Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

Vernetta Cockerham did everything by the book. She took her abusive husband to court. Got a protective order. Reported his violations to the police. Yet in the end, none of that was enough to prevent the worst tragedy she could imagine. Why aren't the laws against domestic violence enforced?

Vernetta Cockerham woke up on November 19, 2002, feeling at peace for the first time since she could remember. After months of living in terror of her estranged husband's violence, knowing he would kill her if he could, she'd gone to sleep the night before relieved beyond words by the thought of his finally being arrested. Today she could fully focus on her children. Her oldest, Candice, had an appointment with an army recruiter. Cockerham was so proud of her daughter, the way she made friends easily even though she was one of the few African-American students in her rural North Carolina high school. And now, at 17, Candice wanted to serve her country. Cockerham loaded her three kids into the Explorer and dropped off 6-year-old Rashieq at school, just down the street from where they lived. Their home, an old yellow farmhouse, had belonged to her grandmother and stood right in the center of Jonesville, within plain view of the town hall and the police station.

She drove the baby, Dominiq, almost 9 months old, to daycare, then left Candice at the library to copy a few documents for her interview. Cockerham had one more stop that morning. She needed to call the department of social services because someone—and she was sure it was her husband—had filed an anonymous child-neglect complaint against her. That man would stop at nothing. But at least now that he was in jail, he wouldn't be showing up everywhere she went to slam her around and threaten her, or digging holes near the house and telling her they would be the family's graves. She made the call from a friend's place and went back to the library. But Candice had already headed home.

As Cockerham pulled up to the house, she noticed the front door—it wasn't like her daughter to leave it ajar that way, especially with all that had been going on.

And then in a horrifying instant she saw them: her husband's keys, dangling in the lock.

She was barely through the door when he lunged at her with a knife.

"I killed her," she heard him say as if in slow motion. "And I'm going to kill you."

She reached for the knife, grabbing it by the blade.

There was no pain. Only terror.

"Candice!" she screamed. "Candice!"

He lunged again and Cockerham took cover behind a heavy three-tiered plant stand. It toppled, the glass shelves crashing and knocking the knife from her husband's hand. She felt a shard of glass slice into her head and the warmth of her blood dripping down her back. Just before she blacked out, she felt his hands around her throat.

When Cockerham came to, she thought she heard Candice's voice calling for her, as if rousing her from a deep sleep.

"Ma, get up. Get up."

Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

But she didn't see her daughter anywhere. The front door was closed now, and as Cockerham struggled with the dead bolt, she caught sight of her fingers—cut so badly, bone showed through the flesh. The lock gave and Cockerham ran, stumbling in the morning chill, across the street and through the vacant lot facing her house to the police station. There she collapsed in the doorway, her throat slashed and bleeding heavily. Drifting in and out of consciousness, she pleaded for someone to help her daughter. Chief Robbie Coe held a towel to her neck, trying to stanch the bleeding. "I know who did it, but you need to tell me who did it," he told her. But Cockerham had only one thing on her mind: Where are my kids?

Coe sent two officers, Scotty Vestal and Tim Lee Gwyn, to the house, where they waited for backup. Another officer found Candice's body in the downstairs bedroom. Heavy duct tape covered her mouth and nose. She'd been beaten and suffocated; an electrical cord was tied around her neck and reinforced with a layer of tape. Her hands and feet had been bound. And her jeans were pulled down around her knees, leaving her half naked.

The police had not arrested Cockerham's husband, Richard Ellerbee. And despite everything she'd done to protect herself and her family from a crime like this, the unbearable tragedy had happened anyway. "It was absolute torture what he did," she says.

Like every state, North Carolina has stringent laws to protect women and their children from domestic violence. The process often begins with a woman filing for an emergency protective order, which can be obtained without a lawyer from a local court (it requires filling out paperwork and is usually issued by a judge on the strength of the complaint). Protective orders (also called restraining orders) vary from state to state but typically forbid an abusive partner to come within a certain distance of the victim and may make other restrictions, like prohibiting phone calls or e-mail. In North Carolina, the emergency order remains in effect until a hearing takes place (usually within ten days), at which time both sides are allowed to present evidence. The judge then decides whether to grant a final order, which lasts up to a year.

If police find probable cause that an order has been violated—even something as simple as driving past the victim's house—most states have laws that call for an arrest. However, a study published in 2000 in Criminal Justice and Behavior, based on Massachusetts records and studies in other states, suggests that as many as 60 to 80 percent of restraining orders are not enforced. Furthermore, a 2000 U.S. Department of Justice study found that officers made arrests in only 47 percent of cases in which the victim reported being raped—even fewer when the complaint was assault (36 percent) or stalking (29 percent). In California a 2005 report by the state attorney general's office found widespread hesitation among police and prosecutors to enforce restraining orders—with dangerous consequences. "For the victim," the report concluded, "there is a loss of faith in the system and reluctance to report new violations, even as these violations grow in seriousness. For the batterer, there is a sense of empowerment to commit new violations and more violent crimes." When the rules call for mandatory arrest, says Kristian Miccio, an associate professor of criminal law and procedure at the University of Denver's Sturm College of Law, "and they don't enforce it, you have the illusion of protection, which is worse than not having it at all."

Coe sent two officers, Scotty Vestal and Tim Lee Gwyn, to the house, where they waited for backup. Another officer found Candice's body in the downstairs bedroom. Heavy duct tape covered her mouth and nose. She'd been beaten and suffocated; an electrical cord was tied around her neck and reinforced with a layer of tape. Her hands and feet had been bound. And her jeans were pulled down around her knees, leaving her half naked.

The police had not arrested Cockerham's husband, Richard Ellerbee. And despite everything she'd done to protect herself and her family from a crime like this, the unbearable tragedy had happened anyway. "It was absolute torture what he did," she says.

Like every state, North Carolina has stringent laws to protect women and their children from domestic violence. The process often begins with a woman filing for an emergency protective order, which can be obtained without a lawyer from a local court (it requires filling out paperwork and is usually issued by a judge on the strength of the complaint). Protective orders (also called restraining orders) vary from state to state but typically forbid an abusive partner to come within a certain distance of the victim and may make other restrictions, like prohibiting phone calls or e-mail. In North Carolina, the emergency order remains in effect until a hearing takes place (usually within ten days), at which time both sides are allowed to present evidence. The judge then decides whether to grant a final order, which lasts up to a year.

If police find probable cause that an order has been violated—even something as simple as driving past the victim's house—most states have laws that call for an arrest. However, a study published in 2000 in Criminal Justice and Behavior, based on Massachusetts records and studies in other states, suggests that as many as 60 to 80 percent of restraining orders are not enforced. Furthermore, a 2000 U.S. Department of Justice study found that officers made arrests in only 47 percent of cases in which the victim reported being raped—even fewer when the complaint was assault (36 percent) or stalking (29 percent). In California a 2005 report by the state attorney general's office found widespread hesitation among police and prosecutors to enforce restraining orders—with dangerous consequences. "For the victim," the report concluded, "there is a loss of faith in the system and reluctance to report new violations, even as these violations grow in seriousness. For the batterer, there is a sense of empowerment to commit new violations and more violent crimes." When the rules call for mandatory arrest, says Kristian Miccio, an associate professor of criminal law and procedure at the University of Denver's Sturm College of Law, "and they don't enforce it, you have the illusion of protection, which is worse than not having it at all."

Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

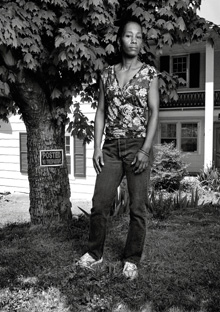

Vernetta Cockerham is living that painful truth. When she took out a protective order against her husband in October 2002, she believed fully in the power of the law to keep her safe. And repeatedly she reported Ellerbee's violations to the police. But even when they arrested him, he was released on bond. "I go over it every day," she says, "and every day I say to myself, 'You did everything you were supposed to do by law.'"

Now she's trying to change the system. On November 18, 2004, almost exactly two years after Candice's murder and her own near death, Cockerham sued the town of Jonesville and its police department for failing to enforce the restraining order that was in place to protect them. It's been an exhausting five-year legal battle, and the case has not yet gone to trial*, leaving some of the facts in dispute—including the promise she says the police made to arrest her husband the night before the bloodshed. Cockerham's resolve is steely, but when she describes the crowd of teenagers who lined the street for Candice's funeral, she still breaks down and weeps.

Cockerham is a slender woman with high cheekbones, a wide smile, and today, a thick scar that runs down the left side of her neck, from jaw to collarbone. Despite what she's been through, she laughs easily and walks with a skip in her step. At 40, she could easily pass for 25.

She was born in 1969 in Paterson, New Jersey, the youngest of three girls. Her paternal grandmother, Marie Edmonds, stepped in early to raise the sisters because their parents were unable to provide a stable home. When it was time for Cockerham to go to school, her grandmother moved the children to her home in Jonesville, a town of about 1,500 in the northwest corner of North Carolina. The family could trace its roots there at least five generations back. Just about every other house on their winding street belonged to an aunt, uncle, or distant cousin.

Edmonds worked the third shift at a nursing home and raised her grandchildren the old-fashioned way. She canned vegetables, washed clothes by hand, made sure everyone went to church on Sundays. And she taught Cockerham how to fend for herself.

When Cockerham turned 14, she moved to Newark, New Jersey, hoping to get to know her mother; then she went to live in Paterson with her father and enrolled in high school. The summer before her sophomore year, she became a math tutor, and one of her students was a linebacker named Kevin Baker. He was three years older, almost 18, but he and Cockerham fell for each other. By the middle of that school year, she was pregnant.

After having the baby—Candice—in Jonesville, Cockerham joined Baker in Paterson and married him. His sister was dating a family friend, a hardworking carpenter named Richard Ellerbee. It was Ellerbee who told Cockerham that her husband was cheating on her. Grateful to Ellerbee, 13 years her senior, for letting her know, she soon found herself confiding in him.

Cockerham and Baker divorced. She finished school and got a job in the records room of the Paterson Police Department. But when Candice was 6, Cockerham decided she'd rather raise her daughter in Jonesville. Back home, she found her own place, and juggled two jobs. She had the early-morning shift at a Shoney's restaurant, bringing Candice with her when she opened the place at 4:30 A.M., then taking her to school during her break. When that shift was over, she'd go work at a state prison near Yadkinville, about a half hour away.

Now she's trying to change the system. On November 18, 2004, almost exactly two years after Candice's murder and her own near death, Cockerham sued the town of Jonesville and its police department for failing to enforce the restraining order that was in place to protect them. It's been an exhausting five-year legal battle, and the case has not yet gone to trial*, leaving some of the facts in dispute—including the promise she says the police made to arrest her husband the night before the bloodshed. Cockerham's resolve is steely, but when she describes the crowd of teenagers who lined the street for Candice's funeral, she still breaks down and weeps.

Cockerham is a slender woman with high cheekbones, a wide smile, and today, a thick scar that runs down the left side of her neck, from jaw to collarbone. Despite what she's been through, she laughs easily and walks with a skip in her step. At 40, she could easily pass for 25.

She was born in 1969 in Paterson, New Jersey, the youngest of three girls. Her paternal grandmother, Marie Edmonds, stepped in early to raise the sisters because their parents were unable to provide a stable home. When it was time for Cockerham to go to school, her grandmother moved the children to her home in Jonesville, a town of about 1,500 in the northwest corner of North Carolina. The family could trace its roots there at least five generations back. Just about every other house on their winding street belonged to an aunt, uncle, or distant cousin.

Edmonds worked the third shift at a nursing home and raised her grandchildren the old-fashioned way. She canned vegetables, washed clothes by hand, made sure everyone went to church on Sundays. And she taught Cockerham how to fend for herself.

When Cockerham turned 14, she moved to Newark, New Jersey, hoping to get to know her mother; then she went to live in Paterson with her father and enrolled in high school. The summer before her sophomore year, she became a math tutor, and one of her students was a linebacker named Kevin Baker. He was three years older, almost 18, but he and Cockerham fell for each other. By the middle of that school year, she was pregnant.

After having the baby—Candice—in Jonesville, Cockerham joined Baker in Paterson and married him. His sister was dating a family friend, a hardworking carpenter named Richard Ellerbee. It was Ellerbee who told Cockerham that her husband was cheating on her. Grateful to Ellerbee, 13 years her senior, for letting her know, she soon found herself confiding in him.

Cockerham and Baker divorced. She finished school and got a job in the records room of the Paterson Police Department. But when Candice was 6, Cockerham decided she'd rather raise her daughter in Jonesville. Back home, she found her own place, and juggled two jobs. She had the early-morning shift at a Shoney's restaurant, bringing Candice with her when she opened the place at 4:30 A.M., then taking her to school during her break. When that shift was over, she'd go work at a state prison near Yadkinville, about a half hour away.

Ellerbee kept in touch with her, and in 1993, when Cockerham was 24, he called. He was desperate to leave Paterson. Could he visit? Soon enough he was job-hunting in Jonesville and making plans to settle there. She found that she liked having him around.

It's hard to say when their love, if that's what it was, tipped into something dark and frightening. At first she felt needed, and that appealed to her. But soon she started noticing he didn't like being told what to do. She also noticed how controlling he was. "Having to ask him, not tell him, what I was doing," she says, "became an issue for me."

Cockerham never wanted children with Ellerbee. After a difficult birth with Candice, she believed she couldn't conceive again, but in 1995 she found herself pregnant with Rashieq, who was born in May of the following year. Around that time, she says, she tried to pull back from a sexual relationship with Ellerbee. But he was a large, heavy man, more than six feet tall, and at 57 and only 140 pounds, she was unable to stop him from doing as he pleased. "I didn't know what to do," she says. "It was as if the more I drew myself away, the more aggressive he would become."

Feeling miserable and trapped, she threw herself into her church. "It'll work out," her grandmother assured her. "And you got to do right by the kids." In August 1999, however, during a routine argument, Ellerbee grabbed her purse, hit her in the face with an open hand, choked her, and threw her to the ground. Cockerham got a protective order, but after he threatened her, she dropped it.

By the summer of 2001 she was pregnant with her third child, and Ellerbee insisted that they marry. Her pastor, who had counseled the couple, was wary of Ellerbee's interest in her assets and refused to conduct the ceremony. Cockerham hoped Ellerbee would drop the idea. But one day he offered to drive her to the grocery store, and headed toward the county courthouse instead. They were married there December 1, 2001. "I knew something wasn't right, but I did not know how to get out of it," Cockerham recalls. "I just wanted the family life to work. I wanted the father figure. I wanted the normalcy." During the ceremony, she says, "I cried the entire time. I never said a word. He spoke for me."

Dominiq was born February 26, 2002, and by summer Cockerham found herself always on edge, waiting for her husband to explode. On the Fourth of July, he did. Cockerham had packed a picnic for the family and piled the baby's stroller and other belongings by the front door.

"I'm not going," Ellerbee said.

"What do you mean?"

Instead of arguing in front of the kids, they went outside and sat in his silver Chevy Blazer. As they continued fighting, she saw him glance at Rashieq's baseball bat in the backseat.

"I know you're not going to hit me with that baseball bat," she said.

He reached behind him, grabbed the bat, and swung, hitting her on the back of her head. As much as it hurt, at least the children hadn't seen their father strike her. Ellerbee walked back into the house. Worried he might do something to the kids, Cockerham followed him through the door and up the stairs, motioning to Candice to get the boys outside. When Cockerham reached the second floor, her husband threw her onto the bed and held a pillow over her face.

"I'm your God," he said, his voice so smooth it terrified her, "and I can take your breath away when I get ready."

It was her breaking point.

That night, the police came and arrested Ellerbee, charging him with felony assault with a deadly weapon. Released on a $1,000 bond, he moved out of the house, at some point getting a room at the Holiday Inn off the interstate near the outskirts of town.

For Cockerham, having Ellerbee gone was almost worse than having him at home, because she never knew where he was or when he would turn up. All summer he followed her around town. He'd call and leave her messages. "I saw you at the Food Lion," he'd say, only to delete the message remotely with the codes he still had to the voice mail. He tampered with the fuse box and the gas tank outside the house. He left more messages.

In September Ellerbee pleaded guilty to reduced charges of misdemeanor assault with a deadly weapon and assault on a female and was put on three-year probation, on the condition that he not harm or threaten Cockerham. She agreed to the reduced charges because she didn't think the felony would stick—a view shared by Chad Brown, the assistant district attorney in Yadkin County who prosecuted the case. Brown thought the probation, which required Ellerbee to go to jail for 120 days if he harassed or hurt Cockerham again, would be strong enough to keep her and her children safe. The judge, Mitchell McLean, made a point of asking the clerk to note on the docket sheet that if Ellerbee violated his probation, McLean wanted to hear the case himself.

But the stalking continued. Cockerham couldn't sleep. She couldn't eat. She called the police, the sheriff, her domestic violence caseworkers. At the same time, Ellerbee also began complaining about his wife showing up at his house. "She came in a couple of times. He came in a couple of times," says Jonesville police chief Robbie Coe, who left the department in 2004. "It appeared to be a normal domestic situation, just fussing back and forth."

Most days Cockerham would check in with the Weyerhaeuser lumber plant where Ellerbee worked to make sure he was there and it was safe to leave the house. She started carrying a nine-millimeter pistol her father had given her years earlier. But as the weeks turned into months, she only felt more afraid.

One day in October, she was at the local phone company when he showed up and yelled across the parking lot, "I'm gonna get you. I will kill you before this is all over."

Again, she went to the authorities. On October 10, Ellerbee was charged with communicating threats, but as before, released on a $1,000 bond. Cockerham knew the laws by now, and took out an emergency protective order. This time she meant business. On top of the conditions for his probation, Ellerbee was ordered to stay away from the children's school and daycare center, and keep a 250-foot distance from Cockerham. "The defendant shall not assault, threaten, abuse, follow, harass (by telephone, visiting the home or workplace, or other means), or interfere with the plaintiff," the order read. "A law enforcement officer shall arrest the defendant if the officer has probable cause to believe the defendant has violated this provision."

Cockerham got a job as an assistant manager at the Quiznos sub shop in Elkin, a town across the Yadkin River, in the next county. The order applied there, too, but on November 2, Ellerbee showed up during her shift. Through the window, she could see him pacing, motioning to her to come outside. Cockerham called the Elkin police, but they didn't have a copy of her protective order—nor could she find hers, which she thought she'd put in the car—and they said there was nothing they could do. Not wanting to endanger the others in the shop, Cockerham went out to meet her husband.

He grabbed her by the shoulder, half dragged her to her Explorer, and demanded that she drive him to the one-story brick house he'd rented in Elkin. Terrified, she got into the car. He kept his hand on the steering wheel the whole time, telling her where to turn. At the house, Cockerham screamed at the top of her lungs for help, but no one responded. Ellerbee opened her car door and tried to pull her out. Cockerham took her chance, reached for the pistol under the seat, and hit him on the forehead, hard, with the butt end. But he snatched the gun, she says, threw it on the pavement, then yanked her from the car. After wrestling her to the ground, he slammed her head against the gravel and dirt. Cockerham heard him call the police from his cell phone.

He had set her up perfectly. She was at his house, with her Explorer, and she had a gun. That day Cockerham was charged with assault, while Ellerbee went free. She spent the weekend in jail, with her hair and bits of gravel matted to a throbbing wound on her forehead.

Monday morning, Tom Langan, an assistant district attorney in Surry County, which has jurisdiction in Elkin, took one look at the wound on Cockerham's forehead and knew right away that police had charged the wrong person. He was furious. "In speaking to her, it became obvious to me that she was the victim," Langan says. "This did not seem like something that would go away unless someone went to prison for a long time. Or someone died."

In 1994 Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act, which set aside more than $300 million last year for training law enforcement and victims' services. And to some extent, the effort has been successful. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the number of women killed by their boyfriends, husbands, or ex-husbands dropped by almost 26 percent (from 1,587 to 1,181) between 1976 and 2005, the last year for which there are statistics, while the number of men killed by intimate partners fell by 75 percent (to 329). Nevertheless, the Justice Department today estimates that more than 1.8 million women a year are raped, assaulted, or stalked by an intimate partner, and 30 percent of female homicide victims are murdered by one.

A great deal has been written about how victims become paralyzed by abuse—one reason that only about 20 percent of those who have been assaulted, raped, or stalked by an intimate partner obtain a protective order, according to the data available. But the failure of authorities to adequately respond to women like Vernetta Cockerham is also key to explaining why domestic violence remains so deadly. And that is due, in large part, to the fact that many police officers and court officials essentially don't understand the psychological dynamic of abuse, says Evan Stark, PhD, a professor of public health at Rutgers University and author of Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. Police often react to each infraction as an isolated incident, for example, when it is the accumulation of small abusive acts—both physical and emotional—that wears a woman down and emboldens the batterer. Even when a batterer is arrested, Stark says, he rarely spends time in jail, because most assaults are relatively minor: a blackened eye, a bruised arm. (In fact, the most calculating batterers figure out how to manipulate the system to their advantage—filing charges against their spouse, or reporting her to social workers, knowing that the threat of losing her children is more chilling than any beating. And in the presence of authorities, these abusers often appear calm, while the victim is hysterical. Often she ends up being the one blamed.) "Essentially one of the most dramatic forms of oppression in our society is transformed into a second-class misdemeanor," Stark says. "What kind of indignity should women be allowed to suffer before the community takes notice?"

Jessica Lenahan is still trying to make her voice heard. During her marriage to Simon Gonzales, he was never physically violent to her, or to the three girls they were raising in Castle Rock, Colorado. But if the breakfast biscuits were overcooked, he'd hurl them in the trash. If the socks weren't folded the way he liked them, he'd empty the drawers and demand that she redo the laundry. Occasionally, he'd cut off her access to their bank accounts. At one point, he tried to hang himself in the garage, in front of their daughters. The couple separated in 1999, but he continued to terrorize the family by stalking Lenahan and hiding in the closet of the girls' bedroom. On May 21, 1999, Lenahan got a court order that required him to stay 100 yards away.

A month later, on the afternoon of June 22, she discovered her daughters—ages 7, 9, and 10—missing from the front yard. She immediately called the police to alert them that the restraining order was being violated; they told her to wait and see if the kids were returned by 10. It wasn't until 8:30 P.M. that she was finally able to speak to Gonzales on his cell phone. He said he had the girls at an amusement park in Denver, about 30 miles away. Frantic, she called the police again and pleaded with them to find her husband and rescue her children. But they kept telling her to phone back later. Lenahan called the police several more times before going down to the station about 1:00 in the morning to submit an incident report.

At 3:20 A.M., Simon Gonzales drove up to the police station and opened fire with a semiautomatic handgun. The police shot him dead, and when they went to his truck, found the bodies of the three girls in the backseat. "I was so angry," says Lenahan now. "I believed the police would do their job." After the murders, she sued the town of Castle Rock and appealed her case as far as she could, alleging that the police had violated her 14th Amendment right to due process. In 2005 the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case, Castle Rock v. Gonzales, ruling that the arrest laws left room for police discretion and that she had no constitutional right to have her restraining order enforced. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the majority: "We do not believe that these provisions of Colorado law truly made enforcement of restraining orders mandatory. A well-established tradition of police discretion has long coexisted with apparently mandatory arrest statutes."

Many advocates worry that the decision has weakened victim protection, even though it didn't strike down mandatory arrest laws. "The cops I meet around the country say, 'Castle Rock means we don't have to enforce these orders,'" notes Marcus Bruning, supervising deputy with the St. Louis County sheriff's office in Duluth, Minnesota, who trains police nationally to recognize abuse—teaching them, for example, that although it's frustrating when a woman repeatedly returns home to her batterer, that is a sign of his power and control.

Lenahan has gone on to file a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which is part of the Organization of American States, in the hopes of bringing attention to the system's failures. Her struggle fills Vernetta Cockerham with misgivings. "I have an unbelievable fear that my case will end up like Jessica's," Cockerham says.

After the incident in Elkin, Ellerbee was charged with felony assault and violating the emergency protective order; the charges against Cockerham were ultimately dropped. Meanwhile, domestic violence workers had been telling her to take the children to a shelter. But the closest one was in Elkin, in plain view of the road, with no real security or surveillance, and Cockerham felt safer at home with the police station less than 70 yards away. She was also hopeful about her next hearing, scheduled for Tuesday, November 12, at which a judge would rule on extending the emergency protective order. Ellerbee now faced charges in two counties—assault in Surry and communicating threats in Yadkin. She felt confident the judge would revoke his probation and send him to jail, and that safety was just a few days away.

But after spending the weekend before the hearing out of town, she came home to find a large boot print in the fine dust that covered her porch chair—and another one on the railing of the upstairs balcony. Ellerbee had broken in through a window while she was gone. The lock on the file cabinet where she kept her valuables was broken and inside was a note on a torn piece of notebook paper. "I will kill you," it said in Ellerbee's block print. "You will die."

The November 12 hearing was postponed a day while Ellerbee was booked in Surry County on the assault charges and released on a $3,000 bond. The case was supposed to be heard by McLean, the original judge in the July assault case. But, perhaps because of an oversight, a new judge, Jeanie Houston, presided. (The court record is unclear; both McLean and Houston declined to comment.) The assistant district attorney prosecuting Ellerbee was new to the case, too.

Houston found that Ellerbee posed a threat to Cockerham and the children, sufficient evidence to extend the protective order for a year. But the judge did not find that he'd violated his probation, in spite of a recommendation from his probation officer that it be revoked. When Cockerham realized that Ellerbee wasn't going to jail, she became hysterical.

"He's going to take my life," she screamed at the court. "What else can I do?"

Two states away, in Louisville, Kentucky, Jerry J. Bowles, a circuit judge in Jefferson County, runs a very different court—an example of reform efforts being made in various places around the country to improve protection for domestic abuse victims. In Louisville, social workers help judges prepare for cases, and the same judges stay with a case—for years if needed—until it's resolved. Court officials, police, and social workers also meet to review domestic homicides to figure out how the system failed. And a local company developed the nation's first automated system to notify victims when an assailant is released from jail or prison. When it comes to protective orders, Bowles is a strong believer in enforcement—"not only mandatory arrest but sanctions," he says. "I have people serving six months in jail for not completing treatment." As a result, none of the cases that have come before him in the past 13 years has resulted in a murder.

One morning last January, he arrived early for court, wearing cowboy boots under his robes. He took his seat high up on the bench, behind a protective shield of heavy plastic. There were 32 domestic violence cases on the day's docket—mostly women seeking protection. One had been raped by her husband, another beaten, a third stabbed with a corkscrew. A nursing assistant in her 40s sat quietly at the plaintiff's table. The father of her two sons drinks too much, she explained to the judge; she wants out, but he threatens to kill her if she ever leaves. Recently they argued over money, and he pushed her against a chest of drawers.

"It never should have got as far as it did," the man told Bowles. "Yes, I did threaten her. But I'm not a real threat to her. I've got two kids by this lady. I'm not going to do something to hurt my kids."

Bowles issued the protective order. "There's only one reason we threaten people," he told the man sternly. "We want them to think we have the ability to hurt them if they don't do what we want."

After that November 13 hearing, Ellerbee's threats took a darker turn. Cockerham began seeing him in the empty lot across the street from her house with a shovel and wheelbarrow, digging. Then came his voice on her answering machine: "You and the kids will be in those graves and no one will ever know."

Cockerham called Police Chief Coe. He was one of the few who had never dismissed her fears, and she wanted him to hear Ellerbee's words. Coe came to her house, and she showed him the two freshly dug holes just 30 feet from her driveway, one as deep as an adult-sized grave, the second smaller and shallower.

When Coe saw the graves, he says, he put his department of nine officers on alert. According to Coe's deposition, he told Lieutenant Tim Lee Gwyn, "We need to keep a closer watch on what's going on with these people because it could escalate." Still, Ellerbee was not arrested. The protective order gave police the authority to make an arrest without a warrant. Yet because police hadn't actually seen Ellerbee digging the graves, Coe told Cockerham to get a warrant from a magistrate.

Monday morning, November 18, Ellerbee showed up at the Magic Kingdom daycare center, another clear violation of the protective order. Cockerham says she went straight to the police station to report it. Again she was told to obtain an arrest warrant, this time by Scotty Vestal. Cockerham drove 16 miles to the county courthouse and got one.

Later that day, Cockerham stopped Vestal on the street near the station and pointed out Ellerbee's silver Blazer following close behind her. Vestal took off after it in an effort to identify the driver, but Ellerbee eluded him. In his deposition, Vestal said he called Gwyn, who was his supervisor, for help. Gwyn, too, was unable to locate the Blazer. The officers (who are both named in the suit) never turned on their sirens or sent out a general bulletin to law enforcement in the region to find Ellerbee.

As dusk fell late that afternoon, Cockerham says she called the police department and asked Vestal and Gwyn to meet her down the road outside her father's house. She had a copy of the protective order with her and wanted to make sure the officers understood that a violation required them to make an arrest. While the three were talking in the front yard, Ellerbee drove by, slowly, as if taunting them, according to Cockerham, and the two officers got in their cars. She says they told her that they would get him and not to worry. She watched as they followed her husband's Blazer out of sight.

But that conversation—which is central to the lawsuit—is in dispute. Vestal and Gwyn say they met Cockerham there just after the silver Blazer slipped away from them near the police station, not later. They say they never saw Ellerbee drive by the house—and never promised to arrest him.

"Lieutenant Gwyn did tell me that they did see him come by there and that they went after him and couldn't find him," Chief Coe stated in his deposition. The next morning was the day of the murder.

Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

The last memory Cockerham has of Ellerbee is of his hands around her neck.

According to police reports, a neighbor saw him running down the street carrying a paper bag. He went to a convenience store in town and then drove north, headed for New Jersey. On November 22, three days after the murder, he bought a gas can at a Kmart store, filled it at a gas station, walked to a gazebo in Eastside Park in a historic section of Paterson, and set himself on fire.

Two young men saw the smoke and flames. Police found the smoldering body of an unidentified black male.

That was the same day Cockerham left the hospital, where she'd been since the attack, to attend her daughter's funeral, her hands and head still bandaged. Her injuries were so severe that at first the doctors hadn't told her about Candice's death. When the surgeon finally gave her the bad news, he warned her not to scream or cry or do anything that might rupture the sutures in her neck. "There's no words for that," she says. "To lose a child and not be able to cry. You can't scream. You can't holler. You can't yell."

In the hospital, Cockerham was put under police guard, which lasted until Ellerbee's remains were identified through dental records. But even then, Cockerham had a hard time believing her ordeal was over. Any relief she felt turned into anxiety about her boys. She was desperate to see them and hold them close again. But the Yadkin County department of social services had taken them into protective custody. "Their reasoning was if I got into that relationship with Richard, I was subject to getting into another," says Cockerham. "They told me I had my kids in a war zone. I was very offended."

Cockerham hired attorney Loretta Biggs to help get her children back. Biggs, who had just returned to private practice after a year on the North Carolina Court of Appeals, could not fathom why Cockerham's boys hadn't been returned to her. The more Biggs learned about the case, the more she came to believe that the system had seriously betrayed her client. "I think she was perceived as not being worthy of protection, and I just do not understand it," Biggs says.

Once Cockerham regained her footing, she began to get angry. Overwhelmingly angry. After reading up on the law, she filed her suit. While the Supreme Court had ruled in the Castle Rock case that police have discretion to enforce (or not enforce) an order, and that Jessica Lenahan hadn't been entitled to personal protection, Cockerham's case argues that she was entitled to protection, because police had promised it to her. Cockerham's lawyers, Harvey and Harold Kennedy, have won two appeals. In 2006 the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that Cockerham had the right to proceed with the case. Two years later the court ruled that she could also seek punitive damages. Lawyers for the police department have countered that Cockerham is partly responsible for her daughter's death because she did not move to a shelter or take other precautions to protect her. And Cockerham expects attacks against her credibility at the trial.

In preparation for a court date in February, the Kennedys showed her crime scene photos she had never seen, including a blown-up color photograph of her daughter's body bound in gray duct tape. The image left her shaken for days, but she says it has only strengthened her resolve to remain steadfast, and to help other battered women. Working with the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, she recently helped lobby for legislation to bolster the state's arrest laws.

According to police reports, a neighbor saw him running down the street carrying a paper bag. He went to a convenience store in town and then drove north, headed for New Jersey. On November 22, three days after the murder, he bought a gas can at a Kmart store, filled it at a gas station, walked to a gazebo in Eastside Park in a historic section of Paterson, and set himself on fire.

Two young men saw the smoke and flames. Police found the smoldering body of an unidentified black male.

That was the same day Cockerham left the hospital, where she'd been since the attack, to attend her daughter's funeral, her hands and head still bandaged. Her injuries were so severe that at first the doctors hadn't told her about Candice's death. When the surgeon finally gave her the bad news, he warned her not to scream or cry or do anything that might rupture the sutures in her neck. "There's no words for that," she says. "To lose a child and not be able to cry. You can't scream. You can't holler. You can't yell."

In the hospital, Cockerham was put under police guard, which lasted until Ellerbee's remains were identified through dental records. But even then, Cockerham had a hard time believing her ordeal was over. Any relief she felt turned into anxiety about her boys. She was desperate to see them and hold them close again. But the Yadkin County department of social services had taken them into protective custody. "Their reasoning was if I got into that relationship with Richard, I was subject to getting into another," says Cockerham. "They told me I had my kids in a war zone. I was very offended."

Cockerham hired attorney Loretta Biggs to help get her children back. Biggs, who had just returned to private practice after a year on the North Carolina Court of Appeals, could not fathom why Cockerham's boys hadn't been returned to her. The more Biggs learned about the case, the more she came to believe that the system had seriously betrayed her client. "I think she was perceived as not being worthy of protection, and I just do not understand it," Biggs says.

Once Cockerham regained her footing, she began to get angry. Overwhelmingly angry. After reading up on the law, she filed her suit. While the Supreme Court had ruled in the Castle Rock case that police have discretion to enforce (or not enforce) an order, and that Jessica Lenahan hadn't been entitled to personal protection, Cockerham's case argues that she was entitled to protection, because police had promised it to her. Cockerham's lawyers, Harvey and Harold Kennedy, have won two appeals. In 2006 the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that Cockerham had the right to proceed with the case. Two years later the court ruled that she could also seek punitive damages. Lawyers for the police department have countered that Cockerham is partly responsible for her daughter's death because she did not move to a shelter or take other precautions to protect her. And Cockerham expects attacks against her credibility at the trial.

In preparation for a court date in February, the Kennedys showed her crime scene photos she had never seen, including a blown-up color photograph of her daughter's body bound in gray duct tape. The image left her shaken for days, but she says it has only strengthened her resolve to remain steadfast, and to help other battered women. Working with the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, she recently helped lobby for legislation to bolster the state's arrest laws.

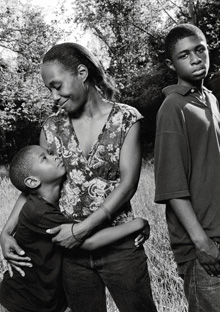

Photo: Mary Ellen Mark

It was raining one day last winter when Cockerham visited her old street. She hasn't lived there since 2005, when she lost the house to foreclosure. The police station has moved to newer quarters, but the library and school are still within sight of the porch where she used to stand and listen for the morning bell to ring as she watched her children walk to class.

Today she and her two boys live in an apartment in Winston-Salem about 40 miles away, depending on social security benefits of about $800 a month. The nightmares that once made her call out in her sleep have mostly subsided. Dominiq, now 7, knows his father and sister are dead but is too young to remember. Rashieq, who just turned 13, has Ellerbee's features—"his face, his walk, his hands; he's the spitting image," Cockerham says. Every time she looks at her beloved son, she realizes she is able to forgive his father a little more.

Candice's ashes rest in the living room, on a rickety bookshelf with the family Bible and a stack of yearbooks. Some days Cockerham drapes one of Candice's favorite knit caps over the wooden urn. It makes her feel as though her daughter is still with her, close by. "I wanted so much for her," she says.

Phoebe Zerwick, a former reporter for the Winston- Salem Journal, is an investigative journalist who lives in North Carolina.

Next: Get the latest update on Vernetta's trial

Abusive men: Spot the red flags

Today she and her two boys live in an apartment in Winston-Salem about 40 miles away, depending on social security benefits of about $800 a month. The nightmares that once made her call out in her sleep have mostly subsided. Dominiq, now 7, knows his father and sister are dead but is too young to remember. Rashieq, who just turned 13, has Ellerbee's features—"his face, his walk, his hands; he's the spitting image," Cockerham says. Every time she looks at her beloved son, she realizes she is able to forgive his father a little more.

Candice's ashes rest in the living room, on a rickety bookshelf with the family Bible and a stack of yearbooks. Some days Cockerham drapes one of Candice's favorite knit caps over the wooden urn. It makes her feel as though her daughter is still with her, close by. "I wanted so much for her," she says.

Phoebe Zerwick, a former reporter for the Winston- Salem Journal, is an investigative journalist who lives in North Carolina.

Next: Get the latest update on Vernetta's trial

Abusive men: Spot the red flags