9 Lessons from the Fictional Women We've Always Wanted to Be

By Amy Shearn

Ask any reader her favorite literary heroine, and she'll stare off into the distance, smiling, then immediately start reeling off names and anecdotes: Katniss! Elizabeth Bennett! As Anne Patchett put it, "Reading fiction is important. It is a vital means of imagining a life other than our own, which in turn makes us more empathetic beings." Here's what 9 of our favorite fictional women have taught us about our own, very real lives.

Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro

Vintage

Go for the Deferral

Kathy, the stoic narrator in Kazuo Ishiguro's novel Never Let Me Go, has always felt a connection with her boarding school classmate Tommy. (Warning: spoilers ahead.) While the two have some extraordinary circumstances with which to contend—they happen to be clones, created so that their organs may be harvested—their romance operates under the usual rules. So when Kathy's best friend stakes her claim on Tommy, Kathy walks away. By the time Kathy and Tommy find one each other again, he's on his deathbed. In their world, rumor has it that clones may receive a deferral that will spare their life, if they can prove they are really in love...and thus human. Sure, love saves us all, but in this instance, love would really, really save Tommy, who is about to have all of his organs removed. As Kathy puts it, "There was something in Tommy's manner that was tinged with sadness, that seemed to say: 'Yes, we're doing this now and I'm glad we're doing it now. But what a pity we left it so late.''' He may be correct, but what we love about Kathy is that even in an existence defined by disappointment, when she should know better, she allows herself to love generously, as if that deferral were still possible, long after she finds out that it is not. We should all love like it will save us from being sliced open. You know, so to speak.Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro

Vintage

Remember the Greek Goddess in You

Ever wonder how you'd survive if things got bad? Really bad? Like if you were 15, pregnant, poor, your mother was dead, your father was an alcoholic and you were living in the path of Hurricane Katrina? Esch, in Jesmyn Ward's National Book Award–winning Salvage the Bones, summons her inner strength in part by channeling her favorite nymphs and goddesses from Greek myths. At a chaotic store where panicked people are stocking up for the coming storm, Esch says, "I am small, dark: invisible. I could be Eurydice walking through the underworld to dissolve, unseen." When her boyfriend rejects her, she says, "In every one of the Greeks' mythology tales, there is this: a man chasing a woman, or a woman chasing a man." Our struggles are never just our own; even 15-year-old Esch knows there is a larger story somewhere that can help us understand our own lives. As things get worse and worse, as they do in these sorts of stories, she not only finds that she has the strength to survive it all but also reminds us that even when we don't find love or support from the people from whom we want to receive it, that doesn't mean others aren't offering it.

Salvage the Bones

Jesmyn Ward

Bloomsbury USA

Salvage the Bones

Jesmyn Ward

Bloomsbury USA

Even the Insufferably Perfect Work At It

We know, we know: Jo, with all her rough-and-tumble imperfections, is everyone's favorite little woman. But perhaps the true heroine of Louisa May Alcott's classic is the matriarch of the March family, Marmee, who raises her four girls alone while her husband's at war and never seems to so much as ruffle a feather. Meanwhile, some of us (not naming any names) lose our patience completely by 8:00 a.m. at the third "Oops, I dropped my dolly in the toilet!" Like Jo, we can all look to Marmee to answer the question: "How did you learn to keep still?" The sage Marmee’s answer: "I am not patient by nature...I must try to practice all the virtues I would have my little girls possess." Good to know that even literature's most perfect mother has to work at it.

Little Women

Louisa May Alcott

Signet Classics

Little Women

Louisa May Alcott

Signet Classics

Focus on Your Skills, Not Your Scars

That glass ceiling looks like a skylight when you consider the forces a working woman in early 19th-century Japan had to contend with. Orito Aibagawa is the facially scarred Japanese midwife-in-training from David Mitchell's The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet who is studying medicine under a Dutch doctor, a privilege unheard of for a woman in her time and place and earned only by delivering a powerful magistrate's seemingly stillborn son. She goes on to be kidnapped by monks and detained in a nunnery, from where she escapes, managing in the process to blow the lid off a despicable, far-reaching scandal victimizing women and babies—in true Raiders of the Lost Ark fashion, no less. Above all, Orito believes that her talents for medicine and midwifery must be used to save lives and that she can't be distracted by little things like her own troubles or even the suitors vying for her affections. "Self-pity," she reminds herself, "is a noose dangling from a rafter." Scarred, underestimated and kidnapped by evil monks—hey, we all have our trials—Orito survives it all in total superhero style.

The Thousand Autums of Jacob de Zoet

David Mitchell

Random House

The Thousand Autums of Jacob de Zoet

David Mitchell

Random House

Go to the Island

Juliet Ashton, in the epistolary novel The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, is a writer living in post–World War II London who has begun to experience some degree of success and feels the pressure to make her next book a real winner. But Juliet finds herself stuck on her current project, along with just about every aspect of her life. Then a letter left in an old novel draws her into an exchange with Dawsey Adams, a bookish farmer on the remote island of Guernsey. Dawsey begins to reveal to Juliet the story of how Guernsey survived German occupation, and soon Juliet is corresponding with all the members of this close-knit community. Not only does she decide to tell their story—"Every biography should be written within a generation of its subject's life, while he or she is still in living memory," she explains—but she also allows herself to fall in love with these people (and, ahem, one in particular), despite the fact they are so unlike her pals in the big city. In fact, Juliet follows her fascination to the point of entering into their story. She travels to the island of Guernesy, and by the end she has married one of her pen pals and adopted another (and, you guessed it, found a subject for her new book). Imagine it: researching a place, finding it interesting, connecting with the people and then, not writing about it or looking at photos online or watching a movie about it, but plunging ahead, full-bore, into a new life.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society

Mary Ann Schaffer and Annie Barrows

Dial Press Trade Paperback

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society

Mary Ann Schaffer and Annie Barrows

Dial Press Trade Paperback

Marry the Broke Guy

George Eliot's sprawling novel Middlemarch tells, among its many narrative strands, the story of Dorothea Brooke, an idealistic woman who makes the mistake most likely to ruin a life: She marries the wrong man. (Warning: spoilers ahead.) Reverend Edward Casaubon is ambitious and scholarly—and, Dorothea soon learns, cold, distant and self-centered. She had hoped to help him finish his life's work, an important book called The Key to All Mythologies, only to realize he has no interest in her thoughts or even really in the work itself. Conveniently, he dies. Inconveniently, he writes in his will that if Dorothea marries his estranged relation Will Ladislaw, she can't inherit Casaubon's money and property. Conveniently, Dorothea finds the man who actually is right for her, who respects her mind and loves her for who she is. Inconveniently, it happens to be this very same Will Ladislaw. Even more inconveniently, he has no income or land of his own. Here was a society that didn't encourage independence or self-awareness in women at all, and here was a woman who saw the error in her—perfectly respectable, but not right for her—life choices and figured out how to be happy in spite of resistance. We all have our Dorothea-like notions about what we should do, about who we should be. How much courage would it take to actualize what is true about ourselves?

Middlemarch

George Eliot

Penguin Classics

Middlemarch

George Eliot

Penguin Classics

When the Humans Let You Down, Talk to the Dolls

When we meet 12-year-old Maggie Turner, the heroine of Sylvia Cassedy's underrated young-adult novel Behind the Attic Wall, she's scowling, dressed in brown and almost immediately vomits. As a kid reading this book, I loved her. She's the anti-Alice, the un-Annie—a grouchy mess of an orphan who seems to resist all friendly advances, all inklings of pleasantness. After getting sent to live with her stern maiden aunts in a creepy mansion, she doesn't want to find a world of wonder, she just wants to break stuff. Then she discovers a pair of dolls in the attic who talk to her. This is a child who has never had a single friend, mind you, and it is truly with a joyful excitement that you watch her start to take care of the dolls, to join them in their never-ending tea party, to help them take some air in the garden (a strip of flowered wallpaper). Maggie's self-loathing is so complete that she hates her own name and finds even her knees to be ugly; accepting that she might be capable of loving, worthy of being loved, comes as a complete surprise to her. But guess what? After practicing on the dolls, she finds herself ready to love actual humans too, and—to her, this is the biggest surprise of all—ready to be loved in return.

Behind the Attic Wall

Sylvia Cassedy

HarperCollins

Behind the Attic Wall

Sylvia Cassedy

HarperCollins

Pay Attention to the Man Who Believes He's Married to a Pigeon

The impoverished old man who lives in room 3327 of the New Yorker Hotel is obsessed with pigeons—one in particular, which he calls his wife. He claims that he has communicated with Mars, created a death ray, and invented electricity, radio and remote control. He thinks that telephones will some day not need wires. Clearly, he's a kook. But Louisa Dewell, the hotel chambermaid who narrates Samantha Hunt's beautiful historical novel The Invention of Everything Else, befriends this lonely man. Turns out, he's Nikola Tesla, who actually did pioneer alternating-current electricity and was responsible for countless other inventions, but now finds himself snubbed and forgotten. Not only does this friendship infuse variety into Louisa's mind-numbing job, but it offers her insight into the life of her own father and, just maybe, the chance to reconnect with her long-dead mother. Too often we look for new friends who are, well, pretty much just like us. Louisa's story shows that by opening up, by offering a lonely person some attention, by learning to listen, to really listen, we may stumble upon a friendship unlike any other.

The Invention of Everything Else

Samantha Hunt

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

The Invention of Everything Else

Samantha Hunt

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Build Your Own Bottle-Cap Universe

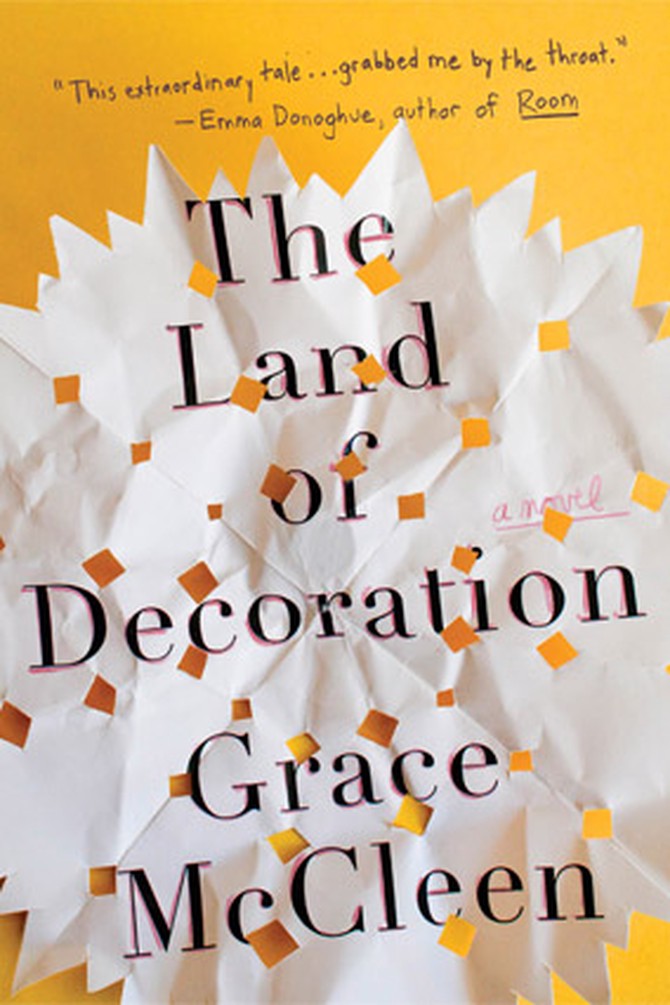

The 10-year-old narrator of The Land of Decoration has the total underdog package: dead mother, weird father, strange religion, school bullies. But Judith McPherson has found a way to make sense of life: a diorama of the universe that she has built in her room, planets, oceans, factories and all. When everything seems to be against you, you could retreat in anger or fear. Or you could collect bottle caps and orange peels and make a new world of your own.

The Land of Decoration

Grace McCleen

Henry Holt and Company

Next: The mysteries every thinking woman should read

The Land of Decoration

Grace McCleen

Henry Holt and Company

Next: The mysteries every thinking woman should read

Published 04/24/2012