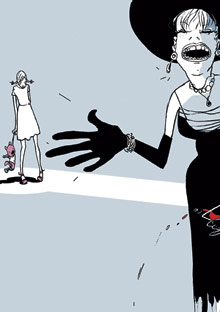

Illustration: Istvan Banyai

It's usually about nurturing her child—not swilling vodka, hitting on her daughter's boyfriends, and setting her up with frat boys by stranding her at the bar. A daughter relives her stormy relationship with her mother and the way she finally found the calm within it.

Lots of daughters have difficult mothers. I knew that. So I didn't spend a lot of time questioning my own mother's eccentricities. The Thanksgiving I went to stay with her and my stepfather, Butch, at their Florida vacation condo, for instance, I was only hoping the change of scenery might distract her from her usual mission of trying to get it through my head just how much I was screwing up my life. Instead my mother directed Butch to drive straight from the airport to a noisy college bar. She ordered a double vodka and struck up a conversation with the baseball-capped frat boys at the next table. “They're nice! And good-lookin', too!” she shouted across the table at me. “Why don't you move over here by me and talk to them? You're not going to get a boyfriend sitting there waiting for Prince Charming to find you!”

“Mom,” I feebly protested. “They're too young for me.”

“Bullshit!” she declared and launched into a boilerplate tirade, which might have been titled “Why You Are a Dumb-ass Who Wouldn't Know an Eligible Bachelor If He Hit You on the Head with a Dead Polecat.”

My mother never met an adult male I wouldn't have been better off marrying rather than doing whatever it was I thought I was doing up in New York. I excused myself to go to the ladies' room. I'd sat through the speech. All I had to do now was sit through a plate of chicken wings and some nachos.

When I came back, my mother and Butch weren't at the table. I looked around. They weren't anywhere in the restaurant.

One of the frat boys leaned over and said, “Your mother said she had to go. She asked if we'd give you a ride home.”

My mother was right about one thing. The frat boys were nice. But I had only a vague notion of where “home” was (I'd visited the condo briefly once before) and had no phone number or address. I sat in on the boys' night out for hours, feeling as though there was a large rock in my rib cage, trying to let them carry on the kind of conversations 20-year-old guys usually have, instead of the kind they have when an older woman has been foisted upon them by her mother. Sometime much later, a couple of them drove me around for an hour or so, until eventually a road looked familiar, and then another road, and then another.

The next day, my mother greeted me with a cheery “Did you have fun?” With all the gumption I could muster, I said, “Not really.”

“Well, that doesn't surprise me,” she said. “You're not a people person like me. You're more like your daddy—as mean as a snake.” This snake business was a favorite leitmotif of Mom's. I had never thought my father was mean. It's true that I didn't spend as much time with him as with my mother (his second wife didn't much welcome my brother and me), but to my mind the man bore more resemblance to a Labrador retriever than he did to a snake.

My mother, however, is a people person—if being a people person means loving an audience. She's a flamboyant former Southern belle, Tallulah Bankhead playing the role of Carol Brady. As you'd expect, the miscasting did make for moments of comedy. My friends thought my mother was a blast, since she told dirty jokes and smoked and drank with us. The local society portrait painter—adored by my mother's country club friends for portraying them as, say, wood nymphs in paintings with titles like Starshine and Raindance—pretty much nailed our relationship: She painted my mother as the sun, smiling and surrounded by a dazzling nimbus of gold rays. I became the moon, looking wan on a blue background and draped in ghostly white. My mother hung her portrait over the mantelpiece in her living room. She hung mine on the landing of the stairs leading up to the spare bedroom.

For years I asked her advice, hoping for a word of encouragement. Instead I'd hear her say, “I always thought sending you to that college was a huge waste of money.” Boyfriend broke up with me? Must have been because I was something of a slut.

If I brought a man home, her opinion was never in doubt. Joe, for instance, returned from a trip to the bathroom a bit ruffled to report, “Your mom just grabbed me and French-kissed me.” (He was her all-time favorite.) Upon meeting Eric, she tousled his hair and told him she thought he was so cute she could just eat him up. He dumped me shortly thereafter. She got his number from directory assistance and called him up sobbing, begging him to take me back. Needless to say, I stayed dumped.

I also got a steady stream of phone calls from strange men my mother had met in bars who seemed to think I'd be dying to go out with them. Apparently, she had pressed my phone number on them, saying I desperately needed a decent man to knock some sense into me.

Once, when my mother came to visit with friends, she took me out to a nightclub where the waiters took turns lip-synching to tunes like “Rock Around the Clock” and a gargantuan fiberglass Chevrolet appeared to have just plowed through one wall. I watched her knock back cocktails and shimmy with anyone who would shimmy back.

Eventually, I left, telling her friends I was tired. She arrived home an hour later and came through the door like a jet-propelled wolverine, grabbing me and shaking me as I lay on the sofa.

“I will not tolerate your being rude to my friends!” she shrieked, eyes bulging, fingernails digging into my arms. “When I take you someplace, you stay there and have fun!” I kicked her away, and she slapped me, hard. I fled to the bathroom, locked myself in, and sat crying on the toilet. When one of my mother's friends returned a few minutes later, I heard her ask, “What's the matter with her?”

“Aw, she's just crying over some guy,” my mother said.

The next day it was as though nothing had happened. I wondered whether she even remembered it.

Why did I never just stop and think, "Wouldn't my life be more pleasant if I interacted a little less with my mother?" Why couldn't I give up expecting her to be the parent I wanted?

It never crossed my mind. I was 28 years old and had no idea why I was so unhappy. I quit my job in book publishing to try my hand as a writer, bartending for a living. But as the pitch of my mother's disapproval became ever more shrill, I couldn't seem to see the way forward. The rock that had sat in my rib cage during the night out in Florida was now a permanent fixture. I found myself choking back tears all day long.

Fortunately, in New York people never stop talking about their shrinks, so the thought finally occurred to me, "Maybe seeing a professional is a better idea than the one I had the other night about throwing myself from the window of my 12th-floor apartment."

If I brought a man home, her opinion was never in doubt. Joe, for instance, returned from a trip to the bathroom a bit ruffled to report, “Your mom just grabbed me and French-kissed me.” (He was her all-time favorite.) Upon meeting Eric, she tousled his hair and told him she thought he was so cute she could just eat him up. He dumped me shortly thereafter. She got his number from directory assistance and called him up sobbing, begging him to take me back. Needless to say, I stayed dumped.

I also got a steady stream of phone calls from strange men my mother had met in bars who seemed to think I'd be dying to go out with them. Apparently, she had pressed my phone number on them, saying I desperately needed a decent man to knock some sense into me.

Once, when my mother came to visit with friends, she took me out to a nightclub where the waiters took turns lip-synching to tunes like “Rock Around the Clock” and a gargantuan fiberglass Chevrolet appeared to have just plowed through one wall. I watched her knock back cocktails and shimmy with anyone who would shimmy back.

Eventually, I left, telling her friends I was tired. She arrived home an hour later and came through the door like a jet-propelled wolverine, grabbing me and shaking me as I lay on the sofa.

“I will not tolerate your being rude to my friends!” she shrieked, eyes bulging, fingernails digging into my arms. “When I take you someplace, you stay there and have fun!” I kicked her away, and she slapped me, hard. I fled to the bathroom, locked myself in, and sat crying on the toilet. When one of my mother's friends returned a few minutes later, I heard her ask, “What's the matter with her?”

“Aw, she's just crying over some guy,” my mother said.

The next day it was as though nothing had happened. I wondered whether she even remembered it.

Why did I never just stop and think, "Wouldn't my life be more pleasant if I interacted a little less with my mother?" Why couldn't I give up expecting her to be the parent I wanted?

It never crossed my mind. I was 28 years old and had no idea why I was so unhappy. I quit my job in book publishing to try my hand as a writer, bartending for a living. But as the pitch of my mother's disapproval became ever more shrill, I couldn't seem to see the way forward. The rock that had sat in my rib cage during the night out in Florida was now a permanent fixture. I found myself choking back tears all day long.

Fortunately, in New York people never stop talking about their shrinks, so the thought finally occurred to me, "Maybe seeing a professional is a better idea than the one I had the other night about throwing myself from the window of my 12th-floor apartment."

After a year or so in therapy, I started to think that I could handle my mother a little differently. I continued to put myself in the line of fire, but now I fought back. For a while it just made things harder. I would end up in tears, ground down by my mother's viciousness. “You are a worthless piece of shit!” she'd yell through the phone. “I'm doing you a favor. You need to be broken! You need to hit rock bottom.”

I said some horrible things, too. I told her she'd never done anything for me except to sleep with my father (and I phrased it a little more forcefully). I sleepwalked through my days, consumed by hatred. I lay in bed at night entertaining myself with visions of my mother being squashed by a falling baby grand or mown down by a crosstown bus.

One night I did hit rock bottom, if not in the way my mother had meant. She was telling me what a failure I was, that I'd never amount to anything. Suddenly, I found myself screaming into the phone, “Mother! I'm not you! I'm a separate person! I have my own life, and it doesn't matter what you think of it!” I remember a silence at the other end of the line. From that moment, I saw that I had never really thought of myself as me—I had only been a blank screen, the moon feebly throwing off a pale (and entirely unsatisfactory) imitation of her personality.

I hardly spoke to her on the phone after that. I stopped asking her advice, and at holidays I made the decision—why had I not done it sooner?—to stay at my father's house. I'd always known that my mother qualified as a serious drinker, but now I realized she was suffering from a clinical condition. And that it was her problem, not mine.

The changes seemed to bewilder my mother. I knew something had shifted between us when I took a boyfriend home and he laughed at my mother's four-letter words and sozzled escapades as you would at any harmless eccentric. And she didn't lay a finger on him.

I married that boyfriend, and we had children of our own. We literally distanced ourselves from my mother by moving thousands of miles away. It seemed, finally, as if I had figured things out.

Except motherhood didn't come easy to me. Listening to my daughter cry for hours as an infant or trying to handle her defiance as a toddler was too much for me at times. I'd suddenly snap and start screaming like a madwoman at my little girl, clutching her by the arms as I shrieked. My husband would say, “Everyone loses their temper with their children from time to time.” But I remembered similar scenes from my own childhood. I couldn't believe that after all that effort to become myself, as a mother I was back to reflecting her.

I said some horrible things, too. I told her she'd never done anything for me except to sleep with my father (and I phrased it a little more forcefully). I sleepwalked through my days, consumed by hatred. I lay in bed at night entertaining myself with visions of my mother being squashed by a falling baby grand or mown down by a crosstown bus.

One night I did hit rock bottom, if not in the way my mother had meant. She was telling me what a failure I was, that I'd never amount to anything. Suddenly, I found myself screaming into the phone, “Mother! I'm not you! I'm a separate person! I have my own life, and it doesn't matter what you think of it!” I remember a silence at the other end of the line. From that moment, I saw that I had never really thought of myself as me—I had only been a blank screen, the moon feebly throwing off a pale (and entirely unsatisfactory) imitation of her personality.

I hardly spoke to her on the phone after that. I stopped asking her advice, and at holidays I made the decision—why had I not done it sooner?—to stay at my father's house. I'd always known that my mother qualified as a serious drinker, but now I realized she was suffering from a clinical condition. And that it was her problem, not mine.

The changes seemed to bewilder my mother. I knew something had shifted between us when I took a boyfriend home and he laughed at my mother's four-letter words and sozzled escapades as you would at any harmless eccentric. And she didn't lay a finger on him.

I married that boyfriend, and we had children of our own. We literally distanced ourselves from my mother by moving thousands of miles away. It seemed, finally, as if I had figured things out.

Except motherhood didn't come easy to me. Listening to my daughter cry for hours as an infant or trying to handle her defiance as a toddler was too much for me at times. I'd suddenly snap and start screaming like a madwoman at my little girl, clutching her by the arms as I shrieked. My husband would say, “Everyone loses their temper with their children from time to time.” But I remembered similar scenes from my own childhood. I couldn't believe that after all that effort to become myself, as a mother I was back to reflecting her.

That was a terrifying time, to be at home with a small child, knowing I wasn't keeping it together. After another round of therapy, I saw that separating myself from my mother wasn't enough. I needed to try to understand her. Her own mother, I recalled, had been an alcoholic, and, faced with my own failures as a parent, I saw that she must suffer from the same shaky sense of self I had.

I knew that some women were able to fix their relationships with their difficult mothers—but I also knew that was impossible for me. I'd met people who, like me, had decided that cutting their mothers out of their lives was for the best. But that hadn't worked, either.

Now I'm trying a third way: I don't depend on my mother for support or encouragement, but I no longer spend time or energy pushing her away. We talk about once a month for no more than ten minutes. She tells me tidbits of hometown gossip—mostly thrilling anecdotes about bridge tournaments and the gall-bladder surgery of people I've never met—and I tell her cute things her grandchildren have done. She comes for a visit once a year, and maybe because I have a little more of the emotional distance I always needed, I don't feel the impulse to duck and cover the moment she rings the doorbell.

I look at my children, and I'm glad they know their grandmother, especially since with them her famous sense of fun comes into its own. On her last visit, she unzipped her bulging suitcase to reveal a mountain of pink tulle, feathers, and sequins with which she planned to fashion a to-die-for fairy costume. Underneath she'd managed to squeeze in a rocking horse—she'd only had to dismantle it and cut up the insides of the suitcase a bit to get it to fit, she explained. I couldn't help noticing she'd also packed a handy thermos full of vodka, but she had the kids, like my erstwhile teenage friends, in hysterics. In fact, we all laughed.