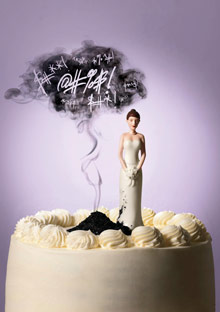

Illustration: Reena de la Rosa

When is a marriage troubled, and when is it fatally flawed? One woman looks back on her husband's temper—and their journey to a more perfect union.

I was sitting at the wine bar with a friend—I'll call her Lacey—who was considering divorcing her second husband, having recently discovered his stash of hard-core porn. "I know that no man's a saint," she said, "but I can't live with lechery.""That takes care of lust," I thought, and made a mental note. Although I hadn't told Lacey, I had a little project going—involving a question I'd been challenging other friends to answer: Given that no person and no marriage is perfect, if you could pick your mate's flaw—the one flaw you could live with—what would it be? Nothing so slight as socks on the floor or a residual jones for Pac-Man. I meant the things we keep hidden from even our closest confidants, the things that can prove fatal to a marriage: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, envy, wrath, and pride. So far, none of my friends had been able to pick a "best" flaw; all they'd managed to do was rule out the worst.

"I'd rather die," willowy Meg had said, "than be married to a glutton."

Greed? "Cross it off," Theresa snapped, then hesitated when I suggested pride. "Pride is why my husband left me," she said. "I could never admit I was wrong."

Now, at the wine bar, Lacey sipped and sighed. "I want a husband like yours," she told me. "Someone who reads me love poems over breakfast."

I just smiled. After 26 years, Bob and I do still spend summer days as we did the July we got married: camping along Northwest rivers, fly-fishing, drinking Champagne. The demands of our professional lives (both of us are writers and teachers), the rigors of child rearing, the empty nest we are fluffing, cross-country moves, money woes—the pressures that so often destroy a marriage, ours has survived. To Lacey, it seemed a storybook romance. What she didn't know was how close I had come to leaving the marriage she idealized. I'd never told her the flaw I'd chosen—that Bob was a wrathful man.

When I met Bob, I was 22. He was seven years older, seven inches taller, and I was enthralled by his intellect, his passion, his hair (oh, his hair! dark, thick like an animal's fur, hanging down in his eyes, curling at his collar…). He'd sung in a rock band, been a conscientious objector during Vietnam, and was now a talented poet and teacher. I watched him weep over the death of John Lennon and rail against wrong-minded politicians. And soon after we moved in together, I got my first glimpse of his rage.

The lawn sprinkler that failed to oscillate? Bob beat it into the ground, gaskets flying. The chain saw that wouldn't run, he pitched against a tree until it snapped into pieces. I laughed when I recounted these slapstick incidents to friends. Who was he hurting, after all?

I was 25 when Bob asked me to marry him. Moderate in his consumption, balanced in his ambition, kind to my parents, and lustful only for me: If an occasional temper tantrum was his only flaw, I should count myself lucky.

But one afternoon the summer we married, Bob and I were driving back from the store when we found ourselves behind an elderly woman at a traffic light. She hesitated, not sure if she wanted to turn left or right. Bob grimly rode her bumper. "Get off the road, you old bag!" As we roared by, he flipped her off; on her face was a mix of befuddlement and fear.

I sat stunned. Outraged.Speechless. Silently fuming.

"What's wrong?" Bob asked, truly curious.

It wasn't right, I said, how he had treated that woman.

"But she couldn't hear me."

"But I could." I held my hand to my heart. "And it hurt."

Over the next year, Bob's outbursts became more frequent, until one morning, in the middle of an argument whose subject neither of us remembers, he picked up the wooden table at which we were eating breakfast and brought it down so hard it shattered. I backed to the wall. Mouth twisted, Bob grabbed my arms. "Why are you making me do this?" he said through clenched teeth. I shook my head, unable to make sense of the question, afraid to attempt an answer.

Trying to talk it out only made things worse. Bob insisted that I was the one being unreasonable. I'd never seen anyone so enraged, but now I wondered: Were my expectations unfair? I'd been raised in a family of stoics, after all, and my upbringing was defined by suppressed emotion. But surely I had enough objectivity, enough perspective, to know that busting out a window with your bare knuckles—or kicking a hole in a wall, or denting the car hood with your fist—wasn't standard behavior. And I was beginning to fear that he might turn his rage on me.

I wanted to tell someone about Bob's anger, so someone could tell me what I should do. But who could I tell, and how would I? My friends and family loved Bob for the same reasons I did: his wit, his honesty, his compassion, his loyalty. And those same people had an equally firm sense of me: that I was a strong-minded woman who would never allow herself to be intimidated. Safer to remain silent than to risk their judgment and doubt. "It will get better," I assured myself. What I really meant, though, was "I will get better." If Bob's paying the bills incited a loud invective against the obscenity of money, then I would pay the bills. If raising my voice brought out the bully in him, then I would keep my mouth shut.

A few months after our fourth anniversary, our daughter was born; her brother, two years later. Raising children raised the stakes. Waiting in line at a McDonald's drive-through made Bob furious. His rage was like a sudden squall—I spent my energy keeping his anger from swamping us all. Our children sometimes laughed at his tirades, sometimes cowered, and as they grew into adolescents, they often rolled their eyes—even as I worked to hide my increasing fear that I was staying in a marriage I was simply too proud to leave. Torn between self-doubt and shame, I kept on keeping my secret, though I still longed for someone to tell me: How would I know when it had gone too far?

The answer came one day as Bob and I were driving down the highway to the hardware store. I was fretting, imagining the minor mishap that would turn our little jaunt into hell on wheels (a flat tire, someone's badly parked car, an inept clerk), and wondering aloud if I should have just stayed home. I had become that little old woman at the light, unsure of which way to turn.

Suddenly Bob hit the brakes, cranked a U-turn, and brought us to a sliding stop, cursing my indecision so cruelly that I sat paralyzed, afraid he might gun the car back onto the highway.

Back home, I gave him an ultimatum: See a counselor, or our marriage was over.

And maybe this is the difference between a flaw and a fatal flaw. Even though it meant exposing his failures, Bob chose to keep our marriage alive. We made appointments separately and together. Talking to the therapist filled me with dread: dread that the problem was not Bob's temper but my own prideful expectations; dread that I was betraying him; dread that I had allowed myself to be victimized; dread that we were broken and couldn't be fixed.

"You can save this marriage," the therapist told us, "but you've got to understand what's causing the problem." She explained that when caught in conflict, the brain releases adrenaline and cortisol, inducing the fight-or-flight response. Never one to turn tail and run, Bob chose to bully the world into submission. But when I was the one who defied him, he felt the conflict as rejection. His terror then led him to rage at the very person he feared losing: me.

It wasn't easy for Bob to accept that the anger that puffed him with strength was a shield against vulnerability, or that each act of physical and verbal violence was an indirect threat against me.

Along with assigned readings and exercises, the therapist gave Bob a palm-sized thermometer. "When you rage," she said, "blood is diverted from your extremities to your vital organs, and your fingers turn cold. Count to ten. Focus on calming down, letting your hands warm up by degrees. Make it a habit. Practice."

It's been more than a decade since that initial appointment. At first, when his temper flared, Bob would grasp the thermometer, take a deep breath. "I'm getting better, aren't I?" he'd ask, and he was. He discovered other ways to engage his daily frustrations: taking long walks, imagining that the driver in front of him was someone he loved, remembering that he wanted nothing in the world to frighten me, least of all him.

My change, too, came by degrees, first by revealing Bob's rages to the therapist and then to a few close friends. "There's so much good in Bob," some of them told me. "He wants to do better. That's what makes the difference." Another friend said, "I'd have left him years ago." Later she would confess that she, too, was given to rages, a secret shame that made her sure she could never be wholly loved.

And so, as I sat in the wine bar, listening to Lacey mourn the impending loss of her second marriage, I posed my query, reminding her that she'd already eliminated lust. She twirled the glass in her fingers. "Not pride," she finally said. "My first husband hid his debt and drove us into bankruptcy. I didn't know until I got the call from the attorney. We lost everything. I couldn't live with the betrayal."

"You never told me that," I said.

"I never told anyone."

I've come to realize that you never know the secrets of someone else's marriage—but that when it comes to your own, it's better to break the silence before the silence breaks you. I couldn't hear the truth until I gave it voice, and neither could Bob. By reaching out for help, we chose to leave the isolated island of shame and blame and hitch ourselves to something truer than a perfect marriage: a union defined by our desire to grow beyond our flaws. Today Bob's rages are a thing of the past, the occasional tremors like the fading aftershocks of an earthquake (and my zero-tolerance policy proof of my own shored-up foundation). Still, when Lacey turned the tables on me—"What flaw would you choose?"—I didn't give it a second thought.

"Anything but wrath."

And then I told her why. What I saw in her face was disappointment and relief: My marriage wasn't so perfect after all, yet somehow it had survived. Could she, should she allow her soon-to-be ex a chance to redeem himself?

I didn't have an answer, only an ear.

Keep Reading

Kim Barnes' most recent novel, A Country Called Home, has just been released in paperback (Anchor).