If you're spending all your time putting out fires—and never getting to the things that really matter—STOP! Martha Beck shows you the chart that draws a line between must-do-this-minute time killers and soul satisfiers.

Illustration: Knickerbocker

About a year ago, I watched a speech online about time management given in 1998 by Randy Pausch, PhD, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Pausch cautioned listeners not to waste energy on activities that seem urgent but aren't important. Choose instead, Pausch suggested, to spend time on activities that are deeply important, even if they don't seem critical.

That was an excellent speech. It would become extremely poignant in 2006, when the then 45-year-old Pausch was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Watching another of his speeches online—the famous "Last Lecture" (now a best-selling book), in which he teaches his three young children how to make their dreams come true—I wondered if this time management expert sensed, even back in 1998, that he'd spend less time on earth than anyone wished.

Pausch's work and his personal story drive home a lesson we all know but frequently forget: To live richly and avoid regret, we must give priority to things of real importance. But in a world where everything from your BlackBerry to your car's oil filter to your grandmother is competing for your limited time, this requires deliberate, consistent choice. The good news is that we can develop the habit of choosing what's really important over everything else. Life seems designed to teach us how to do this. Pay attention, and you'll notice that even when you're under "urgent" pressure to do something unimportant, it feels discordant and wrong. Do what really matters, and your life comes into harmonious alignment. Don't believe me? Apply the concepts that follow, and call me in the morning.

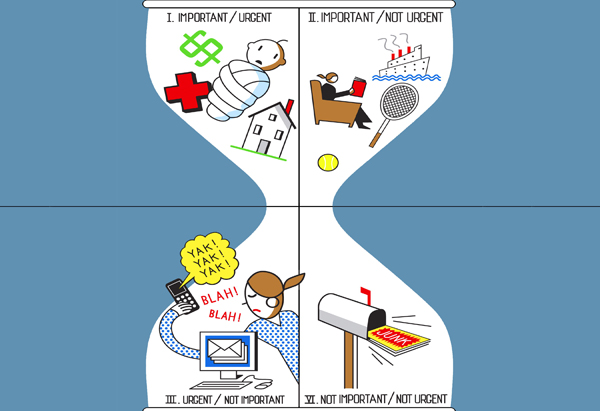

To me, Stephen Covey will always be the smart, funny guy on my high school debate team who, when it was time to be cross-examined by an opponent, would drop the "c" from the traditional phrase "I'm now open for cross-ex," so that it came out "I'm now open for raw sex." The judges never noticed, and the rest of us debaters thought Steve was hilarious. We also sort of knew that his dad, Stephen Covey Sr., was a renowned management guru. Randy Pausch was quoting Steve's dad when he proposed categorizing all activities on a matrix of apparent urgency and ultimate importance, like this:

As Covey observed, we almost always do the things in Quadrant I (stuff that's both important and urgent, like feeding the kids and paying the rent), and almost never get to Quadrant IV (like reading junk mail). That's good. However, we tend to focus on Quadrant III (urgent but not important things, like talking to a demanding co-worker about her rotten boyfriend) to the detriment of Quadrant II (no-deadline pastimes like writing a book, basking in nature's beauty, or taking time to be still). Covey proposed devoting less time to the dinky tasks, even those that are urgent, and more time to those things that are really important.

Here's an exercise he proposed:

That was an excellent speech. It would become extremely poignant in 2006, when the then 45-year-old Pausch was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Watching another of his speeches online—the famous "Last Lecture" (now a best-selling book), in which he teaches his three young children how to make their dreams come true—I wondered if this time management expert sensed, even back in 1998, that he'd spend less time on earth than anyone wished.

Pausch's work and his personal story drive home a lesson we all know but frequently forget: To live richly and avoid regret, we must give priority to things of real importance. But in a world where everything from your BlackBerry to your car's oil filter to your grandmother is competing for your limited time, this requires deliberate, consistent choice. The good news is that we can develop the habit of choosing what's really important over everything else. Life seems designed to teach us how to do this. Pay attention, and you'll notice that even when you're under "urgent" pressure to do something unimportant, it feels discordant and wrong. Do what really matters, and your life comes into harmonious alignment. Don't believe me? Apply the concepts that follow, and call me in the morning.

First (and Second) Things First

To me, Stephen Covey will always be the smart, funny guy on my high school debate team who, when it was time to be cross-examined by an opponent, would drop the "c" from the traditional phrase "I'm now open for cross-ex," so that it came out "I'm now open for raw sex." The judges never noticed, and the rest of us debaters thought Steve was hilarious. We also sort of knew that his dad, Stephen Covey Sr., was a renowned management guru. Randy Pausch was quoting Steve's dad when he proposed categorizing all activities on a matrix of apparent urgency and ultimate importance, like this:

As Covey observed, we almost always do the things in Quadrant I (stuff that's both important and urgent, like feeding the kids and paying the rent), and almost never get to Quadrant IV (like reading junk mail). That's good. However, we tend to focus on Quadrant III (urgent but not important things, like talking to a demanding co-worker about her rotten boyfriend) to the detriment of Quadrant II (no-deadline pastimes like writing a book, basking in nature's beauty, or taking time to be still). Covey proposed devoting less time to the dinky tasks, even those that are urgent, and more time to those things that are really important.

Here's an exercise he proposed:

- Get 20 or 30 notecards. On each card, write down one thing you should do, want to do, hope to do, plan to do, or dream of doing. Include everything, no matter how large or small. Keep this up until your brain runs dry.

- When you've written down all your goals, plans, and ideas, separate the cards into two piles: things that have to be done right this minute (or feel like it) and those that don't.

- Now go through both of these piles, separating each into "important" and "not important" stacks. The four resulting stacks correlate with the Covey Quadrants.

- Carefully place both your "not important" card stacks in a safe spot. This, if my experience is any indication, will ensure that you'll never find them again. If you do happen to stumble across them at any time in the future, burn them.

- Commit to eliminating from your schedule all the activities that didn't make it into the "important" stacks. If you have time after doing your important and urgent things, use it on important but not urgent activities. No matter how pressing something may seem to be, if it's not important, just don't do it.

From Theory to Practice: Living a Quadrant II Life

Planning to live this way is one thing; changing habits of thought and action is another. You're subjected to daily pressure to do things that, while unimportant in the long run, may seem unavoidable in the middle of a PTA meeting. Congratulate yourself every time you drop a Quadrant III activity and replace it with something from Quadrant II. Here are some substitutions I made after doing this exercise:

- Postponed promoting new book to raise money for research on Down syndrome.

- Canceled client meeting to bake my daughter's birthday cake.

- Blew off e-mail to chat on the phone with dear friend.

- Blew off e-mail to volunteer at local methadone clinic.

- Blew off e-mail to exercise.

- Blew off e-mail to bathe.

- Blew off e-mail to sleep.

- Blew off e-mail to sense a theme developing here.

At this point, I'd like to apologize to all of you who didn't receive an e-mail response from me this month. Blame Covey and Pausch. (Actually, thanks, Covey and Pausch!) E-mail may be crucially important to you, in which case it should get your consistent attention. But it amazed me, when I did the Quadrant exercise, how many of my urgent-seeming e-mails felt less important than working for people in need, caring for my health, or being with friends and family. I realized that I could easily spend all my time shoveling out the electronic Augean stables, missing countless small experiences that add up to my life's purpose.

How to Determine What's Important

As powerful as this exercise was for me, it posed a few vexing questions. Highly effective people seem to cut through life's complexities in bold, clean strokes; reading their books or watching their lectures, you can practically hear them telling their secretaries: "No, no, Mabel, can't you see that's urgent, but it's not important? And cancel my 5 o'clock; I'll be meeting with His Holiness the Pope instead."

By contrast, my prioritization is plagued with ambiguity. Is chasing my beagle round and round the sofa important? Urgent? Many would say it's neither, but Cookie clearly thinks it's both, and who am I to say he's wrong? I might dismiss Cookie's opinion on the grounds that he's small and furry, but what about, say, the authors who'd like me to promote their books? The stack of manuscripts in my office is taller than I am, and every volume is both urgent and important to its author. If you, like me, tend to include other people's priorities in your decision-making, the Covey Quadrant exercise requires you to break that pattern. You can't differentiate between "this is due today" and "this is important" when you are (to quote the 15th-century mystic Kabir) "tangled up in others." You must untangle yourself, still all other voices, and go to the deepest place within to know what's important and urgent in your unique and singular life.

This can be difficult at first, but as you focus on it, you'll discover a beautiful surprise: Your life has been waiting for just this opportunity to help you choose what's right for you, even when other people (and the occasional beagle) are telling you that their own code-red desires should take priority. It does this like a good psychological behaviorist, by making things difficult and taxing when they're not important, delicious and relatively effortless when they are.

When I say this to new clients, they look at me cynically, as if I've promised them a unicorn. But when they begin paying attention, they soon notice how good life feels when they're doing what thrills them, and how bad it feels when they're not. The bad feeling is most noticeable at first; a sense of awkwardness, like petting a cat from back to front. Tasks go badly. My clients forget things: their keys, their wallets, the way to the office. Conversations are stilted. Energy ebbs without ever flowing. If these clients don't change course, unease may grow into anger, depression, health problems, or total burnout.

This feels awful, but the uncomfortableness is a wonderful incentive to begin finding out how good a life of real significance can feel. Drop what's unimportant and replace it with activities from Covey Quadrant II—things that replenish your physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being—and suddenly, everything becomes much easier. Energy returns, anger disappears, you begin smiling spontaneously. The cat stops generating static electricity, and starts to purr.

To follow your life's guidance, you may have to reassign some seemingly important things to "unimportant." If you believe that pleasing your horrible boss or having a spotless house is a higher priority than playing with your children or sleeping off the flu, be prepared for a long and strenuous battle against destiny. Also, be prepared to lose. And after you've lost, go online and watch Randy Pausch's last lecture. In Pausch, who died on July 25, you'll see the clarity and joy of a man who chose all along to do what really mattered. That's no consolation prize; that's true victory.

As you focus more on what's important to your soul, filling your schedule with the kinds of things that are vital though maybe not due this minute, every day will bring more enjoyment and refreshment. You'll be fascinated and invigorated, open to everything from artistic creativity to (in the legendary words of Stephen Covey Jr.) "raw sex."

"This is the true joy in life," wrote George Bernard Shaw, "the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one. ... Life is no 'brief candle' for me. It is a sort of splendid torch, which I have got hold of for the moment; and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations." This is the credo of Quadrant II. Abide by it, and you'll find a path that illuminates the world for you and others, even after you're gone. No matter what others may think, say, or do, your whole life will become a blaze of glory.

More Martha Beck Advice