Feeling trapped by a job, relationship, or routine, but terrified of making a change? Martha Beck shows you how to feel your way to freedom.

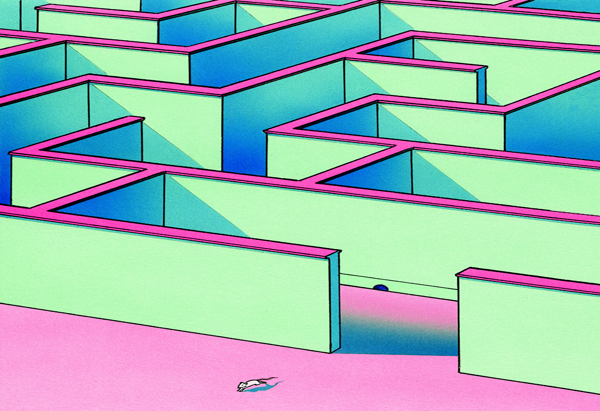

Illustration: Guy Billout

Sheila and I are conversing at a drug treatment center, where she's been remanded. Counselors are listening, so we can't plan a way to break her out. As it happens, escape is the last thing on Sheila's mind. I'm not coaching her through the woes of being institutionalized for drug use but prepping her for her upcoming release.

"In here everything's simple," Sheila says. "Outside I'll have to deal with my crazy mom, get a job, pay the bills. I don't know how to handle that without drugs." When I ask her to picture a peaceful, happy life, Sheila draws a blank. "I can't imagine anything except what I've already seen," she says.

The despair in her voice is so heavy it makes me want to huff a little glue myself, but two things give me hope: a fabled land known in the annals of psychology as Rat Park, and a montage of other clients, once as hopeless as Sheila, who went on to live happy, meaningful lives. The concepts I learned from Rat Park, channeled through the behaviors I've seen in those courageous clients, just may transform Sheila's future.

But first, what is this mythic Rat Park? And how might it relate to you? The term comes from a study conducted in 1981 by psychologist Bruce Alexander and colleagues. He noted that many addiction studies had something in common: The lab rats they used were locked in uncomfortable, isolating cages. Testing a hunch, Alexander gathered two groups of rats. For the first, he built a 200-square-foot rodent paradise called Rat Park. There a colony of white Wister rats found luxurious accommodations for all their favorite pastimes—mingling, mating, raising pups, writing articles for newspaper tabloids. The second group was housed in the traditional cages.

Alexander offered both groups a choice of plain water or sugar water laced with morphine. Like rats in other studies, the traditionally caged animals became instant addicts. However, the residents of Rat Park tended to "just say no," avoiding the drug-treated sugar water. Even rats that were already addicted to morphine tended to lay off the hard stuff when in Rat Park. Put them back in their cages, however, and they'd stay stoned as Deadheads.

Alexander saw many parallels between these junkie rats and human addicts. He has talked of one patient who worked as a shopping mall Santa. "He couldn't do his job unless he was high on heroin," Alexander remembered. "He would shoot up, climb into that red Santa Claus costume, put on those black plastic boots, and smile for six hours straight."

This story jingles bells for many of my clients. Like Smack Santa, they spend many hours playing roles that don't match their innate personalities and preferences, dulling the pain with mood-altering substances. Miserable with their jobs, relationships, or daily routines, they gulp down a fifth of Scotch, buy 46 commemorative Elvis plates on QVC, superglue phony smiles to their faces, and head on out to whatever rat race is gradually destroying them.

Sheila was actually a step ahead of most of my clients, in that she knew she was locked up. Most people are trapped in prisons made of mind stuff—attitudes and beliefs such as "I have to look successful" or "I can't disappoint my dad." Ideas like these—being deeply entrenched and invisible—are often more powerful than physical prisons. When we're trapped in mind cages, gulping happy pills by the handful and fantasizing about lethally stapling coworkers, we rarely even consider that our unhappiness comes from living in captivity. And if we ever come close to recognizing the truth, we're stopped by a barrage of terrifying questions: "What if there's nothing better than this?" "What if I quit my job, lose my seniority, and end up somewhere even worse?" "What if I break off this relationship and end up alone forever?" "What if I get my hopes up and the big break never comes?"

When the alternatives are staying in the familiar cage or facing the unknown, trust me, most people choose the cage—over and over and over again. It's painful to watch, especially knowing that liberation is only a few simple steps away. If you suspect that you might need to engineer your own prison break, the following pieces of commonsense advice can set you free forever.

"In here everything's simple," Sheila says. "Outside I'll have to deal with my crazy mom, get a job, pay the bills. I don't know how to handle that without drugs." When I ask her to picture a peaceful, happy life, Sheila draws a blank. "I can't imagine anything except what I've already seen," she says.

The despair in her voice is so heavy it makes me want to huff a little glue myself, but two things give me hope: a fabled land known in the annals of psychology as Rat Park, and a montage of other clients, once as hopeless as Sheila, who went on to live happy, meaningful lives. The concepts I learned from Rat Park, channeled through the behaviors I've seen in those courageous clients, just may transform Sheila's future.

But first, what is this mythic Rat Park? And how might it relate to you? The term comes from a study conducted in 1981 by psychologist Bruce Alexander and colleagues. He noted that many addiction studies had something in common: The lab rats they used were locked in uncomfortable, isolating cages. Testing a hunch, Alexander gathered two groups of rats. For the first, he built a 200-square-foot rodent paradise called Rat Park. There a colony of white Wister rats found luxurious accommodations for all their favorite pastimes—mingling, mating, raising pups, writing articles for newspaper tabloids. The second group was housed in the traditional cages.

Alexander offered both groups a choice of plain water or sugar water laced with morphine. Like rats in other studies, the traditionally caged animals became instant addicts. However, the residents of Rat Park tended to "just say no," avoiding the drug-treated sugar water. Even rats that were already addicted to morphine tended to lay off the hard stuff when in Rat Park. Put them back in their cages, however, and they'd stay stoned as Deadheads.

Alexander saw many parallels between these junkie rats and human addicts. He has talked of one patient who worked as a shopping mall Santa. "He couldn't do his job unless he was high on heroin," Alexander remembered. "He would shoot up, climb into that red Santa Claus costume, put on those black plastic boots, and smile for six hours straight."

This story jingles bells for many of my clients. Like Smack Santa, they spend many hours playing roles that don't match their innate personalities and preferences, dulling the pain with mood-altering substances. Miserable with their jobs, relationships, or daily routines, they gulp down a fifth of Scotch, buy 46 commemorative Elvis plates on QVC, superglue phony smiles to their faces, and head on out to whatever rat race is gradually destroying them.

Sheila was actually a step ahead of most of my clients, in that she knew she was locked up. Most people are trapped in prisons made of mind stuff—attitudes and beliefs such as "I have to look successful" or "I can't disappoint my dad." Ideas like these—being deeply entrenched and invisible—are often more powerful than physical prisons. When we're trapped in mind cages, gulping happy pills by the handful and fantasizing about lethally stapling coworkers, we rarely even consider that our unhappiness comes from living in captivity. And if we ever come close to recognizing the truth, we're stopped by a barrage of terrifying questions: "What if there's nothing better than this?" "What if I quit my job, lose my seniority, and end up somewhere even worse?" "What if I break off this relationship and end up alone forever?" "What if I get my hopes up and the big break never comes?"

When the alternatives are staying in the familiar cage or facing the unknown, trust me, most people choose the cage—over and over and over again. It's painful to watch, especially knowing that liberation is only a few simple steps away. If you suspect that you might need to engineer your own prison break, the following pieces of commonsense advice can set you free forever.

You Don't Have to Know What Rat Park Looks Like

"I just don't think I'll ever find the right life for me," Sheila frets.

"Of course you won't!" I say. "How strange to think you would!"

It amazes me how often people use that phrase: "Find the right life." Would you walk into your kitchen hoping to find the right fried egg, the right cup of coffee, the right toast? Such things don't simply appear before you; they arrive because you rummage around, figure out what's available, and make what you want. (If you're rich, you can hire a chef and place your order, but you're still creating the result.)

Bruce Alexander's rats were hand-delivered into paradise. Lucky critters, indeed—but not nearly as lucky as Alexander himself, or the rest of us humans, who have the astonishing ability to envision and build Rat Parks. All animals are shaped by their environment, but we, more than any other species, can shape our environment right back. We can cook the egg, brew the coffee, paint the room, change the space. We can fabricate our Rat Parks, and we must, if we want them built to spec.

"But I don't know what I'm trying to build," Sheila protests when I tell her this. "How can I create something when I don't have a clue what it looks like?"

Time for commonsense suggestion number two.

You Don't Need a Map to Find Your Rat Park

I often invite clients to play the dead-simple game You're Getting Warmer, You're Getting Colder. The client leaves the room, and I hide a simple object—say, a key—in a tricky place, such as the inside of a cake. (Not that I would have done this with someone locked up. Like Sheila. Absolutely not.) When the client returns to the room, he almost invariably stands still, and asks, "What am I looking for?"

Obviously, I don't answer him. The only feedback I'll give is "You're getting warmer" or "You're getting colder." Eventually clients will start moving. Guided by the words warmer and colder, they quickly identify the general hiding area. Then there's a period of confusion, fueled by assumptions like "Well, she certainly wouldn't hide it in the cake." They go back and forth for a bit, then stop and demand, "Where is it?" Again, this gets them nothing. Peeved, they revert to following the "warmer/colder" feedback until they arrive at the object.

I've never had a client who didn't ultimately succeed. Not one.

My point: Life has installed within you powerful "getting warmer, getting colder" signals. When Sheila thought of leaving the treatment center, her tension, anxiety, and drug cravings soared. The time she had to serve was "warmer"; her outside life, "colder." Certain activities were freezing cold—dealing with her mother, working, paying bills. As we examined each of these, we found that her guidance system was giving her beautifully clear messages. For instance, being around sane noncriminals, even officials at the treatment center, felt "warmer" than Sheila's crazy dope-dealing mother. Working in the cafeteria, with its institutional predictability, was "warmer" than her old cocktail waitress job, where she'd flashed her flesh to elicit unpredictable tips from drunken customers. Living within her economic means felt "warmer" than credit card shopping sprees she couldn't afford.

True, Sheila was a long way from her own Rat Park. But with the knowledge that her navigation system was functioning perfectly, all she had to do was play her life as a game of You're Getting Warmer, You're Getting Colder. The same is true for you. It isn't necessary to know exactly how your ideal life will look; you only have to know what feels better and what feels worse. If something feels both good and bad, break it down into its components to see which are warm, which cold. Begin making choices based on what makes you feel freer and happier, rather than how you think an ideal life should look. It's the process of feeling our way toward happiness, not the realization of some Platonic ideal, that creates our best lives.

"My life is so far from perfect," Sheila says as we end our session. "I don't know if it's fixable."

She's ready to hear my third and last piece of commonsense advice.

You Don't Have to Make Big Changes to Get There

This step is something I stole from philosopher and engineer Buckminster Fuller. Bucky, as his friends knew him, chose for his epitaph just three words: call me trimtab. Trim tabs are tiny rudders attached to the back of larger rudders that steer huge ships. The big rudders would snap off if turned directly, but, as Fuller famously said, "just moving the little trim tab builds a low pressure that pulls the rudder around. Takes almost no effort at all. So...you can just put your foot out like that and the whole big ship of state is going to go."

Every life is a series of trim-tab decisions. Should you read tonight or watch TV? Choose what feels warmer. Self-help or thriller? Choose what feels warmer. Cuddle with the dog or banish him from the bed? Choose what feels (psychologically) warmer.

If you make mistakes, no problem; you'll soon feel colder and correct your course. Making consistent trim-tab choices toward happiness is what steers the mighty ship of your life into exotic ports, safe havens—in short, into every Rat Park you can imagine, and then some.

I say goodbye to Sheila not knowing whether she'll set her trim tabs toward happiness or back to her drug-abusing cage of a life. I've learned not to get my hopes up with humans, who aren't nearly as clear-sighted and authentic as rats. But our session reminds me to keep following my own tiny feelings and impulses to their distant and amazing destinations. So instead of worrying about Sheila—or me, or you—I'll choose to trust our powerful instincts, our desire to be happy, our amazing human capacity for invention. You may choose cynical despair instead—it's all the rage in intellectual circles—but if you care to join me, I think you'll find it's a whole lot warmer over here in Rat Park.

Martha Beck is the author of six books. Her most recent is Steering by Starlight (Rodale).

More Martha Beck Advice