After a blissful courtship, Helyn Trickey Bradley married the man of her dreams. She loved his two daughters, his charming house—but could she love his dead first wife, too?

Photo: Courtesy of the Bradley Family

I have a laundry list of reasons for hating the blue recliner: It's lumpy; it's too big for the room; it's covered with scratches from a dog I never knew. It looks like it might've been peed on or accidentally left out in the rain. And it belonged to my husband's dead wife, Karen.

Over and over again, I turn it to face the rest of the room, but because of a slight slope in the floor, the chair stubbornly swivels to face a bookcase that holds a framed photo of Karen sitting in the rumble seat of a Model A with her two young daughters, her blonde, chin-length hair shimmering in the sun. I dig up a photo of Gary and me taken after we got engaged, our arms woven tightly, our eyes wide like we're boarding the biggest ride at the fair. I place our photo on the bookcase, nudging it next to the picture of Karen and the girls. The frames touch, they are so close. Still, the chair nags at me. I want it gone.

"It's comfortable," Gary argues. "It's functional."

I tell him it looks like it belongs in a fraternity house.

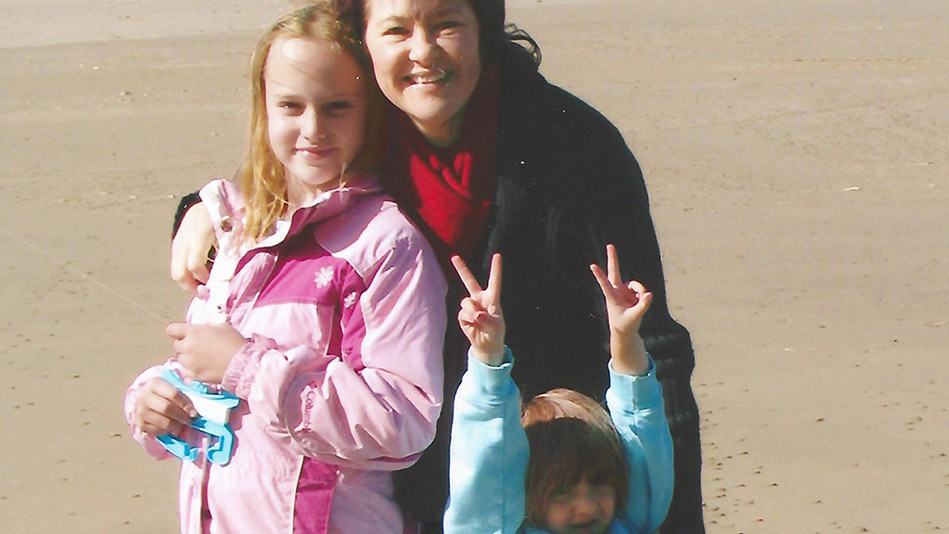

I married Gary, a widower with two young daughters, after a whirlwind romance, the kind with such velocity that it confounds everyone but the two people at its center. We met online, then had dinner on a sticky night in August, when only mosquitoes and lovers linger on park benches. We broke most of the first date rules: He told me of the pain of losing his wife to cancer and the challenges of helping his daughters through their grief. I told him about the toxic decade-long relationship that had left me pessimistic about finding lasting love. By midnight, we'd both admitted that we were open to getting married—him again and me for the first time. It felt like we were spinning through the universe, two shooting stars shivering with speed. The following month, Gary introduced me to his daughters: Tonya, 12, energetic and twinkly eyed, and Lizzie, a 5-year-old with a honey-colored bob and a jack-o'-lantern smile. Three months later, we were engaged. Less than a year after our first date, I became, at 41, a first-time wife and mother of two. In so many ways it was a dream come true, and I wanted badly to believe that moving into the home Gary had shared with Karen would be as seamless and wonderful as falling in love with her husband had been. Loving Gary was easy. Loving Gary's daughters was easy. Loving Karen was not.

The house was saturated with her. When we made peppermint tea, we used Karen's kettle. When we baked pumpkin muffins, we used Karen's oven mitts. Mail addressed to her still came to the house. I'd hoped I would grow to treasure Karen's primary-colored Fiesta dishes, her wedding dress, pressed and hanging at the back of our closet, waiting for Tonya or Lizzie. Instead, I wondered what kind of woman would buy a gingham shower curtain and leave the walls in her home a numbing shade of Landlord White. I resented the recipe notes, penned in her no-frills handwriting, that dropped out of her vegetarian cookbooks. In my heart, I knew that it was irrational to envy a dead person, someone who would never watch her daughters sing solos in school plays or wave goodbye to them as they shuffled nervously out the front door on first dates. But I couldn't help it: I wanted to claw the ruffled valances she'd hung in the kitchen. I even started drinking my morning coffee without cream to delay confronting the photo of Karen and Tonya taped to the refrigerator.

Gary and I had dismissed the idea of selling the house; the economy was sagging, and real estate was not fetching the prices it once had. More important, we didn't want to move the girls from the only home they'd known so soon after losing their mother. And anyway, I liked the white cottage with the picket fence, snuggled in amid towering Douglas firs on a street where neighbors waved. I was sure that with a little paint and some new furniture, the house Karen and Gary had renovated could become my home, too.

So we painted. We bought a lovely sofa set and changed the shower curtains. We tore out the wood-burning stove in the living room in favor of a gas fireplace. I arranged my John Updike novels and volumes of Mary Oliver's poetry on the bookshelves. But the blue chair remained—and so, it seemed, did Karen's hold on my house.

Over and over again, I turn it to face the rest of the room, but because of a slight slope in the floor, the chair stubbornly swivels to face a bookcase that holds a framed photo of Karen sitting in the rumble seat of a Model A with her two young daughters, her blonde, chin-length hair shimmering in the sun. I dig up a photo of Gary and me taken after we got engaged, our arms woven tightly, our eyes wide like we're boarding the biggest ride at the fair. I place our photo on the bookcase, nudging it next to the picture of Karen and the girls. The frames touch, they are so close. Still, the chair nags at me. I want it gone.

"It's comfortable," Gary argues. "It's functional."

I tell him it looks like it belongs in a fraternity house.

I married Gary, a widower with two young daughters, after a whirlwind romance, the kind with such velocity that it confounds everyone but the two people at its center. We met online, then had dinner on a sticky night in August, when only mosquitoes and lovers linger on park benches. We broke most of the first date rules: He told me of the pain of losing his wife to cancer and the challenges of helping his daughters through their grief. I told him about the toxic decade-long relationship that had left me pessimistic about finding lasting love. By midnight, we'd both admitted that we were open to getting married—him again and me for the first time. It felt like we were spinning through the universe, two shooting stars shivering with speed. The following month, Gary introduced me to his daughters: Tonya, 12, energetic and twinkly eyed, and Lizzie, a 5-year-old with a honey-colored bob and a jack-o'-lantern smile. Three months later, we were engaged. Less than a year after our first date, I became, at 41, a first-time wife and mother of two. In so many ways it was a dream come true, and I wanted badly to believe that moving into the home Gary had shared with Karen would be as seamless and wonderful as falling in love with her husband had been. Loving Gary was easy. Loving Gary's daughters was easy. Loving Karen was not.

The house was saturated with her. When we made peppermint tea, we used Karen's kettle. When we baked pumpkin muffins, we used Karen's oven mitts. Mail addressed to her still came to the house. I'd hoped I would grow to treasure Karen's primary-colored Fiesta dishes, her wedding dress, pressed and hanging at the back of our closet, waiting for Tonya or Lizzie. Instead, I wondered what kind of woman would buy a gingham shower curtain and leave the walls in her home a numbing shade of Landlord White. I resented the recipe notes, penned in her no-frills handwriting, that dropped out of her vegetarian cookbooks. In my heart, I knew that it was irrational to envy a dead person, someone who would never watch her daughters sing solos in school plays or wave goodbye to them as they shuffled nervously out the front door on first dates. But I couldn't help it: I wanted to claw the ruffled valances she'd hung in the kitchen. I even started drinking my morning coffee without cream to delay confronting the photo of Karen and Tonya taped to the refrigerator.

Gary and I had dismissed the idea of selling the house; the economy was sagging, and real estate was not fetching the prices it once had. More important, we didn't want to move the girls from the only home they'd known so soon after losing their mother. And anyway, I liked the white cottage with the picket fence, snuggled in amid towering Douglas firs on a street where neighbors waved. I was sure that with a little paint and some new furniture, the house Karen and Gary had renovated could become my home, too.

So we painted. We bought a lovely sofa set and changed the shower curtains. We tore out the wood-burning stove in the living room in favor of a gas fireplace. I arranged my John Updike novels and volumes of Mary Oliver's poetry on the bookshelves. But the blue chair remained—and so, it seemed, did Karen's hold on my house.

Photo: Courtesy of the Bradley Family

I was jealous that Karen had loved my husband for 17 years. She'd known him as a young man, when starting his own woodworking business was just a dream he whispered about under the covers. Karen had loved my husband before children, when, I imagined, sleeping late, romantic weekends at the coast, and long, uninterrupted conversations were routine. I hated learning that Gary had proposed to Karen on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Pausing to study their wedding photo in a corner of Gary's home office, I spied a young couple squinting and ecstatic in the sun outside the Chapel of Love in Las Vegas, grinning like they'd just pulled off a bank heist.

I've had girlfriends, most of them sane and successful, who've made voodoo dolls out of their lover's ex-wives or past girlfriends. I can't do that to Karen: It's distasteful to speak ill of the dead, much less stick effigies of them with pins. I can't even complain about her to my girlfriends without feeling like a heel.

*

To commemorate Karen's death each April, Gary and the girls release balloons with messages they've written on paper hearts attached to the strings. On the second anniversary of her death, Gary and I had been engaged for four months. I knew I was officially part of the family when Tonya and Lizzie selected a red balloon for me to release, too. But I had trouble writing a message. I wasn't sure what Karen would want to hear from me, the woman who'd sneaked into her house, slept with her husband and presumed to know how to mother her two babies. I sat with a pencil poised over my blank paper heart. Finally I just scribbled "thank you" and quickly folded the paper twice so no one could glimpse what I'd written. It felt like such a silly, weak message, but what could I say? The truth and incredible irony is that Gary, Tonya and Lizzie's loss had been my gain.

One summer, while Gary, the girls, and I were on the Oregon coast, we stopped at a favorite local restaurant following an afternoon spent building sand castles and splashing in the frigid Pacific. As we waited for our cheeseburgers and fries, I leaned over and brushed some sand from Tonya's eyebrows. Someone at the table, maybe Lizzie, began to hum, and soon the whole family was singing "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain" and laughing about how none of us except Gary could remember the lyrics. We were still singing when Tonya looked at me and stopped short, her face stricken. She turned her gaze to the ocean tumbling outside the window, but the tears at the edges of her eyes told me what had happened: She'd lost herself in time and had turned toward me expecting to see Karen.

I've had girlfriends, most of them sane and successful, who've made voodoo dolls out of their lover's ex-wives or past girlfriends. I can't do that to Karen: It's distasteful to speak ill of the dead, much less stick effigies of them with pins. I can't even complain about her to my girlfriends without feeling like a heel.

One summer, while Gary, the girls, and I were on the Oregon coast, we stopped at a favorite local restaurant following an afternoon spent building sand castles and splashing in the frigid Pacific. As we waited for our cheeseburgers and fries, I leaned over and brushed some sand from Tonya's eyebrows. Someone at the table, maybe Lizzie, began to hum, and soon the whole family was singing "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain" and laughing about how none of us except Gary could remember the lyrics. We were still singing when Tonya looked at me and stopped short, her face stricken. She turned her gaze to the ocean tumbling outside the window, but the tears at the edges of her eyes told me what had happened: She'd lost herself in time and had turned toward me expecting to see Karen.

Photo: Courtesy of the Bradley Family

We hadn't been together a year when Gary and I were happy to discover that I was pregnant. During my second trimester, we learned that our baby was too small, and the doctor advised bed rest. Heavy and uncomfortable, I spent my days sipping protein shakes and drifting in and out of fitful naps. Gary and the girls would gather in the bedroom each afternoon and tell me their news. It occurred to me that they must have done the same during Karen's final months. As her body withered in hospice care, Karen's adjustable home hospital bed had been placed along the west wall to give her a view of the busy dining room. My queen-size sleigh bed now sat in the same place—but while I was lying under the covers waiting for a new life to take hold, Karen had been waiting for her own to end.

Twisting in a tangle of sheets, I thought about how Karen, too, must have looked out the window to see the neighbors trudge through the drizzle with golden retrievers tugging on their leashes. Surely she also saw the school bus motor down our quiet street every afternoon, filled with boisterous children. Maybe Karen lifted her head and smiled when she heard the thumping of small feet, Tonya's earnest attempts to channel Adele, and Lizzie's lament of "I'm hungry!"

I began to grill Gary for details about this woman whose life I'd come to inhabit. From him I learned that Karen had planted King Edward daffodil bulbs each fall, that she made her own granola, that she could watch any movie starring Cary Grant ten times without tiring. Gary told me how on a blustery Friday afternoon in February 2009, Karen had gathered her daughters close on her bed and, with Gary's help, explained that the bad cells were beating the good cells, and that she was going to die. Lying there in the room we shared, I couldn't imagine how she'd summoned the courage.

Every so often during those months of bed rest, when Gary and the girls were out, I'd wander through the quiet house, letting my fingertips drift along the same counter tops that Karen's hands had touched. I'd sit at the dining room table, clutching a mug of ginger tea and a box of Saltines, fighting off morning sickness. And I'd wonder whether Karen, who had miscarried twice before she and Gary adopted Tonya and Lizzie, had sat at this same table feeling sick to her stomach. I was certain that she'd experienced the anxiety that was now consuming me, the heavy possibility of so much loss. In life, we have little control over whom we fall in love with and when; which babies flourish in our bellies and which don't; when we die and whom we leave behind, bobbing and gulping in our wake.

In January 2012, I delivered a healthy baby girl, and Gary and I became swamped with around-the-clock feedings, diaper changes, and swaddling and reswaddling our squirmy infant. I was so overwhelmed by new motherhood that I nearly forgot my jealousy of Karen—until one afternoon when I sank deep into her old blue chair to feed my daughter. Holding my warm baby, I lifted my foot and the recliner swiveled to face the bookcase. From there, I could see an array of photos: Gary and me at our wedding; Tonya and Lizzie goofing around at the beach; our newborn, her hair wet from the bath, her eyes starry with wonder. I felt a sudden surge of gratitude for my oddly constructed family—including Karen, who will always be here: in photos, in memories joyous and heartbreaking, in her careful recipe notes, and in her blue chair, which still isn't pretty, but is starting to feel like home.

Twisting in a tangle of sheets, I thought about how Karen, too, must have looked out the window to see the neighbors trudge through the drizzle with golden retrievers tugging on their leashes. Surely she also saw the school bus motor down our quiet street every afternoon, filled with boisterous children. Maybe Karen lifted her head and smiled when she heard the thumping of small feet, Tonya's earnest attempts to channel Adele, and Lizzie's lament of "I'm hungry!"

I began to grill Gary for details about this woman whose life I'd come to inhabit. From him I learned that Karen had planted King Edward daffodil bulbs each fall, that she made her own granola, that she could watch any movie starring Cary Grant ten times without tiring. Gary told me how on a blustery Friday afternoon in February 2009, Karen had gathered her daughters close on her bed and, with Gary's help, explained that the bad cells were beating the good cells, and that she was going to die. Lying there in the room we shared, I couldn't imagine how she'd summoned the courage.

Every so often during those months of bed rest, when Gary and the girls were out, I'd wander through the quiet house, letting my fingertips drift along the same counter tops that Karen's hands had touched. I'd sit at the dining room table, clutching a mug of ginger tea and a box of Saltines, fighting off morning sickness. And I'd wonder whether Karen, who had miscarried twice before she and Gary adopted Tonya and Lizzie, had sat at this same table feeling sick to her stomach. I was certain that she'd experienced the anxiety that was now consuming me, the heavy possibility of so much loss. In life, we have little control over whom we fall in love with and when; which babies flourish in our bellies and which don't; when we die and whom we leave behind, bobbing and gulping in our wake.

In January 2012, I delivered a healthy baby girl, and Gary and I became swamped with around-the-clock feedings, diaper changes, and swaddling and reswaddling our squirmy infant. I was so overwhelmed by new motherhood that I nearly forgot my jealousy of Karen—until one afternoon when I sank deep into her old blue chair to feed my daughter. Holding my warm baby, I lifted my foot and the recliner swiveled to face the bookcase. From there, I could see an array of photos: Gary and me at our wedding; Tonya and Lizzie goofing around at the beach; our newborn, her hair wet from the bath, her eyes starry with wonder. I felt a sudden surge of gratitude for my oddly constructed family—including Karen, who will always be here: in photos, in memories joyous and heartbreaking, in her careful recipe notes, and in her blue chair, which still isn't pretty, but is starting to feel like home.