wore loose black pants and a sweater tied around his shoulders and was midmovement, leaning to one side, arms low, gazing intently into the mirror. "He's so focused, yet so relaxed," she said. "See? Even something simple like this he does with such precision that it becomes beautiful."

For the first time in what would become a long history of looking at dancers with my mother, I experienced the pleasure of recognizing what she meant: I saw how the tension between Baryshnikov's apparent ease and his consummate control made the photo come alive. And then I recognized something else: Mom had a whole shelf of ballet books because she cared about ballet. She was the center of my universe, but in all my orbiting of her, my basking in her affection and attention, I'd never quite considered that she wasn't entirely consumed by me. The idea was alarming, but also a little thrilling.

My own ballet career was already over. After a year of kindergarten classes, it was obvious to everyone, including me, that I had zero talent. Mom didn't mind when I told her I wanted to quit. More than a dancing daughter, what she really wanted was someone who'd go to the ballet with her; my dad, in the grand tradition of dads, was not interested. Hopeful that I could be molded into a fan, she bought us tickets to the dance season at the Orange County Performing Arts Center, near where we lived in California. Our seats were orchestra, row F, dead center. "I need a good view of their feet," Mom said. Sometimes during a performance she would murmur with amazement, and I would study the stage, trying to see what she saw.

She'd witnessed all the greats. "Oh, yeah, I saw Nureyev in '69," she'd drop with the air of someone talking about Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock. "Easter Sunday in Amsterdam. Giselle. People threw tulips on the stage." As a teenager traveling in Europe with her family, she went alone to London's Covent Garden before dawn and waited for hours to buy a standing-room ticket to see Margot Fonteyn dance Swan Lake.

In the early '70s, my newlywed parents had moved to Princeton for my dad's master's degree. Her own graduate studies postponed, bored at a desk job, Mom, who hadn't danced since childhood, joined a ballet class of local teenagers. When I think about this now, it seems like the height of daring. Taking on a notoriously difficult art as an adult when even proficiency is a pipe dream? Sharing a barre with a gaggle of bun-headed Jersey girls? But the hopeless audacity exhilarated her. She was a minister's daughter, a middle child who'd worked summer jobs at psychiatric hospitals and inner-city preschools and who, for her 15th birthday, asked to be taken to Montgomery, Alabama, to march with Martin Luther King Jr.

Ballet was a respite from responsibility, something just for her. Its Zen-like focus on the body was an indulgence. She bought records of piano accompaniment and did extra work at a makeshift barre at home. She fought her way en pointe. Once, she got out of bed and fell to the floor, her legs exhausted, and was perversely pleased to have to call in sick. Another time, two young men from her office came to watch her class and, presumably, to ogle her in her leotard, and she took a guilty pride in showing off her lean, strong body. But after two years, my parents moved again, and Mom's dancing days ended.

Photo: Courtesy of Maggie Shipstead

In 1993, when I was 10, Baryshnikov came to Orange County with the White Oak Dance Project. By then, I fancied myself something of a ballet expert. I was a child who feared and disliked new things, and ballet appealed to my natural severity and conservatism. Baryshnikov danced a Twyla Tharp solo that slyly mocked the roles of his youth: the prince in Swan Lake and the count in Giselle, the slave boy in Le Corsaire. At one point, rolling his eyes, he fluttered his hands behind his back like wings. Everybody laughed. I nudged Mom. "What's funny?"

She whispered, "He's making fun of the big classical roles."

I sat back, offended. Those roles were my favorites.

Afterward, in the car, I said I didn't know why anyone would prefer modern dance to ballet. There were no pretty sets or costumes, no story. Mom listened, and then she explained how Baryshnikov had left—fled—his home country because he wanted artistic freedom. He had risked and sacrificed so much, she said, for a life where he could make fun of Giselle.

Ballet, I began to see, could be about more than watching feet.

Every so often I would steal into Mom's closet to try on her old pointe shoes, going up on my toes while clinging to a doorframe. She kept them on the highest shelf, in a Capezio box stacked on a Bruno Magli box that held an impossibly spindly pair of pink heels. I tried those on, too, marveling at how uncomfortable and perilous both pairs seemed, how alien they were from Mom's preferred felt clogs. These boxes held bits of the past, accessories for a graceful, nimble girl who danced on her toes and pranced in stilettos, a youthful stranger who still sometimes surfaced unexpectedly. In junior high, filling out a homework questionnaire about how well I knew my family, having aced my father's birthplace and grandmothers' maiden names, I read aloud the question, "Can your mother stand on her head?" "No," I scoffed, writing before she could answer. Without a word, she walked into the living room, planted her head on the carpet, and effortlessly swung her socked feet up to point at the ceiling. The dogs milled around her, puzzled. I applauded in astonished delight.

By the time we saw Baryshnikov again, I was 14 and had outgrown my mother's shoes. This time, he performed HeartBeat: mb, a piece accompanied by his own heartbeat as transmitted and amplified by sensors on his chest. He drove the beat up, let it fall. The dance was about mortality and aging, a dancer's intimate, collaborative, sometimes antagonistic relationship with his body. Inevitably, our bodies disappoint and betray us, the dance said, but how glorious to have a body in the first place, even just for a while.

It was 1998, and Mom and I were about to visit St. Petersburg, formerly Leningrad, the city where Baryshnikov became a star and where he has never returned since his defection. As a child, I developed a fascination with the Cold War that manifested in book reports on fat spy thrillers and expanded to encompass Russian history. That summer the remains of Tsar Nicholas II and his murdered family and servants, having languished in Siberia for almost 80 years, were being reinterred in St. Petersburg. I decided I had to witness this strange event (a cortege of speeding black minivans; Boris Yeltsin waving from a limo; clanging church bells), and after a protracted campaign, I got Mom to agree to take me.

The trip daunted us both. We were sisters in timidity: afraid of the subway, shy about the language barrier, skittish about the city's subterranean, curtained restaurants. But aware that this was all my idea, I rallied. I took charge of the foldable map. I puzzled out the Cyrillic street signs. I took my turn negotiating admission to churches in phrase-book Russian. That great, decisive separation—college—had begun to loom large between us, and I was beset by conflicting desires: to cling to Mom and also to protect myself by pushing her away. I marched impatiently down the street, pretending at independence, but as soon as something confused or startled me, I'd hide behind her like a lost lamb.

One of her conditions for the trip was to see the Mariinsky Ballet, formerly the Kirov, in its namesake theater. We saw La Sylphide. It was immediately apparent that the company hadn't yet recovered from its loss of Soviet funding or from the flight of dancers seeking better pay in the West. Cruise ship tour groups took flash photos. The imperial box stood empty. We did not have a good view of the feet. Afterward, at dinner in our hotel, Mom said, "I wouldn't bring back the old system, but I'm a little sad." I was taken aback by how sad I was, too. I'd barely noticed it happening, but over the years, she'd taught me enough about ballet that I didn't need her to tell me what was good anymore, when to be amazed or disappointed. I'd always wanted to see ballet as she saw it, to connect with it as she did, and finally, sitting in that creaky Russian theater, I had. We had become, in a small way, equals.

She whispered, "He's making fun of the big classical roles."

I sat back, offended. Those roles were my favorites.

Afterward, in the car, I said I didn't know why anyone would prefer modern dance to ballet. There were no pretty sets or costumes, no story. Mom listened, and then she explained how Baryshnikov had left—fled—his home country because he wanted artistic freedom. He had risked and sacrificed so much, she said, for a life where he could make fun of Giselle.

Ballet, I began to see, could be about more than watching feet.

Every so often I would steal into Mom's closet to try on her old pointe shoes, going up on my toes while clinging to a doorframe. She kept them on the highest shelf, in a Capezio box stacked on a Bruno Magli box that held an impossibly spindly pair of pink heels. I tried those on, too, marveling at how uncomfortable and perilous both pairs seemed, how alien they were from Mom's preferred felt clogs. These boxes held bits of the past, accessories for a graceful, nimble girl who danced on her toes and pranced in stilettos, a youthful stranger who still sometimes surfaced unexpectedly. In junior high, filling out a homework questionnaire about how well I knew my family, having aced my father's birthplace and grandmothers' maiden names, I read aloud the question, "Can your mother stand on her head?" "No," I scoffed, writing before she could answer. Without a word, she walked into the living room, planted her head on the carpet, and effortlessly swung her socked feet up to point at the ceiling. The dogs milled around her, puzzled. I applauded in astonished delight.

By the time we saw Baryshnikov again, I was 14 and had outgrown my mother's shoes. This time, he performed HeartBeat: mb, a piece accompanied by his own heartbeat as transmitted and amplified by sensors on his chest. He drove the beat up, let it fall. The dance was about mortality and aging, a dancer's intimate, collaborative, sometimes antagonistic relationship with his body. Inevitably, our bodies disappoint and betray us, the dance said, but how glorious to have a body in the first place, even just for a while.

It was 1998, and Mom and I were about to visit St. Petersburg, formerly Leningrad, the city where Baryshnikov became a star and where he has never returned since his defection. As a child, I developed a fascination with the Cold War that manifested in book reports on fat spy thrillers and expanded to encompass Russian history. That summer the remains of Tsar Nicholas II and his murdered family and servants, having languished in Siberia for almost 80 years, were being reinterred in St. Petersburg. I decided I had to witness this strange event (a cortege of speeding black minivans; Boris Yeltsin waving from a limo; clanging church bells), and after a protracted campaign, I got Mom to agree to take me.

The trip daunted us both. We were sisters in timidity: afraid of the subway, shy about the language barrier, skittish about the city's subterranean, curtained restaurants. But aware that this was all my idea, I rallied. I took charge of the foldable map. I puzzled out the Cyrillic street signs. I took my turn negotiating admission to churches in phrase-book Russian. That great, decisive separation—college—had begun to loom large between us, and I was beset by conflicting desires: to cling to Mom and also to protect myself by pushing her away. I marched impatiently down the street, pretending at independence, but as soon as something confused or startled me, I'd hide behind her like a lost lamb.

One of her conditions for the trip was to see the Mariinsky Ballet, formerly the Kirov, in its namesake theater. We saw La Sylphide. It was immediately apparent that the company hadn't yet recovered from its loss of Soviet funding or from the flight of dancers seeking better pay in the West. Cruise ship tour groups took flash photos. The imperial box stood empty. We did not have a good view of the feet. Afterward, at dinner in our hotel, Mom said, "I wouldn't bring back the old system, but I'm a little sad." I was taken aback by how sad I was, too. I'd barely noticed it happening, but over the years, she'd taught me enough about ballet that I didn't need her to tell me what was good anymore, when to be amazed or disappointed. I'd always wanted to see ballet as she saw it, to connect with it as she did, and finally, sitting in that creaky Russian theater, I had. We had become, in a small way, equals.

Photo: Courtesy of Maggie Shipstead

These days I go to the ballet whenever I can, but the experience still feels incomplete without my mother. After seeing La Bayadère in Paris, where I spent a winter, I called home as I left the theater, needing to tell her about the exquisiteness of the dancers, about the Frenchman beside me who cried through the first act. I wanted her to have seen it. Or maybe I wanted the impossible: to be a grown woman walking alone on a frosty Parisian sidewalk, but also to have my mother with me always.

Recently, one afternoon at my parents' house in San Diego, I parked myself on the couch. Mom was busy in her sewing room, but I wanted her to come sit with me. She would have if I'd asked, but only to be nice, to please me. At this point, I preferred her to please herself but wasn't above trying to lure her. On Apple TV, I typed "Baryshnikov" in the YouTube search box and chose a clip of him dancing competitively with Gregory Hines in the defector drama White Nights. Before it was over, Mom had settled next to me. I chose another: teenage Baryshnikov in class at the Vaganova ballet school in Leningrad. The resolution wasn't great; the old footage flickered. Still, we let it play to the end. We were watching an astonishing artist. We were witnessing the passage of time.

Maggie Shipstead recently published her second novel, Astonish Me

Recently, one afternoon at my parents' house in San Diego, I parked myself on the couch. Mom was busy in her sewing room, but I wanted her to come sit with me. She would have if I'd asked, but only to be nice, to please me. At this point, I preferred her to please herself but wasn't above trying to lure her. On Apple TV, I typed "Baryshnikov" in the YouTube search box and chose a clip of him dancing competitively with Gregory Hines in the defector drama White Nights. Before it was over, Mom had settled next to me. I chose another: teenage Baryshnikov in class at the Vaganova ballet school in Leningrad. The resolution wasn't great; the old footage flickered. Still, we let it play to the end. We were watching an astonishing artist. We were witnessing the passage of time.

Maggie Shipstead recently published her second novel, Astonish Me