Skewed Self-Image

In the "doll experiment" from the 1940s, husband-and-wife psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark asked black children to tell them which doll—a white one or a black one—they thought looked most like them, and which was good and which was bad. They found that black children identified with and preferred white dolls to black ones. They concluded this was proof of internalized racism. Their research later became cornerstone evidence in the landmark Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision of Topeka, Kansas, which ended American school segregation.

In 2005, 18-year-old filmmaker Kiri Davis recreated the Clarks' experiment with 21 young black children at a daycare center in New York. In her seven-minute documentary, A Girl Like Me, Kiri presented the children with two dolls—a black one and a white one. Then, like in the original experiment, Kiri asked which they would rather play with and which they thought was "nice" and which was "bad."

In 2005, 18-year-old filmmaker Kiri Davis recreated the Clarks' experiment with 21 young black children at a daycare center in New York. In her seven-minute documentary, A Girl Like Me, Kiri presented the children with two dolls—a black one and a white one. Then, like in the original experiment, Kiri asked which they would rather play with and which they thought was "nice" and which was "bad."

As in the original test, Kiri found that most of the black children preferred the white dolls and identified the black dolls as "bad." "I think those attitudes that existed 50 years ago are still here. They're not highlighted, and they're kind of on the down low, but they still exist," Kiri says. "These children, even though they're 4 and 5 years old, they're kind of like a mirror and they show exactly what they've been exposed to by society."

Kiri says she hoped the documentary would highlight for people how subtle messages—like those in the media and through product marketing—affect children. "I thought you could tell people all you want about how certain standards are affecting self-esteem and self-image, but [when] you show them, that's when they'll get it," Kiri says. "That's what I thought the doll test might do."

Even still, Kiri says she was surprised by the reaction A Girl Like Me provoked. It won an award from the Media That Matters film festival and was featured on news reports around the world. The documentary is available on the Internet and has been used to spark classroom discussions. "I thought maybe the doll test might hit some nerve in America, but I didn't think to that extent," she says.

Kiri says she hoped the documentary would highlight for people how subtle messages—like those in the media and through product marketing—affect children. "I thought you could tell people all you want about how certain standards are affecting self-esteem and self-image, but [when] you show them, that's when they'll get it," Kiri says. "That's what I thought the doll test might do."

Even still, Kiri says she was surprised by the reaction A Girl Like Me provoked. It won an award from the Media That Matters film festival and was featured on news reports around the world. The documentary is available on the Internet and has been used to spark classroom discussions. "I thought maybe the doll test might hit some nerve in America, but I didn't think to that extent," she says.

Kiri decided to replicate the doll experiment because of issues of intraracist beauty that she and her friends faced. In the black community, those who have more European features are put on pedestals she says. Kiri also says people with straighter hair or lighter skin are often considered beautiful, while those with more African features are considered not beautiful. "[The documentary] was a way to kind of put [our feelings] out there so it didn't seem so taboo or uncomfortable to talk about, so people couldn't just push it under the table."

Ursula, Kiri's mother, says her daughter's documentary accurately illustrates how society and media's narrow concept of beauty affects the self-esteem of children. "The imagery is so very powerful and kids see these images time and time again, and they internalize them," she says. "The message that comes from these negative images and stereotypes, it really says, 'We don't value you.' It hits the core of who you are and your self-esteem and self-worth."

Kiri says overturning these skewed ideas of beauty is everyone's responsibility. We each have to begin by "not letting others define you, and … celebrating your soul and creating that foundation."

Ursula, Kiri's mother, says her daughter's documentary accurately illustrates how society and media's narrow concept of beauty affects the self-esteem of children. "The imagery is so very powerful and kids see these images time and time again, and they internalize them," she says. "The message that comes from these negative images and stereotypes, it really says, 'We don't value you.' It hits the core of who you are and your self-esteem and self-worth."

Kiri says overturning these skewed ideas of beauty is everyone's responsibility. We each have to begin by "not letting others define you, and … celebrating your soul and creating that foundation."

On the mega-hit show Grey's Anatomy, Chandra Wilson plays resident surgeon Dr. Miranda Bailey. But she wasn't necessarily who the show's creators had in mind. "My role was originally intended for a short, white, blonde female," she says.

In her real life, Chandra is the mother of three children—a 16-month-old boy and two girls, ages 8 and 13. When she won a Screen Actors Guild Award in 2007, her speech specifically mentioned what the award would mean to her daughters. "Just to be able to take this thing home to my girls in particular and hold it in front of them and say, 'Look. With this skin and this nose and this height and these arms, you know, I'm here,'" Chandra said. "Thank you, Screen Actors Guild, for taking me as I am."

Chandra says her self-concept development is still "a work in progress." "I have to affirm that for myself a lot of times that I'm good enough already, just right here in this skin, where I am," she says. "That I shouldn't have to wait until my nose changes shape or if I start bleaching my skin."

In her real life, Chandra is the mother of three children—a 16-month-old boy and two girls, ages 8 and 13. When she won a Screen Actors Guild Award in 2007, her speech specifically mentioned what the award would mean to her daughters. "Just to be able to take this thing home to my girls in particular and hold it in front of them and say, 'Look. With this skin and this nose and this height and these arms, you know, I'm here,'" Chandra said. "Thank you, Screen Actors Guild, for taking me as I am."

Chandra says her self-concept development is still "a work in progress." "I have to affirm that for myself a lot of times that I'm good enough already, just right here in this skin, where I am," she says. "That I shouldn't have to wait until my nose changes shape or if I start bleaching my skin."

Chandra says that she had a defining moment during a beauty pageant when she was just 6 years old. "After I finished my little runway time, I came off the stage and one of the other white contestants said, 'You know you're not going to win.' I said, 'How do you know?' And she said, 'Because you're a nigger.'

"So I went back and I said, 'Mom, the girl just told me I wasn't going to win because I'm a nigger.' And my mom said, 'No, you're not going to win because you left that whole middle section out, the lines. We had rehearsed that!'"

Chandra proved both of them wrong by taking the top prize at the pageant. "The thing that, that taught me was, first of all, that word doesn't mean anything, obviously, because I'm standing there with the trophy," she says. "But it also said I don't even have to be perfect. … [I have] what I have and that's good enough."

"So I went back and I said, 'Mom, the girl just told me I wasn't going to win because I'm a nigger.' And my mom said, 'No, you're not going to win because you left that whole middle section out, the lines. We had rehearsed that!'"

Chandra proved both of them wrong by taking the top prize at the pageant. "The thing that, that taught me was, first of all, that word doesn't mean anything, obviously, because I'm standing there with the trophy," she says. "But it also said I don't even have to be perfect. … [I have] what I have and that's good enough."

Chandra says seeing Kiri's documentary about the doll experiment was eye-opening as a mother. "The thing that struck me the most was how quickly the kids answered the question. You know, 'This one is the nicest because she's white.' There was no ambiguity. There was no, 'Let me think about it.'"

She says her daughters have had dolls of varying races. "My 8-year-old is really into whose hair she can comb, so if there's a doll with hair that doesn't work out, she doesn't want to work with that one," Chandra says. "It doesn't matter what the ethnicity is. It's all about the hair for her."

Though she says her daughters seem to have no self-esteem issues, Chandra says she needs to remember to keep communicating with her girls. "I think that I don't even have to have the conversation. But that's not really true. I still have to bring up the conversation. 'What do you think about yourself? How do you think you look?'"

She says her daughters have had dolls of varying races. "My 8-year-old is really into whose hair she can comb, so if there's a doll with hair that doesn't work out, she doesn't want to work with that one," Chandra says. "It doesn't matter what the ethnicity is. It's all about the hair for her."

Though she says her daughters seem to have no self-esteem issues, Chandra says she needs to remember to keep communicating with her girls. "I think that I don't even have to have the conversation. But that's not really true. I still have to bring up the conversation. 'What do you think about yourself? How do you think you look?'"

As a child, Tangela says she was teased and tormented by other African-Americans because of her dark complexion. Then, when she was 19 years old, Tangela found out she was pregnant with her first child. While most expectant mothers just hope for a healthy child, Tangela prayed for something more.

"I would just say to God, 'Please don't make my son dark. Please don't make my child dark,'" she says. "I didn't want him to experience what I experienced…being called names, being talked about."

When Tangela's son, Najee, was born with dark skin, she says her heart ached for his future. "I saw people looking at him as if something was wrong with him," she says. "That's the pain that I really felt, more so than my own darkness."

"I would just say to God, 'Please don't make my son dark. Please don't make my child dark,'" she says. "I didn't want him to experience what I experienced…being called names, being talked about."

When Tangela's son, Najee, was born with dark skin, she says her heart ached for his future. "I saw people looking at him as if something was wrong with him," she says. "That's the pain that I really felt, more so than my own darkness."

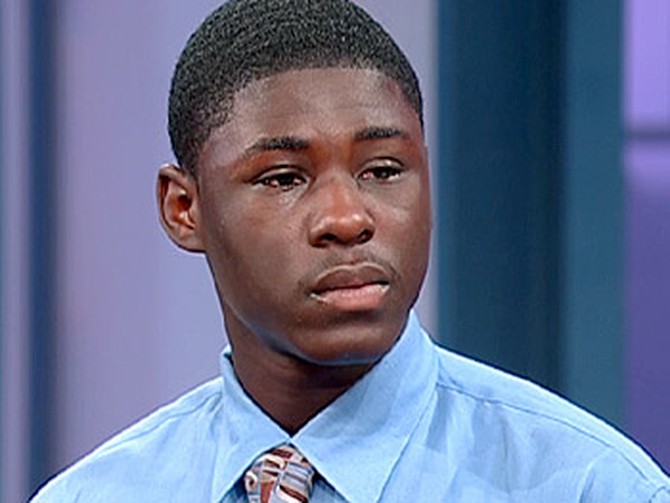

When Najee was 5 years old, children started teasing him about his complexion. In kindergarten, he says a female classmate, who was also African-American, made a hurtful remark that he remembers to this day. "The negative comment was, 'Oh, you're so black," he says.

As Najee grew older, the insults continued. "I've been called names like darkie, dark chocolate, blackie," he says. "Most of my negative comments do come from other blacks, and it's extremely painful."

Najee says he tries to hide his deep-seated insecurities from his friends and family by pretending to be happy. But deep down, a lifetime of low self-esteem is starting to take a toll on him. "Sometimes I have felt that I didn't even want to be on this earth," he says. "Sometimes I wish that God didn't make me this way."

His mother says her biggest regret is not understanding how much pain Najee has been feeling over the years. Tangela says she tried asking Najee if anyone teased him, but he never wanted to discuss it.

"I tried to give him books and encouragement and let him know he was beautiful. He had beautiful teeth," she says. "It almost didn't matter how much I told him because I didn't know what was going on."

As Najee grew older, the insults continued. "I've been called names like darkie, dark chocolate, blackie," he says. "Most of my negative comments do come from other blacks, and it's extremely painful."

Najee says he tries to hide his deep-seated insecurities from his friends and family by pretending to be happy. But deep down, a lifetime of low self-esteem is starting to take a toll on him. "Sometimes I have felt that I didn't even want to be on this earth," he says. "Sometimes I wish that God didn't make me this way."

His mother says her biggest regret is not understanding how much pain Najee has been feeling over the years. Tangela says she tried asking Najee if anyone teased him, but he never wanted to discuss it.

"I tried to give him books and encouragement and let him know he was beautiful. He had beautiful teeth," she says. "It almost didn't matter how much I told him because I didn't know what was going on."

Psychologist Dr. Robin Smith says Najee's negative self-image wasn't caused by teasing and name-calling…his mother's self-hatred is actually the root of the problem.

Without realizing it, Tangela allowed the wounds she suffered as a child affect the way she raised her son, Dr. Robin says. Instead, Tangela should have asked God to heal her of her own self-hatred instead of praying for a light-skinned child.

"You love your son. That I know. And he loves you, and I see that," Dr. Robin says. "But his biggest wounder, and lover, has been you. His biggest wounder has been you, because you prayed before he was even outside of your womb, 'God, change him.'"

Dr. Robin cites the fact that when Tangela discusses her son's beauty, she mentions his teeth…not his skin tone. "What you didn't talk about is the beauty of that brown skin," she says. "And I wouldn't expect yet that you could do it because you don't know yourself, in this moment, that you're beautiful."

Although Tangela says her family never made her feel self-conscious about her dark skin, Dr. Robin says someone close to her must have caused the wounds that she carried into adulthood. "Only somebody who's close to you can cause that kind of injury," Oprah says.

Before Tangela can help her son, Dr. Robin says she has to help herself. "The work is to identify where your self-hatred really begins," she says. "You want to communicate something to him? You've got to communicate it to you. You want to educate him about his beauty? You've got to educate yourself."

Without realizing it, Tangela allowed the wounds she suffered as a child affect the way she raised her son, Dr. Robin says. Instead, Tangela should have asked God to heal her of her own self-hatred instead of praying for a light-skinned child.

"You love your son. That I know. And he loves you, and I see that," Dr. Robin says. "But his biggest wounder, and lover, has been you. His biggest wounder has been you, because you prayed before he was even outside of your womb, 'God, change him.'"

Dr. Robin cites the fact that when Tangela discusses her son's beauty, she mentions his teeth…not his skin tone. "What you didn't talk about is the beauty of that brown skin," she says. "And I wouldn't expect yet that you could do it because you don't know yourself, in this moment, that you're beautiful."

Although Tangela says her family never made her feel self-conscious about her dark skin, Dr. Robin says someone close to her must have caused the wounds that she carried into adulthood. "Only somebody who's close to you can cause that kind of injury," Oprah says.

Before Tangela can help her son, Dr. Robin says she has to help herself. "The work is to identify where your self-hatred really begins," she says. "You want to communicate something to him? You've got to communicate it to you. You want to educate him about his beauty? You've got to educate yourself."

Most teens recognize SuChin Pak from her glamorous gig as a MTV host and correspondent. She was the first Asian face featured on the hip cable channel, and since her debut in 2001, she's interviewed hundreds of rock stars and tackled some of the toughest issues facing teens today.

In her documentary series, My Life (Translated), SuChin turned the camera on herself to reveal what it's like to be caught between two cultures.

When SuChin was a child, her family immigrated to the United States from Korea. Growing up, she says she never felt like she fit the Korean or the American standard of beauty.

"I didn't feel like I was pretty anywhere," she says. "I didn't fit into my own Korean family's standard of beauty because my parents and my family [think] eyes with creases are prettier. They're bigger. They're more open. … I don't have a crease in my eye. My whole life, all I ever wanted was this stupid centimeter of a freaking fold in my eye."

The crease, SuChin explains, is a fold of skin that some people have on their eyelid (see photo), which makes the eye appear larger. It's such a desirable quality that SuChin says many Asian girls use beauty products—like skin closures, tape, applicators and waterproof eyelash adhesive—to create an artificial crease. Some women even resort to plastic surgery, which can create a permanent crease.

In her documentary series, My Life (Translated), SuChin turned the camera on herself to reveal what it's like to be caught between two cultures.

When SuChin was a child, her family immigrated to the United States from Korea. Growing up, she says she never felt like she fit the Korean or the American standard of beauty.

"I didn't feel like I was pretty anywhere," she says. "I didn't fit into my own Korean family's standard of beauty because my parents and my family [think] eyes with creases are prettier. They're bigger. They're more open. … I don't have a crease in my eye. My whole life, all I ever wanted was this stupid centimeter of a freaking fold in my eye."

The crease, SuChin explains, is a fold of skin that some people have on their eyelid (see photo), which makes the eye appear larger. It's such a desirable quality that SuChin says many Asian girls use beauty products—like skin closures, tape, applicators and waterproof eyelash adhesive—to create an artificial crease. Some women even resort to plastic surgery, which can create a permanent crease.

The eyelid crease is so important, SuChin says, that it's now the number one plastic surgery in all of Asia. "I'm not talking about Asians [in America]," she says. "I'm talking about Asians abroad. … You can't even say it's because I've grown up here in America and I've only seen a certain type of beauty. It's everywhere."

In fact, she says the eyes are the most talked about thing, when it comes to body image or beauty, among Asians.

Unlike breast augmentations or face-lifts, the eyelid surgery has a different connotation in the Asian community. "For me and my family, this eyelid surgery wasn't like getting bigger boobs," she says. "It wasn't a vanity thing. It really, really was this belief that if you looked a little more Western [and] a little less Asian, it's like having a great degree from a better school. Or it's like having another skill. It was something to put in your portfolio."

For years, SuChin says she considered getting the surgery. She even went in for preliminary medical consultations.

In fact, she says the eyes are the most talked about thing, when it comes to body image or beauty, among Asians.

Unlike breast augmentations or face-lifts, the eyelid surgery has a different connotation in the Asian community. "For me and my family, this eyelid surgery wasn't like getting bigger boobs," she says. "It wasn't a vanity thing. It really, really was this belief that if you looked a little more Western [and] a little less Asian, it's like having a great degree from a better school. Or it's like having another skill. It was something to put in your portfolio."

For years, SuChin says she considered getting the surgery. She even went in for preliminary medical consultations.

While filming her documentary series, SuChin saw a woman get the eyelid surgery that she had wanted her entire life. That experience made her have a change of heart.

"Suddenly I saw it, that crease as a scar," she says. "Finally, I could accept the fact that [I] wouldn't be walking into a doctor's office."

SuChin may never have a crease in her eyelid, but she says she still uses tricks to make her eyes look bigger on camera. When she and her mom watch tapes of her MTV gigs, she says they'll make comments like, "Whoa…that was a good eye day!"

"Rather than a good hair day, I have good eye days or bad eye days," she says.

Like many teenagers, SuChin has insecurities about her looks, but she has learned to love herself. "I still feel beautiful without the crease," she says. "Somewhere deep inside, it's struggling free."

"Suddenly I saw it, that crease as a scar," she says. "Finally, I could accept the fact that [I] wouldn't be walking into a doctor's office."

SuChin may never have a crease in her eyelid, but she says she still uses tricks to make her eyes look bigger on camera. When she and her mom watch tapes of her MTV gigs, she says they'll make comments like, "Whoa…that was a good eye day!"

"Rather than a good hair day, I have good eye days or bad eye days," she says.

Like many teenagers, SuChin has insecurities about her looks, but she has learned to love herself. "I still feel beautiful without the crease," she says. "Somewhere deep inside, it's struggling free."

Low self-esteem and insecurities have been troubling teens for far too long. Oprah wants young women of all races to begin talking about what makes them beautiful. That's why she's launching the O Girl, O Beautiful campaign!

Oprah is asking teens to commit to this program for one year. To get involved, start by downloading a contract and pledge to write down at least one thing about yourself that makes you special, every day.

Print and sign your contract.

Print and sign your contract.

"What I know for sure is that you really don't become what you want. You become what you believe," Oprah says. "The real key is focusing on what you really like about yourself. When you focus on what you like, you begin to see that you like even more things."

Oprah is asking teens to commit to this program for one year. To get involved, start by downloading a contract and pledge to write down at least one thing about yourself that makes you special, every day.

"What I know for sure is that you really don't become what you want. You become what you believe," Oprah says. "The real key is focusing on what you really like about yourself. When you focus on what you like, you begin to see that you like even more things."

Published 01/01/2006