You're certain you know what your problem is. Fabulous, says Martha Beck—unless it's distracting you from an even more alarming issue. O's life coach goes deep.

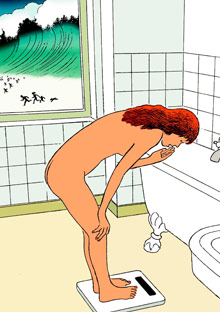

Illustration: Guy Billout

Tricia was depressed. That was her only problem. Although her life had all the right ingredients—successful husband, decent job, close-knit family—Tricia felt so low that she sometimes threatened suicide. When her therapist invited her husband, parents, and sister for a family session, a discussion of Tricia's "spells" devolved into a verbal brawl. Her parents, who'd been drinking, bickered about their mutual infidelity. Her sister wept like a fire hydrant. Tricia's husband shouted that they were ruining his life. In short, Tricia's depression was not her only problem. Instead, it was what I call her designated issue.

Tricia herself would be recognized by systems therapists as a "designated patient," the one person in a family or group who's singled out as sick or abnormal, allowing everyone else to feel healthy by comparison. A designated patient "carries" the group's dysfunction. A designated issue performs the same service for an individual, dominating our psyches so that other troubles can go unnoticed.

You probably have a designated issue. Almost all my clients do. (And I myself have had several.) Annabeth obsesses endlessly about her weight (once upon a time, I did, too). Libbie pines for a soul mate (been there, done that). Loving mother Kristen worries constantly about her children's safety (I'm three for three). As a designated-issue connoisseur, I know what these ladies think: If they could only fix this problem, life would be a bowl of pitted Maraschino cherries. But their problems stubbornly resist fixing. Why? Because designated issues aren't just problems; they're also solutions. Like toxic-waste receptacles, they serve the useful function of containing some nasty, scary material. Your so-called worst problem may be sparing you even greater distress. You can thank it for that. And then you can get rid of it—though not quite in the way you might expect.

Life, as psychologist William James famously said, is "one great blooming, buzzing confusion." We stumble through it, suffering many woes and imagining infinite others, with all the confident self-assurance of squirrels trying to teach dog obedience classes. To calm ourselves, we may pickle our fears in alcohol, scorch them with nicotine, haul them to yoga, therapy, and church. Focusing on one mildly disturbing, semi-controllable issue allows the mind to stuff much greater terrors in relatively tidy packages. Yes, Earth's climate is changing, bird flu seems imminent, wars and genocides rage—and wouldn't you rather think about your cholesterol level?

Me, too.

This is the real reason Tricia developed the moody blues. Her depression let everyone in her family worry just enough to avoid facing 50-some years of truly spectacular dysfunction. When Tricia's therapist threw a wrench into this system, his designated patient's designated issue coughed up secrets everyone had been hiding. Here are some more true stories:

"I'm sick of thinking about my weight," moaned chubby Annabeth.

"Okay," I replied, "let's talk about your marriage."

"Sure. Just a second," said Annabeth. She yanked a king-size candy bar from her purse and attacked it like a starving lumberjack—something she did whenever the topic of marriage arose.

Like Annabeth's weight problems, Libbie's quest for the perfect relationship was a 24/7 occupation. I thought it might be useful to discuss her avocation of selling marijuana, but getting her off the topic of romance was like taking beefsteak from a pit bull. If she'd been any less stoned, I might've lost a finger.

Kristen's crisis hit when she bounced a check to the private investigator she'd hired to make sure her grown children were living safely while at college. The kids were fine, but Kristen's finances were in shambles—a problem she'd pushed aside to focus on protecting her young.

Tricia herself would be recognized by systems therapists as a "designated patient," the one person in a family or group who's singled out as sick or abnormal, allowing everyone else to feel healthy by comparison. A designated patient "carries" the group's dysfunction. A designated issue performs the same service for an individual, dominating our psyches so that other troubles can go unnoticed.

You probably have a designated issue. Almost all my clients do. (And I myself have had several.) Annabeth obsesses endlessly about her weight (once upon a time, I did, too). Libbie pines for a soul mate (been there, done that). Loving mother Kristen worries constantly about her children's safety (I'm three for three). As a designated-issue connoisseur, I know what these ladies think: If they could only fix this problem, life would be a bowl of pitted Maraschino cherries. But their problems stubbornly resist fixing. Why? Because designated issues aren't just problems; they're also solutions. Like toxic-waste receptacles, they serve the useful function of containing some nasty, scary material. Your so-called worst problem may be sparing you even greater distress. You can thank it for that. And then you can get rid of it—though not quite in the way you might expect.

Life, as psychologist William James famously said, is "one great blooming, buzzing confusion." We stumble through it, suffering many woes and imagining infinite others, with all the confident self-assurance of squirrels trying to teach dog obedience classes. To calm ourselves, we may pickle our fears in alcohol, scorch them with nicotine, haul them to yoga, therapy, and church. Focusing on one mildly disturbing, semi-controllable issue allows the mind to stuff much greater terrors in relatively tidy packages. Yes, Earth's climate is changing, bird flu seems imminent, wars and genocides rage—and wouldn't you rather think about your cholesterol level?

Me, too.

This is the real reason Tricia developed the moody blues. Her depression let everyone in her family worry just enough to avoid facing 50-some years of truly spectacular dysfunction. When Tricia's therapist threw a wrench into this system, his designated patient's designated issue coughed up secrets everyone had been hiding. Here are some more true stories:

"I'm sick of thinking about my weight," moaned chubby Annabeth.

"Okay," I replied, "let's talk about your marriage."

"Sure. Just a second," said Annabeth. She yanked a king-size candy bar from her purse and attacked it like a starving lumberjack—something she did whenever the topic of marriage arose.

Like Annabeth's weight problems, Libbie's quest for the perfect relationship was a 24/7 occupation. I thought it might be useful to discuss her avocation of selling marijuana, but getting her off the topic of romance was like taking beefsteak from a pit bull. If she'd been any less stoned, I might've lost a finger.

Kristen's crisis hit when she bounced a check to the private investigator she'd hired to make sure her grown children were living safely while at college. The kids were fine, but Kristen's finances were in shambles—a problem she'd pushed aside to focus on protecting her young.

From the outside, it's obvious these women were using their "worst" problems as distractions from much worse ones. Yet each claimed, "If I could only fix this one thing, I'd be so happy!" I'll be the first to admit, designated issues are troubling. Tricia was depressed, Annabeth's weight threatened her health, Libbie's loneliness was undeniable, and Kristen's children (like all children) were genuinely vulnerable to life's dangers. But certain characteristics distinguish these issues from everyday problems. I've put together a quiz to help you tell the difference, and the following are also useful guidelines:

1. Designated issues command inordinate mindshare. I recently discovered ants in my guest bedroom—more of a scouting party than an infestation, but still. Ick. I swept them up, booked an eco-friendly exterminator, and stopped thinking about it. This is how we react to ordinary challenges: After taking reasonable action, we relax our attention.

If insect pests were my designated issue, the ants would have absorbed much more mental focus. I'd have called dozens of exterminators, stayed up late researching pesticides, filled my consciousness with anti-ant antics. If you ruminate this way about a single subject, despite the fact that your exertions aren't helping, you've probably got a designated issue on your hands—or, rather, on your mind. Consciously, you want more than anything to be rid of this dilemma. Subconsciously, you depend on it.

2. Designated issues dodge permanent solutions. When we solve a problem, things go according to plan. Designated issues, on the other hand, resist dozens, even hundreds of efforts that should rightfully demolish them. Annabeth's weight keeps popping back up, though she's lost it over and over. The issue isn't genetics; it's that Annabeth sabotages all her own weight loss strategies because her overeating helps her avoid noticing that she and her husband are miserable together.

3. Designated issues synchronize with seemingly unrelated events. When Tricia became depressed, her doctor prescribed a little something to cheer her up. But her mood fluctuated even on antidepressants. Tricia's therapist eventually noticed that Tricia's spells coincided with disagreements between her relatives. Each time the family brewed up a brouhaha, Tricia fell apart. This united the family as if she'd torched her house. Everyone forgot their differences and formed an emotional bucket line to "fix" her.

Similarly, Libbie's loneliness waxed and waned not according to her relationship status but to her marijuana supply (more weed = less loneliness). Spendaholic Kristen grew panicky about her kids right around tax time. My own designated issues spike in response to writing deadlines, which is why, at this moment, I am incredibly worried about my gums.

1. Designated issues command inordinate mindshare. I recently discovered ants in my guest bedroom—more of a scouting party than an infestation, but still. Ick. I swept them up, booked an eco-friendly exterminator, and stopped thinking about it. This is how we react to ordinary challenges: After taking reasonable action, we relax our attention.

If insect pests were my designated issue, the ants would have absorbed much more mental focus. I'd have called dozens of exterminators, stayed up late researching pesticides, filled my consciousness with anti-ant antics. If you ruminate this way about a single subject, despite the fact that your exertions aren't helping, you've probably got a designated issue on your hands—or, rather, on your mind. Consciously, you want more than anything to be rid of this dilemma. Subconsciously, you depend on it.

2. Designated issues dodge permanent solutions. When we solve a problem, things go according to plan. Designated issues, on the other hand, resist dozens, even hundreds of efforts that should rightfully demolish them. Annabeth's weight keeps popping back up, though she's lost it over and over. The issue isn't genetics; it's that Annabeth sabotages all her own weight loss strategies because her overeating helps her avoid noticing that she and her husband are miserable together.

3. Designated issues synchronize with seemingly unrelated events. When Tricia became depressed, her doctor prescribed a little something to cheer her up. But her mood fluctuated even on antidepressants. Tricia's therapist eventually noticed that Tricia's spells coincided with disagreements between her relatives. Each time the family brewed up a brouhaha, Tricia fell apart. This united the family as if she'd torched her house. Everyone forgot their differences and formed an emotional bucket line to "fix" her.

Similarly, Libbie's loneliness waxed and waned not according to her relationship status but to her marijuana supply (more weed = less loneliness). Spendaholic Kristen grew panicky about her kids right around tax time. My own designated issues spike in response to writing deadlines, which is why, at this moment, I am incredibly worried about my gums.

And you? If you have a persistent worry, notice correlations between it and unrelated activities. Does your grudge toward politicians become fury en route to your office? Do you schedule more plastic surgery whenever you think about decluttering your house? If so, you can stamp those preoccupations designated issues, and sincerely thank them for containing your other worries.

This gratitude for your most maddening chronic problem will likely arise spontaneously, but only after some heavy psychological lifting. Here's the basic process:

1. Sit down in a peaceful space, either alone or with someone who's willing to act as a friend and adviser.

2. Imagine as vividly as you can that your designated issue is gone. Vanished. Not even a memory. Doesn't that feel great?

3. Ask yourself, "Now that I've fixed that, what problems do I still have to face?" The answer will be sobering. Your unpaid rent, your cat's mange, your beloved aunt's dementia—all the unglamorous, frightening realities of your life will spill from the lead-lined box of your designated issue in a big, ungodly mess.

4. Pick one of these unpleasant problems, and take at least one step toward solving it. Negotiate with your landlord. Bring Snowball to the vet. Join a support group for people whose relatives have Alzheimer's.

5. After taking this one step, go right back to obsessing about your designated issue.

This last step may surprise you—isn't the goal to destroy the designated issue once and for all? Not necessarily. You need your obsession to hold your inner turmoil; otherwise, you wouldn't have created it.

Repeat the process outlined above, and you'll find your designated issue getting smaller, lighter, less compulsive. It's been years since I was driven by food obsession, but I still find it deeply soothing to write down everything I've eaten during the day. I used to think this process would help me control my weight, and thus my life. I no longer believe that, but its calming effect lingers. Calorie counting may seem like a strange response to, say, speeding tickets, but it works for me.

The process also helped Tricia: As she therapized about her nutty family, her depression eased, transmogrifying her designated issue from a torture chamber to a study. Annabeth faced her marital dissatisfaction, got divorced, and lost 50 pounds. Sadly, Libbie never dealt with her dealing; she still obsesses about Prince Charming. But Kristen's fear for her children abated as she learned money management. If you have a designated issue, addressing other problems will (eventually) make it dry up and blow away. In its place you'll find self-empowerment and gratitude—even, weirdly, gratitude that your brain has the capacity to create another designated issue, should the blooming, buzzing confusion of your life ever require one.

Martha Beck is the author of six books, including Steering by Starlight (Rodale).

More Advice From Martha Beck

This gratitude for your most maddening chronic problem will likely arise spontaneously, but only after some heavy psychological lifting. Here's the basic process:

1. Sit down in a peaceful space, either alone or with someone who's willing to act as a friend and adviser.

2. Imagine as vividly as you can that your designated issue is gone. Vanished. Not even a memory. Doesn't that feel great?

3. Ask yourself, "Now that I've fixed that, what problems do I still have to face?" The answer will be sobering. Your unpaid rent, your cat's mange, your beloved aunt's dementia—all the unglamorous, frightening realities of your life will spill from the lead-lined box of your designated issue in a big, ungodly mess.

4. Pick one of these unpleasant problems, and take at least one step toward solving it. Negotiate with your landlord. Bring Snowball to the vet. Join a support group for people whose relatives have Alzheimer's.

5. After taking this one step, go right back to obsessing about your designated issue.

This last step may surprise you—isn't the goal to destroy the designated issue once and for all? Not necessarily. You need your obsession to hold your inner turmoil; otherwise, you wouldn't have created it.

Repeat the process outlined above, and you'll find your designated issue getting smaller, lighter, less compulsive. It's been years since I was driven by food obsession, but I still find it deeply soothing to write down everything I've eaten during the day. I used to think this process would help me control my weight, and thus my life. I no longer believe that, but its calming effect lingers. Calorie counting may seem like a strange response to, say, speeding tickets, but it works for me.

The process also helped Tricia: As she therapized about her nutty family, her depression eased, transmogrifying her designated issue from a torture chamber to a study. Annabeth faced her marital dissatisfaction, got divorced, and lost 50 pounds. Sadly, Libbie never dealt with her dealing; she still obsesses about Prince Charming. But Kristen's fear for her children abated as she learned money management. If you have a designated issue, addressing other problems will (eventually) make it dry up and blow away. In its place you'll find self-empowerment and gratitude—even, weirdly, gratitude that your brain has the capacity to create another designated issue, should the blooming, buzzing confusion of your life ever require one.

Martha Beck is the author of six books, including Steering by Starlight (Rodale).

More Advice From Martha Beck